Channel Islands Great War Study Group Journal 2 June 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Be a Time Traveller This Summer

BE A TIME TRAVELLER THIS SUMMER 50 THINGS YOU COULD DO THIS SUMMER: Spy for Wall Lizards at ✓ Take an Ice ✓ 1 Mont Orgueil Castle 14 Age Trail* 2 Eat a Jersey Wonder ✓ Find ten French ✓ 15 road names Crawl into the Neolithic Visit a Société Jersiaise ✓ 3 Passage Grave at ✓ 16 Dolmen* La Hougue Bie Listen to the Goodwyf ✓ Discover the 17 at Hamptonne 4 Celtic Coin Hoard ✓ at Jersey Museum Meet George, the 100 year ✓ 18 old tortoise at Durrell Visit the Ice Age 5 ✓ Dig at Les Varines (July)* Download the Jersey Heritage ✓ 19 Digital Pocket Museum 6 Visit 16 New Street ✓ 20 See the Devil at Devil’s Hole ✓ Sing Jèrriais with the Make a Papier-mâché 7 Badlabecques* ✓ 21 ✓ www.jerseyheritage.org/kids dinosaur at home Count the rings on a tree Draw your favourite ✓ 22 ✓ 8 place in Jersey stump to see how old it is Search for gun-shot marks Climb to the top ✓ 23 ✓ 9 of a castle in the Royal Square Discover Starry Starry Nights Look out for 24 ✓ the Perseid at La Hougue Bie 3 August 10 ✓ Meteor Shower Explore the Globe Room at ✓ August 11-13 25 the Maritime Museum 11 Picnic at Grosnez Castle ✓ Look for the Black Dog 12 of Bouley Bay at the ✓ Maritime Museum See the Noon Day Gun at 13 ✓ Elizabeth Castle For more details about these fun activities, visit www.jerseyheritage.org/kids *Free Guide & videos on the Jersey Heritage website Try abseiling with Castle ✓ Catch Lillie, Major Peirson & ✓ 26 Adventures 41 Terence - Le Petit Trains Dress up as a princess or Look for the rare Bosdet 27 ✓ soldier at Mont Orgueil Castle 42 painting at St -

The Jersey Heritage Answersheet

THE JERSEY HERITAGE Monuments Quiz ANSWERSHEET 1 Seymour Tower, Grouville Seymour Tower was built in 1782, 1¼ miles offshore in the south-east corner of the Island. Jersey’s huge tidal range means that the tower occupies the far point which dries out at low tide and was therefore a possible landing place for invading troops. The tower is defended by musket loopholes in the walls and a gun battery at its base. It could also provide early warning of any impending attack to sentries posted along the shore. 2 Faldouet Dolmen, St Martin This megalithic monument is also known as La Pouquelaye de Faldouët - pouquelaye meaning ‘fairy stones’ in Jersey. It is a passage grave built in the middle Neolithic period, around 4000 BC, the main stones transported here from a variety of places up to three miles away. Human remains were found here along with finds such as pottery vessels and polished stone axes. 3 Cold War Bunker, St Helier A German World War II bunker adapted for use during the Cold War as Jersey’s Civil Emergency Centre and Nuclear Monitoring Station. The building includes a large operations room and BBC studio. 4 Statue of King George V in Howard Davis Park Bronze statue of King George V wearing the robes of the Sovereign of the Garter. Watchtower, La Coupe Point, St Martin 5 On the highest point of the headland is a small watchtower built in the early 19th century and used by the Royal Navy as a lookout post during the Napoleonic wars. It is sturdily constructed of mixed stone rubble with a circular plan and domed top in brick. -

Heritage and Culture

Jersey’s Coastal Zone Management Strategy Heritage and Culture Jersey’s Coastal Zone Management Strategy aims to achieve integrated management of the whole of the Island’s inshore waters out to the Jersey maritime boundary for the first time. Seymour Tower © Jersey Tourism 1 Contents 1. HERITAGE & CULTURE IN JERSEY.............................................................................. 4 2. THE POLICY FRAMEWORK FOR HERITAGE AND CULTURE IN THE COASTAL ZONE......................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1. COUNCIL OF EUROPE CULTURAL CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE OF EUROPE GRANADA 1985, REVISED VALETTA, 1992 .................... 4 2.2. THE CROWN ESTATE .................................................................................................. 5 2.3. ISLAND PLANNING (JERSEY) LAW 1964, AS AMENDED................................................... 5 2.4. ISLAND PLAN 2002 ..................................................................................................... 5 2.5. SHIPPING (JERSEY) LAW 2002.................................................................................... 6 3. HISTORIC PORTS & COASTAL DEFENCE................................................................... 6 3.1. MILITARY DEFENCE FORTIFICATIONS ........................................................................... 6 3.2. HISTORIC PORTS ....................................................................................................... -

Valuing the Heritage of the Channel Islands

Valuing the Heritage of the Channel Islands Kate Clark Kate Clark Associates Heritage policy, practice & planning Elizabeth Castle, Jersey Valuing the Heritage of the Channel Islands An initial assessment against World Heritage Site criteria and Public Value criteria Kate Clark Kate Clark Associates For Jersey Heritage August 2008. List of Contents Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 Summary Recommendations 8 Recommendation One: Do more to capture the value of Jersey’s Heritage Recommendation Two: Explore a World Heritage bid for the Channel Islands Chapter One - Valuing heritage 11 1.1 Gathering data about heritage 1.2 Research into the value of heritage 1.3 Public value Chapter Two – Initial assessment of the heritage of the Channel Islands 19 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Geography and politics 2.3 Brief history 2.4 Historic environment 2.5 Intangible heritage 2.6 Heritage management in the Channel Islands 2.7 Issues Chapter Three – capturing the value of heritage in the Channel Islands 33 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Intrinsic value 3.3 Instrumental benefits 3.4 Institutional values 3.5 Recommendations 4 Chapter Four – A world heritage site bid for the Channel Islands 37 4.0 Introduction 4.1 World heritage designation 4.2 The UK tentative list 4.3 The UK policy review 4.4 A CI nomination? 4.5 Assessment against World Heritage Criteria 4.6 Management criteria 4.7 Recommendations Conclusions 51 Appendix One – Jersey’s fortifications 53 A 1.1 Historic fortifications A 1.2 A brief history of fortification in Jersey A 1.3 Fortification sites A 1.4 Brief for further work Appendix Two – the UK Tentative List 67 Appendix Three – World Heritage Sites that are fortifications 71 Appendix Four – assessment of La Cotte de St Brelade 73 Appendix Five – brief for this project 75 Bibliography 77 5 Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the very kind support, enthusiasm, time and hospitality of John Mesch and his colleagues of the Société Jersiase, including Dr John Renouf and John Stratford. -

Heroes, Myths and Legends of the East

EAST - TRAIL Heroes, Myths and Legends of The East The eastern trail takes you from the eastern N suburbs of St. Helier, along the coast towards the small harbour of Gorey and its iconic castle. It then goes to St. Catherine’s and La Hougue Bie. W S This trail can be completed in half a day, but if E you wish to visit La Hougue Bie, Mont Orgueil Castle and Samarès Manor it would probably take a full day. Approximately 12 miles / 19 km GPS 49.1734, -2.0780 GPS 49.1670, -2.0616 1 3 Samarès Manor Le Hocq Sir James Knot General Conway – There are many Jersey Samarès Manor is worth a visit especially if you Round Towers built in the late 1700s to protect are interested in gardens. It is one of the ancient the island against invasion from the French. manors of the island and has been changed and General Conway was the man who ordered these renovated over the years. Sir James Knot and his defences to be built. They are about 500 metres descendants are the most recent inhabitants. apart and there are still 17 left. He was a shipping magnate who bought the manor in 1924. There is a trust fund in his name which supports projects in the North East of GPS 49.1639, -2.0335 England, where he was from, and Jersey. 4 La Rocque Harbour Baron de Rullecourt and the Battle of Jersey 5/6th January 1781 - it was at this point that Baron GPS 49.1634, -2.0738 De Rullecourt landed with around 600 infantrymen 2 Green Island of the original 1500 he set out with. -

Jersey Heritage Trust High Level Review of Operational Performance

Jersey Heritage Trust High level review of operational performance Economic Development Department February 2010 Locum Consulting 9 Marylebone Lane London W1U 1HL United Kingdom T: +44 (0) 20 7487 1799 F: +44 (0) 20 7344 6558 [email protected] www.locumconsulting.com Date: 08 March 2010 Job: J0968 File: j0968 jht review report final 100215 All information, analysis and recommendations made for clients by Locum Consulting are made in good faith and represent Locum’s professional judgement on the basis of information obtai ned from the client and elsewhere during the course of the assignment. However, since the achievement of recommendations, forecasts and valuations depends on factors outside Locum’s control, no statement made by Locum may be deemed in any circumstances to be a representation, undertaking or warranty, and Locum cannot accept any liability should such statements prove to be inaccurate or based on incorrect premises. In particular, and without limiting the generality of the foregoing, any projections, financia l and otherwise, in this report are intended only to illustrate particular points of argument and do not constitute forecasts of actual performance. Locum Consulting is the trading name of Locum Destination Consulting Ltd. Registered in England No. 3801514 Jersey Heritage Trust Contents 1. Introduction 4 1.1 The Study Brief 4 1.2 Our Approach to the Study 4 1.3 Limitations 5 1.4 Acknowledgements 5 1.5 Structure of this Report 5 2. Summary of Conclusions 7 2.1 Market Performance Findings 7 2.2 Operational Performance Findings 7 2.3 Conclusions and Recommendations 8 3. Background 10 3.1 The JHT 10 3.2 What Has Gone Before 10 3.3 The Current Financial Position and ‘Gap’ 11 3.4 The Market in which JHT Operates 12 4. -

Jersey's Spiritual Landscape

Unlock the Island with Jersey Heritage audio tours La Pouquelaye de Faldouët P 04 Built around 6,000 years ago, the dolmen at La Pouquelaye de Faldouët consists of a 5 metre long passage leading into an unusual double chamber. At the entrance you will notice the remains of two dry stone walls and a ring of upright stones that were constructed around the dolmen. Walk along the entrance passage and enter the spacious circular main Jersey’s maritime Jersey’s military chamber. It is unlikely that this was ever landscape landscape roofed because of its size and it is easy Immerse Download the FREE audio tour Immerse Download the FREE audio tour to imagine prehistoric people gathering yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org the history the history here to worship and perform rituals. and stories and stories of Jersey of Jersey La Hougue Bie N 04 The 6,000-year-old burial site at Supported by Supported by La Hougue Bie is considered one of Tourism Development Fund Tourism Development Fund the largest and best preserved Neolithic passage graves in Europe. It stands under an impressive mound that is 12 metres high and 54 metres in diameter. The chapel of Notre Dame de la Clarté Jersey’s Maritime Landscape on the summit of the mound was Listen to fishy tales and delve into Jersey’s maritime built in the 12th century, possibly Jersey’s spiritual replacing an older wooden structure. past. Audio tour and map In the 1990s, the original entrance Jersey’s Military Landscape to the passage was exposed during landscape new excavations of the mound. -

THE STATES Assembled on Tuesday, 18Th March 2003 at 9.30 A.M. Under the Presidency of Michael Nelson De La Haye Esquire, Greffier of the States

THE STATES assembled on Tuesday, 18th March 2003 at 9.30 a.m. under the Presidency of Michael Nelson de la Haye Esquire, Greffier of the States. His Excellency the Lieutenant Governor, Air Chief Marshal Sir John Cheshire, K.B.E., C.B., was present All members were present with the exception of – Francis Herbert Amy, Connétable of Grouville – ill John Baudains Germain, Connétable of St. Martin – ill John Le Sueur Gallichan, Connétable of Trinity – out of the Island Jeremy Laurence Dorey, Deputy of St. Helier – out of the Island Prayers Subordinate legislation tabled The following enactments were laid before the States, namely – Nursing Homes and Mental Nursing Homes (General Provisions) (Amendment R&O 16/2003. No. 9) (Jersey) Order 2003. Terrorism (Enforcement of British Islands Orders) (Jersey) Rules 2003. R&O 17/2003. Residential Homes (General Provisions) (Amendment No. 9) (Jersey) Order 2003. R&O 18/2003. Committee for Postal Administration – resignation of members THE STATES noted the resignation of Senator Terence Augustine Le Sueur, Deputy Jacqueline Jeannette Huet of St. Helier and Deputy Roy George Le Hérissier of St. Saviour from the Committee for Postal Administration. Committee for Postal Administration – constitution and appointment of members THE STATES, in accordance with Article 28(2)(b) of the States of Jersey Law 1966, as amended, and on a proposition of Deputy Patrick John Dennis Ryan of St. Helier, President of the Committee for Postal Administration, determined that the Committee for Postal Administration should, henceforth, consist of the President and four other elected members of the States. THE STATES appointed the following as members – The Connétable of St. -

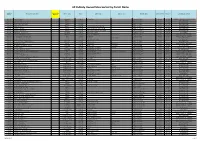

All Publicly Owned Sites Sorted by Parish Name

All Publicly Owned Sites Sorted by Parish Name Sorted by Proposed for Then Sorted by Site Name Site Use Class Tenure Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Vingtaine Name Address Parish Postcode Controlling Department Parish Disposal Grouville 2 La Croix Crescent Residential Freehold La Rue a Don Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DA COMMUNITY & CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS Grouville B22 Gorey Village Highway Freehold Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9EB INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B37 La Hougue Bie - La Rocque Highway Freehold Vingtaine de la Rue Grouville JE3 9UR INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B70 Rue a Don - Mont Gabard Highway Freehold Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 6ET INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B71 Rue des Pres Highway Freehold La Croix - Rue de la Ville es Renauds Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DJ INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville C109 Rue de la Parade Highway Freehold La Croix Catelain - Princes Tower Road Vingtaine de Longueville Grouville JE3 9UP INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville C111 Rue du Puits Mahaut Highway Freehold Grande Route des Sablons - Rue du Pont Vingtaine de la Rocque Grouville JE3 9BU INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville Field G724 Le Pre de la Reine Agricultural Freehold La Route de Longueville Vingtaine de Longueville Grouville JE2 7SA ENVIRONMENT Grouville Fields G34 and G37 Queen`s Valley Agricultural Freehold La Route de la Hougue Bie Queen`s Valley Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9EW HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES Grouville Fort William Beach Kiosk Sites 1 & 2 Land Freehold La Rue a Don Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DY JERSEY PROPERTY HOLDINGS -

Jersey's Military Landscape

Unlock the Island with Jersey Heritage audio tours that if the French fleet was to leave 1765 with a stone vaulted roof, to St Malo, the news could be flashed replace the original structure (which from lookout ships to Mont Orgueil (via was blown up). It is the oldest defensive Grosnez), to Sark and then Guernsey, fortification in St Ouen’s Bay and, as where the British fleet was stationed. with others, is painted white as a Tests showed that the news could navigation marker. arrive in Guernsey within 15 minutes of the French fleet’s departure! La Rocco Tower F 04 Standing half a mile offshore at St Ouen’s Bay F 02, 03, 04 and 05 the southern end of St Ouen’s Bay In 1779, the Prince of Nassau attempted is La Rocco Tower, the largest of to land with his troops in St Ouen’s Conway’s towers and the last to be Jersey’s spiritual Jersey’s maritime bay but found the Lieutenant built. Like the tower at Archirondel landscape Governor and the Militia waiting for it was built on a tidal islet and has a landscape Immerse Download the FREE audio tour Immerse Download the FREE audio tour him and was easily beaten back. surrounding battery, which helps yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org the history the history However, the attack highlighted the give it a distinctive silhouette. and stories and stories need for more fortifications in the area of Jersey of Jersey and a chain of five towers was built in Portelet H 06 the bay in the 1780s as part of General The tower on the rock in the middle Supported by Supported by Henry Seymour Conway’s plan to of the bay is commonly known as Tourism Development Fund Tourism Development Fund fortify the entire coastline of Jersey. -

31 St Saviour Q2 2016.Pdf

StSaviour-SUMMER-2016-31.qxp_Governance style ideas 15/06/2016 16:21 Page 1 SUMMER 2016 Esprit de St Sauveur Edition31 New Parish ambassadors crowned In this issue p 4 Out and about p9 From the Connétable p 9 From the Deputy p11 Parish churches p14 Parish Clubs & Associations p19 Parish sports p35 Parish schools p38 From the Parish Hall ExpExpererienciencee ha haasas its its rreewarardsds QUENNEVVAISAIS TTel:el: 7474747 777 GOREY www.bbest.je StSaviour-SUMMER-2016-31.qxp_Governance style ideas 15/06/2016 16:21 Page 2 A true community atmosphere The Willows inspires a true community atmosphere, with a central village green – home to enchanting old willow trees, which provide a touch of shade and an ideal place to sit and read, or watch the children play. The far southeast corner of Jersey proffers Jersey’s auspicious coastal treasures are as The amply sized 3 one of the island’s most picturesque seings contrasting as they are beautiful and Gorey bedroom houses start – a marina overlooked by a formidable is a wonderful culmination of all the wonder from £675,000 and the medieval castle, tucked across from the that makes the island so unique. Countryside, beautiful 4 bedroom coast road and its belt of golden sand. beaches and breathtaking views of the houses start at £745,000. magnificent Mont Orgueil Castle atop the Situated on the site where poers once spun To arrange a viewing at pier and undeniably prey marina, make for their now collectable ware and visitors would the Willows or our other an ideal backdrop to one of the island’s most marvel at the beautiful gardens, The Willows new build developments charming locations; Gorey Village. -

Guernsey, 1814-1914: Migration in a Modernising Society

GUERNSEY, 1814-1914: MIGRATION IN A MODERNISING SOCIETY Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Rose-Marie Anne Crossan Centre for English Local History University of Leicester March, 2005 UMI Number: U594527 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U594527 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 GUERNSEY, 1814-1914: MIGRATION IN A MODERNISING SOCIETY ROSE-MARIE ANNE CROSSAN Centre for English Local History University of Leicester March 2005 ABSTRACT Guernsey is a densely populated island lying 27 miles off the Normandy coast. In 1814 it remained largely French-speaking, though it had been politically British for 600 years. The island's only town, St Peter Port (which in 1814 accommodated over half the population) had during the previous century developed a thriving commercial sector with strong links to England, whose cultural influence it began to absorb. The rural hinterland was, by contrast, characterised by a traditional autarkic regime more redolent of pre industrial France. By 1914, the population had doubled, but St Peter Port's share had fallen to 43 percent.