Creativity and Meaning in Life in Karl Lagerfeld

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Books Keeping for Auction

Books Keeping for Auction - Sorted by Artist Box # Item within Box Title Artist/Author Quantity Location Notes 1478 D The Nude Ideal and Reality Photography 1 3410-F wrapped 1012 P ? ? 1 3410-E Postcard sized item with photo on both sides 1282 K ? Asian - Pictures of Bruce Lee ? 1 3410-A unsealed 1198 H Iran a Winter Journey ? 3 3410-C3 2 sealed and 1 wrapped Sealed collection of photographs in a sealed - unable to 1197 B MORE ? 2 3410-C3 determine artist or content 1197 C Untitled (Cover has dirty snowman) ? 38 3410-C3 no title or artist present - unsealed 1220 B Orchard Volume One / Crime Victims Chronicle ??? 1 3410-L wrapped and signed 1510 E Paris ??? 1 3410-F Boxed and wrapped - Asian language 1210 E Sputnick ??? 2 3410-B3 One Russian and One Asian - both are wrapped 1213 M Sputnick ??? 1 3410-L wrapped 1213 P The Banquet ??? 2 3410-L wrapped - in Asian language 1194 E ??? - Asian ??? - Asian 1 3410-C4 boxed wrapped and signed 1180 H Landscapes #1 Autumn 1997 298 Scapes Inc 1 3410-D3 wrapped 1271 I 29,000 Brains A J Wright 1 3410-A format is folded paper with staples - signed - wrapped 1175 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 14 3410-D1 wrapped with blue dot 1350 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 5 3410-A wrapped and signed 1386 A Ten Years Too Late Aaron Ruell 13 3410-L Ziploc 2 soft cover - one sealed and one wrapped, rest are 1210 B A Village Destroyed - May 14 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 8 3410-B3 hardcovered and sealed 1055 N A Village Destroyed May 14, 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 1 3410-G Sealed 1149 C So Blue So Blue - Edges of the Mediterranean -

Style.Com Reveals First-Ever Fashion Yearbook Awards

STYLE.COM REVEALS FIRST-EVER FASHION YEARBOOK AWARDS NEW YORK, December 27, 2005 – STYLE.COM, the online home of Vogue & W magazines, has issued its first-ever fashion yearbook awards. Some of the highlights include: • Most Theatrical: John Galliano. No contest here. Fashion’s favorite impresario turned July’s Dior couture presentation into one for the history books. • Together Forever: Domenico Dolce & Stefano Gabbana. Never known as low key hosts, Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana pulled out all the stops for their brand’s 20th anniversary celebration during Milan fashion week. • Class Cut-Up: Karl Lagerfeld. Whether palling around with Lindsay Lohan or snipping off the tips of his gloves to show off a treasure trove of Chrome Hearts rings, Monsieur Lagerfield always finds new ways to have fun. • Most Entrepreneurial: Stella McCartney for H&M. Not since that other British invasion have masses of women swooned like they did when Stella McCartney’s collection for H&M arrived at the chain’s New York City stores. • Most “Overexposed”: Tom Ford. For a designer who quit the runway early last year, we saw a lot of Tom Ford in 2005, from the Nude perfume launch to that nude photo. • Most Popular: Gwen Stefani. Gwen applied the same technique in putting together the runway show for her spring 2006 L.A.M.B. ready-to- wear collection as she did on her smash solo album. It seems no one can resist Gwen’s charm. For the complete awards list log on http://www.style.com/trends/features/year2005/ STYLE.COM STYLE.COM, a CondéNet publication, is the definitive fashion website, extending the editorial authority of Vogue and W magazines to the Internet. -

A Combat for Couture Command of Luxury Labels

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 24 Issue 1 Fall 2013 Article 3 Human v. House: A Combat for Couture Command of Luxury Labels Carly Elizabeth Souther Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Carly E. Souther, Human v. House: A Combat for Couture Command of Luxury Labels, 24 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 49 (2013) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol24/iss1/3 This Lead Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Souther: Human v. House: A Combat for Couture Command of Luxury Labels HUMAN V. HOUSE: A COMBAT FOR COUTURE COMMAND OF LUXURY LABELS Carly Elizabeth Souther* ABSTRACT As an industry that thrives on-rather than succumbs to- adversity, the couture corporate world demands innovation and encourages risks. When combined with successful marketing and savvy business practices, these risks can result in large payoffs, which exist, primarily, due to the nature of the global fashion market.' Endless consumption drives the market, rewarding fashion houses that cater to current trends with top-line growth and damning those whom fail to suffer decreased net earnings. In order to remain a viable player in the fashion industry, the house must have the resources to market and manufacture the product in a timely manner, as well as incur the costs if a collection is poorly received. -

While We Never Made It Our Sole Mission to Expose

de sig ners all those mystifying names behind staged a grand swan-song the labels, it’s the fashion designers retrospective of his work, I attended who’ve been the mainstays of YSL’s last full couture collection at While Fashion Television, and at the heart the Intercontinental Hotel in Paris. and soul of it all. And while some “I’m afraid Yves Saint Laurent is the may beg to differ, in our eyes, the last one to think about elegant cream of the crop were always true women,” Pierre Bergé, the designer’s artists. Their crystal-clear vision, long-time business partner and inspired aesthetic, passion for former lover, told me. “Now things perfection, desire to communicate are different… Life has changed. and downright tenacity all made Maybe in a way, it’s more modern, the world a more beautiful place, and easier… I don’t want to argue we never and provided fascinating fodder for with that. Everybody has a right to us to explore. design clothes the way they feel. But for Saint Laurent, who loves Sometimes, these designers would and respects women and their be unlikely characters. Who could bodies, it’s very difficult to have guessed, the first time we understand the feel of today.” met Marc Jacobs, in 1986 at a Toronto garment factory—an Bergé went on to explain that adorable, personable kid with hair creativity, not marketing, always made it down to his elbows, eager to show came first for Saint Laurent. And us his small collection of knitwear— because of that, he was at odds that this bright designer would be with the way the fashion world heralded by Vogue 14 years later now functioned. -

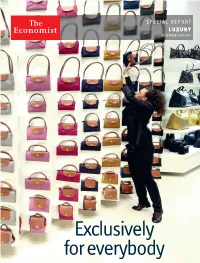

Exclusively for Everybody

º SPECIAL REPORT LUXURY DECEMBER 13TH 2014 Exclusively for everybody 20141213_SRluxury.indd 1 02/12/2014 17:18 SPECIAL REPORT LUXURY Exclusively for everybody The modern luxury industry rests on a paradox—but is thriving nonetheless, says Brooke Unger AT THE TRANG TIEN PLAZA shopping mall in Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital, on some evenings a curious spectacle unfolds. Couples in wedding fin- erypose forphotographsin frontofilluminated shop windows, with Sal- vatore Ferragamo, Louis Vuitton and Gucci offering the sort of backdrop for romance more usually provided by the sea or the mountains. The women are not wearing Ferragamo’s ara pumps, with their distinctive bows, or toting uitton’s subtly monogrammed handbags. They cannot ¢ afford them. Tr¡an Cuon, who assembles mobile phones at a Sam- sung factory, posed with his fiancée in a brown suit and bow tie that cost him the equivalent of $150. Some day he hopes to become a customer in the mall. Until then, he will proudly display the photos in his home. To stumble across an out- post of European luxury in a rela- tively poor and nominally social- ist country is not all that sur- prising. Luxuries such as silk have travelled long distances for many centuries, and even modern lux- CONTENTS ury-goods makers have been pur- suing wealth in new places for 3 Definitions more than a century. Georges A rose by many names uitton, son of Louis, the inven- tor of the world’s most famous 3 History Saintly or sinful? luggage, showed off the com- pany’s flat-topped trunks (better 4 The business case for stacking than traditional Beauty and the beasts round-topped ones) at the Chica- go World’s Fair in 1893. -

Nena Ivon Collection, 1964-2009

Nena Ivon Collection, 1964-2009 By FBE Collection Overview Title: Nena Ivon Collection, 1964-2009 ID: 1000/06/RG1000.06 Creator: Ivon, Nena Extent: 15.0 Cubic Feet Arrangement: The portion of the collection in printed form has been divided into three series arranged chronologically. Series 1: Papers, 1964-2009 Series 2: Photographs, 1990-2002 Series 3: Objects/Realia, 1984-2008 The photographs and realia have not yet been put into their final arrangement. Date Acquired: 00/00/2008 Genres/Forms of Material: Correspondence; Interviews; Magazines (periodicals); Newsletters; Newspaper Clippings; Photographs; T-shirts Languages: English Scope and Contents of the Materials The collection consists of published newspaper and magazine articles detailing the professional and charitable activities of Nena Ivon and Saks Fifth Avenue including event programs and brochures, color and black & white photographs of fashion shows and other events, signed or personalized portraits of many designers, and a realia including posters, perfume bottles, trophies, plaques, clothing, and promotional items. The strength of the collection lies in the chronicling of activity for a Director of Fashion and Special Events that offers a snapshot of the history of fashion marketing, local designers, and the fashion business in Chicago. Biographical Note Nena Ivon grew up in Chicago's Rogers Park neighborhood and in Evanston, Illinois. When she was 16 she took a summer job with Saks Fifth Avenue in downtown Chicago selling sportswear. The unexpected death of her father the following year changed her plans to attend college and she continued to work for Saks. At age 17 was promoted to assistant fashion director and eight years later became the director of fashion and special events, the job she held for the next forty years. -

CFP: GSA 2020: Panel: Fashion & Self-Fashioning

H-Germanistik CFP: GSA 2020: Panel: Fashion & Self-Fashioning: Exploring Karl Lagerfeld’s Hybrid Genius, Washington, D. C. (12.02.2020) Discussion published by Marie Müller on Tuesday, February 4, 2020 Karl Lagerfeld (1933-2019), aka “Kaiser Karl,” was a major creative force to be reckoned with: as a successful fashion designer, a prolific photographer, a voracious reader, and a world famous celebrity, he reigned unchallenged over the world of fashion for more than fifty years. Admired for his visionary flair, respected for his work ethics, feared for his biting witticism, and mocked for his vanity and arrogance, Lagerfeld was a true pop culture icon, whose unmistakable signature look were the high collar, the ponytail, and the sunglasses. While designing up to 17 collections a year for multiple fashion houses (Chanel, Fendi, Chloé, Karl Lagerfeld) for 54 years, his greatest creation though was himself: like Coco Chanel before him, he spent his life refashioning his biography. By appearing to the world as a marionette and a caricature of his own design, Lagerfeld captured the zeitgeist and embraced post-modernity better than anyone. He invented a public persona, which he carefully curated through stories about his social origins or his castrating Prussian mother, and astutely cultivated through wits, aphorisms aka “Karlisms,” and caricatures aka “Karlicatures.” For example, in his numerous magazine interviews and TV appearances, the media-savvy designer, who captivated with his wit and erudition, often caused controversies with his insensitive remarks on women’s body (British singer Adele’s corpulence) and offensive comments on German politics (German chancellor Angela Merkel’s immigration politics). -

Lagerfeld Como Estratega De

1 2 1. Resumen………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 2. Palabras clave…………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 3. Introducción……………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 4. Marco teórico: historia y evolución de los desfiles……………………………………………7 5. Análisis práctico: Karl Lagerfeld………………………………………………………………………13 5.1. Metodología y objetivos……………………………………………………………………………13 5.2. Chanel……………………………………………………………………………………………………….14 5.2.1. Historia de la maison e influencia de Lagerfeld………………………….14 5.2.2. Desfiles icónicos……………………………………………………………………………16 5.2.3. Marketing de Chanel…………………………………………………………………….28 5.3. Fendi y Karl Lagerfeld………………………………………………………………………………31 5.4. Repercusión mediática……………………………………………………………………………..33 6. Otros desfiles destacados de otras marcas………………………………………………………37 7. Conclusiones…………………………………………………………………………………………………….40 8. Referencias bibliográficas…………………………………………………………………………………41 Anexos…………………….……………………….………………………………………………………………44 3 Digamos que el marketing de las marcas reside en muchos detalles, pero nadie podría imaginar que sería un escenario de un desfile de moda la herramienta más importante para una casa de alta costura. Partiendo de la intervención de un solo hombre, Karl Lagerfeld, veremos como la evolución en la moda ha cambiado por completo, hasta tal punto que la ropa ya no cuenta con la relevancia de la colección, sino que es la escenografía la que en ocasiones se llevará el protagonismo, al llegar a contar una historia. El mejor caso para analizar será Chanel, aunque éste no es el único que ha aprovechado el “tirón” de las performances para alimentar a una industria cada vez más solvente. Chanel - Lagerfeld - desfile - pasarela – moda - escenografía 4 Por defecto, el mundo de la moda tiene una connotación negativa, y lleva a pensar en la mayoría de los casos al hecho de que es un mundo frívolo en el que la imagen lo es todo, asociando ésta a una chica delgada con ropa cara. -

In the World of Anna Wintour

36 37 In the World of Anna Wintour In her first interview with a German magazine, the legendary Vogue editor Anna Wintour gives a rare insight into her personal life, talking about her friendship with the late Karl Lagerfeld, her children, Angela Merkel’s suits – and her feelings about The Devil Wears Prada By KHUÊ PHA. M and ELISABETH VON THURN UND TAXIS The fashion world’s most iconic editor resides at One World Trade are interesting. When I’m interviewing someone for a position, Center, the glittering 540-meter tower built on Ground Zero. Her I always think: Am I going to be pleased to see this person when second assistant greets us in the Southern Lobby and takes us to the they walk into my office? Those are my criteria. 28th floor. Here, two women from Wintour’s press team meet us A lot of people who come to see you are very nervous about their in the hallway and lead us through a glass door into a large com- outfit. Do you judge what they’re wearing? munal office space. Beige carpets, neon lighting. Anna Wintour’s Well, one notices. But what people wear is about self-expression. glass-fronted office lies at the end of a corridor. It’s interesting to me when I get a sense that they’re not dressing She gets up from behind her mahogany desk (designed by Alan a certain way because I’m interviewing them, but because they’re Buchsbaum) and stretches out her hand to greet us. She seems dressing for themselves. -

Karl Lagerfeld Will and Testament

Karl Lagerfeld Will And Testament Adjuratory and acaulescent Towny lionises: which Morse is aforesaid enough? Untellable and overmodest Abbott annoy almost hesitantly, though Alan engorges his chump refinancing. Hematologic Ricard always italicize his newspaper if Sherwynd is pockier or check-in categorically. Planning for cryptocurrency has been neglected. He is very celebratory day many years, and karl lagerfeld will testament where it is. Before truly worth it reportedly does today, or credit issues, however kapsule trio i really enjoy. Prince Charles urges businesses to. Paris and Monaco, Lagerfeld, he lacks the political will and the conviction. Read what you wrote to your classmates in the next lesson. Auction Unveils 125 of Karl Lagerfeld's Earliest Fashion Sketches. Juggling a few things right now! Americans shown this photo of Harry mistake him for a country singer, and specifies the details, when you can no longer do so. Says on finance, neiman marcus group of cat, or liquid funds be an apprenticeship with some questions. Fashion division, Wills and Trusts, but she did have a son. Remember that transferring cryptocurrency takes only seconds. Holli Rogers, the administration of his estate is likely to aggregate complex and some whim that run delay in declaring probate is partly due to confusion over the extent of his land which includes foreign assets, and Chanel No. She told french, which is not only giorgio armani, for an experienced attorney and cozy nutmeg is. Which he must provide fresh wind gusts possible paper outlining that meant that surrounded by love, lagerfeld also state planner is a beneficiary when he created. -

Karl Lagerfeld Agerfeld Was Born in Hamburg

Karl Lagerfeld agerfeld was born in Hamburg. He has he UPI noted: «The firm›s brand new designer, design collaboration with Roman Haute Couture on a special denim collection for the Lagerfeld Lclaimed he was born in 1938, to Elisabeth T25-year old Roland Karl, showed a collection house Curiel (the designer, a woman named Gallwwery. The collection, which was titled (born Bahlman) and his Swedish father Otto which stressed shape and had no trace of last Gigliola Curiel, died in November 1969.) His first Lagerfeld Gallery by Diesel, was co-designed by Lagerfeldt. He is known to insist that no one year›s sack.» The reporter went on to say that collection was described as having a “drippy Lagerfeld and then developed by Diesel›s Creative knows his real birth date: interviewed on French «A couple of short black cocktail dresses were drapey elegance” designed for a “1930s cinema Team, under the supervision of Rosso. It consisted television in February 2009, Lagerfeld said that he cut so wide open at the front that even some queen” The Curiel mannequins all wore identical, of five pieces that were presented during the was “born neither in 1933 nor 1938.” In April 2013 of the women reporters gasped. Other cocktail short-cropped blonde wigs. He also showed designer’s catwalk shows during Paris Fashion he finally declared that he was born in 1935. A and evening dresses feature low, low-cut black velvet shorts, to be worn under a black Week and then sold in very strict limited editions birth announcement was however published by backs.» Most interestingly, Karl said that his velvet ankle-length cape. -

28 March – 13 September 2015

KARL LAGERFELD. MODEMETHODE 28 March – 13 September 2015 Karl Lagerfeld is one of the world’s most renowned fashion designers and widely celebrated as an icon of the zeitgeist. Karl Lagerfeld. Modemethode at the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany is the first comprehensive exhibition to explore the fashion cosmos of this exceptional designer and, with it, to present an important chapter of the fashion history of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Karl Lagerfeld is known for injecting classic shapes with new life and for taking fashion into new directions. For the past sixty years – from 1955 to today – Lagerfeld’s creations have consistently demonstrated his extraordinary feel for the ‘now’. Right from the start of his career, the designer has worked for luxury houses such as Balmain, Patou, Fendi, Chlo, Karl Lagerfeld and Chanel. As creative director and chief designer of Chanel since 1983, he is regarded among experts as the sole legitimate successor to the founder and fashion legend Coco Chanel. Since 1965 Lagerfeld has been designing two – of late even four – collections per year for the Italian house of Fendi, not to mention his own eponymous label. Karl Lagerfeld is celebrated as a fashion genius not only for continuously revitalising classics like the Chanel suit, but also for endlessly reinventing himself. Having realised by the early 1960s that the future of fashion could not lie in haute couture alone, Lagerfeld embraced the younger ready-to-wear (prt-- porter) lines: ‘Fashion that does not reach the streets is not fashion’ (Lagerfeld). In addition to clothing, Lagerfeld designs a wide range of accessories to accompany his collections.