Ÿ and It One and (7"Je

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Escuela Politécnica Nacional

ESCUELA POLITÉCNICA NACIONAL FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA DE SISTEMAS Propuesta para la Creación del Centro de Investigación Desarrollo e Innovación I+D+I de Tecnologías de la Información de la Escuela Politécnica Nacional TESIS PREVIA A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL GRADO DE MÁSTER (MSc) EN GESTIÓN DE LAS COMUNICACIONES Y TECNOLOGÍA DE LA INFORMACIÓN ING. MERA GUEVARA OMAR FRANCISCO [email protected] ING. PAREDES LUCERO EDGAR SANTIAGO [email protected] DIRECTOR: ING. MONTENEGRO ARMAS CARLOS ESTALESMIT [email protected] Quito, Diciembre 2014 I DECLARACIÓN Nosotros, Omar Francisco Mera Guevara, Edgar Santiago Paredes Lucero, declaramos bajo juramento que el trabajo aquí descrito es de nuestra autoría; que no ha sido previamente presentada para ningún grado o calificación profesional; y, que hemos consultado las referencias bibliográficas que se incluyen en este documento. A través de la presente declaración cedemos nuestros derechos de propiedad intelectual correspondientes a este trabajo, a la Escuela Politécnica Nacional, según lo establecido por la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual, por su Reglamento y por la normatividad institucional vigente. Omar Francisco Mera Edgar Santiago Paredes Guevara Lucero II CERTIFICACIÓN Certifico que el presente trabajo fue desarrollado por Omar Francisco Mera Guevara y Edgar Santiago Paredes Lucero, bajo mi supervisión. Ing. Carlos Montenegro DIRECTOR DE PROYECTO III AGRADECIMIENTOS Con profunda gratitud a mis padres Pancho y Lidi, a mis hijos Dereck y Nayve, a mi esposa Jenny, a mis hermanos Edison y Elizabeth, a mis incondicionales amigos Edgar, Mr Julio Vera; por el apoyo incondicional, confianza, paciencia y dedicación que supieron brindarme durante todo el tiempo que hemos estado juntos, por toda la impronta humana que han dejado para mi vida. -

Spring 2020 Magazine

SPRING 2020 INSIDE TEN YEARS OF COLLECTING • MARK DION • NEW CURATOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY & NEW MEDIA “This brightly colored, monumental piece has something to say—and not just because it’s a play on words. One thing we hope it conveys to students and visitors n is a good-natured ‘Come in! You a m r e k c a are welcome here.’ ” D an Sus Susan Dackerman John & Jill Freidenrich Director of the Cantor Arts Center Yo, Cantor! The museum’s newest large-scale sculpture, in Japanese. “The fact that this particular work Deborah Kass’s OY/YO, speaks in multicultural resonates so beautifully in so many languages to tongues: Oy, as in “oy vey,” is a Yiddish term so many communities is why I wanted to make it of fatigue, resignation, or woe. Yo is a greeting monumental,” artist Kass told the New York Times. associated with American teenagers; it also means “I” in Spanish and is used for emphasis Learn more at museum.stanford.edu/oyyo CONTENTS SPRING 2020 QUICK TOUR 4 News, Acquisitions & Museum Highlights FACULTY PERSPECTIVE 6 Sara Houghteling on Literature and Art CURATORIAL PERSPECTIVE 7 Crossing the Caspian with Alexandria Brown-Hejazi FEATURE 8 Paper Chase: Ten Years of Collecting 3 THINGS TO KNOW 13 About Artist and Alumnus Richard Diebenkorn EXHIBITION GRAPHIC 14 A Cabinet of Cantor Curiosities: PAGE 8 Paper Chase: the Cantor’s major spring exhibition Mark Dion Transforms Two Galleries includes prints from Pakistani-born artist Ambreen Butt, whose work contemplates issues of power and autonomy in the lives of young women. -

The University at a Glance About the University Stanford University

About the University Stanford University n October 1, 1891, the 465 new students who were on Ohand for opening day ceremonies at Leland Stanford Junior University greeted Leland and Jane Stanford enthusi- astically, with a chant they had made up and rehearsed only that morning. Wah-hoo! Wah-hoo! L-S-J-U! Stanford! Its wild and spirited tone symbolized the excitement of this bold adventure. As a pioneer faculty member recalled, “Hope was in every heart, and the presiding spirit of freedom prompted us to dare greatly.” For the Stanford’s on that day, the university was the real- ization of a dream and a fitting tribute to the memory of their only son, who had died of typhoid fever weeks before his sixteenth birthday. Far from the nation’s center of culture and unencumbered by tradition or ivy, the new university Millions of volumes are housed in many libraries throughout the campus. drew students from all over the country: many from California; some who followed professors hired from other colleges and universities; and some simply seeking adventure in the West. Though there were many difficulties during the first months – housing was inadequate, microscopes and books were late in arriving from the East – the first year fore- told greatness. As Jane Stanford wrote in the summer of Stanford University 1892, “Even our fondest hopes have been realized.” The University at a Glance About the University Stanford University Ideas of “Practical Education” Stanford People Governor and Mrs. Stanford had come from families of By any measure, Stanford’s faculty – which numbers modest means and had built their way up through a life of approximately 1,700 – is one of the most distinguished in hard work. -

Stanford University: a World-Class Legacy

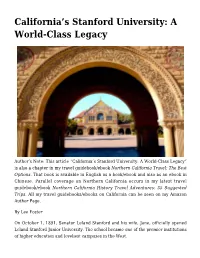

California’s Stanford University: A World-Class Legacy Author’s Note: This article “California’s Stanford University: A World-Class Legacy” is also a chapter in my travel guidebook/ebook Northern California Travel: The Best Options. That book is available in English as a book/ebook and also as an ebookin Chinese. Parallel coverage on Northern California occurs in my latest travel guidebook/ebook Northern California History Travel Adventures: 35 Suggested Trips. All my travel guidebooks/ebooks on California can be seen on myAmazon Author Page. By Lee Foster On October 1, 1891, Senator Leland Stanford and his wife, Jane, officially opened Leland Stanford Junior University. The school became one of the premier institutions of higher education and loveliest campuses in the West. For today’s traveler, headed for the San Francisco region in Northern California, Stanford University is a cultural enrichment to consider including in a trip. The University owes its existence to a tragic death while the Stanford family was on a European Trip in Florence, Italy. After typhoid fever took their only child, a 15- year-old son, the Stanfords decided to turn their 8,200-acre stock farm into the Leland Stanford Junior University. They expressed their desire with the phrase that “the children of California may be our children.” Years later the cerebral establishment is still called by some “The Farm.” Leland Stanford had used the grounds to raise prize trotter racehorses, orchard crops, and wine grapes. The early faculty built homes in Palo Alto, one neighborhood of which became “Professorville.” In a full day of exploration you can visit the campus, adjacent Palo Alto, and the nearby Palo Alto Baylands marshes of San Francisco Bay, a delight to the naturalist. -

2017 Undergraduate Fellows

2017 Undergraduate Fellows More than 400 Stanford students engaged in immersive service opportunities around the world during the summer of 2017. See a map illustrating where all of our Cardinal Quarter participants served. The students listed below are supported by the Haas Center for Public Service’s Undergraduate Fellowships Program. Advancing Gender Equity Fellow The Advancing Gender Equity Fellowship is a joint program with the Women's Community Center and enables students to learn about gender, diversity, and social justice through a summer practicum with a nonprofit organization or government agency addressing social, political, or economic issues affecting women. Jessica Reynoso, '20 (Public Policy); ACT for Women and Girls, Visalia, CA. Jessica worked closely with the Policy Director on several projects such as the Voter Engagement Campaign, which comprised of gathering, collating, and logging signatures for a petition, and phone banking registered voters in the Central Valley. Jessica managed teams who phone-banked, and identified which constituents needed to be followed up with for information regarding contacting their legislators and providing resources. Callan Showers, '19 (American Studies); Gender Justice, St. Paul, MN. As a legal intern at Gender Justice, a nonprofit legal and advocacy organization in St. Paul, Callan worked on everything from deposition summaries and discovery reviews to memos regarding transgender rights in schools and abortion access for women with public health insurance in Minnesota. She got an inside look into the legal field while also fighting for equal rights for people of all gender identities and sexual orientations. Made possible by individual donors to the Haas Center as part of the Cardinal Quarter program. -

Download 2020-2021 Handbook

Stanford Biosciences Student Association Student Handbook 2020-2021 SBSA Executive Board President Jason Rodencal | [email protected] President Candace Liu | [email protected] Vice President Edel McCrea | [email protected] Financial Officer Matine Azadian | [email protected] Communications Brenda Yu | [email protected] CGAP Representative Lucy Xu | [email protected] Website: sbsa.stanford.edu Facebook: facebook.com/SBSAofficial Twitter: twitter.com/SBSA_official Instagram: instagram.com/SBSA_official Contents Welcome! Home Program representation in SBSA Other awesome SBSA activities BioAIMS Li Ka Shing Center for Learning and Knowledge (LKSC) Navigating graduate school Advice for starting graduate students: choosing a lab Advice for starting graduate students: being successful Career Mentoring Stanford opportunities and resources Fellowships Outreach Campus Involvement Professional Development Teaching Writing Sports Useful Stanford websites Offices General Racial Justice Resources Finances Mind over Money National Science Foundation Fellowships Estimated Taxes Banking Emergency Aid and Special Grants Housing Sticker shock Apply for on campus or off campus housing Family housing: what if I have a spouse or partner and/ or children? Deadlines Have roommates Living off-campus: how to find housing Living off-campus: transportation options Statement of support letter from your department Credit score Pets Transportation Transportation at Stanford Getting Around Campus Getting Around the Bay Getting to the Airport Shopping needs Shopping Malls Bed Linens and Housewares Grocery Stores Farmers Markets Electronics Office Supplies Last updated: June 30, 2020 2 | SBSA Handbook 2020-2021 Welcome! The Stanford Biosciences Student Association (SBSA) would like to welcome you to graduate school and to the Stanford community! SBSA is a student-run organization that serves and represents graduate students from biology-related fields in the School of Medicine, the School of Humanities and Sciences, and the School of Engineering. -

The Flowering of Natural History Institutions in California

The Flowering of Natural History Institutions in California Barbara Ertter Reprinted from Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences Volume 55, Supplement I, Article 4, pp. 58-87 Copyright © 2004 by the California Academy of Sciences Reprinted from PCAS 55(Suppl. I:No. 4):58-87. 18 Oct. 2004. PROCEEDINGS OF THE CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Volume 55, Supplement I, No. 4, pp. 58–87, 23 figs. October 18, 2004 The Flowering of Natural History Institutions in California Barbara Ertter University and Jepson Herbaria, University of California Berkeley, California 94720-2465; Email: [email protected] The genesis and early years of a diversity of natural history institutions in California are presented as a single intertwined narrative, focusing on interactions among a selection of key individuals (mostly botanists) who played multiple roles. The California Academy of Sciences was founded in 1853 by a group of gentleman schol- ars, represented by Albert Kellogg. Hans Hermann Behr provided an input of pro- fessional training the following year. The establishment of the California Geological Survey in 1860 provided a further shot in the arm, with Josiah Dwight Whitney, William Henry Brewer, and Henry Nicholas Bolander having active roles in both the Survey and the Academy. When the Survey foundered, Whitney diverted his efforts towards ensuring a place for the Survey collections within the fledgling University of California. The collections became the responsibility of Joseph LeConte, one of the newly recruited faculty. LeConte developed a shared passion for Yosemite Valley with John Muir, who he met through Ezra and Jeanne Carr. Muir also developed a friendship with Kellogg, who became estranged from the Academy following the contentious election of 1887, which was purportedly instigated by Mary Katherine Curran. -

Anna Toledano 450 Jane Stanford Way, Building 200 · Stanford, Ca 94305-2024 · Usa [email protected] · Annatoledano.Com

ANNA TOLEDANO 450 JANE STANFORD WAY, BUILDING 200 · STANFORD, CA 94305-2024 · USA [email protected] · ANNATOLEDANO.COM EDUCATION Ph.D., History of Science, Stanford University expected 2022 • Dissertation: “Collecting Independence: The Science and Politics of Natural History Museums in New Spain, 1770–1820” • Committee: Paula Findlen, Jessica Riskin, Londa Schiebinger, Daniela Bleichmar (USC) M.A., History of Science, Stanford University September 2017 M.A., Museum Anthropology, Columbia University October 2012 A.B. summa cum laude, History of Science, Princeton University May 2011 Certificate in Spanish Language & Culture AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS EXTERNAL Dissertation Completion Award, Mabelle McLeod Lewis Memorial Fund 2020 Alice E. Adams Fellow, The John Carter Brown Library, Brown University Helene W. Koon Memorial Award, Second Prize, Western Society for Eighteenth-Century 2019 Studies Graduate Student Prize, Western History Association San Andreas Fellow and Kenneth E. & Dorothy V. Hill Fellow, The Huntington Library Emerging Scholar Award, International Conference on the Inclusive Museum 2018 Honorable Mention, Graduate Research Fellowship Program, National Science Foundation 2016 UNIVERSITY Digital Humanities Senior Graduate Research Fellow, Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis, 2020 Stanford University Nominee, University Centennial Teaching Prize, Stanford University Digital Humanities Graduate Research Fellow, Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis, Stanford University Lane Research Grant in the History of Science, Medicine, -

Leland Stanford, Jr., Collection SC0033C

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8779n9jf No online items Guide to the Leland Stanford, Jr., Collection SC0033C Processed by Patricia White; machine-readable finding aid created by Patricia White Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2000 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Leland Stanford, Jr., SC0033C 1 Collection SC0033C Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Leland Stanford, Jr., collection creator: Stanford, Leland Identifier/Call Number: SC0033C Physical Description: 2.5 Linear Feet Date (inclusive): 1870-1999 Scope and Content Correspondence, journal, notebooks, drawings, personality studies, and school work of Leland Jr., and condolences to Senator and Mrs. Stanford regarding the death of their son. The correspondence and journal relate primarily to family travels in Europe and activities at home in San Francisco and Palo Alto, to his interests in archeology and collecting, and to his education. The collection also includes correspondence between Jane Lathrop Stanford and William T. Ross, one of Leland Jr.'s tutors. Biography Leland Stanford, Jr., the only child of Senator and Mrs. Leland Stanford, was born in Sacramento, California on May 14, 1868. His early death in March 1884 just before his sixteenth birthday inspired the founding of Leland Stanford Junior University in 1885. Preferred Citation: [Identification of item], Leland Stanford, Jr., Collection (SC0033C). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. -

State of California C the Resources Agency__Primary

State of California The Resources Agency Primary # DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial NRHP Status Code 6Z Other Listings Review Code Reviewer Date Page 1 of 34 *Resource Name or #: (Assigned by recorder) Bonair Siding Corporation Yard P1. Other Identifier: ___ *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County and (P2c, P2e, and P2b or P2d. Attach a Location Map as necessary.) Santa Clara *b. USGS 7.5' Quad Date T ; R ; ; B.M. Palo Alto, CA 1997 6S 3W Rinconada del Arroyo de San Francisquito Mount Diablo c. Address City Zip 315, 319, 321, 327, 333, 340, 341, 357 Bonair Siding Road Stanford 94305 d. UTM: Center: Zone 10S, 574514.06 mE/ 4142781.62 mN; East corner: Zone 10S, 574628.52 mE/ 4142741.46 mN; North corner: Zone 10S, 574489.24 mE/ 442894.16 mN; West corner: Zone 10S,574390.72 mE/ 4142803.91 mN; Southeast corner: Zone 10S,574422.43 mE/ 4142707.33 mN; Southwest corner: Zone 10S,574555.59 mE/ 4142672.30 mN. e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, decimal degrees, etc., as appropriate) *P3a. Description: (Describe resource and its major elements. Include design, materials, condition, alterations, size, setting, and boundaries) This resource consists of the Bonair Siding Corporation Yard, which consists of eight (8) University-owned resources that form part of a corporation yard near the northwest corner of the Stanford University campus. The approximate center of the potential district is located at the west corner of the building addressed 315 Bonair Siding Road (09-100). The potential district is comprised of seven (7) one- and two-story buildings constructed between 1961 and 1982, and one (1) structure constructed in 1992 and altered ca. -

Mrs. Jane Stanford Dies at Moana Hotel

-- --rrr- --- t . fr r f-f- f ' . j HAWAIIAN GAZETTE, FRIDAY. MARCH 3. 1905. SEMI-WEEKL- Y, MRS. JANE STANFORD DIES AT MOANA HOTEL In Honolulu iilnce February 21st. been which could be caused by strychnine ford may be taken back to California one of the reasons she left California. She was accompanied on her arrival poisoning; nnd on the S. S. China, leaving here March She had drunk then from a Left hero by her secretary, MIbh Burner, Second, that strychnine has been 9. They will be urcompanled by Mlsi bottle of Mrs. Highton She , Told Henry and by a maid who Is known as May. In Poland mineral water and became very-ill- found the bicarbonate of soda in Eerner. The burial will take place at I Both women were completely pros ex- the vial from which Miss Bemer Stanford University In the family thuu-soleu- m and. It was alleged that strychnine-hu- trated by the suddenness of last tracted the fatal dose which Mrs. Stan- beside Because of At-- night's tragedy. the bodies of Leland been found In the water. Mls Ber-- San Francisco ford nfterwnrds swallowed. Stanford and son. ner Mrs. Stanford had made numerous How did the strychnine come to be said Mrs. Stanford was conscious edhVca mixed In with the bicarbonate of soda? THE AUTOPSY. to the last moment of her life, and the temot Made There on Her Life. tr Md tXnTcSe" This Is the question which the police The remains were removed yesterday latter had strongly asserted that Bhe V I She was hero In April, 1902, when the department Is attempting to unravel. -

Berton W. Crandall Photographs

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2r29n5sj No online items Preliminary Inventory to the Berton W. Crandall photographs Finding aid prepared by Hoover Institution Archives Staff Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 2001 Preliminary Inventory to the 60022 1 Berton W. Crandall photographs Title: Berton W. Crandall photographs Date: 1888-1953 Collection Number: 60022 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 26 manuscript boxes, 3 card file boxes(12.0 linear feet) Abstract: Depicts Stanford University campus and buildings, Herbert Hoover, Lou Henry Hoover, the Hoover family, Leland Stanford, and Jane Lathrop Stanford. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Crandall, Berton W. Access Boxes 7 and 13-20 restricted. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Berton W. Crandall photographs, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Provenance This collection of photographs was given to the Hoover Institution Archives in 1960 by the photographer himself, Berton W. Crandall, from Palo Alto, California. Introduction The collection consists of two parts. Part 1 mainly documents the life and career of Herbert Hoover and his family, but also includes a few other interesting photographs. Part 2 contains photographs depicting the Stanford campus before the 1906 earthquake and damage resulting from the earthquake, as well as other general photographs. Materials in Part 2 are distinguished from those in part 1 by the "S" preceding each item number.