Administration Lawyers and Administration Interrogation Rules (Part V)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15-L-1645/0 0 0 /194

(b )( 1) (b)(3) NatSecAct TS::SC'l' Verbatim Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribunal Hearing for IS'.'1 10024 OPENING REPORTER : On the record RECORDER: All rise. PRESIDENT: Remain seated and come to order. Go nhead. Recorder. RECORDER: This Tribunal is being conducle<l at 1328 March 10, 200 ; on board C.S. Naval Base Guantanamo Bav. Cuba. The following personnel are present: Captain (b)(6) United Slates Navy, President Lieutenant Colonel b) 6) • t..:nited States Air Force. Member Lieutenant Colonel (b)(6) United States Marine Corps. Member Lieutenant Colonel (b)(6) , United States Air F11rce, Personal Re pre sen ta the Language Analysis.+.--,...,..,,.,.---. (b)(6) ......... ..,.... Gunnery Sergeant (b)(6) l nited States Marine Corps. Reporter Lieutenant Colonel'-P!!~~) --"" . United States Anny, Recorder Captain (b)(6) 1:; c ge Advocate member »fthe Tribunal. OATH SESSION 1 RECORDER: All Rise. PRESIDE!\T: The Recorder will be sworn. Do you, Lieutenant Colonel j(b)(6) I solemnly swear that you will faithfully pcrfonn the duties as Recorder assigned in this Tribunai so help you God'' RECORDER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Reponer will now be :;worn. The Recorder will administer the oath. RECORDER: ()o you Gunnery Sergeant l(b)(6) ~wear or affinn that y<•u will faithfully <lis~: harge )'Our duties as Reporter assigned in this Tribunal ro help you God? REPORTER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Translator will be sworn. JSN #10024 Enclosure (3) Page I of27 (b )( 1) (b)(3) NatSecAct 15-L-1645/0 0 0/194 (b }( 1) (b)(3) NatSecAct TS:lSCJt RECORDER: Do you swear or affinn that you will faithrully perform 1he duties ofTranslaror in the case now in hearing so help you God? TRANSLATOR: I do PRESIDEN I': We will take a brief recess now in order in lo bring Detainee into the room. -

February 23, 2017 VIA ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION the Honorable

February 23, 2017 VIA ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION The Honorable Jeff Sessions Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530 Dear Attorney General Sessions: In the midst of ongoing, fast-paced litigation challenging Executive Order 13769, titled “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States,” Acting Attorney General Sally Yates ordered the Department of Justice not to defend the Order. In a number of those cases, Justice Department attorneys had only a few days to draft briefs or prepare for hearings at the time of Ms. Yates’ order to stop working on them. Given the very short timeframe the Department attorneys had, Ms. Yates’ instruction to them not to defend the Executive Order meaningfully reduced their preparation time, even though she was fired late on the night of January 30. As a result, the Department attorneys were not as prepared to defend the Executive Order in court as they would have been without Ms. Yates’ interference. For example, just a few days later at the hearing on the state of Washington’s motion for a temporary restraining order, the Department attorneys did not have relevant factual information on hand to answer the judge’s question about the number of terrorism-related arrests of nationals from the countries at issue in the Executive Order. As a result, they were unable to enter facts into the record to dispute the judge’s false claim that there had been none. This likely affected his decision to grant the motion for a temporary restraining order. In the appeal on that issue, the importance of that omission became clear, and was part of the basis of the appeals court’s ruling against the President. -

Video-Recorded Decapitations - a Seemingly Perfect Terrorist Tactic That Did Not Spread Martin Harrow DIIS Working Paper 2011:08 WORKING PAPER

DIIS working paper DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:08 Video-recorded Decapitations - A seemingly perfect terrorist tactic that did not spread Martin Harrow DIIS Working Paper 2011:08 WORKING PAPER 1 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:08 MARTIN HARROW MSC, PhD, Consulting Analyst at DIIS [email protected] DIIS Working Papers make available DIIS researchers’ and DIIS project partners’ work in progress towards proper publishing. They may include important documentation which is not necessarily published elsewhere. DIIS Working Papers are published under the responsibility of the author alone. DIIS Working Papers should not be quoted without the express permission of the author. DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:08 © Copenhagen 2011 Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover Design: Carsten Schiøler Layout: Ellen-Marie Bentsen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN: 978-87-7605-449-6 Price: DKK 25.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk 2 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:08 CONTENTS Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Decapitation as a weapon 5 Video-recorded decapitations 2002-2009 8 The reproductive dynamics of terrorist tactics 11 The accessibility of video-recorded decapitations as a tactic 12 Effectiveness of terrorism – impacting two different audiences 14 Why not video-recorded decapitations? 18 Iraq 18 Afghanistan 19 The West 20 Conclusion 21 List of References 23 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:08 ABSTracT Video-recorded decapitations have an enormous impact, they are cheap and easy, and they allow the terrorists to exploit the potential of the Internet. -

This Is Almost Certainly James Comey's Twitter Account

Log in / GIZMODO DEADSPIN FUSION JALOPNIK JEZEBEL KOTAKU LIFEHACKER THE Sign ROOT up This Is Almost CertainlyVIDEO SPLOID JamesPALEOFUTURE Comey’sIO9 SCIENCE REVIEWS FIELD GUIDE Twitter Account Ashley Feinberg 3/30/17 3:29pm · Filed to: JAMES COMEY 2.8M 675 226 Digital security and its discontents—from Hillary Clinton’s emails to ransomware to Tor hacks—is in many ways one of the chief concerns of the contemporary FBI. So it makes sense that the bureau’s director, James Comey, would dip his toe into the digital torrent with a Twitter account. It also makes sense, given Comey’s high profile, that he would want that Twitter account to be a secret from the world, lest his follows and favs be scrubbed for clues about what the feds are up to. What is somewhat surprising, however, is that it only took me about four hours of sleuthing to find Comey’s account, which is not protected. Last night, at the Intelligence and National Security Alliance leadership dinner, Comey let slip that he has both a secret Twitter and an Instagram account in the course of relating a quick anecdote about one of his daughters. Kevin Rincon Follow @KevRincon Fun fact: #FBI director James #Comey is on twitter & apparently on Instagram with nine followers. 8:11 PM - 29 Mar 2017 150 139 Who am I to say no to a challenge? As far as finding Comey’s Twitter goes, the only hint he offered was the fact that he has “to be on Twitter now,” meaning that the account would likely be relatively new. -

Pakistan's Terrorism Dilemma

14 HUSAIN HAQQANI Pakistan’s Terrorism Dilemma For more than a decade, Pakistan has been accused of sup- porting terrorism, primarily due to its support for militants opposing Indian rule in the disputed Himalayan territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Until September 11, 2001, Islamabad was also the principal backer of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Although Pakistan has now become a key U.S. ally in the war against terrorism, it is still seen both as a target and staging ground for terrorism. General Pervez Musharraf ’s military regime abandoned its alliance with the Taliban immediately after the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington. U.S. forces were allowed the use of Pakistani air bases for operations in Afghanistan. Pakistani intelligence services provided, and continue to provide, valuable information in hunting down Taliban and al-Qaeda escapees. The Pakistani military is cur- rently working with U.S. law enforcement officials in tracking down terrorists in the lawless tribal areas bordering Afghanistan. In a major policy speech on January 12, 2002, Musharraf announced measures to limit the influence of Islamic militants at home, including those previously described by him as “Kashmiri free- dom fighters.” “No organizations will be able to carry out terrorism 351 352 HUSAIN HAQQANI on the pretext of Kashmir,” he declared. “Whoever is involved with such acts in the future will be dealt with strongly whether they come from inside or outside the country.”1 Musharraf ’s supporters declared his speech as revolutionary.2 He echoed the sentiment of most Pakistanis when he said, “violence and terrorism have been going on for years and we are weary and sick of this Kalashnikov culture … The day of reckoning has come.” After the speech, the Musharraf regime clamped down on domes- tic terrorist groups responsible for sectarian killings.3 But there is still considerable ambivalence in Pakistan’s attitude toward the Kashmiri militants. -

Torture and the Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment of Detainees: the Effectiveness and Consequences of 'Enhanced

TORTURE AND THE CRUEL, INHUMAN AND DE- GRADING TREATMENT OF DETAINEES: THE EFFECTIVENESS AND CONSEQUENCES OF ‘EN- HANCED’ INTERROGATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 8, 2007 Serial No. 110–94 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–765 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:46 Jul 29, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\CONST\110807\38765.000 HJUD1 PsN: 38765 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MAXINE WATERS, California DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah ROBERT WEXLER, Florida RIC KELLER, Florida LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California DARRELL ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee MIKE PENCE, Indiana HANK JOHNSON, Georgia J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia BETTY SUTTON, Ohio STEVE KING, Iowa LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM FEENEY, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas ANTHONY D. -

Fight Terror, Not Twitter: Insulating Social Media from Material Support Claims

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 37 Number 1 Article 1 Fall 2016 Fight Terror, Not Twitter: Insulating Social Media From Material Support Claims Nina I. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Nina I. Brown, Fight Terror, Not Twitter: Insulating Social Media From Material Support Claims, 37 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 1 (2017). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol37/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ELR – BROWN (V4) (DO NOT DELETE) 1/17/2017 5:09 PM FIGHT TERROR, NOT TWITTER: INSULATING SOCIAL MEDIA FROM MATERIAL SUPPORT CLAIMS NINA I. BROWN Social media companies face a new threat: as millions of users around the globe use their platforms to exchange ideas and information, so do terrorists. Terrorist groups, such as ISIS, have capitalized on the ability to spread propaganda, recruit new members, and raise funds through social media at little to no cost. Does it follow that when these terrorists attack, social media is on the hook for civil liability to victims? Recent lawsuits by families of victims killed in terrorist attacks abroad have argued that the proliferation of terrorists on social media—and social media’s reluctance to stop it—violates the Antiterrorism Act. -

Leaderless Jihad West Point Ctc Summaries

ALL FEl INFflRNITIuII CONTAINED NEPEIN Tl1JCLPSIFIED DATE O1 LI 5l DIm1shn WEST POINT CTC SUMMARIES IC LEADERLESS JIHAD Terror Networks in the Twenty-First Century flivcrsit\ Pclms\ 1\ jnia Press 2015 The Islamist terrorist threat is radicalization Dr Marc Sageman MD global rapidly evolving process Islamic terror networks of the twenty-first century are before it reaches its Ph.D is forensic psychia more fluid and violent end The most effective trist and government coun becoming independent unpredictable than their more structured forebears that conducted countermeasure to tcrtcrrorism consultant He This book builds combat the homegrown holds various academic and die 9/11 attacks The present direat in the West has upon Dr Sagemans terrorist threat is evolved from infiltration outside trained includ by terronsts to the professional positions previous volume interrupt Scholar in Residence against ivhom international cooperation and border radicalization process ing at Understanding Ter before effective it reaches its the York Police protection are to homegrown self-financed New Depart ror 1\Tetlrorks 2004 vioient end Senior Fellow the self-trained terrorists Dr Sageman describes this ment at and utilizes die same scattered network of wannabes Research In global homegrown Porcign Policy approach of apply- as leaderless ihad The that form this stitute and Clinical Assistant groups ing the scientific method to the study of terronsm movement are physically uncoimected from al Qaeda Professor at the University Whereas in his book the author worked -

Global War on Terrorism and Prosecution of Terror Suspects: Select Cases and Implications for International Law, Politics, and Security

GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM AND PROSECUTION OF TERROR SUSPECTS: SELECT CASES AND IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL LAW, POLITICS, AND SECURITY Srini Sitaraman Introduction The global war on terrorism has opened up new frontiers of transnational legal challenge for international criminal law and counterterrorism strategies. How do we convict terrorists who transcend multiple national boundaries for committing and plotting mass atrocities; what are the hurdles in extraditing terrorism suspects; what are the consequences of holding detainees in black sites or secret prisons; what interrogation techniques are legal and appropriate when questioning terror suspects? This article seeks to examine some of these questions by focusing on the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), particularly in the context of counterterrorism strategies that the United States have pursued towards Afghanistan-Pakistan (Af-Pak) since the September 2001 terror attacks on New York and Washington D.C. The focus of this article is on the methods employed to confront terror suspects and terror facilitators and not on the politics of cooperation between the United States and Pakistan on the Global War on Terrorism or on the larger military operation being conducted in Afghanistan and in the border regions of Pakistan. This article is not positioned to offer definitive answers or comprehensive analyses of all pertinent issues associated with counterterrorism strategies and its effectiveness, which would be beyond the scope of this effort. The objective is to raise questions about the policies that the United States have adopted in conducting the war on terrorism and study its implications for international law and security. It is to examine whether the overzealousness in the execution of this war on terror has generated some unintended consequences for international law and complicated the global judicial architecture in ways that are not conducive to the democratic propagation of human rights. -

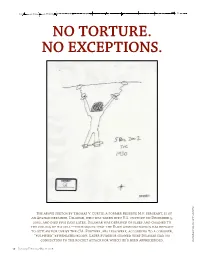

No Torture. No Exceptions

NO TORTURE. NO EXCEPTIONS. The above sketch by Thomas V. Curtis, a former Reserve M.P. sergeant, is of New York Times an Afghan detainee, Dilawar, who was taken into U.S. custody on December 5, 2002, and died five days later. Dilawar was deprived of sleep and chained to the ceiling of his cell—techniques that the Bush administration has refused to outlaw for use by the CIA. Further, his legs were, according to a coroner, “pulpified” by repeated blows. Later evidence showed that Dilawar had no connection to the rocket attack for which he’d been apprehended. A sketch by Thomas Curtis, V. a Reserve M.P./The 16 January/February/March 2008 Introduction n most issues of the Washington Monthly, we favor ar- long-term psychological effects also haunt patients—panic ticles that we hope will launch a debate. In this issue attacks, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic-stress Iwe seek to end one. The unifying message of the ar- disorder. It has long been prosecuted as a crime of war. In our ticles that follow is, simply, Stop. In the wake of Septem- view, it still should be. ber 11, the United States became a nation that practiced Ideally, the election in November would put an end to torture. Astonishingly—despite the repudiation of tor- this debate, but we fear it won’t. John McCain, who for so ture by experts and the revelations of Guantanamo and long was one of the leading Republican opponents of the Abu Ghraib—we remain one. As we go to press, President White House’s policy on torture, voted in February against George W. -

July 13, 2020 the Honorable William P. Barr Attorney General U.S

July 13, 2020 The Honorable William P. Barr Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20530 Dear Attorney General Barr: President Trump’s commutation of Roger Stone’s prison sentence for obstructing a bipartisan congressional investigation raises serious questions about whether this extraordinary intervention was provided in exchange for Mr. Stone’s silence about incriminating acts by the President. During your confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2019, I asked whether you “believe a President could lawfully issue a pardon in exchange for the recipient’s promise not to incriminate him.”1 Without hesitation or caveat – and under oath – you responded: “No, that would be a crime.”2 Given recently surfaced information indicating that President Trump may have commuted Mr. Stone’s sentence in exchange for his refusal to incriminate the President, pursuant to your own standard, an inquiry by the Justice Department into Mr. Stone’s commutation is clearly warranted. Thanks to recent Freedom of Information Act lawsuits, newly unredacted portions of Special Counsel Mueller’s report reveal that multiple witnesses confirmed then-candidate Trump’s direct knowledge and encouragement of Roger Stone’s efforts to release damaging information about Hillary Clinton stolen by Russian hackers.3 These witnesses’ observations flatly contradict President Trump’s repeated denials of having such knowledge of Mr. Stone’s activities in his written responses to Special Counsel Mueller’s questions.4 After submitting these suspect answers to the Special Counsel, President Trump took to twitter and praised Mr. Stone for being “brave” and having “guts” for refusing to cooperate with investigators and provide incriminating testimony against him.5 Special Counsel Mueller observed that the President’s tweets about 1 Meg Wagner, Veronica Rocha, & Amanda Wills, Trump’s Attorney General Pick Faces Senate Hearing, CNN (last updated Jan. -

Danielle Keats Citron, Professor of Law, Boston University School of Law

PREPARED WRITTEN TESTIMONY AND STATEMENT FOR THE RECORD FOR Danielle Keats Citron, Professor of Law, Boston University School of Law HEARING ON “Fostering a Healthier Internet to Protect Consumers” BEFORE THE House Committee on Energy and Commerce October 16, 2019 John D. Dingell Room, 2123, Rayburn House Office Building Washington, D.C. INTRODUCTION Thank you for inviting me to appear before you to testify about corporate responsibility for online activity and fostering a healthy internet to protect consumers. My name is Danielle Keats Citron. I am a Professor of Law at the Boston University School of Law. In addition to my home institution, I am an Affiliate Faculty at the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard Law School, Affiliate Scholar at Stanford Law School’s Center on Internet & Society, Affiliate Fellow at Yale Law School’s Information Society Project, and Tech Fellow at NYU Law’s Policing Project. I am also a 2019 MacArthur Fellow. My scholarship focuses on privacy, free speech, and civil rights. I have published more than 30 articles in major law reviews and more than 25 opinion pieces for major news outlets.1 My book Hate Crimes in Cyberspace tackled the phenomenon of cyber stalking and what law, companies, and society can do about it.2 As a member of the American Law Institute, I serve as an adviser on Restatement (Third) Torts: Defamation and Privacy and the Restatement (Third) Information Privacy Principles Project. In my own writing and with coauthors Benjamin Wittes, Robert Chesney, Quinta Jurecic, and Mary Anne Franks, I have explored the significance of Section 230 to civil rights and civil liberties in a digital age.3 * * * Summary: In the early days of the commercial internet, lawmakers recognized that federal agencies could not possibly tackle all noxious activity online.