THE ECOLOGY and INFLUENCE of LAND USE on RIVER TURTLES in SOUTHWEST GEORGIA by SEAN CHRISTOPHER STERRETT (Under the Direction Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contamination Status of Polychlorinated Biphenyls

ACCUMULATION OF POLYCHLORINED BIPHENYLS IN FISH COLLECTED FROM ST. SIMONS ESTUARY, BRUNSWICK, GEORGIA, USA Hao L1, Senthil Kumar K1, Sajwan K S1, Li P1, Peck A2, Gilligan M1, Pride C1 1 Department of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Savannah State University, 3219 College Street, Savannah, GA 2 31404, USA; Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, #10 Ocean Science Circle, Savannah, GA 31411, USA Abstract Contamination profiles of 17 PCB congeners were determined in five fish species collected at eight sites in St. Simons Estuary, Brunswick, Georgia, USA (which is very close to an LCP Superfund Site). Pinfish collected at Turtle River at Buffalo Swamp had the highest PCBs concentration (143 ng/g wet weight [ww]). Whiting and southern flounder collected at Turtle River at Buffalo Swamp also had higher PCBs concentrations (57 ng/g and 73 ng/g ww, respectively) than the same fish species collected at the other sites (the Mouth of Frederica River, Back River, Mackay River South of Jove Creek, Towers of St Simons, Lower Jekyll Cove, Turtle River at Andrew Island, and Turtle River at Cowpen Creek). The current PCBs concentrations of fish in our study were lower than those reported in previous studies. Introduction Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are classified as persistent organic pollutants (POPs), which are toxic to humans and wildlife1. PCBs are ubiquitous chemicals including in marine ecosystems, and posed potential harm to all kinds of living things2-3. St. Simons Estuary is located in Brunswick, Glynn County, Georgia. Brunswick has a poor record of environmental protection due to the negative impact of chemical pollution from Linden Chemicals and Plastics (LCP) Superfund Site. -

EMYDIDAE P Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles

REPTILIA: TESTUDINES: EMYDIDAE P Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Pseudemysj7oridana: Baur, 1893:223 (part). Pseudemys texana: Brimley, 1907:77 (part). Seidel, M.E. and M.J. Dreslik. 1996. Pseudemys concinna. Chrysemysfloridana: Di tmars, 1907:37 (part). Chrysemys texana: Hurter and Strecker, 1909:21 (part). Pseudemys concinna (LeConte) Pseudemys vioscana Brimley, 1928:66. Type-locality, "Lake River Cooter Des Allemands [St. John the Baptist Parrish], La." Holo- type, National Museum of Natural History (USNM) 79632, Testudo concinna Le Conte, 1830: 106. Type-locality, "... rivers dry adult male collected April 1927 by Percy Viosca Jr. of Georgia and Carolina, where the beds are rocky," not (examined by authors). "below Augusta on the Savannah, or Columbia on the Pseudemys elonae Brimley, 1928:67. Type-locality, "... pond Congaree," restricted to "vicinity of Columbia, South Caro- in Guilford County, North Carolina, not far from Elon lina" by Schmidt (1953: 101). Holotype, undesignated, see College, in the Cape Fear drainage ..." Holotype, USNM Comment. 79631, dry adult male collected October 1927 by D.W. Tesrudofloridana Le Conte, 1830: 100 (part). Type-locality, "... Rumbold and F.J. Hall (examined by authors). St. John's river of East Florida ..." Holotype, undesignated, see Comment. Emys (Tesrudo) concinna: Bonaparte, 1831 :355. Terrapene concinna: Bonaparte, 183 1 :370. Emys annulifera Gray, 183 1:32. Qpe-locality, not given, des- ignated as "Columbia [Richland County], South Carolina" by Schmidt (1953: 101). Holotype, undesignated, but Boulenger (1889:84) listed the probable type as a young preserved specimen in the British Museum of Natural His- tory (BMNH) from "North America." Clemmys concinna: Fitzinger, 1835: 124. -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

Guidelines for Eating Fish from Georgia Waters 2017

Guidelines For Eating Fish From Georgia Waters 2017 Georgia Department of Natural Resources 2 Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, S.E., Suite 1252 Atlanta, Georgia 30334-9000 i ii For more information on fish consumption in Georgia, contact the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Environmental Protection Division Watershed Protection Branch 2 Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, S.E., Suite 1152 Atlanta, GA 30334-9000 (404) 463-1511 Wildlife Resources Division 2070 U.S. Hwy. 278, S.E. Social Circle, GA 30025 (770) 918-6406 Coastal Resources Division One Conservation Way Brunswick, Ga. 31520 (912) 264-7218 Check the DNR Web Site at: http://www.gadnr.org For this booklet: Go to Environmental Protection Division at www.gaepd.org, choose publications, then fish consumption guidelines. For the current Georgia 2015 Freshwater Sport Fishing Regulations, Click on Wild- life Resources Division. Click on Fishing. Choose Fishing Regulations. Or, go to http://www.gofishgeorgia.com For more information on Coastal Fisheries and 2015 Regulations, Click on Coastal Resources Division, or go to http://CoastalGaDNR.org For information on Household Hazardous Waste (HHW) source reduction, reuse options, proper disposal or recycling, go to Georgia Department of Community Affairs at http://www.dca.state.ga.us. Call the DNR Toll Free Tip Line at 1-800-241-4113 to report fish kills, spills, sewer over- flows, dumping or poaching (24 hours a day, seven days a week). Also, report Poaching, via e-mail using [email protected] Check USEPA and USFDA for Federal Guidance on Fish Consumption USEPA: http://www.epa.gov/ost/fishadvice USFDA: http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/seafood.1html Image Credits:Covers: Duane Raver Art Collection, courtesy of the U.S. -

Get to Know Your Neighborhood Turtles! We All Love Turtles

Originally published in the October and November 2017 Woodlake Life on the Lake Newsletter Get to know your neighborhood turtles! We all love turtles. Some of us have pet turtles and some of us are big fans of Ninja turtles. But we can do a little bit more to secure the future of these fascinating creatures. This article introduces the turtles in Woodlake and what can we do to protect them. I was driving on the Woodlake Village Parkway with my daughter, when we spotted a box turtle crossing the road. We changed the lane to avoid hitting the turtle, and turned around hoping to help the turtle cross the road. After 10 seconds, we were so sad to find the crushed turtle on the middle of the road. That was a very upsetting moment for both me and my four year old. May be the driver of the big truck did not see it…or may be the driver was too distracted to avoid it. Vehicle collisions are one of the major causes of turtle mortality. But if we were willing to stop or change the lane, we could have saved many of those turtles! Turtles are fascinating creatures for many reasons! Some ancient civilizations considered turtles as sacred animals and they believed that our world is supported by a giant “cosmic turtle”. Turtles are one of the oldest vertebrate groups on the planet earth, roaming around for about 220 million years, since before the time of dinosaurs. At the same time, turtles have a really long lifespan and scientists believe that many of them can easily surpass 100 years. -

The Spatial Configuration of Greenspace Affects Semi-Aquatic

Landscape and Urban Planning 117 (2013) 46–56 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Landscape and Urban Planning jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landurbplan Research paper The spatial configuration of greenspace affects semi-aquatic turtle occupancy and species richness in a suburban landscape a,∗ b a Jacquelyn C. Guzy , Steven J. Price , Michael E. Dorcas a Department of Biology, Davidson College, Davidson, NC 28035-7118, United States b Department of Forestry, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40546-0073, United States h i g h l i g h t s • We sampled semi-aquatic turtles from 2010 to 2011 at 20 suburban ponds. • We used a hierarchical Bayesian model to estimate species richness and occupancy. • Species richness and occupancy increased with greater connectance of greenspaces. • Richness was greater at golf ponds than rural or urban ponds indicating suitability. • In suburban areas, maintaining connectivity of greenspaces should be a priority. a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Within urbanized areas, the importance of greenspaces for wildlife has been widely investigated for Received 10 April 2012 some animal groups, but reptiles have generally been neglected. To assess the importance of the amount, Received in revised form 17 April 2013 spatial distribution, and configuration of greenspaces (comprised of terrestrial and aquatic areas), we Accepted 24 April 2013 examined semi-aquatic turtle species richness in urbanized areas. In this study, we sampled turtles from 2010 to 2011 at 20 ponds, including farm (rural) ponds, ponds in urbanized environments, and Keywords: golf course ponds. -

The Georgia Coast Saltwater Paddle Trail

2010 The Georgia Coast Saltwater Paddle Trail This project was funded in part by the Coastal Management Program of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, and the U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management (OCRM), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) grant award #NA09NOS4190171, as well as the National Park Service Rivers, Trails & Conservation Assistance Program. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of OCRM or NOAA. September 30, 2010 0 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Coastal Georgia Regional Development Center Project Team .......................................................... 3 Planning and Government Services Staff ................................................................................................... 3 Geographic Information Systems Staff ....................................................................................................... 3 Economic Development Staff .......................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Services Staff .......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Indigenous and Established Herpetofauna of Northwest Louisiana

Indigenous and Established Herpetofauna of Northwest Louisiana Non-venomous Snakes (25 Species) For more info: Buttermilk Racer Coluber constrictor anthicus 318-773-9393 Eastern Coachwhip Coluber flagellum flagellum www.learnaboutcritters.org Prairie Kingsnake Lampropeltis calligaster [email protected] Speckled Kingsnake Lampropeltis holbrooki www.facebook.com/learnaboutcritters Western Milksnake Lampropeltis gentilis Northern Rough Greensnake Opheodrys aestivus aestivus Alligator (1 species) Western Ratsnake Pantherophis obsoletus American Alligator Alligator mississippiensis Slowinski’s Cornsnake † Pantherophis slowinskii Flat-headed Snake † Tantilla gracilis Western Wormsnake † Carphophis vermis Lizards (10 Species) Mississippi Ring-necked Snake Diadophis punctatus stictogenys Western Mudsnake Farancia abacura reinwardtii Northern Green Anole Anolis carolinensis Eastern Hog-nosed Snake Heterodon platirhinos Prairie Lizard Sceloporus consobrinus Mississippi Green Watersnake Nerodia cyclopion Southern Coal Skink † Plestiodon anthracinus pluvialis Plain-bellied Watersnake Nerodia erythrogaster Common Five-lined Skink Plestiodon fasciatus Broad-banded Watersnake Nerodia fasciata confluens Broad-headed Skink Plestiodon laticeps Graham's Crayfish Snake Regina grahamii Southern Prairie Skink † Plestiodon septentrionalis obtusirostris Gulf Swampsnake Liodytes rigida sinicola Little Brown Skink Scincella lateralis Dekay’s Brownsnake Storeria dekayi Eastern Six-lined Racerunner Aspidoscelis sexlineata sexlineata Red-bellied Snake -

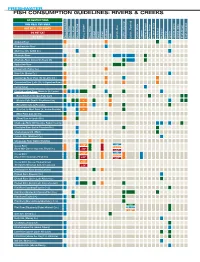

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. -

2014 Coastal Streams

2014 Integrated 305(b)/303(d) List Coastal Streams - Supporting Designated Uses Reach Name/ ID #/ Reach Location/ River Basin/ Criterion Potential Data Source County Use Violated Causes Extent Category Priority Notes Altamaha River Butler River to Altamaha Sound Altamaha 7 miles 1 R030701060509 Glynn/ McIntosh County Fishing 1,5,55 Bungalow Creek Headwaters to Hampton River Altamaha 2 miles 1 R030701060519 Glynn County Fishing 5 Butler River Altamaha River to Altamaha River Altamaha 5 miles 1 (upstream and downstream of I-95) R030701060504 McIntosh County Fishing 5 Darien River Cathead Creek to May Hall Creek Altamaha 5 miles 1 (formerly Cathead Creek to May Creek) R030701060511 McIntosh County Fishing 1,5,55 Hampton River Village Creek to Bungalow Creek Altamaha 1 miles 1 R030701060521 Glynn County Fishing 5 Hampton River Mosquito Creek to Village Creek Altamaha 3 miles 1 R030701060516 Glynn County Fishing 5 Pine Creek Hampton River to the Hampton River Altamaha 2 miles 1 R030701060517 Glynn County Fishing 5 A-326 2014 Integrated 305(b)/303(d) List Coastal Streams - Supporting Designated Uses Reach Name/ ID #/ Reach Location/ River Basin/ Criterion Potential Data Source County Use Violated Causes Extent Category Priority Notes South Altamaha River Altamaha River to Buttermilk Sound Altamaha 15 miles 1 R030701060505 McIntosh/ Glynn County Fishing 5 South Branch (aka Altamaha River to Altamaha River Altamaha 5 miles 1 South Altamaha River) near Cambers Island R030701060510 McIntosh/ Glynn County Fishing 5 Village Creek Bend in Creek at Village Drive to Altamaha 3 miles 1 Hampton River R030701060518 Glynn County Fishing 5 Barbour Island River Wahoo River to Sapelo Sound Ogeechee 8 miles 1 R030602040701 McIntosh County Fishing 5 Bear River Killkenny Creek to St. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

River Highway for Trade, the Savannah : Canoes, Indian Tradeboats

RIVER HIGHWAY FOR TRADE THE SAVANNAH BY RUBY A. RAHN CANOES. INDIAN TRADEBOATS, FLATBOATS, STEAMERS, PACKETS. AND BARGES UG 23 S29 PUBLISHED BY 1968 U. S. ARMY ENGINEER DISTRICT, SAVANNAH CORPS OF ENGINEERS SAVANNAH, GEORGIA JUNE 1968 FOREWORD River Highway for Trade by Ruby A. Rahn is the result of nearly a quarter of a century of research into contemporary newspaper files, old letters, and documents as well as personal memories. Miss Rahn, a long-time school teacher in the school sys tem of Savannah, was born in Effingham County in 1883. She grew up close to the River, during those years when the life and excitement of the River was still a part of local living. Miss Rahn was assisted in the compilation of the monograph by her niece, Naomi Gnann LeBey. The information of the mono graph offers a vivid and valuable record of river activities from the time of Indian habitation through the 19th century. Sometimes supplementary items of the period are included which seem proper in this miscellany of interesting infor mation. M. L. Granger Editor I NTRODUCTI ON I wish to acknowledge with gratitude the help and en couragement received from Mrs. Lilla Hawes, Miss Bessie Lewis, and Mr. Edward Mueller. They were, indeed, friends in my need. The information on the poleboats was all taken from the Marine News reports of the daily newspapers of the time. The totals of cotton bales for these boats can only be ap proximate, as the poleboats were hauling cotton for a few years before the papers started to publish the Marine News.