Converged Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Årsrapport Innholdsoversikt / NRK 2007

07 Årsrapport INNHOLDSOVERSIKT / NRK 2007 FORORD 3 DRAMA 32 KANALER 62 Om fjernsynsdrama 33 NRK1 63 NYHETER 4 Berlinerpoplene 33 NRK2 64 Ny design og innholdsprofil 5 Utradisjonell seing 34 NRK3 64 Nye NRK2 5 Kodenavn hunter 35 NRK Super 64 Bred valgdekning 6 Størst av alt 36 NRK P1 65 Nyheter på nrk.no 6 Radioteateret 36 NRK P2 66 Nyheter på P1 8 NRK P3 66 Nyheter på P2 8 FAKTA & VITENSKAP 38 Andre kanaler 67 Osenbanden på P3 8 Faktajournalistikk i NRK 39 NRK Sport 67 Internasjonale nyheter 9 Spekter 39 NRK Jazz 67 SKUP-pris til Dagsrevyen 9 Puls — i tre kanaler 40 NRK Båtvær 67 Egenproduksjon 9 Jordmødre 40 NRK Gull 67 yr.no 41 NRK Super 67 BARN 10 Ekstremværuka 42 NRK 5.1 68 Super på tv 11 Radiodokumentaren 43 Alltid Klassisk 68 Superbarn 11 Alltid Nyheter 68 Superstore 12 MINORITETER 44 Alltid Folkemusikk 68 Super på radio 13 10 års jubilant på tv 45 NRK mP3 68 Super på nett 13 Dokumentarer om det flerkulturelle 45 P3 Urørt 68 Spiller.no 13 Norge NRK P1 Oslofjord 68 Melodi Grand Prix Jr 14 Bollywoodsommer 46 NRK Sámi Radio 69 Dokumentar og drama for 14 Kvener 46 NRK1 Tegnspråk 69 barn og unge Musikk 46 NRK Stortinget 69 Ettermiddagstilbud for unge 14 Språklig og kulturelt mangfold i NRK 47 NRK som podkast 69 Nrk.no 69 SPORT 15 LIVSSYN 48 Språkarbeid og nynorskbruk i NRK 70 Vinteridrett 16 Livssyn i faste programmer 49 Teksting av programmer 70 Sportsnyheter 16 Det skjedde i de dager 49 Sportsportalen 16 Salmer til alle tider 49 Ung sport 17 Morgenandakten på P1 49 Fotball på fjernsyn og radio 17 Mellom Himmel og jord 49 Bakrommet -

Arbeidsnotat Nr. 9/05 Utbygging Av Digitalt Bakkenett I Norge

Arbeidsnotat nr. 9/05 Utbygging av digitalt bakkenett i Norge - NRK og TV 2s motiver av Kjersti Lyngtun Hansen Anja Elise Øijordsbakken Husebø SNF prosjekt 1303 ”Konvergens mellom IT, medier og telekommunikasjon: Konkurranse- og mediepolitiske utfordringer” Prosjektet er finansiert av Norges forskningsråd SIØS – Senter for internasjonal økonomi og skipsfart SAMFUNNS- OG NÆRINGSLIVSFORSKNING AS BERGEN, FEBRUAR 2005 ISSN 1503 - 2140 © Dette eksemplar er fremstilt etter avtale med KOPINOR, Stenergate 1, 0050 Oslo. Ytterligere eksemplarfremstilling uten avtale og i strid med åndsverkloven er straffbart og kan medføre erstatningsansvar. SIØS – SENTER FOR INTERNASJONAL ØKONOMI OG SKIPSFART SIØS - Senter for internasjonal økonomi og skipsfart - er et felles senter for Norges Handelshøyskole (NHH) og Samfunns- og næringslivsforskning AS (SNF), med ansvar for undervisning, fri forskning, oppdragsforskning og forskningsformidling innen områdene skipsfartsøkonomi og internasjonal økonomi. Internasjonal økonomi SIØS arbeider med alle typer spørsmål knyttet til internasjonal økonomi og skipsfart, og har særskilt kompetanse på områdene internasjonal realøkonomi (handel, faktorbevegelser, økonomisk integrasjon og næringspolitikk), internasjonal makroøkonomi og internasjonal skattepolitikk. Forskningen ved senteret har i den senere tid vært dominert av prosjekter som har til hensikt å bidra til økt innsikt i globale, strukturelle problemer og virkninger av regional økonomisk integrasjon. Videre deltar man også aktivt i prosjekter som omhandler offentlig -

Cyfrowy Polsat Newsletter 19 – 25 March 2012

Cyyyfrowy Polsat Newsletter 19 – 25 MhMarch 2012 Cyfrowy Polsat Newsletter 19 – 25 March 2012 The press about Cyfrowy Polsat Date The press about TMT market in Poland 19.03 WirtualneMedia.pl: ZenithOptimedia Group: PLN 7.27 billion in advertising spending on the Polish market in 2012 According to the estimates of the ZenithOptimedia Group, the total advertising spending in Poland will be PLN 7.27 billion this year, up 1.9% year‐on‐year. The Internet will benefit the most – the increase will be 15%. The advertising budgets for the radio and cinema channels will rise by 3.7% per annum, while those for the television and outdoor displays will increase by 1.1% and 0.7%, respectively, which will be mainly attributable to Euro 2012. The ZenithOptimedia Group’s overall estima tes of the PlihPolish adtiidvertising markt’ket’svalue in 2012 are based on the positive outlook for Polish GDP, which is widely expected to grow by 2.5‐3.2%. Gazeta Wyborcza: AAAAA Onet for sale at a high price Over the years TVN have persuaded investors that the television and Internet are meant for each other. How will it now explain putting the largest portal in Poland up for sale? Story 1: “it is our intention to lower the debt and focus on our core business”. Story 2: “in fact, we have never been able to combine the portal with the station”. Story 3: “portals are passé”. According to a representative of a large investment bank, “engaging banks to conduct the auction means that there are no queues at Onet’s door. -

Screenforce Tv Halfjaarrapport 2021

SCREENFORCE TV HALFJAARRAPPORT 2021 1 INHOUDSOPGAVE Inleiding 3 3. De TV-kijkers 15 1. De TV-bestedingen 5 TV-schermtijd per categorie 16 Kerncijfers TV-reclame 6 TV-schermtijd per week 17 TV-reclamebestedingen 7 TV-schermtijd per doelgroep 18 Spotbestedingen 8 TV-kijktijd per programmacategorie 19 Non-spotbestedingen 9 Top 25 best bekeken programma’s 20 Verwachting tweede helft 2021 10 Top 25 best bekeken online programma’s 21 2. De TV-adverteerders 11 Bruto TV-bestedingen per week 12 4. Over het TV Halfjaarrapport 22 Bruto TV-bestedingen per branche 13 Begrippenlijst 24 Bruto TV-bestedingen top 25 14 2 INLEIDING 3 INLEIDING RECORDS GEBROKEN IN HET EERSTE HALFJAAR 2021 Het najaar van 2020 liet al positieve signalen zien Signalen over het derde kwartaal zijn eveneens ten tijde van crisis te blijven adverteren. Zij over het herstel van de economie en over het positief. En het CPB heeft alle seinen voor de kunnen met een tevreden gevoel naar onze daaropvolgende herstel van de reclamemarkt. rest van dit jaar en voor 2022 op groen gezet. markt kijken. Hun raad is opgevolgd. Het eerste kwartaal begonnen we niet goed. Screenforce is daarom optimistisch over de Totdat het tweede kwartaal aanbrak en het ontwikkeling van de tweede helft van dit jaar. En de TV-kijkers? Zij werden in de eerste helft herstel van de TV-reclamemarkt zich in een Voor de TV-spotmarkt verwachten we voor het weer op hun wenken bediend. Alle vormen razend tempo ontwikkelde. Het resultaat is een hele jaar uit te komen op een groei van 20-25%. -

Broadcasting Ii Aug 5

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E Broadcasting ii Aug 5 WE'RE PROUD TO BE VOTED THE TWIN CITIES' #1 MUSIC STATION FOR 7 YEARS IN A ROW.* And now, VIKINGS Football! Exciting play -by-play with Joe McConnell and Stu Voigt, plus Bud Grant 4 times a week. Buy a network of 55 stations. Contact Tim Monahan at 612/642 -4141 or Christal Radio for details AIWAYS 95 AND SUNNY.° 'Art:ron 1Y+ Metro Shares 6A/12M, Mon /Sun, 1979-1985 K57P-FM, A SUBSIDIARY OF HUBBARD BROADCASTING. INC. I984 SUhT OGlf ZZ T s S-lnd st-'/AON )IMM 49£21 Z IT 9.c_. I Have a Dream ... Dr. Martin Luther KingJr On January 15, 1986 Dr. King's birthday becomes a National Holiday KING... MONTGOMERY For more information contact: LEGACY OF A DREAM a Fox /Lorber Representative hour) MEMPHIS (Two Hours) (One-half TO Written produced and directed Produced by Ely Landau and Kaplan. First Richard Kaplan. Nominated for MFOXILORBER by Richrd at the Americ Film Festival. Narrated Academy Award. Introduced by by Jones. Harry Belafonte. JamcsEarl "Perhaps the most important film FOX /LORBER Associates, Inc. "This is a powerful film, a stirring documentary ever made" 432 Park Avenue South film. se who view it cannot Philadelphia Bulletin New York, N.Y. 10016 fail to be moved." Film News Telephone: (212) 686 -6777 Presented by The Dr.Martin Luther KingJr.Foundation in association with Richard Kaplan Productions. -

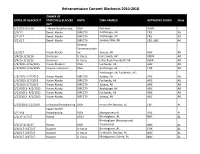

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (Eds.)

From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (eds.) RIPE @ 2007 NORDICOM From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (eds.) NORDICOM From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media RIPE@2007 Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (eds.) © Editorial matters and selections, the editors; articles, individual con- tributors; Nordicom ISBN 978-91-89471-53-5 Published by: Nordicom Göteborg University Box 713 SE 405 30 GÖTEBORG Sweden Cover by: Roger Palmqvist Cover photo by: Arja Lento Printed by: Livréna AB, Kungälv, Sweden, 2007 Environmental certification according to ISO 14001 Contents Preface 7 Jo Bardoel and Gregory Ferrell Lowe From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media. The Core Challenge 9 PSM platforms: POLICY & strategY Karol Jakubowicz Public Service Broadcasting in the 21st Century. What Chance for a New Beginning? 29 Hallvard Moe Commercial Services, Enclosure and Legitimacy. Comparing Contexts and Strategies for PSM Funding and Development 51 Andra Leurdijk Public Service Media Dilemmas and Regulation in a Converging Media Landscape 71 Steven Barnett Can the Public Service Broadcaster Survive? Renewal and Compromise in the New BBC Charter 87 Richard van der Wurff Focus on Audiences. Public Service Media in the Market Place 105 Teemu Palokangas The Public Service Entertainment Mission. From Historic Periphery to Contemporary Core 119 PSM PROGRAMMES: strategY & tacticS Yngvar Kjus Ideals and Complications in Audience Participation for PSM. Open Up or Hold Back? 135 Brian McNair Current Affairs in British Public Service Broadcasting. Challenges and Opportunities 151 Irene Costera Meijer ‘Checking, Snacking and Bodysnatching’. -

Vodafone Invests in New Mobile Phone Generation and TV

Vodafone invests in new mobile phone generation and TV • Nationwide development of LTE becomes new strategic focus • Official launch of hybrid Vodafone TV set-top box Düsseldorf/Berlin, 01. September 2011. Vodafone Germany, with its nationwide de- velopment of and focus on its fourth generation mobile wireless technology LTE (Long Term Evolution), has defined a new strategic focus for the future. The Düsseldorf- based communications company thus meets customer wishes for greater flexibility and individuality. Fritz Joussen, CEO Vodafone Germany: “The future is not bandwidth alone, the future is bandwidth plus mobility. LTE allows society to penetrate the Internet quickly, simply and securely. With this superior technology, we create new opportuni- ties and we pave the way for new communication solutions for the future – in both cities and rural regions throughout Germany.“ Since the work commenced to upgrade the new mobile wireless technology in currently underserved rural areas, Vodafone now reaches around five million households with LTE. Vodafone will shortly be putting the Düsseldorf LTE network into operation. Vodafone is also preparing the new and innova- tive set-top box of Vodafone TV for LTE and is developing it further for the national network. Joussen: “Our customers’ ever greater demand for mobility and the outstanding per- formance of LTE have convinced me to invest in the new mobile wireless technology for private customers. The good old landline times are coming to an end.“ According to the CEO of Vodafone Germany, an outdated landline regulation has prevented the kind of successful competition that you find in the mobile phone market. The regulation, the CEO believes, has prevented competitors of Deutsche Telekom from making significant investments in the fixed network. -

Hystad, Halvdan Ramsdal.Pdf

Sammendrag Denne oppgaven setter søkelys på utbredelsen og bruk av internett over bredbåndstilkoblinger i norske hustander og bedrifter. I oppgaven beskrives ett paradigmeskifte for tradisjonelle formidlingsvirksomheter innen nyhets- og underholdningsmedieformidling. Internett som verktøy viser til å ha endret spillereglene i interaksjonen mellom formidlingsvirksomheter og deres kunder. Mange aktører leter etter nye, effektive og lønnsomme organisasjonsstrukturer for å møte den nye hverdagen. Utviklingstrekkene som synes klare i denne oppgaven er at man går mer og mer i retning av at produksjon og konsumpsjon av innhold i stadig større grad blir digitalisert. Samtidig er en modnet gruppe av internettbruker i ferd med å ta del i å skape sin egen nyhets og underholdningshverdag. Dette har delvis kommet som en årsak av tilgjengeligheten til internett, som er høy, og delvis ved at stadig flere produkter og tjenester orienterer seg mot internett som formidlings- og salgskanal. Oppgaven viser til en rekke eksempler på selskaper, tjenester og applikasjoner som over de siste 5 årene har vert med å prege utviklingsretningen. Videre presenteres noen konsepter og applikasjoner som kan være med å prege den fremtidige utviklingen. Avslutningsvis blir det gitt en skisse over de endringer i organisasjonsstruktur og tilordning til markedene moderne formidlingsvirksomheter i en media 2.0 hverdag kan ta inn over seg og planlegge i sine effektiviserings- og restruktureringsplaner som er aktuelle med hensyn på konjunktursvingninger som skyldes finanskrisen -

Cultura Y Modelo Nórdico Para La Sociedad De La Información

INFORME CULTURA Y MODELO NÓRDICO PARA LA SOCIEDAD DE LA INFORMACIÓN Grupo de investigación 940665 CULTURA Y MODELO NÓRDICO PARA LA SOCIEDAD DE LA INFORMACIÓN Investigadores: Mariano CEBRIÁN Javier MAESTRO Fernando GALLARDO Julio LARRAÑAGA Juan José FERNÁNDEZ Eva LIÉBANA Ángel RUBIO Niels Ole FINNEMANN Helge RÖNNING Kirsti BAGGETHUN INDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 1. Planteamiento y objetivos de la investigación 2. Plan de explotación, difusión y divulgación de los resultados de la investigación CAPITULO 1: DELIMITACIONES SOBRE SOCIEDAD DE LA INFORMACIÓN 1. Concepción de la Sociedad de la Información 1.1. Alcance del sintagma “Sociedad de la Información” 1.2. Complejidad de la Sociedad de la Información 1.2.1. Desarrollo de infraestructuras. Protocolo Internet 1.2.2. De la convergencia de bits a la divergencia de los símbolos 1.2.3. Estructuras organizativas y usuarios 1.2.4. Contexto económico, político, social, cultural y educativo 2. Dimensiones y procesos de globalización 3. La Sociedad de la Información de los países europeos dentro de la globalización 3.1. Creación del dominio .eu 3.2. Fusiones desde la Unión Europea: Nokia-Siemens 4. Perspectiva española CAPÍTULO 2: POLÍTICAS DE I+D EN LOS PAÍSES NÓRDICOS 1. Algunas consideraciones introductorias 2. La política de innovación en la Sociedad de la Información y del Conocimiento 3. Entorno y espíritu empresarial 4. Los objetivos de las políticas de I+D en los Países Nórdicos Dinamarca Finlandia Islandia Noruega Suecia CAPÍTULO 3: REDES, INFRAESTRUCTURAS Y OTRAS DOTACIONES LIGADAS AL DESARROLLO DE LA SOCIEDAD DE LA INFORMACIÓN. (Una comparación de España con los países nórdicos) 1. Redes básicas de telecomunicaciones 1.1. -

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1)

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1) Full Full Full Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation 2 Los Angeles, CA KTLA The CW 57 Mobile, AL WKRG CBS 111 Springfield, MA WWLP NBC 3 Chicago, IL WGN Independent WFNA The CW 112 Lansing, MI WLAJ ABC 4 Philadelphia, PA WPHL MNTV 59 Albany, NY WTEN ABC WLNS CBS 5 Dallas, TX KDAF The CW WXXA FOX 113 Sioux Falls, SD KELO CBS 6 San Francisco, CA KRON MNTV 60 Wilkes Barre, PA WBRE NBC KDLO CBS 7 DC/Hagerstown, WDVM(2) Independent WYOU CBS KPLO CBS MD WDCW The CW 61 Knoxville, TN WATE ABC 114 Tyler-Longview, TX KETK NBC 8 Houston, TX KIAH The CW 62 Little Rock, AR KARK NBC KFXK FOX 12 Tampa, FL WFLA NBC KARZ MNTV 115 Youngstown, OH WYTV ABC WTTA MNTV KLRT FOX WKBN CBS 13 Seattle, WA KCPQ(3) FOX KASN The CW 120 Peoria, IL WMBD CBS KZJO MNTV 63 Dayton, OH WDTN NBC WYZZ FOX 17 Denver, CO KDVR FOX WBDT The CW 123 Lafayette, LA KLFY CBS KWGN The CW 66 Honolulu, HI KHON FOX 125 Bakersfield, CA KGET NBC KFCT FOX KHAW FOX 129 La Crosse, WI WLAX FOX 19 Cleveland, OH WJW FOX KAII FOX WEUX FOX 20 Sacramento, CA KTXL FOX KGMD MNTV 130 Columbus, GA WRBL CBS 22 Portland, OR KOIN CBS KGMV MNTV 132 Amarillo, TX KAMR NBC KRCW The CW KHII MNTV KCIT FOX 23 St. Louis, MO KPLR The CW 67 Green Bay, WI WFRV CBS 138 Rockford, IL WQRF FOX KTVI FOX 68 Des Moines, IA WHO NBC WTVO ABC 25 Indianapolis, IN WTTV CBS 69 Roanoke, VA WFXR FOX 140 Monroe, AR KARD FOX WTTK CBS WWCW The CW WXIN FOX KTVE NBC 72 Wichita, KS -

Drama Directory

2015 UPDATE CONTENTS Acknowlegements ..................................................... 2 Latvia ......................................................................... 124 Introduction ................................................................. 3 Lithuania ................................................................... 127 Luxembourg ............................................................ 133 Austria .......................................................................... 4 Malta .......................................................................... 135 Belgium ...................................................................... 10 Netherlands ............................................................. 137 Bulgaria ....................................................................... 21 Norway ..................................................................... 147 Cyprus ......................................................................... 26 Poland ........................................................................ 153 Czech Republic ......................................................... 31 Portugal ................................................................... 159 Denmark .................................................................... 36 Romania ................................................................... 165 Estonia ........................................................................ 42 Slovakia .................................................................... 174