Pine/Scrub Oak Sandhill (Blackjack Subtype)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Illinois Native Trees

Technical Forestry Bulletin · NRES-102 Checklist of Illinois Native Trees Jay C. Hayek, Extension Forestry Specialist Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences Updated May 2019 This Technical Forestry Bulletin serves as a checklist of Tree species prevalence (Table 2), or commonness, and Illinois native trees, both angiosperms (hardwoods) and gym- county distribution generally follows Iverson et al. (1989) and nosperms (conifers). Nearly every species listed in the fol- Mohlenbrock (2002). Additional sources of data with respect lowing tables† attains tree-sized stature, which is generally to species prevalence and county distribution include Mohlen- defined as having a(i) single stem with a trunk diameter brock and Ladd (1978), INHS (2011), and USDA’s The Plant Da- greater than or equal to 3 inches, measured at 4.5 feet above tabase (2012). ground level, (ii) well-defined crown of foliage, and(iii) total vertical height greater than or equal to 13 feet (Little 1979). Table 2. Species prevalence (Source: Iverson et al. 1989). Based on currently accepted nomenclature and excluding most minor varieties and all nothospecies, or hybrids, there Common — widely distributed with high abundance. are approximately 184± known native trees and tree-sized Occasional — common in localized patches. shrubs found in Illinois (Table 1). Uncommon — localized distribution or sparse. Rare — rarely found and sparse. Nomenclature used throughout this bulletin follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System —the ITIS data- Basic highlights of this tree checklist include the listing of 29 base utilizes real-time access to the most current and accept- native hawthorns (Crataegus), 21 native oaks (Quercus), 11 ed taxonomy based on scientific consensus. -

Guide to Plant Collection and Identification

GUIDE TO PLANT COLLECTION AND IDENTIFICATION by Jane M. Bowles PhD Originally prepared for a workshop in Plant Identification for the Ministry of Natural Resources in 1982. Edited and revised for the UWO Herbarium Workshop in Plant Collection and Identification, 2004 © Jane M. Bowles, 2004 -0- CHAPTER 1 THE NAMES OF PLANTS The history of plant nomenclature: Humans have always had a need to classify objects in the world about them. It is the only means they have of acquiring and passing on knowledge. The need to recognize and describe plants has always been especially important because of their use for food and medicinal purposes. The commonest, showiest or most useful plants were given common names, but usually these names varied from country to country and often from district to district. Scholars and herbalists knew the plants by a long, descriptive, Latin sentence. For example Cladonia rangiferina, the common "Reindeer Moss", was described as Muscus coralloides perforatum (The perforated, coral-like moss). Not only was this system unwieldy, but it too varied from user to user and with the use of the plant. In the late 16th century, Casper Bauhin devised a system of using just two names for each plant, but it was not universally adopted until the Swedish naturalist, Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) set about methodically classifying and naming the whole of the natural world. The names of plants: In 1753, Linnaeus published his "Species Plantarum". The modern names of nearly all plants date from this work or obey the conventions laid down in it. The scientific name for an organism consists of two words: i) the genus or generic name, ii) the specific epithet. -

Beneficial Trees for Wildlife Forestry and Plant Materials Technical Note

United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Technical Note No: TX-PM-16-01 August 2016 Beneficial Trees for Wildlife Forestry and Plant Materials Technical Note Background Trees provide shelter and food sources for a wide array of wildlife. White tail deer browse leaves and twigs along with acorns each fall and winter when other food sources are unavailable. More than 100 animal species eat acorns including rabbits, squirrels, wild hog, and gamebirds (Ober 2014). Songbirds and small mammals consume fruits and seeds. Wood peckers (Melanerpes sp.) and red tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicencis) nest in the cavities of hollow or dead trees (Dickson and Connor 1982). Butterflies, moths, and honeybees use trees as larval hosts, nectar sources, and shelter (Hill and Webster 1995). At right is a map illustrating forest types within the Western Gulf Coastal Plain. The Western Gulf Coastal Plain has a diversity of native hardwoods along with three species of southern pines (longleaf (Pinus palustris), shortleaf (Pinus echinata) and loblolly (Pinus taeda). Important native hardwoods used commercially and for wildlife include mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa), hackberry (Celtis laevigata), green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), black walnut (Juglans nigra), sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), black tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica), white oak (Quercus alba), southern red oak (Quercus falcata), water oak (Quercus nigra), willow oak (Quercus phellos), shumard oak (Quercus shumardii), post oak (Quercus stellata), bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and American elm (Ulmus americana) (Diggs 2006). 1 Purpose The purpose of this technical note is to assist conservation planners and land managers by providing basic tree establishment information and a list of beneficial wildlife trees (Table 1) when they are planning wildlife and pollinator habitat in east Texas, western Louisiana, southwestern Arkansas, and southeastern Oklahoma. -

Quercus ×Coutinhoi Samp. Discovered in Australia Charlie Buttigieg

XXX International Oaks The Journal of the International Oak Society …the hybrid oak that time forgot, oak-rod baskets, pros and cons of grafting… Issue No. 25/ 2014 / ISSN 1941-2061 1 International Oaks The Journal of the International Oak Society … the hybrid oak that time forgot, oak-rod baskets, pros and cons of grafting… Issue No. 25/ 2014 / ISSN 1941-2061 International Oak Society Officers and Board of Directors 2012-2015 Officers President Béatrice Chassé (France) Vice-President Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven (Belgium) Secretary Gert Fortgens (The Netherlands) Treasurer James E. Hitz (USA) Board of Directors Editorial Committee Membership Director Chairman Emily Griswold (USA) Béatrice Chassé Tour Director Members Shaun Haddock (France) Roderick Cameron International Oaks Allen Coombes Editor Béatrice Chassé Shaun Haddock Co-Editor Allen Coombes (Mexico) Eike Jablonski (Luxemburg) Oak News & Notes Ryan Russell Editor Ryan Russell (USA) Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven International Editor Roderick Cameron (Uruguay) Website Administrator Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven For contributions to International Oaks contact Béatrice Chassé [email protected] or [email protected] 0033553621353 Les Pouyouleix 24800 St.-Jory-de-Chalais France Author’s guidelines for submissions can be found at http://www.internationaloaksociety.org/content/author-guidelines-journal-ios © 2014 International Oak Society Text, figures, and photographs © of individual authors and photographers. Graphic design: Marie-Paule Thuaud / www.lecentrecreatifducoin.com Photos. Cover: Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven (Quercus macrocalyx Hickel & A. Camus); p. 6: Charles Snyers d’Attenhoven (Q. oxyodon Miq.); p. 7: Béatrice Chassé (Q. acerifolia (E.J. Palmer) Stoynoff & W. J. Hess); p. 9: Eike Jablonski (Q. ithaburensis subsp. -

IDENTIFYING OAKS: the HYBRID PROBLEM by Richard J

. IDENTIFYING OAKS: THE HYBRID PROBLEM by Richard J. Jensen I Anyone who has spent time trying to identify oaks (Quercus spp.), especially in the for ests of eastern North America, has encountered trees that defy classification into any of the recognized species. Such trees commonly are treated as putative hybrids and often are taken as evidence that species of oaks are not as discrete as species in other groups. On the other hand, some (e.g., Muller, 1941) have argued that many, if not most, putative hybrids are nothing more than stump sprouts or aberrant individuals of a species. Muller (1941) did not deny the existence of hybrids; he was cautioning against an inflated view of the frequency of hybridization as a result of cavalier claims. As he put it (Muller, 1951), 'The freedom of hybridization ascribed to oaks is immensely overrated." While I don't disagree with these sentiments, I do believe that hybrids are a common component of forests throughout North America. Virtually all oak species in North America have been claimed to produce hybrids with one or more related species. Hardin (1975j presented a diagram illustrating hybrid combina tions for the common white oak (Quercus alba L.) and Fig. 1 provides a similar view for northern red oak (Quercus rubra L.). Because these two species have very broad geo graphical ranges and come in contact with a large number of related taxa, there is ample opportunity for hybrid combina- RUB tions to arise naturally. These two examples also reflect the fact that MAR coc instances of hybridization are re stricted to taxa within a section: Quercus section Quercus (the white and chestnut oaks) and ELL IU Quercus section Lobatae (the red and black oaks), respectively. -

Ouachita Mountains Ecoregional Assessment December 2003

Ouachita Mountains Ecoregional Assessment December 2003 Ouachita Ecoregional Assessment Team Arkansas Field Office 601 North University Ave. Little Rock, AR 72205 Oklahoma Field Office 2727 East 21st Street Tulsa, OK 74114 Ouachita Mountains Ecoregional Assessment ii 12/2003 Table of Contents Ouachita Mountains Ecoregional Assessment............................................................................................................................i Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................................................iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..............................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................3 BACKGROUND ...........................................................................................................................4 Ecoregional Boundary Delineation.............................................................................................................................................4 Geology..........................................................................................................................................................................................5 Soils................................................................................................................................................................................................6 -

Quercus Laevis Walt. Turkey Oak Fagaceae Beech Family Richard F

Quercus laevis Walt. Turkey Oak Fagaceae Beech family Richard F. Harlow Turkey oak (Quercus Zaeuis), also called Catesby Habitat oak or scrub oak, is a small, moderately fast to fast- growing tree found on dry sandy soils of ridges, Native Range pinelands, and dunes, often in pure stands. This oak is not commercially important because of its size, but Turkey oak (figs. 1, 2) is limited to the dry the hard, close-grained wood is an excellent fuel. The pinelands and sandy ridges of the southeastern Coas- acorns are an important food to wildlife. Turkey oak tal Plain from southeast Virginia to central Florida is so named for its 3-lobed leaves which resemble a and west to southeast Louisiana (14). It reaches its turkey’s foot. maximum development in a subtropical climate. This Figure l-The native range of turkey oak. The author is Research Wildlife Biologist (retired), Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, Asheville, NC. 672 Quercus laevis in organic matter, and are strongly acid. Depth to water table is more than 152 cm (60 in) (18,211. Associated Forest Cover Turkey oak is commonly associated with longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), bluejack oak (Quercus in- cana), and sand (dwarf) post oak (Q. stellata var. margaretta). Depending on location it can also be associated with sand pine (Pinus clausa), laurel oak (Quercus laurifolia), southern red oak (Q. falcata), live oak (Q. virginiana), blackjack oak (Q. marilan- dica), sand hickory (Carya pallida), mockernut hick- ory (C. tomentosa), and black cherry (Prunus serotina). Understory, depending on the part of the range con- sidered, can include sassafras (Sassafras albidum), persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), pawpaw (Asimina spp.), dwarf huckleberry, deerberry, and tree sparkle- berry (Vaccinium spp.), New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus), gopher-apple (Geobalanus oblongifolius), blackberry (Rubus spp.), crooked wood (Lyonia spp.), scrub hickory (Carya fZoridana), myrtle oak (Quercus myrtifolia), Chapman oak (Q. -

June 2015 Hello Everyone. One Again We Had a Great Trip to Francis Marion National Forest

June 2015 Hello everyone. One again we had a great trip to Francis Marion National Forest. Just like last year, we combined our trip with the annual Hell Hole reptile and amphibian survey. SCAN members that participated include Phil Harpootlian, Kitty Beverly, Bill Hamel, Marsha and Bob Hamlin, Greg Ross, Pat and Jerry Bright, Gene Ott, Mary Douglass, Tom Jones, Kim McManus, Paul Kalbach, and Gordon Murphy. We all gathered at the primitive campground on Hell Hole Road. Win Ott did a quick show-and-tell with some of the snakes that he and Gene had already caught and gave us the opportunity to hold and photograph them. After Kim’s introduction to the various options for the day, which included road cruising for herps and exploring a nearby isolated wetland system, we split up and headed off in different directions. I can’t speak to the success that the road-cruisers had, but Kitty, Bill, and I headed for the wetland system. The isolated wetland was only a couple of miles from the campsite, as the crow flies, but it was quite a drive to get to it. Along the way we found an eastern kingsnake on the shoulder of Yellow Jacket Road. Once at the wetland, which was dominated by cypress and tupelo, we saw a few birds including a great blue heron and an anhinga. We only had a short time at the wetland because we wanted to get back to the campsite around noon to see some snakes that Jeff Holmes and his research staff had caught earlier in the week. -

2019 Oklahoma Native Plant Record

30 Oklahoma Native Plant Record Volume 19, December 2019 A WALK THROUGH THE McLOUD HIGH SCHOOL OAK-HICKORY FOREST WITH A CHECKLIST OF THE WOODY PLANTS Bruce A. Smith McLoud High School 1100 West Seikel McLoud, OK 74851 [email protected] ABSTRACT The McLoud High School oak-hickory forest is located a short distance from the McLoud High School campus. The forest has been used as an outdoor classroom for many years for high school students. This article will guide you through the forest trail and discuss several woody plants of interest at 16 landmarks. The article also includes a checklist of the 38 woody species identified in the forest. Key words: woody plants, checklist, invasive plants, hybridization, leaf curl INTRODUCTION indicated, all photos were taken by McLoud High School Botany classes over a number The McLoud High School forest has of years. been an important element in my teaching career for many years. I can’t remember the STUDY AREA first time that we started using the McLoud oak-hickory forest as an outdoor classroom. The forest is about 100 m (330 ft) by I do remember Kari Courkamp doing 76 m (250 ft) and is located near the research on tree lichens 25 years ago. Since McLoud High School campus in McLoud, that time there was a long period when we Oklahoma. It is bordered by adjacent used it mostly to learn about the forests on the south and east. The forest has composition and structure of the forest. In been utilized as an outdoor classroom for the last few years, we have done a variety of the high school students for many years. -

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

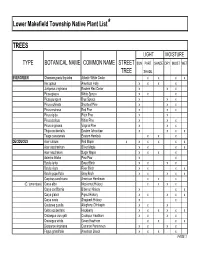

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

Tree Planting Cost-Share Program Guidelines

Tree Planting Cost-Share Program Guidelines The Town of Smithfield has lost many of its large canopy trees due to age, disease and storm damage. To that end, the Gwaltney Beautification Committee has unanimously voted to establish a tree planting cost-share program for the town with $5,000 allocated from the Julius Gwaltney Beautification Fund (JGBF) for FY 2009/2010. • Funds are available on a first come, first served basis as long as funds are available to any residential or business property owner within the Smithfield corporate limits on a 50/50 cost-share basis, with a maximum individual payment of $500. Participants must complete application, town staff or an appropriate representative of the Gwaltney Beautification Committee will review the proposed planting location, and applicant will receive written notification of approval prior to any purchase of tree(s). Work cannot proceed until the applicant is notified in writing of approval by town staff. Any unapproved requests or purchases will not be reimbursed. • Limit two (2) trees per address per program year. • Trees must be professionally installed and have a warranty of at least one (1) year. • Trees must be selected from the attached approved list of appropriate species and the planting site must be approved by town staff or an appropriate representative of the Gwaltney Beautification Committee. Preference is given to sites within public view. • Newly installed trees should be a minimum caliber of 1-1/2 inches, but not more than a 2 inch caliber. Participants must install mulch around the planting area. Mulch may be self- installed and is not eligible for reimbursement. -

An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks

Article An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks (Quercus Subgenus Quercus): Review of the Contribution of Phylogenomic Data to Biogeography and Species Diversity Paul S. Manos 1,* and Andrew L. Hipp 2 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, 330 Bio Sci Bldg, Durham, NC 27708, USA 2 The Morton Arboretum, Center for Tree Science, 4100 Illinois 53, Lisle, IL 60532, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The oak flora of North America north of Mexico is both phylogenetically diverse and species-rich, including 92 species placed in five sections of subgenus Quercus, the oak clade centered on the Americas. Despite phylogenetic and taxonomic progress on the genus over the past 45 years, classification of species at the subsectional level remains unchanged since the early treatments by WL Trelease, AA Camus, and CH Muller. In recent work, we used a RAD-seq based phylogeny including 250 species sampled from throughout the Americas and Eurasia to reconstruct the timing and biogeography of the North American oak radiation. This work demonstrates that the North American oak flora comprises mostly regional species radiations with limited phylogenetic affinities to Mexican clades, and two sister group connections to Eurasia. Using this framework, we describe the regional patterns of oak diversity within North America and formally classify 62 species into nine major North American subsections within sections Lobatae (the red oaks) and Quercus (the Citation: Manos, P.S.; Hipp, A.L. An Quercus Updated Infrageneric Classification white oaks), the two largest sections of subgenus . We also distill emerging evolutionary and of the North American Oaks (Quercus biogeographic patterns based on the impact of phylogenomic data on the systematics of multiple Subgenus Quercus): Review of the species complexes and instances of hybridization.