ICRC South Sudan Social Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of South Sudan "Establishment Order

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN "ESTABLISHMENT ORDER NUMBER 36/2015 FOR THE CREATION OF 28 STATES" IN THE DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Order 1 Preliminary Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. This order shall be cited as "the Establishment Order number 36/2015 AD" for the creation of new South Sudan states. 2. The Establishment Order shall come into force in thirty (30) working days from the date of signature by the President of the Republic. 3. Interpretation as per this Order: 3.1. "Establishment Order", means this Republican Order number 36/2015 AD under which the states of South Sudan are created. 3.2. "President" means the President of the Republic of South Sudan 3.3. "States" means the 28 states in the decentralized South Sudan as per the attached Map herewith which are established by this Order. 3.4. "Governor" means a governor of a state, for the time being, who shall be appointed by the President of the Republic until the permanent constitution is promulgated and elections are conducted. 3.5. "State constitution", means constitution of each state promulgated by an appointed state legislative assembly which shall conform to the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan 2011, amended 2015 until the permanent Constitution is promulgated under which the state constitutions shall conform to. 3.6. "State Legislative Assembly", means a legislative body, which for the time being, shall be appointed by the President and the same shall constitute itself into transitional state legislative assembly in the first sitting presided over by the most eldest person amongst the members and elect its speaker and deputy speaker among its members. -

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map Kebkabiya El Fashir Abyad Bara Umm Dam El Kawa Ermil Nahl Doka Umm Bel Sennar Tawila Dirra Umm El Hilla Iyal Es Suki El Hawata Keddada Mahbub El Obeid Rabak Jebel Shangil Tobay Wad Banda Dud Singa Gallabat Wada`ah Umm Rawaba En Nahud El Rahad Higar Galegu El Jebelein Kas Taweisha S U D A N El Abbasiya Nyala Dilling Kortala Dangur El Odaiya Geigar Sharafa Delami Ed Damazin Rashad Renk e l El Barun Ed Da`ein i El Lagowa Abu Jibaiha Edd El Fursan N Babanusa e Heiban t Abu Abu i Bau Guba Ragag h Matariq Kulshabi Bikori Gabra W El Muglad Kadugli Kologi Keili Mumallah Umm Ulu Buram Keilak Talodi Barbit Wadega Belfodiyo Qardud Kaka Paloich Tungaru Junguls Asosa Radom Riangnom Sumeih El Melemm Oriny Kodok Mendi Boing Bambesi Hofrat Naam Fagwir Aboke en Nahas Malakal Nejo Abyei UPPER NILE Daga Bentiu Gimbi Bai War-awar Fangak Malwal Post Kafia Pan Nyal Mayom Kingi Malualkon Abwong Wang Kai Fagwir Kan Sobat Banyjiel Gidami Sadi Aweil Wun Rog Yubdo Gossinga UNITY Gumbiel Nasser NORTHERN Gogrial Nyerol Malek Thul Raga BAHR Akop Leer Mogogh Biel Bure Metu Wun Gambela EL GHAZAL WARRAP Ayod Waat Abay Gore Kwajok Shwai Adok Atiedo Warrap Fathai Faddoi Jonglei Canal Tor Deim Zubeir Madeir E T H I O P I A Bisellia Bir Di Duk Fadiat Akobo WESTERN Wau Gech`a Lol Mbili Duk Kongettit Les Trois BAHR Wakela Atum Faiwil Tepi Riviêres EL GHAZAL Tonj Shambe Peper Pochalla LAKES Kongor C E N T R A L Bo River Post Rafili Giamciar Teferi Rumbek Lau Akelo Palwal Jonglei JONGLEI Pibor A F R I C A N Ubori Akot Pibor Yirol Kantiere R E P U -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

Humanitarian Response Plan South Sudan

HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2021 RESPONSE PLAN ISSUED MARCH 2021 SOUTH SUDAN 01 About This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. The Humanitarian Response Plan is a presentation of the coordinated, strategic response devised by humanitarian agencies in order to meet the acute needs of people affected by the crisis. It is based on, and responds to, evidence of needs described in the Humanitarian Needs Overview. Manyo Renk Renk SUDAN Kaka Melut Melut Maban Fashoda Riangnhom Bunj Oriny UPPER NILE Abyei region Pariang Panyikang Malakal Abiemnhom Tonga Malakal Baliet Aweil East Abiemnom Rubkona Aweil North Guit Baliet Dajo Gok-Machar War-Awar Twic Mayom Atar 2 Longochuk Bentiu Guit Mayom Old Fangak Aweil West Turalei Canal/Pigi Gogrial East Fangak Aweil Gogrial Luakpiny/Nasir Maiwut Aweil West UNITY Yomding Raja NORTHERN South Gogrial Koch Nyirol Nasir Maiwut Raja BAHR EL Bar Mayen Koch Ulang Kuajok WARRAP Leer Lunyaker Ayod GHAAL Tonj North Mayendit Ayod Aweil Centre Waat Mayendit Leer Uror Warrap Romic ETHIOPIA Yuai Tonj East WESTERN BAHR Nyal Duk Fadiat Akobo Wau Maper JONGLEI CENTRAL EL GHAAL Panyijiar Duk Akobo Kuajiena Rumbek North AFRICAN Wau Tonj Pochalla Jur River Cueibet REPUBLIC Tonj Rumbek Kongor Pochala South Cueibet Centre Yirol East Twic East Rumbek Adior Pibor Rumbek East Nagero Wullu Akot Yirol Bor South Tambura Yirol West Nagero LAKES Awerial Pibor Bor Boma Wulu Mvolo Awerial Mvolo Tambura Terekeka Kapoeta International boundary WESTERN Terekeka North Mundri -

Civil Affairs Summary Action Report (01 March-20 April 2018)

Civil Affairs Division Reporting Period: 01 March– 20 April 2018 Greater Bahr el Ghazal Actions Sports for peace, Raja, Lol State, 14-16 April Context: The creation of Lol State under the 28 state model, carved out of the areas that were formerly part of Northern and Western Bahr el Ghazal states, has been a source of polarized relations between Fertit and Dinka Malual communities. The Fertit opposed the formation of the new state on the basis that they would be marginalized by the larger Dinka Ma- 7 lual population. 4 Action: Recognizing the significant role youth play in communal con- flict and the importance of leveraging their role toward improved social relations, CAD Aweil FO in partnership with the Lol State Ministry of Information, Culture, Youth and Sports, organised a two-day football tour- nament in Raja, Lol State, to facilitate communal linkages and promote 2 coexistence between Fertit and Dinka Malual. The event featured the par- ticipation of over 60 Fertit youth from Raja, and Dinka Malual youth from Aweil North County (10 women participated). The Acting Governor, Speaker of State Legislative Assembly, Minister of Information, Culture community of NBeG held separate pre-migration conferences with Misser- and Youth, Minister of Education and SPLM commander of the area also iya and Rezeigat pastoralists from Sudan in Wanyjok, Aweil East, and attended the event and urged peaceful coexistence. Nymlal, Lol State, respectively. In both conferences, they reached a num- Impact: The participants expressed hope that the event will open ave- ber of resolutions, which are recognized as binding on the communities. -

National Education Statistics

2016 NATIONAL EDUCATION STATISTICS FOR THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN FEBRUARY 2017 www.goss.org © Ministry of General Education & Instruction 2017 Photo Courtesy of UNICEF This publication may be used as a part or as a whole, provided that the MoGEI is acknowledged as the source of information. The map used in this document is not the official maps of the Republic of South Sudan and are for illustrative purposes only. This publication has been produced with financial assistance from the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) and technical assistance from Altai Consulting. Soft copies of the complete National and State Education Statistic Booklets, along with the EMIS baseline list of schools and related documents, can be accessed and downloaded at: www.southsudanemis.org. For inquiries or requests, please use the following contact information: George Mogga / Director of Planning and Budgeting / MoGEI [email protected] Giir Mabior Cyerdit / EMIS Manager / MoGEI [email protected] Data & Statistics Unit / MoGEI [email protected] Nor Shirin Md. Mokhtar / Chief of Education / UNICEF [email protected] Akshay Sinha / Education Officer / UNICEF [email protected] Daniel Skillings / Project Director / Altai Consulting [email protected] Philibert de Mercey / Senior Methodologist / Altai Consulting [email protected] FOREWORD On behalf of the Ministry of General Education and Instruction (MoGEI), I am delighted to present The National Education Statistics Booklet, 2016, of the Republic of South Sudan (RSS). It is the 9th in a series of publications initiated in 2006, with only one interruption in 2014, a significant achievement for a new nation like South Sudan. The purpose of the booklet is to provide a detailed compilation of statistical information covering key indicators of South Sudan’s education sector, from ECDE to Higher Education. -

HATE SPEECH MONITORING and CONFLICT ANALYSIS in SOUTH SUDAN Report #5: September 24 – October 9, 2017

October 12, 2017 HATE SPEECH MONITORING AND CONFLICT ANALYSIS IN SOUTH SUDAN Report #5: September 24 – October 9, 2017 This report is part of a broader initiative by PeaceTech Lab to analyze online hate speech in South Sudan in order to help mitigate the threat of hateful language in fueling violence on-the-ground. Hate speech can be defined as language that can incite others to discriminate or act against individuals or groups based on their ethnic, religious, racial, gender or national identity. The Lab also acknowledges the role of “dangerous speech,” which is a heightened form of hate speech that can catalyze mass violence. Summary of Recent Events his reporting period is highlighted by developments on both diplomatic and military fronts. In terms of diplomatic efforts, IGAD’s release of the T revitalization forum timetable put forward an October 13-17 period for consultations with South Sudanese leaders and citizens on the peace process. Consistent with this timeline, IGAD foreign ministers have begun their consultations with opposition leaders. On October 5, Sudanese Foreign Minister Ibrahim Ghandour and Ethiopian Foreign Minister Workneh Gebeyhu met with former first vice president Riek Machar in South Africa, and on October 9, Ghandour and IGAD Special Envoy Ismail Wais met with National Democratic Movement (NDM) leader Lam Akol in Khartoum. Meanwhile, new online narratives are forming around these discussions. The approach adopted by IGAD includes consulting with various stakeholders as individual groups, instead of an all-inclusive conference. While some factions welcome this approach, others, such as Taban’s SPLA-IO wing, oppose it. -

Tracking the Flow of Government Transfers Financing Local Government Service Delivery in South Sudan

Tracking the flow of Government transfers Financing local government service delivery in South Sudan 1.0 Introduction The Government of South Sudan through its Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MoFEP) makes transfers of funds to states and local governments on a monthly basis to finance service delivery. Broadly speaking, the government makes five types of transfers to the local government level: a) Conditional salary transfers: these funds are transferred to be used by the county departments of education, health and water to pay for the salaries of primary school teachers, health workers and water sector workers respectively. b) Operation transfers for county service departments: these funds are transferred to the counties for the departments of education, health and water to cater for the operation costs of these county departments. c) County block transfer: each county receives a discretionary amount which it can spend as it wishes on activities of the county. d) Operation transfer to service delivery units (SDUs): these funds are transferred to primary schools and primary health care facilities under the jurisdiction of each county to cater for operation costs of these units. e) County development grant (CDG): the national annual budget includes an item to be transferred to each county to enable the county conduct development activities such as construction of schools and office blocks; in practice however this money has not been released to the counties since 2011 mainly due to a lack of funds. 2.0 Transfer and spending modalities/guidelines Funds are transferred by the national Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning from the government accounts at Bank of South Sudan to the respective state’s bank accounts through the state ministries of Finance (SMoF). -

Security Responses in Jonglei State in the Aftermath of Inter-Ethnic Violence

Security responses in Jonglei State in the aftermath of inter-ethnic violence By Richard B. Rands and Dr. Matthew LeRiche Saferworld February 2012 1 Contents List of acronyms 1. Introduction and key findings 2. The current situation: inter-ethnic conflict in Jonglei 3. Security responses 4. Providing an effective response: the challenges facing the security forces in South Sudan 5. Support from UNMISS and other significant international actors 6. Conclusion List of Acronyms CID Criminal Intelligence Division CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement CRPB Conflict Reduction and Peace Building GHQ General Headquarters GoRSS Government of the Republic of South Sudan ICG International Crisis Group MSF Medecins Sans Frontières MI Military Intelligence NISS National Intelligence and Security Service NSS National Security Service SPLA Sudan People’s Liberation Army SPLM Sudan People’s Liberation Movement SRSG Special Representative of the Secretary General SSP South Sudanese Pounds SSPS South Sudan Police Service SSR Security Sector Reform UNMISS United Nations Mission in South Sudan UYMPDA Upper Nile Youth Mobilization for Peace and Development Agency Acknowledgements This paper was written by Richard B. Rands and Dr Matthew LeRiche. The authors would like to thank Jessica Hayes for her invaluable contribution as research assistant to this paper. The paper was reviewed and edited by Sara Skinner and Hesta Groenewald (Saferworld). Opinions expressed in the paper are those of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of Saferworld. Saferworld is grateful for the funding provided to its South Sudan programme by the UK Department for International Development (DfID) through its South Sudan Peace Fund and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) through its Global Peace and Security Fund. -

South Sudan Human Rights Monitor

SOUTH SUDAN HUMAN RIGHTS MONITOR February 1, 2018 to May 31, 2018 This report is based on the work of internationally trained local monitors on the ground in South Sudan working for a national human rights organization. Both these monitors and the organization must remain anonymous given present security concerns. The information reported herein meets the threshold for initiating an investigation. There is a reasonable basis to believe that the following incidents occurred. I. INTRODUCTION South Sudan has experienced widespread human rights abuses and a plethora of crimes, including a significant amount of sexual and gender-based and ethnic violence, since the outbreak of the conflict in December 2013. Since the start of the conflict, violence has escalated at an alarming rate across the country, resulting in widespread killings, rapes, extensive property damage and looting of civilian property. This report details 19 incidents of human rights abuses and crimes committed against civilians that have been documented by local monitors working anonymously in multiple locations around the country. The gross human rights violations and crimes included in this report illustrate the severity of the conflict and its overall impact on the lives of civilians, including damaging their ability to sustain their livelihoods, and the destruction of the social fabric of their communities that will affect generations of South Sudanese. While this report does not cover the totality of human rights abuses and crimes that have occurred in South Sudan during the reporting period, it does provide a reasonable basis to believe that these human rights abuses and crimes have occurred as reported and a clear basis for analysis and human rights advocacy. -

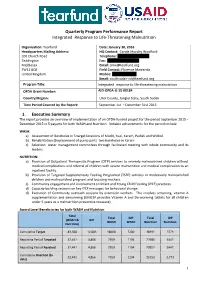

Quarterly Program Performance Report Integrated Response to Life-Threatening Malnutrition 1. Executive Summary

Quarterly Program Performance Report Integrated Response to Life-Threatening Malnutrition Organisation: Tearfund Date: January 30, 2016 Headquarters Mailing Address: HQ Contact: Carole Murphy Woolford 100 Church Road Telephone: +44 (0) 20 8943 7902 Teddington Fax: +44 (0) 20 8943 3594 Middlesex Email: [email protected] TW11 8QE Field Contact: Florence Mawanda United Kingdom Mobile: +211913521243 Email: [email protected] Program Title: Integrated response to life-threatening malnutrition OFDA Grant Number: AID-OFDA-G-15-00184 Country/Region: Uror County, Jonglei State, South Sudan Time Period Covered by the Report: September 1st – December 31st 2015 1. Executive Summary The report provides an overview of implementation of an OFDA-funded project for the period September 2015 – December 2015 in 5 payams for both WASH and Nutrition. Notable achievements for the period include: WASH: a) Assessment of Boreholes in 5 target locations of Modit, Yuai, Karam, Padiek and Wickol. b) Rehabilitation ((replacement of pump parts two boreholes in Karam c) Selection water management committees through facilitated meeting with whole community and its leaders NUTRITION: a) Provision of Outpatient Therapeutic Program (OTP) services to severely malnourished children without medical complications and referral of children with severe malnutrition and medical complication to an inpatient facility. b) Provision of Targeted Supplementary Feeding Programed (TSFP) services to moderately malnourished children and malnourished pregnant and lactating mothers. c) Community engagement and involvement on Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) practices. d) Capacity building sessions on key IYCF messages for behavioral change. d) Execution of Community outreach sessions by extension workers. This involves screening, vitamin A supplementation and deworming (UNICEF provides Vitamin A and De-worming tablets for all children under 5 years as a malnutrition preventive measure).