Community Service and Recidivism: a Study of the Legal And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2017-2018

Annual Report 30 June 2018 Bank of Uganda Annual Report 2017/18 1 Table of Contents Page Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................. 1 List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Abbreviations & Acronyms........................................................................................................................ 4 Registered Addresses.............................................................................................................................. 7 1 Governor’s Foreword ....................................................................................................................... 8 2 Board of Directors and Management Structure ......................................................................................... 9 3 Corporate Governance ................................................................................................................... 11 4 Economic Developments and Prospects ................................................................................................ 22 5 Financial Markets Developments ........................................................................................................ 39 6 Banks Supervision -

Crane Bank to Appeal to Supreme Court

Plot 37/43 Kampala Road, P.O. Box 7120 Kampala Cable Address: UGABANK, Telex: 61069/61244 General Lines: (+256-414) 258441/6, 258061/6, 0312-392000 or 0417-302000. Fax: (+256-414) 233818 Website: www.bou.or.ug E-mail: [email protected] CRANE BANK TO APPEAL TO SUPREME COURT KAMPALA – 30 June 2020 – Bank of Uganda (BoU) wishes to inform the public of its decision to appeal the Court of Appeal’s dismissal of the case filed by Crane Bank Limited (in Receivership) vs. Sudhir Ruparelia and Meera Investments Limited to the Supreme Court. In exercise of its powers under sections 87(3), 88(1)(a)&(b) of the Financial Institutions Act, 2004, BoU placed Crane Bank Ltd (In Receivership) [“Crane Bank”] under Statutory Management on 20th October 2016. This decision was necessary upon discovering that Crane Bank had significant and increasing liquidity problems that could not be resolved without the Central Bank’s intervention given that Crane Bank had failed to obtain credit from anywhere else. An inventory by external auditors found that the assets of Crane Bank were significantly less than its liabilities. In order to protect the financial system and prevent loss to the depositors of Crane Bank, Bank of Uganda had to spend public funds to pay Crane Bank’s depositors. A subsequent forensic investigation as to why Crane Bank became insolvent found a number of wrongful and irregular activities linked to Sudhir Ruparelia and Meera Investments Ltd. These findings form the basis of the claims in the lawsuit by Crane Bank. The suit was necessary for recovery of the taxpayers’ money used to pay depositors’ funds as well as the other liabilities of Crane Bank. -

Umeme Limited FY 2018 Results Presentation Isimba Hydropower

Isimba Hydro Power Dam Isimba Hydropower Station Umeme Limited FY 2018 Results Presentation Contents ❑ Macro Economic Update ❑ Electricity Supply Industry Overview ❑ Umeme Capex Plan ❑ Concession & Regulatory Updates ❑ Operational Review ❑ Financial Highlights ❑ Strategic Priorities 2 Macro Economic Update % GDP Growth Trend 7.0% 6.4% 6.3% 6.4% • Real GDP up 6.1% 6.1% 6.0% 5.6% supported by rise in 5.2% 5.1% 4.8% private sector credit, 5.0% favourable weather 3.8% 3.9% 4.0% 3.6% 3.0% • Gov’t focus on infrastructure supported 2.0% further recovery in 1.0% construction 0.0% 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 • Rebound in services Source: UBOS, Bank of Uganda sector – growth in telecom, financials and ▪ 2018 Headline Inflation average – 2.6% (from 5.6%) insurance ▪ 2018 Currency performance – 2% vs 1% weakening in • Bank of Uganda 2017 Composite Index of Economic Activity points ▪ FY 2018/19 growth projected at 6.3% supported by accommodative monetary policy, infrastructure spending, to improved business stronger credit growth and improved agriculture sentiments performance 3 Installed Generation (MW) Karuma +600 MW 1,800 1,767 Installed Capacity 1,600 Source MW % 1,400 Hydro 927.3 79.5 Isimba +183 Thermal 101.6 8.7 1,167 1,200 (HFO) 984 Solar 40.8 3.5 1,000 905 932 863 872 872 895 Cogeneration 96.2 8.2 800 Diesel 1.0 0.1 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Source: Umeme, UETCL, MEMD Isimba Dam Commissioned on 21st Mar 2019 4 State of Electricity Supply GWh +9.1% MW +5.9% Electricity Sales (GWh) 650 Max System -

Market Update 30 Th October 2017

Market Update th 30 October 2017 USE ALSI Close: 1,685.17 Previous: 1,688.08 (UP:10.27%YTD) - USD/UGX: 3,645.33 Previous: 3,644.92 (Down: 1.15% YTD) USE ALSI* Key Statistics: Market Synopsis: Close 1,685.17 1D* % Change (0.17) Activity on the market at the beginning of the week improved slightly from the previous MTD* % Change (1.85) trading day as Market turnover rose 20.61% to Ugx1.86Mn ($510), Volumes traded also YTD* % Change 10.27 increased to 38,402 from 16,050 shares traded on Friday. Six of the local counters on the bourse were active with DFCU (USE:DFCU) dominating turnover as it posted Ugx910,000 52 Week Range 1,330.82 – 1,837.45 Volume 38,402 with its share price held at Ugx700. Uganda Clays (USE:UCL) and NIC (USE:NIC) made Turnover (ugx) 1.86Mn ($510) upward price movements trading a value of Ugx130,000 and Ugx192,000, both counters PE 9.63 closed at Ugx26 and Ugx12 respectively. Stanbic Bank Uganda (USE:SBU) moved 15,475 EPS 22.73 shares with a value of Ugx421,715, its share price shed 1% while Umeme (USE:UMEM), Dividend Yield 1.8% closed at Ugx430, shedding 1.15%, the counter traded a turnover of Ugx183,610 from 427 Market Cap (ugx) 23,034.41Bn ($6,318.88Mn) shares. Bank of Baroda Uganda (USE:BOBU) traded the least turnover moving only 200 shares with a value of Ugx22,000. The USE All share index (ALSI) lost 0.17% closing at USE ALSI*- USE All Share Index, 1D*- One Day, MTD*- Month to Date, YTD*- Year to Date Source: Uganda Securities Exchange, Bloomberg 1,685.17 from 1,688.08 on Friday, C8, Crested’s local listed companies index declined by 2,000 0.41% to 121.40 while the Local Share Index dropped 0.25% to 386.47. -

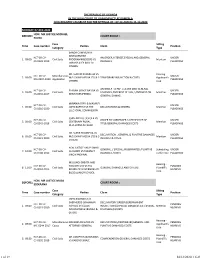

THE REPUBLIC of UGANDA in the HIGH COURT of UGANDA(HCT) at KAMPALA COMMERCIAL REGISTRY CAUSELIST for the SITTINGS of : 08-10-2018 to 12-10-2018

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA(HCT) AT KAMPALA COMMERCIAL REGISTRY CAUSELIST FOR THE SITTINGS OF : 08-10-2018 to 12-10-2018 MONDAY, 08-OCT-2018 BEFORE:: HON MR. JUSTICE DAVID K. WANGUTUSI COURT ROOM :: Time Case number Case Category Pares Claim Sing Type Posion OMEGA CONSTRUCTION LTD VS DECLARATION, SHS 1,344864,116, SHS UNDER 1. 09:00 HCT-00-CC-CS-0247-2017 Civil Suits UGANDA NATUIONAL ROADS Menon 467,327,237, COSTS HEARING AUTHORITY MUGISHA JUSTUS VS DIAMOND DECLARATION, AWARD FOR G/DAMAGES, Hearing - PENDING 2. 09:00 HCT-00-CC-CS-0721-2017 Civil Suits TRUST BANK UGANDA LTD COSTS Plainff's case HEARING BEFORE:: HON. MR. JUSTICE BILLY KAINAMURA COURT ROOM :: Time Case number Case Category Pares Claim Sing Type Posion PEAR ENGINEERING CO, LTD VS Hearing - UNDER 1. 10:00 HCT-00-CC-CS-0728-2013 Civil Suits AFRICAN MEDICAL & RESEARCH SHS. 98,740,410, INTEREST OF 20%, COSTS Plainff's case HEARING FOUNDATION (AMREF) Hearing Miscellaneous ROYAL TRANSIT LTD VS STANDARD UNDER 2. 10:00 HCT-00-CC-MA-1383-2017 INTERIM ORDER, COSTS applicant's Applicaon CHARTERED BANK UGANDA LTD HEARING case STANBIC BANK UGANDA LTD VS Scheduling PENDING 3. 02:00 HCT-00-CC-CS-0672-2013 Civil Suits SHS 438,284,248, INTEREST, & COSTS PAUL GURINDWA & ANOTHER conference HEARING UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS UNDER 4. 02:00 HCT-00-CC-CS-0836-2016 Civil Suits AUTHORITY VS KAAYA USD 25,310.36,INTERST OF 24%, COSTS Menon HEARING ENTERPRISES BEFORE:: HON. LADY JUSTICE ANNA B. MUGENYI COURT ROOM :: Time Case number Case Category Pares Claim Sing Type Posion GODFREY KIRUMIRA KALULE VS UNDER 1. -

Dfcu Group 2017 Annual Report and Financial Statements Who Wewho Are Transformation

2017 Annual Report and Financial Statements Driving Growth through Service & Technology Making More Possible Our mission dfcu seeks to grow shareholder value while playing a key role in transforming the economy and enhancing the well- being of the society. Through our dynamic and responsive teams, we will provide innovative financial solutions and maintain the highest level of customer service and professional integrity. Our vision To be the preferred financial institution, providing a broad range of quality products to our chosen customer segments. Culture competencies 1. Focus on staff and customers 2. Courage 3. Transparency 4. Stewardship 5. Collective effort 6. Decisiveness 7. Pride and Passion dfcu Group 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents and Financial Statements 1 Who we are iv Our purpose v 2 Board of directors vi Women business advisory council viii Senior management team ix 3 List of acronyms and financial definitions x Financial highlights of the year xii 4 Business Updates Rights issue xiii Driving growth through service and technology xiv Driving the economic transformation of women xvi Creating opportunities for business success xvii Partnerships transforming agriculture in Uganda xviii Promoting greater financial inclusion xx Other business highlights xxi Blue Thunder Culture update xxiv Empowering and supporting our communities xxvi 5 Reports Financial overview 2017 xxvii Chairman's report xxxii Business risk report xxxvii Corporate governance xliii Sustainability report l Looking ahead lxiii 6 Financial Statements 1-94 -

East African Prospects

Report East African prospects An update on the political economy of Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda David Booth, Brian Cooksey, Frederick Golooba-Mutebi and Karuti Kanyinga May 2014 May 2014 Report East African prospects An update on the political economy of Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda David Booth, Brian Cooksey, Frederick Golooba-Mutebi and Karuti Kanyinga Prospects in Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda are a matter of small variations and stepwise change within ‘limited access orders’ Pockets of crony capitalist success are set to get larger and more dynamic in Kenya, with some spread effects Political obstacles to coordinated sector reform are going to endure, with especially damaging effects in Tanzania The leadership factors that matter are collective and have to do with political organisation and underlying settlements Reforms could be achieved ‘against the odds’ if practical development organisations were to adopt a different way of working Shaping policy for development odi.org Acknowledgements The authors are grateful to the large number of individuals who shared views and insights on a confidential basis with the research team. The views expressed in the report are, however, those of the authors alone, and we remain responsible for any errors or omissions. No opinions should be attributed to the Overseas Development Institute. East African prospects i Table of contents Acknowledgements i Abbreviations iv Executive summary vii Framing the study vii Kenya viii Tanzania ix Uganda ix Rwanda x Implications and ways -

Court Case Administration System

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA(HCT) AT KAMPALA CIVIL REGISTRY CAUSELIST FOR THE SITTINGS OF : 07-12-2020 to 11-12-2020 MONDAY, 07-DEC-2020 HON. MR JUSTICE MICHAEL BEFORE:: COURT ROOM :: ELUBU Case Sing Time Case number Pares Claim Posion Category Type BANDA COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT HCT-00-CV- AN ORDER,INTEREST,SPECIAL AND GENERAL UNDER 1. 09:00 Civil Suits PROGRAMME(BCDP) VS Menon CS-0349-2019 DAMAGES. PLEADINGS OMONY ALEX AND 10 OTHERS DR. SUDHIR RUPARELIA VS Hearing - HCT-00-CV- Miscellaneous UNDER 2. 09:00 M/S CHIMP MEDIA LTD & 5 TEMPORARY INJUNCTION & COSTS Applicant's MA-0207-2020 Applicaon PLEADINGS OTHERS case AN ORDER TO PAY -150,000 000/ GENERAL HCT-00-CV- ELAISAH GRACE BADDA VS UNDER 3. 09:00 Civil Suits DAMAGES /INTEREST AT 24% / /INTEREST ON Menon CS-0632-2017 DENIS SSEMPEBWA PLEADINGS GENERAL DAMAG MAYANJA FRED & MASAAZI HCT-00-CV- UNDER 4. 09:00 Civil Suits JOHN BAPTIST VS THE DECLARATIONS & ORDERS Menon CS-0216-2020 PLEADINGS ELECTORAL COMMISSION JOAN AKELLO OCHOLA VS HCT-00-CV- ORDER TO SURRENDER A CERTIFICATE OF UNDER 5. 09:00 Civil Suits CENTENARY RURAL Menon CS-0242-2018 TITLE/GENERAL DAMAGES/COSTS PLEADINGS DEVELOPMENT BANK DR. SUHIR RUPARELIA VS HCT-00-CV- DECLARATION , GENERAL & PUNITIVE DAMAGES UNDER 6. 09:00 Civil Suits M/S CHIMP MEDIA LTD & 5 Menon CS-0121-2020 INTEREST & COSTS PLEADINGS OTHERS HON JUSTICE ANUP SINHG HCT-00-CV- GENERAL, / SPECIAL /AGGRAVATED /PUNITIVE Scheduling UNDER 7. 10:00 Civil Suits CHOUDRY VS TARANJIT CS-0748-2016 DAMAGES /COSTS conference PLEADINGS SINGH PADHAAL MULUNGI GREATA AND Hearing - HCT-00-CV- TWO OTHERS VS THE PENDING 8. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements

2012 Annual Report and Financial Statements BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO UGANDA 2012 1 Table of Contents Leaf Operations Sustainable Growth Notice of Annual General Meeting 2 2012 Highlights 4 Uganda has suitable climatic conditions British American Tobacco Uganda is a Board of Directors 6 that support the growth of the highest member of British American Tobacco Group, Directors’ Statement 9 quality leaf. the world’s second largest quoted tobacco group by global market share, with brands Tribute to Dr. James Mulwana 10 sold in more than 180 markets. Managing Director’s Review 12 Working with close to 20,000 farmers, BAT Uganda is the market leader in the tobacco industry in Uganda, with over 80% share of the Statement of Corporate Governance 14 we provide direct agronomy support, cigarette market and sponsoring 70% of national Shareholding Structure 16 covering all aspects of crop production tobacco production. We have sustained a significant presence in Uganda since 1927 when commercial Corporate Information 18 and environmental best practice. tobacco varieties were introduced. Our business has grown to become one of the country’s top Financial Statements 21 tax payers and foreign exchange earners, and we Proxy Form 55 have been listed on the Uganda Securities Exchange Purchasing the crop from farmers since 2000. We are one of the significant sources of through a highly efficient and automated quality tobacco for the BAT Group. buying system at our centres in Hoima, Cigarette Business We market quality cigarette brands that meet the Kihihi, Lira and Arua, ensures prompt preferences of adults who have chosen to consume and secure payments. -

Oxfam in Uganda Inequality Report Compressed

WHO IS GROWING? ENDING INEQUALITY IN UGANDA SECTION 1 2 3 4 5 ENDORSEMENTS HONOURABLE REBECCA A. KADAGA barriers to progress and emancipation, Speaker of Parliament of Uganda especially in a highly patriarchal society like Uganda. I was distressed when one May 2016 morning I received a call from a mother living in one of Through technology, some agencies have done the city slums. She was distraught because a good job fighting inequality and exposing the adjustment government had made to high level corruption. Parliament has done its excise duty on piped water made her unable part to make recommendations for action and to purchase the five twenty-liter jerricans of sanctions. Still, we are yet to see real political water per day for her family’s needs. She could will in stopping corruption. Corruption has been now only afford two jerricans, not enough for institutionalized and no one seems to have the her house chores. At the stroke of a pen, her moral authority to clamp it down. Taxpayers’ life had been drastically altered. I told her I money and morale of Ugandans will continue would ensure a review in the following budget to dissipate until we solve the problem of cycle. corruption which, as Oxfam’s report highlights, remains a major driver of inequality. It is not just taxes that affect lives but also other factors such as access to credit. Despite Parliament’s demands (over the last twenty years) that government establish HIS GRACE STANLEY NTAGALI an agricultural bank for farmers, revive Archbishop of the Church of Uganda cooperative banks and, most importantly, create incentives for financial institutions Oxfam’s report is a revelation to all the people to spread beyond Kampala, Wakiso and of Uganda to look critically, even beyond this Mukono districts, there has been lethargy research. -

Uganda Stock Market Nairobi Stock Exchange September 3

36 BUSINESS VISION,Thursday, September 5, 2013 UGANDA STOCK MARKET NAIROBI STOCK EXCHANGE SEPTEMBER 3 UGANDA CLAYS TO BE MORE AGGRESSIVE PRICE PREVIOUS CHANGE SECTOR PRICE (Ksh) (PERCENT) By SAMUEL SANYA Coffee husks, rice husks, and Securities Exchange since the (Ksh) ground nut husks are being sale of dfcu bank shares to AGRICUltURAL Uganda Clays has appointed considered as alternatives,” he dutch investors for sh111.9b Eaagads Ltd Ord 1.25 25.00 26.00 -3.85 Nazarious Rukanyangira added. in May. Kakuzi Ltd Ord 5.00 90.00 90.00 - as the sales and marketing The company injected The price has since declined Kapchorua Tea Co. Ltd Ord 5.00 122.00 122.00 - manager to spearhead an ag- sh1.5b worth of spares in marginally to sh3,975. Some Limuru Tea Co. Ltd Ord 20.00 490.00 490.00 - gressive expansion strategy in their Kajjansi factory. Current 12,750 shares were sold on Rea Vipingo Plantations Ltd Ord 27.75 27.00 +2.78 East Africa. expensive loans are expected Tuesday for a total turnover of Williamson Tea Kenya Ltd Ord 5.00 250.00 250.00 - Martin Aliker, the Uganda to fully be paid off by March sh50.6m. AUTOMOBILE AND ACCESSORIES Clays chairman, noted at the 2014 to free up space for new A Supreme Court case, costs Car & General (K) Ltd Ord 5.00 25.00 24.75 +1.01 company’s Annual General cheaper financing. related to the decommission- CMC Holdings Ltd Ord 0.50 13.50 13.50 - Meeting at the Sheraton Kam- The company was trading ing of the Kampala processing Marshalls (EA) Ltd Ord 2.00 11.50 11.50 - pala Hotel that the Kamonkoli for sh30 per share by close plant, and an increase in illicit Sameer Africa Ltd Ord 5.00 4.90 4.65 +5.38 branch has been perform- of business on Tuesday. -

Chapter One Introduction

University of Stirling Waswa Balunywa Portfolio Entrepreneurs and Economic Growth: The Case of Uganda A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy i Abstract Many developing countries have not benefited from the technological changes that have taken place over the last 30 years. Uganda has been no exception. The country continues to have over 30 percent of its people below the poverty line. This is despite the appropriateness of macro economic policy and government action in many of these countries. Even in the developed countries, slowness in growth has been attributed to lack of enterprise rather than policy and government action. For this reason, governments and multilateral institutions like the World Bank, have attributed the continued poverty or the slow growth to other factors like governance, institutions but more importantly, entrepreneurship. Classical, and indeed neo-classical economists, did not pay much attention to entrepreneurship as a determinant of growth and therefore this relationship has not been explored in most of the research that has attempted to explain determinants of economic growth. It was Schumpeter who suggested that the entrepreneur had a role in economic growth but no empirical studies have been undertaken to verify this. Thus was until recently when the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) studies were initiated in 1999 led by Paul Reynolds who had done some previous research in this area. The current GEM studies have focused on small firms and yet the model has existing large firms. This study identifies this gap and it is that gap that the study attempts to explain. Having no firm theoretical foundation, the study adopted an inductive approach using mainly qualitative techniques but also adopted quantitative techniques given the nature of the relationship among the variables.