Harrow in the Roman Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bentley Priory Museum

CASE STUDY CUSTOMER BENTLEY PRIORY MUSEUM Museum streamlines About Bentley Priory Bentley Priory is an eighteenth to with VenposCloud nineteenth century stately home and deer park in Stanmore on the northern edge of the Greater TheTHE Challenge: CHALLENGE London area in the London Bentley Priory Museum is an independent museum and registered charity based in Borough of Harrow. North West London within an historic mansion house and tells the important story of It was originally a medieval priory how the Battle of Britain was won. It is open four days a week with staff working or cell of Augustinian Canons in alongside a team of more than 90 volunteers. It offers a museum shop and café and Harrow Weald, then in Middlesex. attracts more than 8,000 visitors a year including school and group visits. With visitor numbers rising year on year since it opened in 2013, a ticketing and membership In the Second World War, Bentley system which could cope with Gift Aid donations and which ensured a smooth Priory was the headquarters of RAF Fighter Command, and it customer journey became essential. remained in RAF hands in various TheTHE Solution: SOLUTION roles until 2008. The Trustees at Bentley Priory Museum recognized that the existing till system no Bentley Priory Museum tells the longer met the needs of the museum. It was not able to process Gift Aid donations fascinating story of the beautiful while membership applications were carried out on paper and then processed by Grade II* listed country house, volunteers where time allowed. Vennersys was able to offer a completely new focusing on its role as integrated admissions, membership, reporting and online booking system for events Headquarters Fighter Command for Bentley Priory Museum. -

Harrow Natural History Society 50Th Anniversary

HARROW NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY 50TH ANNIVERSARY Miss Pollard who was the chief Librarian in Harrow founded the Harrow Natural History Society in 1970. The first venue for indoor meetings was Wealdstone Library in Grant Road. The Society studied two main areas – Harrow Weald Common and Bentley Priory Open Space. Nature Trails were laid out on both these sites and records of the wild life collected. Miss Pollard retired and left the area in December 1973, she had been Chairman of the Society. Alan Tinsey took over this role when she left. He had already produced the first journal using the knowledge of members many of whom were very familiar with the district. He went on to produce four more journals but by this time articles were getting hard to find and it was decided to produce a newsletter telling members about the work of the Society which would be sent out to members with their programmes. This newsletter was compiled by a separate committee and it continued afterwards. Alan and Geoff Corney who had been Secretary since the beginning, both retired at the AGM in 1979. Geoff had been very active in the work of the Society and felt he needed a rest. George Alexander became the new Chairman and Kevin Reidy became the new Secretary. Two further publications were under discussion about the local wild flowers and birds. Jack Phillips a very knowledgeable botanist suggested the Society should produce a simple guide to the wild flowers. Merle Marsden undertook to do this. She collected a small group of helpers and produced the first flower book. -

(Hard Court) Football Pitch Green Gym Childrens Playground

Tennis Basketball Basketball Cricket Football Green Childrens Parks and Open Spaces Type of Space Description Public Transport Links Car Park (Hard Hoop Court Pitch Pitch Gym Playground Court) Alexandra Park is located in South Harrow and has 3 entrances National Rail, Piccadilly ALEXANDRA PARK on Alexandra Avenue, Park Lane and Northolt Road. The Park Medium Park Line and Multiple Bus No Yes No No No No Yes Yes Alexandra Avenue, South Harrow covers a massive 21 acres of green space and has a basketball Routes court, a green gym and small parking facilities Byron Recreation Ground is located in Wealdstone and is home National Rail, to Harrow's best Skate Park. It has entrances from Christchurch Metropolitan Line, Yes BYRON REC Yes Yes Large Park Avenue, Belmont Road and Peel Road. Car parking is available London Overground, (Est. 350 Yes No No Yes Yes Peel Road, Wealdstone (x3) (x3) in a Pay and Display car park adjacent to the park Christchurch Bakerloo Line and Spaces) Avenue Multiple Bus Routes Canons Park is part of an eighteenth century parkland and host Jubilee Line, Northern CANONS PARK to the listed George V Memorial garden, which offers a tranquil Large Park Line and Multiple Bus No Yes No No No No Yes Yes Donnefield Avenue, Edgware enclosed area. Entrances are from Canons Drive, Whitchurch Routes Lane, Howberry Road and Cheyneys Avenue Centenary Park has some of best outdoor sports facilities in Harrow which include; 4 tennis courts, a 3G 5-a-side football CENTENARY PARK Jubilee Line and Yes Medium Park pitch and a 9 hole pitch and putt golf course. -

Job 113917 Type

ELEGANT GEORGIAN STYLE DUPLEX APARTMENT SET IN 57 ACRES OF PARKLAND. 11 Bentley Priory, Mansion House Drive, Stanmore, Middlesex HA7 3FB Price on Application Leasehold Elegant Georgian style duplex apartment set in 57 acres of parkland. 11 Bentley Priory, Mansion House Drive, Stanmore, Middlesex HA7 3FB Price on Application Leasehold Sitting room ◆ kitchen/dining room ◆ 3 bedrooms ◆ 2 bath/ shower rooms ◆ entrance hall ◆ cloakroom ◆ 2 undercroft parking spaces ◆ gated entrance ◆ 57 acres of communal grounds ◆ No upper chain ◆ EPC rating = C Situation Bentley Priory is a highly sought after location positioned between Bushey Heath & Stanmore, with excellent local shopping facilities. There are convenient links to Central London via Bushey Mainline Silverlink station (Euston 25 minutes) and the Jubilee Line from Stanmore station connects directly to the West End and Canary Wharf. Junction 5 M1 and Junction 19 M25 provide excellent connections to London, Heathrow and the UK motorway network. The Intu shopping centre at Watford is about 2.4 miles away. Local schooling both state and private are well recommended and include Haberdashers' Aske's, North London Collegiate and St Margaret’s. Description An exceptional Georgian style, south and west facing duplex apartment situated in an exclusive development set within 57 acres of stunning parkland and gardens at Bentley Priory, providing a unique and tranquil setting only 12 miles from Central London. The property also benefits from the security and convenience of a 24 hour concierge service and gated entrance with Lodge. Bentley Priory has a wealth of history having previously been the home of the Dowager Queen Adelaide and R.A.F. -

Area Plan Proposal for London Has Been Developed and in This Booklet You Will Find Information on the Changes Proposed for London

Post Office Ltd Network Change Programme Area Plan Proposal London 2 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Proposed Local Area Plan 3. The Role of Postwatch 4. List of Post Office® branches proposed for closure 5. List of Post Office® branches proposed to remain in the Network • Frequently Asked Questions Leaflet • Map of the Local Area Plan • Branch Access Reports - information on proposed closing branches and details of alternative branches in the Area 3 4 1. Introduction The Government has recognised that fewer people are using Post Office® branches, partly because traditional services, including benefit payments and other services are now available in other ways, such as online or directly through banks. It has concluded that the overall size and shape of the network of Post Office® branches (“the Network”) needs to change. In May 2007, following a national public consultation, the Government announced a range of proposed measures to modernise and reshape the Network and put it on a more stable footing for the future. A copy of the Government’s response to the national public consultation (“the Response Document”) can be obtained at www.dti.gov.uk/consultations/page36024.html. Post Office Ltd has now put in place a Network Change Programme (“the Programme”) to implement the measures proposed by the Government. The Programme will involve the compulsory compensated closure of up to 2,500 Post Office® branches (out of a current Network of 14,300 branches), with the introduction of about 500 service points known as “Outreaches” to mitigate the impact of the proposed closures. Compensation will be paid to those subpostmasters whose branches are compulsorily closed under the Programme. -

Harrow Street Spaces Plan – Initial Programme of Works

HARROW STREET SPACES PLAN – INITIAL PROGRAMME OF WORKS Pedestrian space (PS) Locations have been identified where there is usually higher pedestrian footfall in footway areas with restricted space, 3 metres or less in width. This is mainly at shopping parades and some bus stops and stations where the restricted width will make social distancing requirements difficult to adhere to. The measures will reallocate road space to pedestrians and would be temporary for as long as social distancing is required. Ref. Scheme Description Station Road (near Civic Centre) – Suspend parking bays and introduce PS-01 shops and mosque widened pedestrian space The Bridge - Harrow and Remove single traffic lane and introduce PS-02 Wealdstone Station widened pedestrian space The Broadway, Hatch End - service Suspend parking bays on one side and PS-03 roads introduce widened pedestrian space Stanmore Broadway – service Suspend parking bays on one side and PS-04 roads introduce widened pedestrian space Various traffic signals pedestrian Set minimum call time on pedestrian PS-05 phases – borough wide signals to reduce wait time Implement planned major scheme ready Wealdstone Town Centre PS-06 for implementation - pedestrian, cycling, improvement scheme transport hub and bus interventions Streatfield Road, Queensbury Suspend parking on one side and PS-07 (Honeypot Lane & Charlton Road) introduce widened pedestrian space service roads Honeypot Lane service road (near Suspend parking on one side and PS-08 Wemborough Road) introduce widened pedestrian space Northolt -

New Electoral Arrangements for Harrow Council Final Recommendations May 2019 Translations and Other Formats

New electoral arrangements for Harrow Council Final recommendations May 2019 Translations and other formats: To get this report in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England at: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] Licensing: The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2019 A note on our mapping: The maps shown in this report are for illustrative purposes only. Whilst best efforts have been made by our staff to ensure that the maps included in this report are representative of the boundaries described by the text, there may be slight variations between these maps and the large PDF map that accompanies this report, or the digital mapping supplied on our consultation portal. This is due to the way in which the final mapped products are produced. The reader should therefore refer to either the large PDF supplied with this report or the digital mapping for the true likeness of the boundaries intended. The boundaries as shown on either the large PDF map or the digital mapping should always appear identical. Contents Introduction 1 Who we are and what we do 1 What is an electoral review? 1 Why Harrow? 2 Our proposals for Harrow 2 How will the recommendations affect you? 2 Review timetable 3 Analysis and final recommendations -

Bentley Priory Circular Walk

, Stanmore , ay W Lodge Old 5. arren Lane arren W on park car Common Stanmore 4. 3. Priory Drive stop on 142 bus 142 on stop Drive Priory 3. details. 2. Priory Close stop on 258 bus 258 on stop Close Priory 2. deer - see text for for text see - deer pub missing the tame tame the missing August 2016 August Forum Conservation Nature Altered Altered is Case The of west just park, car Redding Old 1. licence way means means way , Creative Commons Commons Creative , Geezer Diamond by Image Leaflet revised and redesigned by Harrow Harrow by redesigned and revised Leaflet but going this this going but Altered. is Case The at the corresponding pink circle pink corresponding the at Stanmore Hill, Hill, Stanmore by pink circles on the maps. For each, start reading the text text the reading start each, For maps. the on circles pink by newsagents on on newsagents There are five good starting points for the walk, indicated indicated walk, the for points starting good five are There available at a a at available confectionery are are confectionery (LOOP), a 150 mile route encircling London. encircling route mile 150 a (LOOP), and and Parts of the route follow the London Outer Orbital Path Path Orbital Outer London the follow route the of Parts Canned drinks drinks Canned on the maps. maps. the on . badly stomachs their upset close to point 1 1 point to close The deer must not be fed bread which will will which bread fed be not must deer The along. suitable on the route, route, the on , take something something take , party the in children have you if especially Altered pub lies lies pub Altered love vegetables (especially carrots) and apples - so so - apples and carrots) (especially vegetables love The Case is is Case The ou will pass a private deer park with tame fallow deer that that deer fallow tame with park deer private a pass will ou Y eshments Refr wildflowers that make this area so attractive. -

Circle and Hammersmith & City Lines Timetable Alterations

Timetable Notice No. 51/16 Page 1 of 2 CIRCLE AND HAMMERSMITH & CITY LINES TIMETABLE ALTERATIONS DUE TO METROPOLITAN LINE ENGINEERING WORK MONDAY TO WEDNESDAY NIGHTS AND TUESDAY TO THURSDAY MORNINGS, COMMENCING 16th MAY 2016 AND UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE In connection with Metropolitan Line track and drainage renewal work between Baker Street and Finchley Road on Monday to Wednesday nights and Tuesday to Thursday mornings, commencing 16th May, the arrangements shown in this Timetable Notice will apply. The Metropolitan Line train service will be suspended between Wembley Park and Aldgate from approximately 21.55 (southbound from Wembley Park) and 22.50 (northbound from Baker Street) on Monday to Wednesday nights until approximately 05.30 (southbound at Wembley Park) and 05.55 (northbound at Baker Street) on Tuesday to Thursday mornings. In consequence, the two late evening Circle and Hammersmith & City Line trains which stable at Neasden Depot/Wembley Park Sidings will be diverted to stable at Hammersmith Depot. To balance the rolling stock, two S7 trains will transfer empty from Hammersmith Depot to Neasden Depot/Wembley Park Sidings before the Metropolitan Line closure begins. Circle and Hammersmith & City Line trains will be amended as follows:- Monday to Wednesday nights Train H706, will start from Hammersmith Depot at 21.13 and run (additional empty throughout) as follows:- Hammersmith (24 road) arrive 21.16, form 21.24, Goldhawk Road 21/25½, Latimer Road 21/30, Paddington (Suburban) 21/36½, Praed Street Junction 21/39, Edgware Road (platform 1) 21/40½, Baker Street 21a43½, King’s Cross 21/49, Farringdon 21/52½, Moorgate (platform 3) arrive 21.57½, form 22.10½, Farringdon 22/13½, King’s Cross 22/17, Baker Street (platform 2) 22a23½, Finchley Road 22/29, Neasden 22/33½, Wembley Park (platform 1) 22/35½, FL, Harrow-on-the-Hill (platform 4) 22.41½, reverse via siding, form 22.51½ via Harrow-on-the-Hill (platform 5), FL, Wembley Park (platform 6) 23m02, Neasden Depot (N) arrive 23.11 and stable. -

Standard-Tube-Map.Pdf

Tube map 123456789 Special fares apply Special fares Check before you travel 978868 7 57Cheshunt Epping apply § Custom House for ExCeL Chesham Watford Junction 9 Station closed until late December 2017. Chalfont & Enfield Town Theydon Bois Latimer Theobalds Grove --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Watford High Street Bush Hill Debden Shenfield § Watford Hounslow West Amersham Cockfosters Park Turkey Street High Barnet Loughton 6 Step-free access for manual wheelchairs only. A Chorleywood Bushey A --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Croxley Totteridge & Whetstone Oakwood Southbury Chingford Buckhurst Hill § Lancaster Gate Rickmansworth Brentwood Carpenders Park Woodside Park Southgate 5 Station closed until August 2017. Edmonton Green Moor Park Roding Grange Valley --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Hatch End Mill Hill East West Finchley Arnos Grove Hill Northwood Silver Street Highams Park § Victoria 4 Harold Wood Chigwell West Ruislip Headstone Lane Edgware Bounds Green Step-free access is via the Cardinal Place White Hart Lane Northwood Hills Stanmore Hainault Gidea Park Finchley Central Woodford entrance. Hillingdon Ruislip Harrow & Wood Green Pinner Wealdstone Burnt Oak Bruce Grove Ruislip Manor Harringay Wood Street Fairlop Romford --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Canons Park Green South Woodford East Finchley Uxbridge Ickenham North Harrow Colindale Turnpike Lane Lanes -

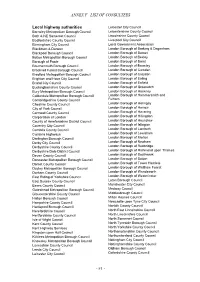

Annex F –List of Consultees

ANNEX F –LIST OF CONSULTEES Local highway authorities Leicester City Council Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Leicestershire County Council Bath & NE Somerset Council Lincolnshire County Council Bedfordshire County Council Liverpool City Council Birmingham City Council Local Government Association Blackburn & Darwen London Borough of Barking & Dagenham Blackpool Borough Council London Borough of Barnet Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Bexley Borough of Poole London Borough of Brent Bournemouth Borough Council London Borough of Bromley Bracknell Forest Borough Council London Borough of Camden Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Croydon Brighton and Hove City Council London Borough of Ealing Bristol City Council London Borough of Enfield Buckinghamshire County Council London Borough of Greenwich Bury Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hackney Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hammersmith and Cambridgeshire County Council Fulham Cheshire County Council London Borough of Haringey City of York Council London Borough of Harrow Cornwall County Council London Borough of Havering Corporation of London London Borough of Hillingdon County of Herefordshire District Council London Borough of Hounslow Coventry City Council London Borough of Islington Cumbria County Council London Borough of Lambeth Cumbria Highways London Borough of Lewisham Darlington Borough Council London Borough of Merton Derby City Council London Borough of Newham Derbyshire County Council London -

Archaeological Desk Based Assessment

Archaeological Desk Based Assessment __________ Brockley Hill, Stanmore - New Banqueting Facility, Brockley Hill, London Borough of Harrow Brockley Hill DBA Update | 1 June 2020 | Project Ref 6129A Project Number: 06129A File Origin: P:\HC\Projects\Projects 6001-6500\6101 - 6200\06129 - Former Stanmore and Edgware Golf Club, Brockley Hill\AC\Reports\2020.08.25 - Brockley Hill DBAv3.docx Author with date Reviewer code, with date AJ, 25.02.2020 RD-0023, 25.02.2020 JM-0057,13.08.202019 JM, 25.08.2020 HGH Consulting, 15.08.2020 Brockley Hill DBA Update | 2 Contents Non-Technical Summary 1. Introduction ........................................................................................ 6 2. Methodology ...................................................................................... 13 3. Relevant Policy Framework ............................................................... 16 4. Archaeological Background ............................................................... 21 5. Proposed Development, Assessment of Significance and Potential Effects ............................................................................................... 37 6. Conclusions ....................................................................................... 41 7. Sources Consulted ............................................................................. 43 8. Figures .............................................................................................. 46 Appendices Appendix 1: Greater London Historic Environment Record Data Figures