New 'Freedom' and Its Old 'Enemies'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES and the LANGUAGE of POLITICS in LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(L921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT and REACTION

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(l921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL BY KOUSHIKIDASGUPTA ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF GOUR BANGA MALDA UPERVISOR PROFESSOR I. SARKAR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL RAJA RAMMOHANPUR, DARJEELING WEST BENGAL 2011 IK 35 229^ I ^ pro 'J"^') 2?557i UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL Raja Rammohunpur P.O. North Bengal University Dist. Darjeeling - 734013 West Bengal (India) • Phone : 0353 - 2776351 Ref. No Date y.hU. CERTIFICATE OF GUIDE AND SUPERVISOR Certified that the Ph.D. thesis prepared by Koushiki Dasgupta on Minor Political Parties and the Language of Politics in Late Colonial Bengal ^921-194'^ J Attitude, Adjustment and Reaction embodies the result of her original study and investigation under my supervision. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this study is the first of its kind and is in no way a reproduction of any other research work. Dr.LSarkar ^''^ Professor of History Department of History University of North Bengal Darje^ingy^A^iCst^^a^r Department of History University nfVi,rth Bengal Darjeeliny l\V Bj DECLARATION I do hereby declare that the thesis entitled MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL (l921- 1947); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION being submitted to the University of North Bengal in partial fulfillment for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in History is an original piece of research work done by me and has not been published or submitted elsewhere for any other degree in full or part of it. -

Freedom in West Bengal Revised

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Freedom and its Enemies: Politics of Transition in West Bengal, 1947-1949 * Sekhar Bandyopadhyay Victoria University of Wellington I The fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence became an occasion for the publication of a huge body of literature on post-colonial India. Understandably, the discussion of 1947 in this literature is largely focussed on Partition—its memories and its long-term effects on the nation. 1 Earlier studies on Partition looked at the ‘event’ as a part of the grand narrative of the formation of two nation-states in the subcontinent; but in recent times the historians’ gaze has shifted to what Gyanendra Pandey has described as ‘a history of the lives and experiences of the people who lived through that time’. 2 So far as Bengal is concerned, such experiences have been analysed in two subsets, i.e., the experience of the borderland, and the experience of the refugees. As the surgical knife of Sir Cyril Ratcliffe was hastily and erratically drawn across Bengal, it created an international boundary that was seriously flawed and which brutally disrupted the life and livelihood of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis, many of whom suddenly found themselves living in what they conceived of as ‘enemy’ territory. Even those who ended up on the ‘right’ side of the border, like the Hindus in Murshidabad and Nadia, were apprehensive that they might be sacrificed and exchanged for the Hindus in Khulna who were caught up on the wrong side and vehemently demanded to cross over. -

Azad Hind Fauj and Provisional Government : a Saga of Netaji Prof

Orissa Review * August - 2004 Azad Hind Fauj and Provisional Government : A Saga of Netaji Prof. Jagannath Mohanty "I have said that today is the proudest day of fact one of his greatest speeches which my life. For enslaved people, there can be no overwhelmed the entire contingents of Indian greater pride, no higher honour, than to be the National Army (INA) gathered there under the first soldier in the army of liberation. But this scorching tropical sun of Singapore. There was honour carries with it a corresponding a rally of 13,000 men drawn from the people responsibility and I am deeply of South-East Asian countries. conscious of it. I assure you Then Netaji toured in Thailand, that I shall be with you in Malay, Burma, Indo-China and darkness and in sunshine, in some other countries and sorrows and in joy, in suffering inspired the civilians to join the and in victory. For the present, army and mobilised public I can offer you nothing except opinion for recruitment of hunger, thirst, privation, forced soldiers, augmenting resources marches and deaths. But if you and establishing new branches follow me in life and in death of Indian National Army. He - as I am confident you will - I promised the people that he shall lead you to victory and would open the second war of freedom. It does not matter Independence and set up a who among us will live to see provisional Government of India free. It is enough that Free India under whose banner India shall be free and that we shall give our three million Indians of South-East Asia would all to make her free. -

Criminal Investigation Department Govt

a -. !h ii Criminal Investigation Department Govt. of West Bengal. Bhabani Bh aban, Alipore, Kolkata - 700.027.. "Tender for purchase of "Photographic Materials" of clD, west Bengal for the financial year 2015-16." Tender Year .201 5 - 2010. Tender Notice No. : 051 2015-10 /ClD /WB. closinq Date : 7 (seven) days after publication. rENpqF NorlqE The Criminal Investigation Department, West Bengal, Bhabani Bhawan, Alipore, Kolkata - 700027 , invites sealed Tenders from private firms for purchase Photography materials of ClD, West Bengal. l. SPECIFICATION OF ITEMS :- Photographic materials for CID, West Bengal. (Details list may be collected by the bidders from O/S, Police Office, CID. West Bengal or CID Website, www.cidwestbengal.gov.in.) 2. SCHEDULE:- A' Closing and Opening Date: 7 (Seven) days after publications Time 14.00 hrs. 3. SU.BMISSION OF BID :- I. Bidders may collect / download the Tender document from CID Website, www.cidwestbengal.eov.in. The bidders may remain present at the time of opening of tenders. il. Prices quoted, shall be including all taxes not to be exceed MRp. The quotations should be submitted in envelopes duly sealed and properly super scribed with name and address of the firms and "Tender No- 05l}0l5- l6/CID/WB and Tenders from private firms for purchase of "Photographic materials" It must be addressed to the ADG, cID, west Bengal, Bhabani Bhawan, Alipore, Kolkata-700027, and must be sent to this office on or before the closing time for submission of tenders. In case the quotations are received without sealed cover, the tender will be liable to be cancelled. -

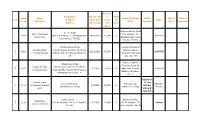

Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application (Receving) Basic Pay / Pay in Pay Band Type

Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. Name Name & Address Roster Date of Date of Sl. No. & Office Application Pay in of Status Sl. No S/D/W/O D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address (Receving) Pay Flat Band Accounts Officer, 9D & Gr. - II Sister Smt. Anita Biswas B.G. Hospital , 57, 1 1879 9D & B.G. Hospital , 57, Beleghata Main 28/12/2012 21,140 A ALLOTTED Sri Salil Dey Beleghata Main Road, Road, Kolkata - 700 010 Kolkata - 700 010 District Fishery Officer Assistant Director of Bikash Mandal O/O the Deputy Director of Fisheries, Fisheries, Kolkata 2 1891 31/12/2012 22,500 A ALLOTTED Lt. Joydev Mandal Kolkata Zone, 9A, Esplanade East, Kol - Zone, 9A, Esplanade 69 East , Kol - 69 Asstt. Director of Fishery Extn. Officer Fisheries, South 24 Swapan Kr. Saha O/O The Asstt. Director of Fisheries 3 1907 1/1/2013 17,020 A Pgns. New Treasury ALLOTTED Lt. Basanta Saha South 24 Pgs., Alipore, New Treasury Building (6th Floor), Building (6th Floor), Kol - 27 Kol - 27 Eligible for Samapti Garai 'A' Type Assistant Professor Principal, Lady Allotted '' 4 1915 Sri Narayan Chandra 2/1/2013 20,970 A flats but Lady Brabourne College Brabourne College B'' Type Garai willing 'B' Type Flat Staff Nurse Gr. - II Accounts Officer, Lipika Saha 5 1930 S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, A.J.C. Bose Rd. , 4/1/2013 16,380 A S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, Allotted Sanjit Kumar Saha Kol -20 A.J.C. Bose Rd. , Kol -20 Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. -

CID West Bengal

Registered No. C_603 No. – 09 of 2017 CID West Bengal Criminal Intelligence Gazette Property of the Government of West Bengal Published by Authority. Kolkata September - 2017 BS - 1424 Part - I Special Notice: Nil Part – II (A) Persons wanted in specific cases: - Reference:- Bhaktinagar PS Case No. 1444/15 dated 13.10.15 u/s 20(b)(ii)(c)/23/25 NDPS Act. Shown beside the picture of the following accused person namely Shyam Limbu s/o Som Bahadur Limbu of village Shanti Nagar, PS Bhudwara, District Jhapa, Nepal was convicted in c/w the above 1. noted case. The accused person escaped from Sadar Court Hazat Jalpaiguri on 15.9.17. D/R Age approx 27 years, Ht. 5’-3”, complexion fair, built slim, two mole on his right side of the bally. All concerned are requested if any information found about the accused person please contact to the Superintendent of Jalpaiguri central correctional home and superintendent of Police Jalpaiguri. Reference:- Madanriting PS Case No. 79/(8)2017 u/s 3/4/5/6 prevention of immoral trafficking Act r/w section 3(a)/4/17 of POCSO Act. 2. Shown beside the picture of the following accused person namely Samir Dey s/o not noted of East Khasi hills, Shillong is wanted in c/w the above noted case. All concerned are requested if any information found about the accused person please contact to the Superintendent of Police East Khasi hills, Shillong. (B) Persons arrested who may be wanted elsewhere: - Nil. 2 (C) (i) Important arrest and property found in the possession of arrested persons with reference to NDPS Act :- Sl. -

Chapter 5 an Overview of Medinipur District

Chapter 5 An overview of Medinipur District CHAPTER 5 AN OVERVIEW OF MEDINIPUR DISTRICT 5.1 BACKGROUND Undivided Medinipur was the biggest district in the area (22°57’10’’N to 21°36’35’’N and 88°12’40’’E to 86°33’50’’E) of West Bengal (“Brief Industrial”). Census report 2011, reveals Medinipur district as having an area of 9,368 sq. km. and the population is 59,13,457 where 3,007,885 males and 2,905,572 females (“Paschim Medinipur”). The famous Chinese traveller Fa-hien and Hiuen Tsang visited Tamralipta (modern Tamluk). Midnapore town became the headquarters of Medinipur district which became famous for the struggle of independence against the British Administration (“District Census” 9). The district was divided into Paschim Medinipur and Purba Medinipur on 1st January, 2002 (“Brief Industrial”). The district of Paschim Medinipur is situated in the extension of Chota Nagpur plateau gradually sloping towards East and South (“District Human” 5). South-eastern railway track from Howrah to Adra runs through this district and also state highway no. 60 runs parallel to the railway track. The national highway no. 6 (Bombay road) also runs through this district. The western part of this south-eastern railway track in Paschim Medinipur is infertile laterite rocks and mostly laterite soil whereas the eastern part is fertile alluvial. The district of Paschim Medinipur has 3 Subdivisions, namely i) Ghatal ii) Kharagpur iii) Midnapore Sadar (“District Census” 20), 21 Blocks, 21 Panchayat Samity, 1 Zilla Parishad, 15 Members of the Legislative Assembly and 2 Members of Parliament (“Panchayat and R. -

Census of India 1941, Bengal, Table Part II India

- ---------------_-----_ ---- -:- , ------- fq~~ ~G(R ~ ~l~ 'revio"'u~ References Later Referei:lces I-AREA, HOUSES AND POPULATION This table,borresponds to Imperial Table I of 1931 and shows for divisions, dIstricts and states the t.Tea, the num}{er of houses and inhabited rural mauzas, and the distribution of occupied houses and popula tion between Jural and urban areas. Similar-details for subdivisions ?>nd police-stations are shown in Pro- vincial TablE} L . 2. ThejGtl'e,as given differ in some cases from those given is the corresponding tab~ of· Hl31. "They are based on tl,1e figures supplied by the Government of Bengal. The province gained duriVg the decade an area of 18114' sq miles as a net result of transfers between Bengal, Bihar, Orissa and A$arn, th-e- details of which #e 'given below :- Area gained by transfer Area lost by transfer Districts of Bengal ...A.... __~-, ,--- --...A....--__----. Net gain to Frain .Area in To Area in Bengal sq miles sq miles 1 2 3 4 5 6 All Districts Bihar 18·92 Bihar, Orissa & Assam 0,713 +18·14 Midnapore Mayurbhanj (Orissa) 0·25 -0·25 Murshidabad ., Santhal Parganas (Bihar) 0·13 -0·13 Rangpur Goalpara (Assam) 0·40 -0·40 lV!alda .. ., Santhal Parganas +16·72 (Bihar) Dinajpur .. Purnea (Bihar) 2·20 +2·20 Details of the population. at each census in the areas affected by tbese inter-provincial transfers are given in the title page to Imperial Table II. 3. Detailed particulars of the areas treated as towns and of the variation in their numbers since 1931 .are given in Imperial Tftble V and Provincial Table I. -

The Indian Police Journal Vol

Vol. 63 No. 2-3 ISSN 0537-2429 April-September, 2016 The Indian Police Journal Vol. 63 • No. 2-3 • April-Septermber, 2016 BOARD OF REVIEWERS 1. Shri R.K. Raghavan, IPS(Retd.) 13. Prof. Ajay Kumar Jain Former Director, CBI B-1, Scholar Building, Management Development Institute, Mehrauli Road, 2. Shri. P.M. Nair Sukrali Chair Prof. TISS, Mumbai 14. Shri Balwinder Singh 3. Shri Vijay Raghawan Former Special Director, CBI Prof. TISS, Mumbai Former Secretary, CVC 4. Shri N. Ramachandran 15. Shri Nand Kumar Saravade President, Indian Police Foundation. CEO, Data Security Council of India New Delhi-110017 16. Shri M.L. Sharma 5. Prof. (Dr.) Arvind Verma Former Director, CBI Dept. of Criminal Justice, Indiana University, 17. Shri S. Balaji Bloomington, IN 47405 USA Former Spl. DG, NIA 6. Dr. Trinath Mishra, IPS(Retd.) 18. Prof. N. Bala Krishnan Ex. Director, CBI Hony. Professor Ex. DG, CRPF, Ex. DG, CISF Super Computer Education Research Centre, Indian Institute of Science, 7. Prof. V.S. Mani Bengaluru Former Prof. JNU 19. Dr. Lalji Singh 8. Shri Rakesh Jaruhar MD, Genome Foundation, Former Spl. DG, CRPF Hyderabad-500003 20. Shri R.C. Arora 9. Shri Salim Ali DG(Retd.) Former Director (R&D), Former Spl. Director, CBI BPR&D 10. Shri Sanjay Singh, IPS 21. Prof. Upneet Lalli IGP-I, CID, West Bengal Dy. Director, RICA, Chandigarh 11. Dr. K.P.C. Gandhi 22. Prof. (Retd.) B.K. Nagla Director of AP Forensic Science Labs Former Professor 12. Dr. J.R. Gaur, 23 Dr. A.K. Saxena Former Director, FSL, Shimla (H.P.) Former Prof. -

Journal of History

Vol-I. ' ",', " .1996-97 • /1 'I;:'" " : ",. I ; \ '> VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Journal of History S.C.Mukllopadhyay Editor-in-Chief ~artment of History Vidyasagar University Midnapore-721102 West Bengal : India --------------~ ------------ ---.........------ I I j:;;..blished in June,1997 ©Vidyasagar University Copyright in articles rests with respective authors Edi10rial Board ::::.C.Mukhopadhyay Editor-in-Chief K.K.Chaudhuri Managing Editor G.C.Roy Member Sham ita Sarkar Member Arabinda Samanta Member Advisory Board • Prof.Sumit Sarkar (Delhi University) 1 Prof. Zahiruddin Malik (Aligarh Muslim University) .. <'Jut". Premanshu Bandyopadhyay (Calcutta University) . hof. Basudeb Chatterjee (Netaji institute for Asian Studies) "hof. Bhaskar Chatterjee (Burdwan University) Prof. B.K. Roy (L.N. Mithila University, Darbhanga) r Prof. K.S. Behera (Utkal University) } Prof. AF. Salauddin Ahmed (Dacca University) Prof. Mahammad Shafi (Rajshahi University) Price Rs. 25. 00 Published by Dr. K.K. Das, Registrar, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore· 721102, W. Bengal, India, and Printed by N. B. Laser Writer, p. 51 Saratpalli, Midnapore. (ii) ..., -~- ._----~~------ ---------------------------- \ \ i ~ditorial (v) Our contributors (vi) 1-KK.Chaudhuri, 'Itlhasa' in Early India :Towards an Understanding in Concepts 1 2.Bhaskar Chatterjee, Early Maritime History of the Kalingas 10 3.Animesh Kanti Pal, In Search of Ancient Tamralipta 16 4.Mahammad Shafi, Lost Fortune of Dacca in the 18th. Century 21 5.Sudipta Mukherjee (Chakraborty), Insurrection of Barabhum -

Cijhar 22 FINAL.Pmd

1 1 Vijayanagara as Reflected Through its Numismatics *Dr. N.C. Sujatha Abstract Vijayanagara an out-and-out an economic state which ushered broad outlay of trade and commerce, production and manufacture for over- seas markets. Its coinage had played definitely a greater role in tremendous economic activity that went on not just in India, but also across the continent. Its cities were bustled with traders and merchandise for several countries of Europe and Africa. The soundness of their economy depended on a stable currency system. The present paper discusses the aspects relating to the coinage of Vijayanagara Empire and we could enumerate from these coins about their administration. Its currency system is a wonderful source for the study of its over-all activities of administration, social needs, religious preferences, vibrant trade and commerce and traditional agriculture and irrigation Key words : Empire, Administration, Numismatics, Currency, trade, commerce, routes, revenue, land-grants, mint, commercial, brisk, travellers, aesthetic, fineness, abundant, flourishing, gadyana, Kasu, Varaha, Honnu, panam, Pardai, enforcement, Foundation of Vijayanagara Empire in a.d.1336 is an epoch in the History of South India. It was one of the great empires founded and ruled for three hundred years, and was widely extended over peninsular India. It stood as a bulwark against the recurring invasions from the Northern India. The rule Vijayanagara is the most enthralling period for military exploits, daring conquests, spread of a sound administration. Numismatics is an important source for the study of history. At any given time, the coins in circulation can throw lot of light on then prevalent situation. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies.