Foreign Visit Problems of Describing and Interpreting the Development of Land Vegetation Peter D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topic: Soil Classification

Programme: M.Sc.(Environmental Science) Course: Soil Science Semester: IV Code: MSESC4007E04 Topic: Soil Classification Prof. Umesh Kumar Singh Department of Environmental Science School of Earth, Environmental and Biological Sciences Central University of South Bihar, Gaya Note: These materials are only for classroom teaching purpose at Central University of South Bihar. All the data/figures/materials are taken from several research articles/e-books/text books including Wikipedia and other online resources. 1 • Pedology: The origin of the soil , its classification, and its description are examined in pedology (pedon-soil or earth in greek). Pedology is the study of the soil as a natural body and does not focus primarily on the soil’s immediate practical use. A pedologist studies, examines, and classifies soils as they occur in their natural environment. • Edaphology (concerned with the influence of soils on living things, particularly plants ) is the study of soil from the stand point of higher plants. Edaphologist considers the various properties of soil in relation to plant production. • Soil Profile: specific series of layers of soil called soil horizons from soil surface down to the unaltered parent material. 2 • By area Soil – can be small or few hectares. • Smallest representative unit – k.a. Pedon • Polypedon • Bordered by its side by the vertical section of soil …the soil profile. • Soil profile – characterize the pedon. So it defines the soil. • Horizon tell- soil properties- colour, texture, structure, permeability, drainage, bio-activity etc. • 6 groups of horizons k.a. master horizons. O,A,E,B,C &R. 3 Soil Sampling and Mapping Units 4 Typical soil profile 5 O • OM deposits (decomposed, partially decomposed) • Lie above mineral horizon • Histic epipedon (Histos Gr. -

Field Indicators of Hydric Soils

United States Department of Field Indicators of Agriculture Natural Resources Hydric Soils in the Conservation Service United States In cooperation with A Guide for Identifying and Delineating the National Technical Committee for Hydric Soils Hydric Soils, Version 8.2, 2018 Field Indicators of Hydric Soils in the United States A Guide for Identifying and Delineating Hydric Soils Version 8.2, 2018 (Including revisions to versions 8.0 and 8.1) United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, in cooperation with the National Technical Committee for Hydric Soils Edited by L.M. Vasilas, Soil Scientist, NRCS, Washington, DC; G.W. Hurt, Soil Scientist, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL; and J.F. Berkowitz, Soil Scientist, USACE, Vicksburg, MS ii In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. -

World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014 International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps

ISSN 0532-0488 WORLD SOIL RESOURCES REPORTS 106 World reference base for soil resources 2014 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps Update 2015 Cover photographs (left to right): Ekranic Technosol – Austria (©Erika Michéli) Reductaquic Cryosol – Russia (©Maria Gerasimova) Ferralic Nitisol – Australia (©Ben Harms) Pellic Vertisol – Bulgaria (©Erika Michéli) Albic Podzol – Czech Republic (©Erika Michéli) Hypercalcic Kastanozem – Mexico (©Carlos Cruz Gaistardo) Stagnic Luvisol – South Africa (©Márta Fuchs) Copies of FAO publications can be requested from: SALES AND MARKETING GROUP Information Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Viale delle Terme di Caracalla 00100 Rome, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (+39) 06 57053360 Web site: http://www.fao.org WORLD SOIL World reference base RESOURCES REPORTS for soil resources 2014 106 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps Update 2015 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2015 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

The Content of Mineral Nitrogen in Histosols and Its Relationship with Soil Organic Matter

ISSN 1392-3196 Zemdirbyste-Agriculture Vol. 107, No. 1 (2020) 11 ISSN 1392-3196 / e-ISSN 2335-8947 Zemdirbyste-Agriculture, vol. 107, No. 1 (2020), p. 11–16 DOI 10.13080/z-a.2020.107.002 The content of mineral nitrogen in Histosols and its relationship with soil organic matter Gediminas STAUGAITIS, Andrius ŠARKA Lithuanian Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry, Agrochemical Research Laboratory Savanorių 287, Kaunas, Lithuania E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The aim of the research was to investigate the content of mineral nitrogen (Nmin) at the 0–30, 30–60 and 60–90 cm layers of Histosols and their relationship with soil organic matter (SOM). The experiment was conducted in natural or cultivated perennial meadows of Lithuania in 2016–2018. Every year in November, 21 sites were installed and Nmin was analysed. The studies showed that the content of Nmin in Histosols were significantly higher compared to those in mineral soils, and they widely ranged in the air-dried soil samples at different depths as follows: 37.5 to -1 -1 -1 128.2 mg kg at 0–30 cm, 22.9 to 143.4 mg kg at 30–60 cm and 5.2 to 85.3 mg kg at 60–90 cm. Nmin content at the 0–30 and 30–60 cm layers were lower in Bathiterric Histosol and Bathifibric-Fibric Histosol compared to those in Pachiterric Histosol and Pachiterri-Fibric Histosol. In addition, the content of Nmin in Histosols depended on the peat layer thickness. At the 60–90 cm layer of Pachiterric Histosol and Pachiterri-Fibric Histosol, mineral soil was already present in many of the profiles, and SOM was lower, therefore, minN content was lower as well. -

Variability of Soil Types in Wetland Meadows in the South of the Chilean Patagonia

266RESEARCH CHIL. J. AGRIC. RES. - VOL. 70 - Nº 2 - 2010 VARIABILITY OF SOIL TYPES IN WETLAND MEADOWS IN THE SOUTH OF THE CHILEAN PATAGONIA Ladislava Filipová1*, Radim Hédl2, and Nilo Covacevich C.3 ABSTRACT The wetland meadows and pastures (vegas) of the agricultural zone of the Magallanes Region and the Chilean Patagonia are productive and intensively exploited ecosystems. However, there is scarce data about the typology and the physical and chemical properties of the soils that determine the agricultural potential of vegas sites. Sampling of the main horizons of 47 soil profiles was conducted throughout the area. The profiles were described in the field and consequently classified according to the soil typology system of the WRB (IUSS Working Group WRB, 2006). Analyses of bulk and particle densities, capillary water capacity, pH (H2O), pH (CaCl2), texture, organic material, C:N ratio, electrical conductivity, effective cation exchange capacity, N, P, Ca-Mg-K-Na, exchangeable Al, 2- extractable Al, sulfur SO4 , B, and micronutrients (Cu-Zn-Mn-Fe) were carried out. The most frequently recorded groups of soil types in the studied vegas were Histosols - peat soils (20 profiles), and Fluvisols (19). Gleysols (3), Vertisols (1), Regosols (3), Solonchaks (1) and Solonetzs (1) were detected with much less frequency. There is also considerable variability in soil properties among and within the groups of soil types. The principal differences between the Histosols and the Fluvisols are the content of organic matter (often peat), pH level (related to the absence/presence of carbonates) and associated soil properties. Fluvisols are more susceptible to salinization under conditions of aridity, whereas the main threat to Histosols is artificial drainage. -

Global Distribution of Soil Organic Carbon (SOC)

SOIL, 1, 351–365, 2015 www.soil-journal.net/1/351/2015/ doi:10.5194/soil-1-351-2015 SOIL © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Global distribution of soil organic carbon – Part 1: Masses and frequency distributions of SOC stocks for the tropics, permafrost regions, wetlands, and the world M. Köchy1,*, R. Hiederer2, and A. Freibauer1 1Thünen Institute of Climate-Smart Agriculture, Bundesallee 50, 38116 Braunschweig, Germany 2Joint Research Centre, Institute for Environment and Sustainability, Via E. Fermi 2749, 21027 Ispra (VA), Italy *now at: Thünen Institute of Market Analysis, Bundesallee 50, 38116 Braunschweig, Germany Correspondence to: M. Köchy (offi[email protected]) Received: 24 July 2014 – Published in SOIL Discuss.: 3 September 2014 Revised: 27 February 2015 – Accepted: 16 March 2015 – Published: 16 April 2015 Abstract. The global soil organic carbon (SOC) mass is relevant for the carbon cycle budget and thus atmo- spheric carbon concentrations. We review current estimates of SOC stocks and mass (stock × area) in wetlands, permafrost and tropical regions and the world in the upper 1 m of soil. The Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD) v.1.2 provides one of the most recent and coherent global data sets of SOC, giving a total mass of 2476 Pg when using the original values for bulk density. Adjusting the HWSD’s bulk density (BD) of soil high in organic carbon results in a mass of 1230 Pg, and additionally setting the BD of Histosols to 0.1 g cm−3 (typ- ical of peat soils), results in a mass of 1062 Pg. The uncertainty in BD of Histosols alone introduces a range of −56 to C180 Pg C into the estimate of global SOC mass in the top 1 m, larger than estimates of global soil respiration. -

Field Indicators of Hydric Soils in the United States: for All Soils

Field Indicators of Hydric Soils in the United States: For All Soils • From Vasilas, L.M., G.W. Hurt, and C.V. Noble. 2010. Field indicators of hydric soils in the United States (Version 7.0), USDA, NRCS, Fort Worth, TX. http://soils.usda.gov/soil_use /hydric/field_ind.pdf • As revised Field Indicators • The publication Field Indicators of Hydric Soils in the US (Hurt, and Vasilas 2006) is the reference for this lecture. Any statement in this lecture such as “see glossary” refers to this publication. • There are three divisions to the indicators: – Indicators with the letter A preceding a number are used for all soils, regardless of texture. – Indicators with the letter S preceding a number are used for all sandy soil material. – Indicators with the letter F preceding a number are used for all loamy and clayey soil material. Indicators for all soils regardless of texture • All mineral layers above any of the layers meeting an A Indicator(s), except for Indicator A16 have dominant chroma 2 or less, or the layer(s) with dominant chroma of more than 2 is less than 15 cm (6 inches) thick. In addition nodules and concretions are not redox concentrations. Use the following Indicators regardless of texture. A1. Histosol • Histosols (For use in all LRRs) or Histels (For use in LRRs with permafrost). Classifies as a Histosol (except Folist) or as a Histel (except Folistel). • Histosol User Notes: In a Histosol, typically 40 cm (16 inches) or more of the upper 80 cm (32 inches) is organic soil material. Organic soil materials have organic carbon contents (by weight) of 12 to 18 percent, or more, depending on the clay content of the soil. -

Soil Classification Following the US Taxonomy: an Indian Commentary

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/280114947 Soil Classification Following the US Taxonomy: An Indian Commentary ARTICLE · JULY 2015 DOI: 10.2136/sh14-08-0011 DOWNLOADS VIEWS 21 27 1 AUTHOR: Tapas Bhattacharyya International Crops Research Institute for Se… 110 PUBLICATIONS 848 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Tapas Bhattacharyya Retrieved on: 19 August 2015 provided by ICRISAT Open Access Repository View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Published July 17, 2015 Review Soil Classification Following the US Taxonomy: An Indian Commentary T. Bhattacharyya,* P. Chandran, S.K. Ray, and D.K. Pal More than 50 yr ago US soil taxonomy was adopted in India. Since then many researchers have contributed their thoughts to enrich the soil taxonomy. The National Bureau of Soil Survey and Land Use Planning (NBSS & LUP) (Indian Council of Agricultural Research) as a premier soil survey institute has been consistently using benchmark soil series to understand the rationale of the soil taxonomy, keeping in view the soil genesis from different rock systems under various physiographic locations in tropical India. The present review is a humble effort to present this information. ne of the fundamental requirements of any natural science minerals, higher categories of soil classification were conceptu- Ois to classify the proposed bodies or the objects stud- alized (Duchaufour, 1968). The concept of genetic profiles was ied (Joel, 1926). Soils do not exist as discrete objects like plants used in early and current Russian soil classification schemes and animals but occur in nature as a complex and dynamic (Gerasimov, 1975; Gorajichkin et al., 2003). -

Annex: Soil Groups, Characteristics, Distribution and Ecosystem Services

Status of the World’s Main Report Soil Resources Annex Soil groups, characteristics, distribution and ecosystem services © FAO | Giuseppe Bizzarri © FAO INTERGOVERNMENTAL TECHNICAL PANEL ON SOILS Disclaimer and copyright Recommended citation: FAO and ITPS. 2015. Status of the World’s Soil Resources (SWSR) – Main Report. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils, Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-109004-6 © FAO, 2015 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. -

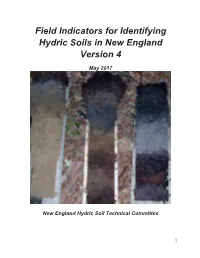

Histosols, Thick Mucky Surface Layers, and Mucky Modified Mineral Layers Should Be Clearly Noted

Field Indicators for Identifying Hydric Soils in New England Version 4 May 2017 New England Hydric Soil Technical Committee 1 The New England Hydric Soils Technical Committee (NEHSTC) consists of the following members: Mark Stolt (Chair), University of Rhode Island Thomas Peragallo (Vice-Chair), LEC Environmental Consultants Inc. James Turenne, (Secretary) USDA – Natural Resources Conservation Service Members: Art Allen, EcoTec, Inc. Al Averill, USDA – Natural Resources Conservation Service Chris Coppi, Albert Frick Associates, Inc. (formerly of Maine DEP) Chris Dorion – Maine Association of Professional Soil Scientists Karen Dudley, USDA – Natural Resources Conservation Service Peter Fletcher, Retired from USDA - Natural Resources Conservation Service James Gove, Gove Environmental Services Greg Granger, USDA – Natural Resources Conservation Service Joseph Homer, Retired, USDA - Natural Resources Conservation Service Gino Infascelli, New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Jacob Isleib, USDA – Natural Resources Conservation Service Ruth Ladd, US Army Corps of Engineers Jim McManus, JMM Wetland Consulting Services LLC Paul Minkin, US Army Corps of Engineers Michael Narcisi, US Army Corps of Engineers Joseph Noel, Private Consultant Donald Parizek, USDA – Natural Resources Conservation Service Maggie Payne, USDA – Natural Resources Conservation Service Jeff Peterson, VHB Sidney Pilgrim, University of New Hampshire (Emeritus) David Rocque, Maine Dept. of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Erica Sachs Lambert, U.S. EPA Matt Schweisberg, Wetland Strategies and Solutions, LLC Michael Sheehan, BlueFlags Ecological Services LLC Mickey Spokas, University of Massachusetts Thomas Villars, USDA – Natural Resources Conservation Service Julie W. Howard, editorial assistance This manual should be cited as follows: New England Hydric Soils Technical Committee. 2017 Version 4, Field Indicators for Identifying Hydric Soils in New England. -

The Soil Orders of Texas

The Soil Orders of Texas The system for classifying soils, Soil Taxonomy, is used worldwide. The highest level of Soil Taxonomy is the Soil Order. There are 12 recognized soil orders in the world. Of these, the state of Texas has 9. There are more than 1,300 soil series in Texas, and each series is classified in one of these 9 soil orders. The Dominant Soil Orders map represents the general distribution of 7 of the 9 soil orders in Texas. The 7 soil orders, Alfisols, Aridisols, Entisols, Inceptisols, Mollisols, Ultisols, and Vertisols, are mapped extensively in the state. The other 2 soil orders, Histosols and Spodosols, which are mapped in the southeastern part of the state, are not shown on the map because they cover relatively small areas. The soil orders not found in Texas are Andisols (volcanic soils), Gelisols (frozen soils), and Oxisols (highly weathered tropical soils). Alfisols Inceptisols The Duval series is an example of an Alfisol. Alfisols have a subsurface The Weswood series is an example of an Inceptisol. Inceptisols are soils with accumulation of clay and have greater than or equal to 35 percent base weakly developed subsurface horizons. These soils may be shallow to saturation. Duval soils occur in the Northern and Western Rio Grande Plain on bedrock, occur on steeply sloping land, or they may be very deep soils in nearly level to gently sloping uplands. areas subject to intermittent flooding. Weswood soils occur along the flood plains of the Brazos and Colorado Rivers in central Texas. Aridisols Mollisols The Upton series is an example of an Aridisol. -

Lecture Notes on the Major Soils of the World

LECTURE NOTES ON THE GEOGRAPHY, FORMATION, PROPERTIES AND USE OF THE MAJOR SOILS OF THE WORLD P.M. Driessen & R. Dudal (Eds) in Q AGRICULTURAL KATHOLIEKE 1 UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITEIT ^.. WAGENINGEN LEUVEN \^ ivr^ - SI I 82 o ) LU- w*y*'tinge n ökSjuiOTHEEK ÎCANDBOUWUNWERSIIEI^ WAGENINGEN TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE INTRODUCTION The FAO-Unesco classificationo f soils 3 Diagnostichorizon s anddiagnosti cpropertie s 7 Key toMajo r SoilGrouping s 11 Correlation 14 SET 1. ORGANIC SOILS Major SoilGrouping :HISTOSOL S 19 SET 2. MINERAL SOILS CONDITIONED BYHUMA N INFLUENCES Major SoilGrouping :ANTHROSOL S 35 SET 3. MINERAL SOILS CONDITIONED BYTH E PARENT MATERIAL Major landforms involcani c regions 43 Major SoilGrouping :ANDOSOL S 47 Major landforms inregion swit h sands 55 Major SoilGrouping :ARENOSOL S 59 Major landforms insmectit eregion s 65 Major SoilGrouping :VERTISOL S 67 SET 4. MINERAL SOILS CONDITIONED BYTH E TOPOGRAPHY/PHYSIOGRAPHY Major landforms inalluvia l lowlands 83 Major SoilGroupings :FLUVISOL S 93 (with specialreferenc e toThioni c Soils) GLEYSOLS 105 Major landforms inerodin gupland s 111 Major SoilGroupings :LEPTOSOL S 115 REGOSOLS 119 SET 5. MINERAL SOILS CONDITIONED BYTHEI RLIMITE D AGE Major SoilGrouping : CAMBISOLS 125 SET 6. MINERAL SOILS CONDITIONED BYA WE T (SUB)TROPICAL CLIMATE Major landforrasi ntropica l regions 133 Major SoilGroupings :PLINTHOSOL S 139 FERRALSOLS 147 NITISOLS 157 ACRISOLS 161 ALISOLS 167 LIXISOLS 171 SET 7. MINERAL SOILS CONDITIONED BYA (SEMI-)AR-ID CLIMATE Major landforms inari d regions 177 Major SoilGroupings :SOLONCHAK S 181 SOLONETZ 191 GYPSISOLS 197 CALCISOLS 203 SET 8. MINERAL SOILS CONDITIONED BYA STEPPIC CLIMATE Major landforms instepp e regions 211 Major Soil Groupings:KASTANOZEM S 215 CHERNOZEMS 219 PHAEOZEMS 227 GREYZEMS 231 SET 9.