<I>Buteo Hemilasius</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Around the Region Are Published for Interest Only; Their Inclusion Does Not Imply Acceptance by the Records Committee of the Relevant Country

Sandgrouse31-090402:Sandgrouse 4/2/2009 11:24 AM Page 91 AROUND THE R EGION Dawn Balmer & David Murdoch (compilers) Records in Around the Region are published for interest only; their inclusion does not imply acceptance by the records committee of the relevant country. All records refer to 2008 unless stated otherwise. Records and photographs for Sandgrouse 31 (2) should be sent by 15 June to [email protected] ARMENIA Plover Dromas ardeola at Maharraq on 13 Aug Breeding bird surveys in 2008 in extreme NW was the first for several years. The 2nd record Armenia, near the border with Turkey and of Indian Roller Coracias benghalensis for Georgia (lake Arpilich and adjacent areas, Bahrain was at Badaan farm 5 Oct–15 Nov; the Shirak province), produced 43 new species first record was in Aug 1996 at Dair. The 3rd recorded for the area. Of these, 27 were record of Green Bee- eater Merops orientalis proven to breed there, including Egyptian was at Badaan farm on 29 Nov; the first since Vulture Neophron percnopterus, Booted Eagle several were recorded on the Hawar islands in Aquila pennata, Corncrake Crex crex, Eurasian 2000. Three Dark- throated Thrushes Turdus Eagle Owl Bubo bubo and Barred Warbler atrogularis were found on 20 Dec at Duraiz Sylvia nisoria. Significant breeding range and the 7th record of Chaffinch Fringilla extension for the country also noted here for coelebs was a female that was trapped and Little Bittern Ixobrychus minutus, Blue Rock ringed at Badaan farm on 29 Nov. A House Thrush Monticola solitarius and Meadow Pipit Bunting Emberiza striolata at Badaan farm on Anthus pratensis. -

Gori River Basin Substate BSAP

A BIODIVERSITY LOG AND STRATEGY INPUT DOCUMENT FOR THE GORI RIVER BASIN WESTERN HIMALAYA ECOREGION DISTRICT PITHORAGARH, UTTARANCHAL A SUB-STATE PROCESS UNDER THE NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN INDIA BY FOUNDATION FOR ECOLOGICAL SECURITY MUNSIARI, DISTRICT PITHORAGARH, UTTARANCHAL 2003 SUBMITTED TO THE MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI CONTENTS FOREWORD ............................................................................................................ 4 The authoring institution. ........................................................................................................... 4 The scope. .................................................................................................................................. 5 A DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA ............................................................................... 9 The landscape............................................................................................................................. 9 The People ............................................................................................................................... 10 THE BIODIVERSITY OF THE GORI RIVER BASIN. ................................................ 15 A brief description of the biodiversity values. ......................................................................... 15 Habitat and community representation in flora. .......................................................................... 15 Species richness and life-form -

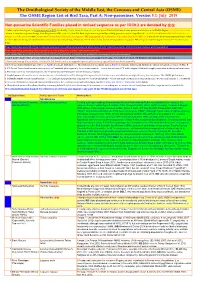

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. -

FACED BUZZARD &Lpar;<I>BUTASTUR INDICUS</I>

j. RaptorRes. 38(3):263-269 ¸ 2004 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. BREEDING BIOLOGY OF THE GREY-FACED BUZZARD (BUTASTUR INDICUS) IN NORTHEASTERN CHINA WEN-HONG DENG 1 MOE KeyLaboratory for BiodiversityScience and Ecological En•neering, College of Life Sciences, BeijingNormal University, Beijing, 100875 China WEI GAO Collegeof Life Sciences,Northeast Normal University, Changchun, 130024 China JI•NG ZHAO Collegeof Life Sciences,illin NormalUniversity, Siping, 136000 China ABSTRACT.--Westudied the breeding biologyof the Grey-facedBuzzard (Butasturindicus) in Zuojia Nature Reserve,Jinlin province,China from 1996-98. Grey-facedBuzzards are summerresidents in northeasternChina. Nesting sites were occupied in Marchand annualreoccupancy was 60%. Grey-faced Buzzardsbuilt new or repairedold nestsin late March and laid eggsin earlyApril. Layingpeaked in late April and spanned32 d (N = 15 clutches).Clutches consisted of 3-4 eggs,incubated for 33 -+ 1 d predominantlyby the female,to whomthe malebrought prey. After young hatched, the femalealso beganhunting. The mean brood-rearingperiod was 38 -+ 2 d and nestlingfemales attained larger asymptoticmass than males,but the lattergrew fasten Males fledged at a meanage of 35 d and females at 39 d. Youngwere slightlyheavier than adultsat fiedging,but the wing chordand tail lengthswere shorterthan thoseof adults.A total of 50 eggswas laid in 15 nests(i clutchsize = 3.3), of which80% hatchedand 90% of the nestlingsfledged. A mean of 2.4 youngfledged per breedingattempt. Overall nest successwas 80%. Causesof nest failure were addled eggsand predation on eggsor nestlingsby small mammals (e.g., Siberian weasel [Mustelasibe•ica] ). KEYWORDS: Grey-facedBuzzard; Butastur indicus; breeding biology; clutch size,, nestlings; fledglings; develop- m•t;, reproductivesuccess. BIOLOG•A REPRODUCTIVA DE BUTASTUR INDICUS EN EL NORESTE DE CHINA REsUMEN.--Estudiamosla biologla reproductiva de Butasturindicus en la reservaNatural de la Provi- denciade Jinlin en Chinadesde 1996-98. -

Influence of Nest Box Design on Occupancy and Breeding Success of Predatory Birds Utilizing Artificial Nests in the Mongolian Steppe

M. L. Rahman, G. Purev-ochir, N. Batbayar & A. Dixon / Conservation Evidence (2016) 13, 21-26 Influence of nest box design on occupancy and breeding success of predatory birds utilizing artificial nests in the Mongolian steppe Md Lutfor Rahman1, Gankhuyag Purev-ochir2, Nyambayar Batbayar2 & Andrew Dixon*1 1International Wildlife Consultants UK Ltd, P.O. Box 19, Carmarthen, SA33 5YL, UK 2 Wildlife Science and Conservation Center, Room 309 Institute of Biology Building, Mongolian Academy of Science, Ulaanbaatar 210351, Mongolia SUMMARY We monitored 100 artificial nests of four different designs to examine the occupancy and breeding success of predatory birds in nest site limited, steppe habitat of central Mongolia. Three species, upland buzzard Buteo hemilasius, common raven Corvus corax and saker falcon Falco cherrug, occupied artificial nests in all years and their number increased over the five-year study period, when the number of breeding predatory birds rose from 0 to 64 pairs in our 324 km2 study area. The number of breeding pairs of saker falcons increased at a faster rate than ravens, reflecting their social dominance. Saker falcons and common ravens preferred to breed inside closed-box artificial nests with a roof, whereas upland buzzards preferred open-top nests. For saker falcons nest survival was higher in closed nests than open nests but there was no significant difference in laying date, clutch size and brood size in relation to nest design. This study demonstrates that whilst nest boxes can increase breeding populations in nest site limited habitats, nest design may also influence occupancy rates and breeding productivity of the species utilizing them. -

Ferruginous Hawk (Buteo Regalis)

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Ferruginous Hawk Buteo regalis in Canada THREATENED 2008 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2008. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Ferruginous Hawk Buteo regalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 24 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: Schmutz, K. J. 1995. COSEWIC update status report on the Ferruginous Hawk Buteo regalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-15 pp. Schmutz, K. J. 1980. COSEWIC status report on the Ferruginous Hawk Buteo regalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-25 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge David A. Kirk and Jennie L. Pearce for writing the update status report on the Ferruginous Hawk, Buteo regalis, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. The report was overseen and edited by Richard Cannings, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee Co- chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la buse rouilleuse (Buteo regalis) au Canada – Mise à jour. Cover illustration: Ferruginous Hawk — Photo by Dr. Gordon Court. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2008. -

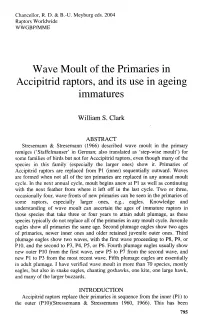

Wave Moult of the Primaries in Accipitrid Raptors, and Its Use in Ageing Immatures

Chancellor, R. D. & B.-U. Meyburg eds. 2004 Raptors Worldwide WWGBP/MME Wave Moult of the Primaries in Accipitrid raptors, and its use in ageing immatures William S. Clark ABSTRACT Stresemann & Stresemann (1966) described wave moult in the primary remiges ('Staffelmauser' in German; also translated as 'step-wise moult') for some families of birds but not for Acccipitrid raptors, even though many of the species in this family (especially the larger ones) show it. Primaries of Accipitrid raptors are replaced from Pl (inner) sequentially outward. Waves are formed when not all of the ten primaries are replaced in any annual moult cycle. In the next annual cycle, moult begins anew at Pl as well as continuing with the next feather from where it left off in the last cycle. Two or three, occasionally four, wave fronts of new primaries can be seen in the primaries of some raptors, especially larger ones, e.g., eagles. Knowledge and understanding of wave moult can ascertain the ages of immature raptors in those species that take three or four years to attain adult plumage, as these species typically do not replace all of the primaries in any moult cycle. Juvenile eagles show all primaries the same age. Second plumage eagles show two ages of primaries, newer inner ones and older retained juvenile outer ones. Third plumage eagles show two waves, with the first wave proceeding to P8, P9, or PIO, and the second to P3, P4, P5, or P6. Fourth plumage eagles usually show new outer PlO from the first wave, new P5 to P7 from the second wave, and new Pl to P3 from the most recent wave. -

North American Buteos with This Charac- Seen by Many Birders but Did Not Return the Next Year

RECOGNIZING HYBRIDS “What is that bird?” How many times have we heard this question or something similar while out birding in a group? The bird in question is often a raptor, shorebird, flycatcher, warbler, or some other hard-to-distinguish bird. Thankfully, there are excellent field guides to help us with these difficult birds, including more- specialized guides for difficult-to-identify families such as raptors, war- blers, gulls, and shore- birds. But when we en- counter hybrids in the field, even the specialty guides are not sufficient. Herein we discuss and present photographs of four individuals that the three of us agree are interspecific hybrids in the genus Buteo. Note: In this article, we follow the age and molt terminology of Howell et al. (2003). Fig. 1. Hybrid Juvenile Hybrid 1 – Juvenile Rough-legged × Swainson’s Hawk Swainson’s × Rough- This hybrid (Figs. 1 & 2) was found by MR, who first noticed it on the legged Hawk. Wing shape morning of 19 November 2002 near Fort Worth, Texas. The hunting hawk is like that of Swainson’s was seen well and rather close up, both in flight and perched. An experi- Hawk, with four notched primaries. But the dark carpal enced birder, MR had never seen a raptor that had this bird’s conflicting patches, the dark belly-band, features: Its wing shape was like that of Swainson’s Hawk, but it had dark the white bases of the tail carpal patches and feathered tarsi, like those of Rough-legged Hawk. MR feathers, and the feathered placed digiscoped photos of this hawk on his web site <www. -

The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Gyps Coprotheres (Aves, Accipitridae, Accipitriformes): Phylogenetic Analysis of Mitogenome Among Raptors

The complete mitochondrial genome of Gyps coprotheres (Aves, Accipitridae, Accipitriformes): phylogenetic analysis of mitogenome among raptors Emmanuel Oluwasegun Adawaren1, Morne Du Plessis2, Essa Suleman3,6, Duodane Kindler3, Almero O. Oosthuizen2, Lillian Mukandiwa4 and Vinny Naidoo5 1 Department of Paraclinical Science/Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa 2 Bioinformatics and Comparative Genomics, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa 3 Molecular Diagnostics, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa 4 Department of Paraclinical Science/Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa 5 Paraclinical Science/Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa 6 Current affiliation: Bioinformatics and Comparative Genomics, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa ABSTRACT Three species of Old World vultures on the Asian peninsula are slowly recovering from the lethal consequences of diclofenac. At present the reason for species sensitivity to diclofenac is unknown. Furthermore, it has since been demonstrated that other Old World vultures like the Cape (Gyps coprotheres; CGV) and griffon (G. fulvus) vultures are also susceptible to diclofenac toxicity. Oddly, the New World Turkey vulture (Cathartes aura) and pied crow (Corvus albus) are not susceptible to diclofenac toxicity. As a result of the latter, we postulate an evolutionary link to toxicity. As a first step in understanding the susceptibility to diclofenac toxicity, we use the CGV as a model species for phylogenetic evaluations, by comparing the relatedness of various raptor Submitted 29 November 2019 species known to be susceptible, non-susceptible and suspected by their relationship Accepted 3 September 2020 to the Cape vulture mitogenome. -

Accipitridae Species Tree

Accipitridae I: Hawks, Kites, Eagles Pearl Kite, Gampsonyx swainsonii ?Scissor-tailed Kite, Chelictinia riocourii Elaninae Black-winged Kite, Elanus caeruleus ?Black-shouldered Kite, Elanus axillaris ?Letter-winged Kite, Elanus scriptus White-tailed Kite, Elanus leucurus African Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides typus ?Madagascan Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides radiatus Gypaetinae Palm-nut Vulture, Gypohierax angolensis Egyptian Vulture, Neophron percnopterus Bearded Vulture / Lammergeier, Gypaetus barbatus Madagascan Serpent-Eagle, Eutriorchis astur Hook-billed Kite, Chondrohierax uncinatus Gray-headed Kite, Leptodon cayanensis ?White-collared Kite, Leptodon forbesi Swallow-tailed Kite, Elanoides forficatus European Honey-Buzzard, Pernis apivorus Perninae Philippine Honey-Buzzard, Pernis steerei Oriental Honey-Buzzard / Crested Honey-Buzzard, Pernis ptilorhynchus Barred Honey-Buzzard, Pernis celebensis Black-breasted Buzzard, Hamirostra melanosternon Square-tailed Kite, Lophoictinia isura Long-tailed Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis longicauda Black Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis infuscatus ?Black Baza, Aviceda leuphotes ?African Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda cuculoides ?Madagascan Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda madagascariensis ?Jerdon’s Baza, Aviceda jerdoni Pacific Baza, Aviceda subcristata Red-headed Vulture, Sarcogyps calvus White-headed Vulture, Trigonoceps occipitalis Cinereous Vulture, Aegypius monachus Lappet-faced Vulture, Torgos tracheliotos Gypinae Hooded Vulture, Necrosyrtes monachus White-backed Vulture, Gyps africanus White-rumped Vulture, Gyps bengalensis Himalayan -

Rough-Legged Buzzard

Correspondence 29 Grimmett, R., Inskipp, C., & Inskipp, T., 2011. Birds of the Indian Subcontinent. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press & Christopher Helm. Pp. 1–528. Prakash, A., 2017. Website URL: https://ebird.org/checklist/S34285650. [Accessed on 19 December 2020.] – Mayur Gawas, Prasanna Kelkar, Jalmesh Karapurkar & Shayeesh Pirankar Mayur Gawas, Goa University, University Road, Taleigao, Goa 403206, India. E-mail: [email protected] Prasanna Kelkar, Bhatwadi, Morlem, Sattari, Goa 403505, India. E-mail: [email protected] Jalmesh Karapurkar, Kothiwada Karapur, Sankhalim, Goa 403505, India. E-mail: [email protected] Shayeesh Pirankar, New Colony Anjunem, Morlem, Sattari, Goa 403505, India. E-mail: [email protected] 49. Rough-legged Buzzard Buteo lagopus from Ladakh, India On Sunday, 03 January 2021 I planned a drive towards Hemis village for birding, and while returning via Stakna village (33.97°N, 77.70°E; c.3,230 m) I saw a raptor on a Poplar Poplus nigera. At first I thought it was just another Common BuzzardButeo buteo (first winter), but after taking some photographs and analyzing them I realized that the bird was different from the Common Buzzard we usually see in Ladakh. That evening, I put the photos [48–52] of the bird on social media and sent some photographs for identification to the person I always ask for help in identifying confusing bird species (Andrew Paul Bailey), and to my surprise, everyone commented it was a Rough-legged Buzzard Buteo lagopus! To satisfy myself further, I referred some books I had, Arlott (2014), and Svensson et al. (2010), and was convinced 50. -

Reproductive Ecology of the Upland Buzzard (Buteo Hemilasius) on the Mongolian Steppe

J. Raptor Res. 44(3):196–201 E 2010 The Raptor Research Foundation, Inc. REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY OF THE UPLAND BUZZARD (BUTEO HEMILASIUS) ON THE MONGOLIAN STEPPE SUNDEV GOMBOBAATAR AND BIRAAZANA ODKHUU National University of Mongolia, Mongolian Ornithological Society, P.O. Box 537, Ulaanbaatar 210646A, Mongolia REUVEN YOSEF1 International Birding and Research Centre in Eilat, P.O. Box 774, 88000 Eilat, Israel BAYANDONOI GANTULGA,PUREVDORJ AMARTUVSHIN, AND DORJ USUKHJARGAL National University of Mongolia, Mongolian Ornithological Society, P.O. Box 537, Ulaanbaatar 210646A, Mongolia ABSTRACT.—The breeding distribution of the Upland Buzzard (Buteo hemilasius) is restricted to the eastern Palearctic. In comparison to other Buteo species, little is known about this species’ breeding ecology. The objectives of our study were to describe nest sites and reproductive success of Upland Buzzards in Mongolia. The average clutch size for 304 breeding attempts in 2001–07 was 3.49 eggs (61.09 SD; range 2–8; total of 1061 eggs laid). For 215 breeding attempts, the average brood size was 1.95 nestlings (61.53; range 0–6). We found that the nest materials and nest size varied greatly, probably corresponding to the availability of nesting materials within the territory. However, the variation in nest size may also reflect the fact that some of the smaller nests were built on human-made structures, such as electric pylons or roofs of small build- ings. KEY WORDS: Upland Buzzard; Buteo hemilasius; Mongolia; reproduction; steppes. ECOLOGI´A REPRODUCTIVA DE BUTEO HEMILASIUS EN LA ESTEPA DE MONGOLIA RESUMEN.—La distribucio´n reproductiva de Buteo hemilasius esta´ restringida al este del Palea´rtico.