Oxfam in Uganda Inequality Report Compressed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ending Violence Against Women: an Oxfam Guide

ENDING VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN An oxfam Guide Ending Violence Against Women | OXFAM i ii OXFAM | Ending Violence Against Women Contents Why do we work on Violence against women? ……………………………………………………………… 3 What is Violence against women? …………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Key Concepts: …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 What Are the Causes of Violence against women? ……………………………………………… 5 What Does oxfam Do to End Violence against women? ………………………………………………… 7 A Priority Theme for Oxfam ……………………………………………………………………………………… 7 A Rights-Based, Transformative Approach …………………………………………………………… 8 What does “rights-based and transformative” mean in practice? ……………………… 9 Transforming Attitudes and Social norms ………………………………………………………………11 tracking Change ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 14 Theories of Change ……………………………………………………………………………………………………14 Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL): ……………………………………………………………18 Examples from Oxfam programs: ………………………………………………………………………………19 What Can I Do to End Violence against women? ………………………………………………………… 20 Oxfam Programs …………………………………………………………………………………………………………20 Inside Oxfam ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………21 Suggestions for Monitoring …………………………………………………………………………………………… 25 Implementation of the Oxfam Guide on Ending Violence against women ……………25 Questions and Indicators …………………………………………………………………………………………25 Processes for Monitoring and Experience-Sharing ………………………………………………26 Annexes …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 27 Resources …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………27 -

Oxfam COUNTRY Strategy Kenya 2015-2020

Oxfam COUNTRY strategy kenya 2015-2020 INFLUENCING societies Peter a fisherman and trader, fishing in Lake Turkana Photo: Brian Inganga/Oxfam Front cover photo: The women of Nawoyatir village sing and dance in celebration of the arrival of clean water. Photo: Kieran Doherty /Oxfam Vision A transformed Kenyan Society that challenges poverty and inequality to claim their rights Oxfam’s vision is a just world without poverty: a world in which people can influence decisions that affect their lives, enjoy their rights and assume their responsibilities as full citizens of a world in which all human beings are valued and treated equally. context Growth and inequality Kenya has emerged third in the top 20 fastest growing economies in the world in 2015, with an expected growth of 6% (Bloomberg Business, 2015). In 2012, Kenya achieved lower middle income status and was ranked the ninth largest African country with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of $55.2 billion (World Bank, 2014). Despite this positive trend on economic growth, Kenya is one the most unequal countries in the world, with a Gini coefficient of 0.445 (SID,2013). The country’s top 10% households control 42% of total income while the bottom 10% controls less than 1% (SID, 2013). 42% of its 44.4 million people live below the poverty line with wide disparities in the dis- tribution of poverty across the 47 Counties. Kajiado, the least poor County, has a poverty rate of 11% and a poverty gap of 2.5%, com- pared to Turkana, with 94.3% poverty rate and a poverty gap of 67.5%, respectively (CRA Ken- ya County Factsheets, 2011 and 2013). -

Annual Report 2017-2018

Annual Report 30 June 2018 Bank of Uganda Annual Report 2017/18 1 Table of Contents Page Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................. 1 List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Abbreviations & Acronyms........................................................................................................................ 4 Registered Addresses.............................................................................................................................. 7 1 Governor’s Foreword ....................................................................................................................... 8 2 Board of Directors and Management Structure ......................................................................................... 9 3 Corporate Governance ................................................................................................................... 11 4 Economic Developments and Prospects ................................................................................................ 22 5 Financial Markets Developments ........................................................................................................ 39 6 Banks Supervision -

Reconstruction & Poverty Alleviation in Uganda

PRO-POOR GROWTH Tools & Case Studies for Development Specialists RECONSTRUCTION & POVERTY ALLEVIATION IN UGANDA 1987–2001 JANUARY 2005 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by John R. Harris. RECONSTRUCTION & POVERTY ALLEVIATION IN UGANDA 1987–2001 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. i TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................................................... V INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................1 THE SETTING ........................................................................................................................1 Geography and Demographics.................................................................................1 Colonial Period ........................................................................................................2 Post-Independence Regimes ....................................................................................3 Evolution of Uganda’s Economy: 1972–2001.........................................................6 Who Has Benefited from Growth? ........................................................................15 How Did Policy Measures Affect Growth and Poverty Reduction? .....................22 PROSPECTS -

Crane Bank to Appeal to Supreme Court

Plot 37/43 Kampala Road, P.O. Box 7120 Kampala Cable Address: UGABANK, Telex: 61069/61244 General Lines: (+256-414) 258441/6, 258061/6, 0312-392000 or 0417-302000. Fax: (+256-414) 233818 Website: www.bou.or.ug E-mail: [email protected] CRANE BANK TO APPEAL TO SUPREME COURT KAMPALA – 30 June 2020 – Bank of Uganda (BoU) wishes to inform the public of its decision to appeal the Court of Appeal’s dismissal of the case filed by Crane Bank Limited (in Receivership) vs. Sudhir Ruparelia and Meera Investments Limited to the Supreme Court. In exercise of its powers under sections 87(3), 88(1)(a)&(b) of the Financial Institutions Act, 2004, BoU placed Crane Bank Ltd (In Receivership) [“Crane Bank”] under Statutory Management on 20th October 2016. This decision was necessary upon discovering that Crane Bank had significant and increasing liquidity problems that could not be resolved without the Central Bank’s intervention given that Crane Bank had failed to obtain credit from anywhere else. An inventory by external auditors found that the assets of Crane Bank were significantly less than its liabilities. In order to protect the financial system and prevent loss to the depositors of Crane Bank, Bank of Uganda had to spend public funds to pay Crane Bank’s depositors. A subsequent forensic investigation as to why Crane Bank became insolvent found a number of wrongful and irregular activities linked to Sudhir Ruparelia and Meera Investments Ltd. These findings form the basis of the claims in the lawsuit by Crane Bank. The suit was necessary for recovery of the taxpayers’ money used to pay depositors’ funds as well as the other liabilities of Crane Bank. -

Working Together to End Poverty and Injustice

Working together to end poverty and injustice Like slavery and apartheid, poverty is “not natural. It is man-made and it can be overcome. Nelson Mandela at an event organized by Oxfam in London, 2005” Join us. We are Oxfam America. Forty percent of the people on our planet—more than 2.5 billion—live in poverty, struggling to survive on less than $2 a day. Oxfam America is working to change that. In a world rich in resources, we believe poverty can be overcome. Who we are How we work Oxfam America is an international relief and To achieve lasting solutions to poverty, Oxfam development organization that creates lasting relies on the knowledge and insight of those solutions to poverty, hunger, and injustice. affected; we work with local people so they can Founded in 1970, we are part of Oxfam address the causes of poverty themselves. International, a confederation of 13 Oxfams We provide practical assistance to help them working in more than 120 countries, including the become self-sufficient, respond to humanitarian US. Together with individuals and local groups emergencies, and stand up for their rights. in these countries, we save lives, help people We combine this grassroots work with research, overcome poverty, and fight for social justice. education, and global advocacy to change unjust laws and practices that keep people trapped in poverty. Working together to end poverty and injustice oxfam | saving lives Inevitably, disasters strike poor people REBUILDING COMMUNITIES hardest. When a hurricane hits or a violent After the short-term crisis, we tackle the more complex conflict erupts, these are the people least work of helping communities rebuild and come prepared to withstand the trauma, with back stronger. -

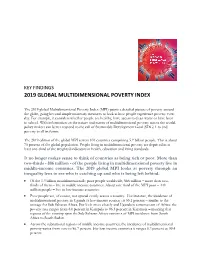

2019 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index

KEY FINDINGS 2019 GLOBAL MULTIDIMENSIONAL POVERTY INDEX The 2019 global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) paints a detailed picture of poverty around the globe, going beyond simple monetary measures to look at how people experience poverty every day. For example, it considers whether people are healthy, have access to clean water or have been to school. With information on the nature and extent of multidimensional poverty across the world, policy makers can better respond to the call of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1 to end poverty in all its forms. The 2019 edition of the global MPI covers 101 countries comprising 5.7 billion people. This is about 76 percent of the global population. People living in multidimensional poverty are deprived in at least one-third of the weighted indicators in health, education and living standards. It no longer makes sense to think of countries as being rich or poor. More than two-thirds - 886 million - of the people living in multidimensional poverty live in middle-income countries. The 2019 global MPI looks at poverty through an inequality lens to see who is catching up and who is being left behind. • Of the 1.3 billion multidimensionally poor people worldwide, 886 million – more than two- thirds of them – live in middle-income countries. About one third of the MPI poor – 440 million people – live in low-income countries. • Poor people are, of course, not spread evenly across a country. For instance, the incidence of multidimensional poverty in Uganda (a low-income country) is 55.1 percent – similar to the average for Sub-Saharan Africa. -

Rule by Law: Discriminatory Legislation and Legitimized Abuses in Uganda

RULE BY LAW DIscRImInAtORy legIslAtIOn AnD legItImIzeD Abuses In ugAnDA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: AFR 59/06/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Ugandan activists demonstrate in Kampala on 26 February 2014 against the Anti-Pornography Act. © Isaac Kasamani amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Introduction -

Umeme Limited FY 2018 Results Presentation Isimba Hydropower

Isimba Hydro Power Dam Isimba Hydropower Station Umeme Limited FY 2018 Results Presentation Contents ❑ Macro Economic Update ❑ Electricity Supply Industry Overview ❑ Umeme Capex Plan ❑ Concession & Regulatory Updates ❑ Operational Review ❑ Financial Highlights ❑ Strategic Priorities 2 Macro Economic Update % GDP Growth Trend 7.0% 6.4% 6.3% 6.4% • Real GDP up 6.1% 6.1% 6.0% 5.6% supported by rise in 5.2% 5.1% 4.8% private sector credit, 5.0% favourable weather 3.8% 3.9% 4.0% 3.6% 3.0% • Gov’t focus on infrastructure supported 2.0% further recovery in 1.0% construction 0.0% 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 • Rebound in services Source: UBOS, Bank of Uganda sector – growth in telecom, financials and ▪ 2018 Headline Inflation average – 2.6% (from 5.6%) insurance ▪ 2018 Currency performance – 2% vs 1% weakening in • Bank of Uganda 2017 Composite Index of Economic Activity points ▪ FY 2018/19 growth projected at 6.3% supported by accommodative monetary policy, infrastructure spending, to improved business stronger credit growth and improved agriculture sentiments performance 3 Installed Generation (MW) Karuma +600 MW 1,800 1,767 Installed Capacity 1,600 Source MW % 1,400 Hydro 927.3 79.5 Isimba +183 Thermal 101.6 8.7 1,167 1,200 (HFO) 984 Solar 40.8 3.5 1,000 905 932 863 872 872 895 Cogeneration 96.2 8.2 800 Diesel 1.0 0.1 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Source: Umeme, UETCL, MEMD Isimba Dam Commissioned on 21st Mar 2019 4 State of Electricity Supply GWh +9.1% MW +5.9% Electricity Sales (GWh) 650 Max System -

Urban Poverty in East Africa: a Comparative Analysis of the Trajectories of Nairobi and Kampala

Urban Poverty in East Africa: a comparative analysis of the trajectories of Nairobi and Kampala Philip Amis University of Birmingham CPRC Working Paper No 39 1 Introduction The aim of this paper is to document and explain the changing nature of urban poverty in East Africa since 1970, in particular in the two cities of Kampala and Nairobi. It will argue that the concept of proleterianization is helpful in understanding the changes in urban poverty and politics. Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania make up the three countries referred to as East Africa. They are contiguous countries; are broadly culturally similar; have a common lingua franca in Kiswahali; share a common history as former British colonies –although Kenya’s history of white European settlement is a crucial difference- and all achieved Independence in the early 1960s and formed the East African community until 1977. Given this background it has been a commonplace in development studies to compare and contrast their experience –this was most clear in the early 1980s- when Tanzania and Kenya were respectively icons of a Socialist and Capitalist models of development. It as hoped that this chapter will provide some background to the subsequent chapters on Kenya and Uganda. History of Proleterinization’s significance to urban Poverty and politics This section is concerned with showing how the process of proleterinization has influenced the nature of urban poverty and politics in a historical context1. In broad terms it is possible to assert that urban wages in Africa have tended to increase in real terms up until the mid 1970s and since then there have been a fairly steady decline (Amis,1989). -

National Housing Policy – May 2016

i FOREWORD Housing is a basic human right, essential for the well-being of all mankind. The 1995 Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, under the General Social and Economic Objectives guarantees to fulfill the fundamental rights of all Ugandans to social justice, economic development, enjoying rights and opportunities and access to clean and safe water, health and decent shelter amongst others. This Housing policy seeks to promote progressive realization of adequate housing for all and is premised on the principle of partnership, involving the Ministry on behalf of Government, the Private sector, Land owner’s, financial institutions, cooperatives and individuals. The role of Government is to provide a conducive policy, legislative and regulatory framework for policy implementation, monitoring and evaluation and its periodical review for effective and efficient policy implementation. Under the partnership framework on policy implementation, Government will provide key inputs such as serviced land with access roads, electricity, water and sewerage, as well as leverage access to affordable financing for housing development. The overall housing situation in the country is characterized by inadequate housing in terms of quality and quantity both in rural and urban areas with a housing deficit of about 1.6 million housing units, out of which 210,000 units are needed in the urban areas. An estimated 900,000 housing units are sub-standard and need replacement or upgrading. The new Housing Policy lays emphasis on regular repair and maintenance of properties. The policy advocates for regular property inspections by competent authorities from the Urban and Local Governments for compliance with building standards. -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE.