The Mediant Relations in Amy Beach's Variations On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Corigliano's Fantasia on an Ostinato, Miguel Del Aguila's Conga for Piano, and William Bolcom's Nine New Bagatelles

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2016 Pedagogical and Performance Aspects of Three American Compositions for Solo Piano: John Corigliano's Fantasia on an Ostinato, Miguel del Aguila's Conga for Piano, and William Bolcom's Nine New Bagatelles Tse Wei Chai Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Chai, Tse Wei, "Pedagogical and Performance Aspects of Three American Compositions for Solo Piano: John Corigliano's Fantasia on an Ostinato, Miguel del Aguila's Conga for Piano, and William Bolcom's Nine New Bagatelles" (2016). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5331. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5331 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pedagogical and Performance Aspects of Three American Compositions for Solo Piano: John Corigliano’s Fantasia on an Ostinato, Miguel del Aguila’s Conga for Piano, and William Bolcom’s Nine New Bagatelles Tse Wei Chai A Doctoral Research Project submitted to The College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance James Miltenberger, D.M.A., Committee Chair & Research Advisor Peter Amstutz, D.M.A. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 88

BOSTON SYMPHONY v^Xvv^JTa Jlj l3 X JlVjl FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON THURSDAY A SERIES EIGHTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1968-1969 Exquisite Sound From the palaces of ancient Egypt to the concert halls of our modern cities, the wondrous music of the harp has compelled attention from all peoples and all countries. Through this passage of time many changes have been made in the original design. The early instruments shown in drawings on the tomb of Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C.) were richly decorated but lacked the fore-pillar. Later the "Kinner" developed by the Hebrews took the form as we know it today. The pedal harp was invented about 1720 by a Bavarian named Hochbrucker and through this ingenious device it be- came possible to play in eight major and five minor scales complete. Today the harp is an important and familiar instrument providing the "Exquisite Sound" and special effects so important to modern orchestration and arrange- ment. The certainty of change makes necessary a continuous review of your insurance protection. We welcome the opportunity of providing this service for your business or personal needs. We respectfully invite your inquiry CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts Telephone 542-1250 PAIGE OBRION RUSSELL Insurance Since 1876 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Music Director CHARLES WILSON Assistant Conductor EIGHTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1968-1969 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President HAROLD D. HODGKINSON PHILIP K. ALLEN Vice-President E. MORTON JENNINGS JR ROBERT H.GARDINER Vice-President EDWARD M. -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

On Modulation —

— On Modulation — Dean W. Billmeyer University of Minnesota American Guild of Organists National Convention June 25, 2008 Some Definitions • “…modulating [is] going smoothly from one key to another….”1 • “Modulation is the process by which a change of tonality is made in a smooth and convincing way.”2 • “In tonal music, a firmly established change of key, as opposed to a passing reference to another key, known as a ‘tonicization’. The scale or pitch collection and characteristic harmonic progressions of the new key must be present, and there will usually be at least one cadence to the new tonic.”3 Some Considerations • “Smoothness” is not necessarily a requirement for a successful modulation, as much tonal literature will illustrate. A “convincing way” is a better criterion to consider. • A clear establishment of the new key is important, and usually a duration to the modulation of some length is required for this. • Understanding a modulation depends on the aural perception of the listener; hence, some ambiguity is inherent in distinguishing among a mere tonicization, a “false” modulation, and a modulation. • A modulation to a “foreign” key may be easier to accomplish than one to a diatonically related key: the ear is forced to interpret a new key quickly when there is a large change in the number of accidentals (i.e., the set of pitch classes) in the keys used. 1 Max Miller, “A First Step in Keyboard Modulation”, The American Organist, October 1982. 2 Charles S. Brown, CAGO Study Guide, 1981. 3 Janna Saslaw: “Modulation”, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 5 May 2008), http://www.grovemusic.com. -

December 3, 2006 2595Th Concert

For the convenience of concertgoers the Garden Cafe remains open until 6:00 pm. The use of cameras or recording equipment during the performance is not allowed. Please be sure that cell phones, pagers, and other electronic devices are turned off. Please note that late entry or reentry of The Sixty-fifth Season of the West Building after 6:30 pm is not permitted. The William Nelson Cromwell and F. Lammot Belin Concerts “Sixty-five, but not retiring” National Gallery of Art Music Department 2,595th Concert National Gallery of Art Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue nw Washington, DC Shaun Tirrell, pianist Mailing address 2000B South Club Drive Landover, md 20785 www.nga.gov December 3, 2006 Sunday Evening, 6:30 pm West Building, West Garden Court Admission free Program Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757) Sonata in F Minor, K. 466 (1738) Frederic Chopin (1810-1849) Ballade in F Major, op. 38 (1840) Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Funerailles (1849) Vallot d’Obtrmann (1855) INTERMISSION Sergey Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) Sonata no. 2 in B-flat Minor, op. 36 (1913) The Mason and Hamlin concert grand piano used in this performance Allegro agitato was provided by Piano Craft of Gaithersburg, Maryland. Lento Allegro molto The Musician Program Notes Shaun Tirrell is an internationally acclaimed pianist who has made his In this program, Shaun Tirrell shares with the National Gallery audience his home in the Washington, dc, area since 1995. A graduate of the Peabody skill in interpreting both baroque and romantic music. To represent the music Conservatory of Music in Baltimore, where he studied under Julian Martin of the early eighteenth-century masters of the harpsichord (the keyboard and earned a master of music degree and an artist diploma, he received a instrument of choice in that era), he has chosen a sonata by Domenico rave review in the Washington Post for his 1995 debut recital at the Kennedy Scarlatti. -

Eduqas-Bach-Badinerie-Musical-Analysis.Pdf

Musical Analysis Bach: Badinerie J.S.Bach: BADINERIE from Orchestral Suite No.2 Melodic Analysis The entire movement is based on two musical motifs: X and Y. Section A Bars 02 – 161 Sixteen bars Bars 02 – 21 The movement opens with the first statement of motif X, which is played by the flute. The motif is a descending B minor arpeggio/broken chord with a characteristic quaver and semiquaver(s) rhythm. Bars 22 – 41 The melodic material remains with the flute for the first statement of motif Y. This motifis an ascending semiquaver figure consisting of both arpeggios/broken chords sand conjunct movement. Bars 42 – 61 Motif X is then restated by the flute. Music | Bach: Badinerie - Musical Analysis 1 Musical Analysis Bach: Badinerie Bars 62 – 81 Motif X is presented by the cellos in a slightly modified version in which the last crotchet of the motif is replaced with a quaver and two semiquavers. This motif moves the tonality to A major and is also the initial phrase in a musical sequence. Bars 82 – 101 Motif X remains with the cellos with a further modified ending in which the last crotchet is replaced with four semiquavers. It moves the tonality to the dominant minor, F# minor, and is the answering phrase in a musical sequence that began in bar 62. Bars 102 – 121 Motif Y returns in the flute part with a modified ending in which the last two quavers are replaced by four semiquavers. Bars 122 – 161 The flute continues to present the main melodic material. Motif Y is both extended and developed, and Section A is brought to a close in F# minor. -

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors Richard Bass Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 38, No. 2. (Autumn, 1994), pp. 155-186. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-2909%28199423%2938%3A2%3C155%3AMOOAWI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-X Journal of Music Theory is currently published by Yale University Department of Music. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/yudm.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Jul 30 09:19:06 2007 MODELS OF OCTATONIC AND WHOLE-TONE INTERACTION: GEORGE CRUMB AND HIS PREDECESSORS Richard Bass A bifurcated view of pitch structure in early twentieth-century music has become more explicit in recent analytic writings. -

Day 17 AP Music Handout, Scale Degress.Mus

Scale Degrees, Chord Quality, & Roman Numeral Analysis There are a total of seven scale degrees in both major and minor scales. Each of these degrees has a name which you are required to memorize tonight. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 & w w w w w 1. tonicw 2.w supertonic 3.w mediant 4. subdominant 5. dominant 6. submediant 7. leading tone 1. tonic A triad can be built upon each scale degree. w w w w & w w w w w w w w 1. tonicw 2.w supertonic 3.w mediant 4. subdominant 5. dominant 6. submediant 7. leading tone 1. tonic The quality and scale degree of the triads is shown by Roman numerals. Captial numerals are used to indicate major triads with lowercase numerals used to show minor triads. Diminished triads are lowercase with a "degree" ( °) symbol following and augmented triads are capital followed by a "plus" ( +) symbol. Roman numerals written for a major key look as follows: w w w w & w w w w w w w w CM: wI (M) iiw (m) wiii (m) IV (M) V (M) vi (m) vii° (dim) I (M) EVERY MAJOR KEY FOLLOWS THE PATTERN ABOVE FOR ITS ROMAN NUMERALS! Because the seventh scale degree in a natural minor scale is a whole step below tonic instead of a half step, the name is changed to subtonic, rather than leading tone. Leading tone ALWAYS indicates a half step below tonic. Notice the change in the qualities and therefore Roman numerals when in the natural minor scale. -

AP Music Theory Course Description Audio Files ”

MusIc Theory Course Description e ffective Fall 2 0 1 2 AP Course Descriptions are updated regularly. Please visit AP Central® (apcentral.collegeboard.org) to determine whether a more recent Course Description PDF is available. The College Board The College Board is a mission-driven not-for-profit organization that connects students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the College Board was created to expand access to higher education. Today, the membership association is made up of more than 5,900 of the world’s leading educational institutions and is dedicated to promoting excellence and equity in education. Each year, the College Board helps more than seven million students prepare for a successful transition to college through programs and services in college readiness and college success — including the SAT® and the Advanced Placement Program®. The organization also serves the education community through research and advocacy on behalf of students, educators, and schools. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.org. AP Equity and Access Policy The College Board strongly encourages educators to make equitable access a guiding principle for their AP programs by giving all willing and academically prepared students the opportunity to participate in AP. We encourage the elimination of barriers that restrict access to AP for students from ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups that have been traditionally underserved. Schools should make every effort to ensure their AP classes reflect the diversity of their student population. The College Board also believes that all students should have access to academically challenging course work before they enroll in AP classes, which can prepare them for AP success. -

Conducting from the Piano: a Tradition Worth Reviving? a Study in Performance

CONDUCTING FROM THE PIANO: A TRADITION WORTH REVIVING? A STUDY IN PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: MOZART’S PIANO CONCERTO IN C MINOR, K. 491 Eldred Colonel Marshall IV, B.A., M.M., M.M, M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2018 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor David Itkin, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Marshall IV, Eldred Colonel. Conducting from the Piano: A Tradition Worth Reviving? A Study in Performance Practice: Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C minor, K. 491. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2018, 74 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. Is conducting from the piano "real conducting?" Does one need formal orchestral conducting training in order to conduct classical-era piano concertos from the piano? Do Mozart piano concertos need a conductor? These are all questions this paper attempts to answer. Copyright 2018 by Eldred Colonel Marshall IV ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: A BRIEF HISTORY OF CONDUCTING FROM THE KEYBOARD ............ 1 CHAPTER 2. WHAT IS “REAL CONDUCTING?” ................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER 3. ARE CONDUCTORS NECESSARY IN MOZART PIANO CONCERTOS? ........................... 13 Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-flat major, K. 271 “Jeunehomme” (1777) ............................... 13 Piano Concerto No. 13 in C major, K. 415 (1782) ............................................................. 23 Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466 (1785) ............................................................. 25 Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. -

Viewed by Most to Be the Act of Composing Music As It Is Being

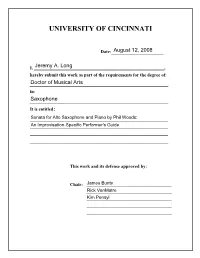

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods: An Improvisation-Specific Performer’s Guide A doctoral document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music By JEREMY LONG August, 2008 B.M., University of Kentucky, 1999 M.M., University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 2002 Committee Chair: Mr. James Bunte Copyright © 2008 by Jeremy Long All rights reserved ABSTRACT Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods combines Western classical and jazz traditions, including improvisation. A crossover work in this style creates unique challenges for the performer because it requires the person to have experience in both performance practices. The research on musical works in this style is limited. Furthermore, the research on the sections of improvisation found in this sonata is limited to general performance considerations. In my own study of this work, and due to the performance problems commonly associated with the improvisation sections, I found that there is a need for a more detailed analysis focusing on how to practice, develop, and perform the improvised solos in this sonata. This document, therefore, is a performer’s guide to the sections of improvisation found in the 1997 revised edition of Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods. -

Simone Dinnerstein, Piano Sat, Jan 30 Virtual Performance Simone Dinnerstein Piano

SIMONE DINNERSTEIN, PIANO SAT, JAN 30 VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE SIMONE DINNERSTEIN PIANO SAT, JAN 30 VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE PROGRAM Ich Ruf Zu Dir Frederico Busoni (1866-1924) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Three Chorales Johann Sebastian Bach Ich Ruf Zu Dir Richard Danielpour Frederico Busoni (1866-1924) | Johann Sebastian Bach, (1685-1750) (b, 1956) Les Barricades Mysterieuses François Couperin (1688-1733) Arabesque in C major, Op. 18 Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Mad Rush Philip Glass (b. 1937) Tic Toc Choc François Couperin BACH: “ICH RUF’ ZU DIR,” BWV 639 (ARR. BUSONI) Relatively early in his career, Bach worked in Weimar as the court organist. While serving in this capacity, he produced his Orgelbüchlein (little organ book): a collection of 46 chorale preludes. Each piece borrows a Lutheran hymn tune, set in long notes against a freer backdrop. “Ich ruf’ zu dir,” a general prayer for God’s grace, takes a particularly plaintive approach. The melody is presented with light ornamentation in the right hand, a flowing middle voice is carried by the left, and the organ’s pedals offer a steady walking bassline. The work is further colored by Bach’s uncommon choice of key, F Minor, which he tended to reserve for more wrought contrapuntal works. In this context, though, it lends a warmth to the original text’s supplication. In arranging the work for piano, around the year 1900, Busoni’s main challenge was to condense the original three-limbed texture to two. Not only did he manage to do this, while preserving the original pitches almost exactly, he found a way to imitate the organ’s timbral fullness.