Journal of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financial Year

GITANJALI GEMS LIMITED Statement Showing Unpaid / Unclaimed Dividend as on Annual General Meeting held on September 28, 2012 for the financial year 2011‐12 First Name Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of Securities Due(in of transfer to Rs.) IEPF (DD‐MON‐ YYYY) JYOTSANA OPP SOMESHWAR PART 3 NEAR GULAB TOWER THALTEJ AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT AHMEDABAD 380054 GGL0038799 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 105.00 08‐OCT‐2019 MANISH BRAHMBHAT 16 MADHUVAN BUNGLOW UTKHANTHESWAR MAHADEV RD AT DEGHAM DIST GANDHINAGAR DEHGAM INDIA GUJARAT GANDHI NAGAR 382305 GGL0124586 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 105.00 08‐OCT‐2019 BHARAT PATEL A‐8 SHIV PARK SOC NR RAMROY NAGAR N H NO 8 AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT GANDHI NAGAR 382415 GGL0041816 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 105.00 08‐OCT‐2019 SHARMISTA GANDHI 13 SURYADARSHAN SOC KARELIBAUG VADODARA INDIA GUJARAT VADODARA 390228 GGL0048293 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 105.00 08‐OCT‐2019 C MALPANI SURAT SURAT INDIA GUJARAT SURAT 395002 GGL0049550 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 105.00 08‐OCT‐2019 SONAL SHETH C/O CENTURION BANK CENTRAL BOMBAY INFOTECH PARK GR FLR 101 K KHADEVE MARG MAHALAXMI MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400011 GGL0057531 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 105.00 08‐OCT‐2019 CHIRAG SHAH C/O CENTURION BNK CENTRAL BOMY INFOTECH PARK GR FLR 101 KHADVE MAWRG MAHALAXMI MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400011 GGL0057921 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 105.00 08‐OCT‐2019 NUPUR C/O -

The Bihar and West Bengal (Transfer of Territories) Act, 1956 ______Arrangement of Sections ______Chapter I Preliminary Sections 1

THE BIHAR AND WEST BENGAL (TRANSFER OF TERRITORIES) ACT, 1956 _______ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS ________ CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title. 2. Definitions. PART II TRANSFER OF TERRITORIES 3. Transfer of territories from Bihar to West Bengal. 4. Amendment of First Schedule to the Constitution. PART III REPRESENTATION IN THE LEGISLATURES Council of States 5. Amendment of Fourth Schedule to the Constitution. 6. Bye-elections to fill vacancies in the Council of States. 7. Term of office of members of the Council of States. House of the people 8. Provision as to existing House of the People. Legislative Assemblies 9. Allocation of certain sitting members of the Bihar Legislative Assembly. 10. Duration of Legislative Assemblies of Bihar and West Bengal. Legislative Councils 11. Bihar Legislative Council. 12. West Bengal Legislative Council. Delimitation of Constituencies 13. Allocation of seats in the House of the People and assignment of seats to State Legislative Assemblies. 14. Modification of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Orders. 15. Determination of population of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. 16. Delimitation of constituencies. PART IV HIGH COURTS 17. Extension of jurisdiction of, and transfer of proceedings to, Calcutta High Court. 18. Right to appear in any proceedings transferred to Calcutta High Court. 19. Interpretation. 1 PART V AUTHORISATION OF EXPENDITURE SECTIONS 20. Appropriation of moneys for expenditure in transferred Appropriation Acts. 21. Distribution of revenues. PART VI APPORTIONMENT OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES 22. Land and goods. 23. Treasury and bank balances. 24. Arrears of taxes. 25. Right to recover loans and advances. 26. Credits in certain funds. -

Dr.Shyamal Kanti Mallick Designation

Dr.Shyamal Kanti Mallick M.Sc,B.Ed., Ph.D.,FTE Designation: Associate Professor Department: Botany Ramananda College, Bishnupur Bankura, West Bengal, India E-mail:[email protected] AREAS OF INTEREST/SPECIALISATION • Ecology and Taxonomy of Angiosperms • Ethnobotany • Plant diversity ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENTS • B.Sc. (Hons.in Botany) degree from Vidyasagar University • M. Sc.( Botany) degree from Vidyasagar University • Ph,D. ( Botany) degree from Vidyasagar University RESEARCH EXPERIENCE From To Name and Address of Funding Position held Agency / Organization 1997 2002 Vidyasagar University Scholar 2008 2020 Burdwan University & Project Supervisor at Bankura University PG level 2017 Till date Bankura University Ph.D. Supervisor ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE • Teaching experience at H.S. School level from 10.12.91 to 21.03.2005 • Teaching experience at UG level from 22.03.2005 to till date • Teaching experience at PG level from 2008 to till date • PG level Supervisor from 2008 to till date • Ph. D. Level Supervisor from 28.11.17 to till date ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE • PGBS Member of Burdwan University • UGBS & PGBS Member of Bankura University • Departmental Head of Ramananda College from 01.07.2012 to30.06.2014 • Syllabus Committee ( P.G.) of Midnapore College ( Autonomous) • Member of Ph.D. committee of Bankura University. PUBLICATIONS (List of Journals/Proceedings/Chapter in Books) 1. Mukherjee,S. and Mallick, S.K.(2020 ). An Ethnobotanica study of Ajodhya Forest Range of Purulia District, West Bengal. “Asian Resonance ” 9(4): 104-107. 2. Mallick, S.K.(2020 ). An Ethnobotanical stydy on Tajpur Village of Bankura District “Asian Resonance ” 9(3): 1-6. 3. Mallick, S.K.(2017 ). -

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

Azad Hind Fauj and Provisional Government : a Saga of Netaji Prof

Orissa Review * August - 2004 Azad Hind Fauj and Provisional Government : A Saga of Netaji Prof. Jagannath Mohanty "I have said that today is the proudest day of fact one of his greatest speeches which my life. For enslaved people, there can be no overwhelmed the entire contingents of Indian greater pride, no higher honour, than to be the National Army (INA) gathered there under the first soldier in the army of liberation. But this scorching tropical sun of Singapore. There was honour carries with it a corresponding a rally of 13,000 men drawn from the people responsibility and I am deeply of South-East Asian countries. conscious of it. I assure you Then Netaji toured in Thailand, that I shall be with you in Malay, Burma, Indo-China and darkness and in sunshine, in some other countries and sorrows and in joy, in suffering inspired the civilians to join the and in victory. For the present, army and mobilised public I can offer you nothing except opinion for recruitment of hunger, thirst, privation, forced soldiers, augmenting resources marches and deaths. But if you and establishing new branches follow me in life and in death of Indian National Army. He - as I am confident you will - I promised the people that he shall lead you to victory and would open the second war of freedom. It does not matter Independence and set up a who among us will live to see provisional Government of India free. It is enough that Free India under whose banner India shall be free and that we shall give our three million Indians of South-East Asia would all to make her free. -

Registration Form Inviting You to the PHYSICON-2019: the XXXI S T Annual Discussion Will Be Under the Following Heads

OUTLINE OF THE PROGRAMME Places of Interest Near Bankura PHYSICON-2019 PHYSICON-2019 will discuss the importance of Physiology PHYSICON-2019 as a basic science to promote teaching and research. The Mukutmanipur is nearby conference will have technical sessions including key note major tourist attractions in st XXXI Annual Conference of the Physiological Society of India address by eminent scientists, symposium, seminar, oral Khatra subdivision. The XXXI Annual Conference of the Physiological Society of India th th ANNOUNCEMENT/ INVITATION and poster presentations. In addition, a number of second biggest earth dam of 15 – 17 November, 2019 Dear Colleagues, distinguished speakers will deliver orations conferred by I n d i a i s l o c a t e d i n On behalf of the Organizing Committee, it is a great pleasure in the Physiological Society of India (PSI). The topics of Mukutmanipur 55 km away Registration Form inviting you to the PHYSICON-2019: The XXXI s t Annual discussion will be under the following heads. from Bankura Conference of the Physiological Society of India (PSI) “Recent Name: Prof./Dr./Mr./Ms……………………………………………... Trends in Physiology and Healthcare Research for Salubrious Cardiovascular Physiology Designation………………………………………………………………… Society” held at the Bankura Christian College, Bankura- Respiratory Physiology Susunia Hill (1,200 ft.) is a th th Department:…………………………………………………..………….. 722101, West Bengal, India, during 15 – 17 November, 2019. Renal Physiology known archeological and Institution….……………………………………………..………………… Bankura Christian College as a premier higher education GI Physiology fossil site. It is a place of institution is now a brand name in academia. The college has archaeological interest and a City………………………........….. -

CBCS-HISTORY-PG-SYLLABUS.Pdf

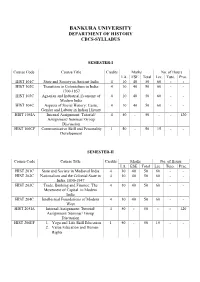

BANKURA UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CBCS-SYLLABUS SEMESTER-I Course Code Course Title Credits Marks No. of Hours I.A. ESE Total Lec. Tuto. Prac. HIST 101C State and Society in Ancient India 4 10 40 50 60 - - HIST 102C Transition to Colonialism in India: 4 10 40 50 60 - - 1700-1857 HIST 103C Agrarian and Industrial Economy of 4 10 40 50 60 - - Modern India HIST 104C Aspects of Social History: Caste, 4 10 40 50 60 - - Gender and Labour in Indian History HIST 105IA Internal Assignment: Tutorial/ 4 50 - 50 - - 120 Assignment/ Seminar/ Group Discussion HIST 106CF Communicative Skill and Personality 1 50 - 50 15 - - Development SEMESTER-II Course Code Course Title Credits Marks No. of Hours I.A. ESE Total Lec. Tuto. Prac. HIST 201C State and Society in Medieval India 4 10 40 50 60 - - HIST 202C Nationalism and the Colonial State in 4 10 40 50 60 - - India: 1858-1947 HIST 203C Trade, Banking and Finance: The 4 10 40 50 60 - - Movement of Capital in Modern India HIST 204C Intellectual Foundations of Modern 4 10 40 50 60 - - West HIST 205IA Internal Assignment: Tutorial/ 4 50 - 50 - - 120 Assignment/ Seminar/ Group Discussion HIST 206EF 1. Yoga and Life Skill Education 1 50 - 50 15 - - 2. Value Education and Human Rights SEMESTER-III Course Course Title Credits Marks No. of Hours Code I.A. ESE Total Lec. Tuto. Prac. HIST 301C Historiography and 4 10 40 50 60 - - Historical Methods HIST 302C Birth of the Modern 4 10 40 50 60 - - World: Capitalism and Colonialism in Historical Perspective HIST Colonialism and its 4 10 40 50 60 - - 303EA Impact on Indian Society and Culture HIST Crime, Law and Society 4 10 40 50 60 304EIDA in Colonial India HIST304 Studies in Literary 4 10 40 50 60 - - EIDB Culture and Identities in Modern India HIST Dissertation , viva voce 4 - - 30+20=50 - - 120+15(Library) 305IA (D,V) SEMESTER-IV Course Course Title Credits Marks No. -

State City Hospital Name Address Pin Code Phone K.M

STATE CITY HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS PIN CODE PHONE K.M. Memorial Hospital And Research Center, Bye Pass Jharkhand Bokaro NEPHROPLUS DIALYSIS CENTER - BOKARO 827013 9234342627 Road, Bokaro, National Highway23, Chas D.No.29-14-45, Sri Guru Residency, Prakasam Road, Andhra Pradesh Achanta AMARAVATI EYE HOSPITAL 520002 0866-2437111 Suryaraopet, Pushpa Hotel Centre, Vijayawada Telangana Adilabad SRI SAI MATERNITY & GENERAL HOSPITAL Near Railway Gate, Gunj Road, Bhoktapur 504002 08732-230777 Uttar Pradesh Agra AMIT JAGGI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL Sector-1, Vibhav Nagar 282001 0562-2330600 Uttar Pradesh Agra UPADHYAY HOSPITAL Shaheed Nagar Crossing 282001 0562-2230344 Uttar Pradesh Agra RAVI HOSPITAL No.1/55, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2521511 Uttar Pradesh Agra PUSHPANJALI HOSPTIAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Pushpanjali Palace, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2527566 Uttar Pradesh Agra VOHRA NURSING HOME #4, Laxman Nagar, Kheria Road 282001 0562-2303221 Ashoka Plaza, 1St & 2Nd Floor, Jawahar Nagar, Nh – 2, Uttar Pradesh Agra CENTRE FOR SIGHT (AGRA) 282002 011-26513723 Bypass Road, Near Omax Srk Mall Uttar Pradesh Agra IIMT HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Ganesh Nagar Lawyers Colony, Bye Pass Road 282005 9927818000 Uttar Pradesh Agra JEEVAN JYOTHI HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTER Sector-1, Awas Vikas, Bodla 282007 0562-2275030 Uttar Pradesh Agra DR.KAMLESH TANDON HOSPITALS & TEST TUBE BABY CENTRE 4/48, Lajpat Kunj, Agra 282002 0562-2525369 Uttar Pradesh Agra JAVITRI DEVI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 51/10-J /19, West Arjun Nagar 282001 0562-2400069 Pushpanjali Hospital, 2Nd Floor, Pushpanjali Palace, -

W.B.C.S.(Exe.) Officers of West Bengal Cadre

W.B.C.S.(EXE.) OFFICERS OF WEST BENGAL CADRE Sl Name/Idcode Batch Present Posting Posting Address Mobile/Email No. 1 ARUN KUMAR 1985 COMPULSORY WAITING NABANNA ,SARAT CHATTERJEE 9432877230 SINGH PERSONNEL AND ROAD ,SHIBPUR, (CS1985028 ) ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS & HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 14-01-1962 E-GOVERNANCE DEPTT. 2 SUVENDU GHOSH 1990 ADDITIONAL DIRECTOR B 18/204, A-B CONNECTOR, +918902267252 (CS1990027 ) B.R.A.I.P.R.D. (TRAINING) KALYANI ,NADIA, WEST suvendughoshsiprd Dob- 21-06-1960 BENGAL 741251 ,PHONE:033 2582 @gmail.com 8161 3 NAMITA ROY 1990 JT. SECY & EX. OFFICIO NABANNA ,14TH FLOOR, 325, +919433746563 MALLICK DIRECTOR SARAT CHATTERJEE (CS1990036 ) INFORMATION & CULTURAL ROAD,HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 28-09-1961 AFFAIRS DEPTT. ,PHONE:2214- 5555,2214-3101 4 MD. ABDUL GANI 1991 SPECIAL SECRETARY MAYUKH BHAVAN, 4TH FLOOR, +919836041082 (CS1991051 ) SUNDARBAN AFFAIRS DEPTT. BIDHANNAGAR, mdabdulgani61@gm Dob- 08-02-1961 KOLKATA-700091 ,PHONE: ail.com 033-2337-3544 5 PARTHA SARATHI 1991 ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER COURT BUILDING, MATHER 9434212636 BANERJEE BURDWAN DIVISION DHAR, GHATAKPARA, (CS1991054 ) CHINSURAH TALUK, HOOGHLY, Dob- 12-01-1964 ,WEST BENGAL 712101 ,PHONE: 033 2680 2170 6 ABHIJIT 1991 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SHILPA BHAWAN,28,3, PODDAR 9874047447 MUKHOPADHYAY WBSIDC COURT, TIRETTI, KOLKATA, ontaranga.abhijit@g (CS1991058 ) WEST BENGAL 700012 mail.com Dob- 24-12-1963 7 SUJAY SARKAR 1991 DIRECTOR (HR) BIDYUT UNNAYAN BHAVAN 9434961715 (CS1991059 ) WBSEDCL ,3/C BLOCK -LA SECTOR III sujay_piyal@rediff Dob- 22-12-1968 ,SALT LAKE CITY KOL-98, PH- mail.com 23591917 8 LALITA 1991 SECRETARY KHADYA BHAWAN COMPLEX 9433273656 AGARWALA WEST BENGAL INFORMATION ,11A, MIRZA GHALIB ST. agarwalalalita@gma (CS1991060 ) COMMISSION JANBAZAR, TALTALA, il.com Dob- 10-10-1967 KOLKATA-700135 9 MD. -

Chapter 5 an Overview of Medinipur District

Chapter 5 An overview of Medinipur District CHAPTER 5 AN OVERVIEW OF MEDINIPUR DISTRICT 5.1 BACKGROUND Undivided Medinipur was the biggest district in the area (22°57’10’’N to 21°36’35’’N and 88°12’40’’E to 86°33’50’’E) of West Bengal (“Brief Industrial”). Census report 2011, reveals Medinipur district as having an area of 9,368 sq. km. and the population is 59,13,457 where 3,007,885 males and 2,905,572 females (“Paschim Medinipur”). The famous Chinese traveller Fa-hien and Hiuen Tsang visited Tamralipta (modern Tamluk). Midnapore town became the headquarters of Medinipur district which became famous for the struggle of independence against the British Administration (“District Census” 9). The district was divided into Paschim Medinipur and Purba Medinipur on 1st January, 2002 (“Brief Industrial”). The district of Paschim Medinipur is situated in the extension of Chota Nagpur plateau gradually sloping towards East and South (“District Human” 5). South-eastern railway track from Howrah to Adra runs through this district and also state highway no. 60 runs parallel to the railway track. The national highway no. 6 (Bombay road) also runs through this district. The western part of this south-eastern railway track in Paschim Medinipur is infertile laterite rocks and mostly laterite soil whereas the eastern part is fertile alluvial. The district of Paschim Medinipur has 3 Subdivisions, namely i) Ghatal ii) Kharagpur iii) Midnapore Sadar (“District Census” 20), 21 Blocks, 21 Panchayat Samity, 1 Zilla Parishad, 15 Members of the Legislative Assembly and 2 Members of Parliament (“Panchayat and R. -

Census of India 1941, Bengal, Table Part II India

- ---------------_-----_ ---- -:- , ------- fq~~ ~G(R ~ ~l~ 'revio"'u~ References Later Referei:lces I-AREA, HOUSES AND POPULATION This table,borresponds to Imperial Table I of 1931 and shows for divisions, dIstricts and states the t.Tea, the num}{er of houses and inhabited rural mauzas, and the distribution of occupied houses and popula tion between Jural and urban areas. Similar-details for subdivisions ?>nd police-stations are shown in Pro- vincial TablE} L . 2. ThejGtl'e,as given differ in some cases from those given is the corresponding tab~ of· Hl31. "They are based on tl,1e figures supplied by the Government of Bengal. The province gained duriVg the decade an area of 18114' sq miles as a net result of transfers between Bengal, Bihar, Orissa and A$arn, th-e- details of which #e 'given below :- Area gained by transfer Area lost by transfer Districts of Bengal ...A.... __~-, ,--- --...A....--__----. Net gain to Frain .Area in To Area in Bengal sq miles sq miles 1 2 3 4 5 6 All Districts Bihar 18·92 Bihar, Orissa & Assam 0,713 +18·14 Midnapore Mayurbhanj (Orissa) 0·25 -0·25 Murshidabad ., Santhal Parganas (Bihar) 0·13 -0·13 Rangpur Goalpara (Assam) 0·40 -0·40 lV!alda .. ., Santhal Parganas +16·72 (Bihar) Dinajpur .. Purnea (Bihar) 2·20 +2·20 Details of the population. at each census in the areas affected by tbese inter-provincial transfers are given in the title page to Imperial Table II. 3. Detailed particulars of the areas treated as towns and of the variation in their numbers since 1931 .are given in Imperial Tftble V and Provincial Table I. -

History, Sculpture and Culture of Raghunath Jew Temple of Raghunath Bari, East Midnapore, India - a Photographic Essay

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 144 (2020) 397-413 EISSN 2392-2192 History, Sculpture and Culture of Raghunath Jew Temple of Raghunath Bari, East Midnapore, India - A Photographic Essay Prakash Samanta1, Pijus Kanti Samanta2,* 1Department of Environmental Science, Directorate of Distance Education, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore, West Bengal, India 2Department of Physics (PG & UG), Prabhat Kumar College, Contai - 721404, Purba Medinipur, West Bengal, India *E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Among the old temples which are under the Kashijora Pargana, Raghunath Jew temple (also known as Thakurbari) is very remarkable for its sculpture and culture of seventeenth century. This is a very old temple in the worship of Goddess Rama-Sita. The temple is a unique with its ancient constructions, and sculpture in its walls, and columns. A festival in the worship of lord Rama is held every year on Dashera and runs over a month. People of all community, caste and culture assemble in this festival. This festival also helps to develop the economy of not only the temple authority but also the people of the surrounding villages. The Ratha (Chariot), which runs in the day of Dashera, is very unique in the entire Midnapore district. It is made up of wood and contains several sculptural designs. Although there is as such no detailed historical record of this temple but still it is silently preserving the culture of the ancient Bengal over last three centuries. Keywords: Kashijora Pargana, Temple, Chariot, Archaeology, Bengal ( Received 24 March 2020; Accepted 15 April 2020; Date of Publication 16 April 2020 ) World Scientific News 144 (2020) 397-413 1.