How to Succeed in Your Digital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equipment Leasing in Africa Handbook of Regional Statistics 2017 Including an Overview of 10 Years of IFC Leasing Intervention in the Region

AFRICA LEASING FACILITY II Equipment Leasing in Africa Handbook of Regional Statistics 2017 Including an overview of 10 years of IFC leasing intervention in the region © 2017 INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Washington, DC 20433 All rights reserved. First printing, March 2018. This document may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of the International Finance Corporation. This information, while based on sources that IFC considers to be reliable, is not guaranteed as to accuracy and does not purport to be complete. The conclusions and judgments contained in this handbook should not be attributed to, and do not necessarily represent the views of IFC, its partners, or the World Bank Group. IFC and the World Bank do not guarantee the accuracy of the data in this publication and accept no responsibility for any consequence of its use. Rights and Permissions Reference Section III. What is Leasing? and parts of Section IV. Value of Leasing in Emerging Economies are taken from IFC’s “Leasing in Development: Guidelines for Emerging Economies.” 2005, which draws upon: Halladay, Shawn D., and Sudhir P. Amembal. 1998. The Handbook of Equipment Leasing, Vol. I-II, P.R.E.P. Institute of America, Inc., New York, N.Y.: Available from Amembal, Deane & Associates. EQUIPMENT LEASING IN AFRICA: ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Acknowledgement This first edition of Equipment Leasing in Africa: A handbook of regional statistics, including an overview of 10 years of IFC leasing intervention in the region, is a collaborative efort between IFC’s Africa Leasing Facility team and the regional association of leasing practitioners, known as Africalease. -

Determinants of Procurement Performance in Commercial Banks Within East Africa?

DETERMINANTS OF PROCUREMENT PERFORMANCE IN COMMERCIAL BANKS WITHIN EAST AFRICA BY EVANS JUMA LUKETERO A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI OCTOBER, 2016 DECLARATION This Research Project is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University …………………………………….. ………………………… Signature Date EVANS JUMA LUKETERO Reg. No: D61/69206/2011 This Research Project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University Supervisor MR. MICHAEL K. CHIRCHIR …………………………………….. ………………………… Signature Date ii DEDICATION I dedicate this research proposal to all the Banks in East Africa, to family especially my wife Rineldah Asiko, My daughter Adalia Juma and friends for their support and prayers during my studies. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank the Almighty Lord for the gifts of Grace and Perseverance accorded to me. I would also like to acknowledge all my course lecturers and colleagues for their sincere support. Most important, I sincerely wish to acknowledge the support from my supervisor without whom I could not have gone this far with my project work. I owe you my gratitude. iv ABSTRACT Procurement efficiency is the association that exists between planned and actual required resources needed to realize formulated goals and objectives as well as their related activities. The improvement of procurement performance would ensure that sourced firm materials are indeed procured during the right time at suitable cost. This would in turn enable improvements in organization procurement process leading to improvements on quality of offered products and services at minimum cost. -

Digital Access: the Future of Financial Inclusion in Africa Acronyms

DIGITAL ACCESS: THE FUTURE OF FINANCIAL INCLUSION IN AFRICA ACRONYMS ADC Alternative Delivery Channel ISO International Organization for Standardization AFSD African Financial Sector Database IT Information Technology ARPU Average Revenue Per User KES Kenyan Shilling API Application Programming Interface KPI Key Performance Indicator ATM Automated Teller Machine KYC Know Your Customer B2P Business to Person LAPO MfB Lift Above Poverty Organization BCEAO Central Bank of West Africa (Banque Centrale Microfinance Bank des Etats de l’Afrique de l’Ouest) M-banking Mobile Banking BOI Banking Operations Intermediary M-wallet Mobile Wallet BVN Bank Verification Number MFI Microfinance Institution CEO Chief Executive Officer MM Mobile Money CBA Commercial Bank of Africa MSME Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise CBN Central Bank of Nigeria MTN Mobile Telephone Network CFA West African Franc, or Central African Franc MNO Mobile Network Operator CGAP Consultative Group to Assist the Poor MVNO Mobile Virtual Network Operator CRM Customer Relationship Management NFC Near Field Communication DFS Digital Financial Services OTC Over the Counter DJ Disc Jockey P2B Person to Business DVD Digital Versatile Disc P2P Person to Person E-banking Electronic Banking PC Personal Computer EFT Electronic Funds Transfer PIN Personal Identification Number EMI e-Money Issuer POS Point of Sale E-money Electronic Money PSP Payment Service Provider E-wallet Electronic Wallet E-warehousing Electronic Warehousing QR Quick Response FCMB First City Monument Bank RCT Randomized -

Competitive Strategies and Performance of Equity Bank in Kenya

COMPETITIVE STRATEGIES AND PERFORMANCE OF EQUITY BANK IN KENYA NYAGA ANDREW IRERI A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION SCHOOL OF BUSINESS UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI MAY, 2016 DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been presented for examination in any other university. Signature...................................... Date......................................... NYAGA ANDREW IRERI (D61/72455/2014) This research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University Supervisor. Signature...................................... Date......................................... DR. JOHN YABS SENIOR LECTURER DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION SCHOOL OF BUSINESS UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I thank the almighty God for seeing me through my entire Master‟s Degree course. Indeed God‟s providence and unfailing mercy have made this possible. I wish to acknowledge the University of Nairobi for the support accorded to me during the entire course. I am indeed grateful to my supervisor, my moderator and lecturers for the support, encouragement, guidance and constructive criticism which I was able to complete my project. I thank all the respondents who spend their precious time and participated in the research and answered my questions in the interview guide. iii DEDICATION This project is dedicated to parents who inspired me to acquire my academic potential and supporting me throughout my MBA. I highly cherish your love, encouragement, support, and guidance throughout all these years. May the Almighty God bless you. iv ABSTRACT Modern banking sector operates in a dynamic and turbulent environment faced with variety of challenges brought about by competition in the sector. -

Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options

Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options Research report Editors: Madhyam & SOMO December 2010 Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options Research report By: Lawrence Bategeka & Luka Jovita Okumu (Economic Policy Research Centre, Uganda) Editors: Kavaljit Singh (Madhyam), Myriam Vander Stichele (SOMO) December 2010 SOMO is an independent research organisation. In 1973, SOMO was founded to provide civil society organizations with knowledge on the structure and organisation of multinationals by conducting independent research. SOMO has built up considerable expertise in among others the following areas: corporate accountability, financial and trade regulation and the position of developing countries regarding the financial industry and trade agreements. Furthermore, SOMO has built up knowledge of many different business fields by conducting sector studies. 2 Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options Colophon Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda: Process, Results and Policy Options Research report December 2010 Authors: Lawrence Bategeka and Luka Jovita Okumu (EPRC) Editors: Kavaljit Singh (Madhyam) and Myriam Vander Stichele (SOMO) Layout design: Annelies Vlasblom ISBN: 978-90-71284-76-2 Financed by: This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of SOMO and the authors, and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Published by: Stichting Onderzoek Multinationale Ondernemingen Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations Sarphatistraat 30 1018 GL Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: + 31 (20) 6391291 Fax: + 31 (20) 6391321 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.somo.nl Madhyam 142 Maitri Apartments, Plot No. -

Positioning Strategies on Mobile Money Transfer at Safaricom Limited

POSITIONING STRATEGIES ON MOBILE MONEY TRANSFER AT SAFARICOM LIMITED BY ROSEMARY ATIENO ADONGO SUPERVISOR DR. FLORENCE MUINDI A RESEARCH PROJECT PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTTRATION, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI NOVEMBER, 2017 DECLARATION This research proposal is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university. Signature............................................................... Date................................ Rosemary Atieno Adongo Reg No: D61/75015/2014 This research proposal has been submitted for examinations with my approval as the university supervisor. Signature...................................................... Date.............................. Dr. Florence Muindi School of Business, University of Nairobi. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I thank to the Almighty God, who has made the completion of this project possible through good health, peace of mind, supportive supervisor, friends and family who have been of great help towards the completion of this project. Most sincerely I thank Supervisor Dr. Florence Mundi for her patience, availability, professional advice; guidance and encouragement that helped me meet the deadline and success of this project. Finally I appreciate the efforts of my husband James Adunya, my children Sharon, Felix, Calistor and Allan who relentlessly encouraged me to move on regardless of the hurdles that came on my way. iii DEDICATION This project is dedicated to my family for their support their guidance and contribution in getting to where I am today and for their patience and support as I spent time and resources towards attaining my master‟s degree. iv ABSTRACT Organizations that operate in an industry with more than one firm face substantial competition if not fierce competition. -

BK Group Plc Investor Presentation

BK Group Plc Investor Presentation Page 1 Agenda 1. Key Investment Highlights 2. Country Overview Information 3. Banking Sector Overview 4. Bank Overview 5. Corporate Governance 6. Business Overview 7. Review of Financial Performance 8. Strategic Outlook 9. Contact Information Page2 2 Key Investment Highlights 1. Best Bank in Rwanda 2013, Politically stable country with sound governance 2015 & 2016 Very attractive demographic profile: population of 12 Million Sound Macro Robust economic growth averaging 8% pa in the last 5 years, expecting a sustainable high GDP growth into 2020 Fundamentals th 2. Best East African Bank 2012 Moderate inflation with rate of 0.8% as at 30 June 2019 & 2015,2016 The 2018 World Bank Doing Business Report ranked Rwanda as the 29th out of 190 economies in terms of ease of doing business and 2nd in Africa Well regulated banking sector: fairly conservative regulator relative to other regulators in the EAC Significant 3. Bank of the Year 2009- Significant headroom for growth given under-banked and excluded population 2012,2014,2015,2016 Banking Sector Potential Number of financially excluded population reduced from 28% in 2012 to only 11% in 2016 Total assets/GDP of 47.6% as at 31st, March 2019. Strong Market positioning & sustainable leadership 4. Best Bank in Rwanda 2009- Total assets FRw 893.2 billion, 27.5% market share as at June 30th, 2019; 2014,2016 Market th Leadership Net Loans FRw 650.2 billion, 29.2% market share as at June 30 , 2019; Customer Deposits FRw 551.7 billion, 26.8% market share as at June 30th, 2019; Shareholders’ Equity FRw 204.0 billion, 36.2% market share as at June 30th, 2019. -

World Bank Document

THE GAMBIA: Policies to Foster Growth Public Disclosure Authorized Volume II. Macroeconomy, Finance, Trade and Energy May 19, 2015 Trade and Competitiveness Practice Cape Verde, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania and Senegal Country Department Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank REPUBLIC OF GAMBIA –FISCAL YEAR January 1 st - December 31 st MONETARY EQUIVALENT (Exchange rate as of May 15, 2015) Currency Unit = Gambian Dalasi (GMD) 1,00 US$ = 42.6000 GMD WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS Metric System ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ABTA Association of British Travel Agents IPC Investment Promotion Center TEU Twenty-foot equivalent Unit ADR Average Daily Rate JIC Joint Industrial Council Agreement TFP Total Factor Productivity Agribusiness Services and Producers’ Trade Intensity Index ASPA LDCs Least Developed countries TII Association Association of Small Enterprises in Tourism Master Plan ASSET LFO Liquid Pilot Fuel TMP Tourism C.Pct Column Percentage LIC Low Income Countries ULC Unit Labor Cost CAR Capital Adequacy ratio LMIC Low Middle Income Countries UNDP United Nations Development Program CBG Central Bank of The Gambia MFI Microfinance institution UREP Upland Rice Expansion Program Ministry of Finance and Economic United Nations World Tourism CET Common external tariff MOFEA UNWTO Affairs Organization DB 2015 Doing business 2015 Report MTC Ministry of Tourism and Culture VFR Visiting Friends and Relatives Economic Community of West Ministry of Trade, Industry -

16045 KPMG Africa P4 Web.Indd

Africa Banking Industry Retail Customer Satisfaction Survey September 2016 kpmg.com About this survey To succeed in today’s banking environment, bank executives need to understand their customers: their preferences, their channel usage, their needs and their satisfaction. That is why we talked with more than 33,000 Understanding the methodology retail banking customers spread across 18 different African markets. We asked them what was important to them in a banking relationship. We asked them For this report (and our previous report in 2013), we what channels they currently use and what channels used our Customer Service Index (CSI) methodology they would like to use. And we asked them how to determine customer satisfaction. The CSI is a their current banks compared to their expectations. weighted score that reflects the relationship between the importance rating allocated by customers to certain measures and their satisfaction with the same Through the eyes of the customer measures. The data we collected from our conversations The CSI ranks importance and satisfaction across reflect the opinions of real banking customers. six key measures: As such, they reflect only the perceptions of customers and – as a result – they may not always be fair. Perceptions are, by defi nition, subjective. Branding To be clear: the data reported in this survey does not refl ect the opinions of KPMG member fi rms. Rather, it illustrates the feelings and experiences Value for Customer of customers based on the service they received money care at their particular banks. Delivering a balanced view Products Convenience and services For this survey, we talked with retail banking customers across 18 sub-Saharan countries Executional in Africa. -

Liberia's 9 Commercial Banks

Public Disclosure Authorized IFC Mobile Money Scoping Country Report: Liberia Public Disclosure Authorized June, 2012 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized About The MasterCard Foundation Program IFC and the MasterCard Foundation (MCF) entered into a partnership focused on accelerating the growth and outreach of microfinance and mobile financial services in Sub-Saharan Africa. The partnership aims to leverage IFC’s expanding microfinance client network in the region and its emerging expertise in mobile financial services to catalyze innovative and low-cost approaches for expanding financial services to low- income populations. The Partnership has three Primary Components Mobile Financial Service IFC and The MasterCard Foundation see tremendous opportunity with Microfinance mobile banking, particularly for those living in rural areas. Mobile phones Through this partnership, IFC will result in lower transactions costs and implement a scaling program for reduce the cost of information. This Knowledge & Learning microfinance in Africa. The primary partnership will (i) identify nascent This partnership will include a major purpose of the Program is to markets to accelerate the uptake of knowledge sharing component to accelerate delivery of financial branchless banking services, (ii) work ensure broader dissemination of services in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with private sector players to build results, impacts and lessons learned through the significant scaling up of expertise and infrastructure to from both the microfinance and between eight and ten of IFC‘s sustainably offer financial services to mobile financial services. These strongest microfinance partners in the unbanked using mobile knowledge products will include Africa. Interventions will include technology and agent networks and product and channel diversification (iii) build robust business models that into underserved areas. -

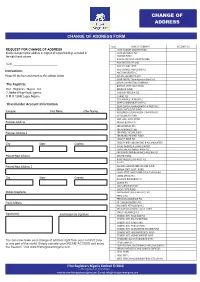

Backup of Change of Address

CHANGE OF ADDRESS CHANGE OF ADDRESS FORM TICK NAME OF COMPANY ACCOUNT NO. REQUEST FOR CHANGE OF ADDRESS ACAP CANARY GROWTH FUND Kindly change my/our address in respect of my/ourholdings as ticked in AFRICAN PAINTS PLC the right hand column ANCHOR FUND ARM AGGRESSIVE GROWTH FUND Date: _____________________________ ARM DISCOVERY FUND ARM ETHICAL FUND ASO-SAVINGS AND LOANS PLC Instructions ABC TRANSPORT PLC Please fill the form and return to the address below AUSTIN LAZ AND CO. PLC BANK PHB PLC (Now Keystone Bank Ltd) The Registrar, BCN PLC-MARKETING COMPANY BAYELSA STATE GOVT BOND First Registrars Nigeria Ltd. BEDROCK FUND 2, Abebe Village Road, Iganmu CADBURY NIGERIA PLC P. M. B. 12692 Lagos. Nigeria. CHAMS PLC COSTAIN WEST AFRICA PLC Shareholder Account Information DAAR COMMUNICATIONS PLC DEAP CAPITAL MANAGEMENT & TRUST PLC DELTA STATE GOVT BOND Surname First Name Other Names REDEEMED GLOBAL MEDIA COMPANY LTD DV BALANCED FUND EDO STATE GOVT. BOND Previous Address FAMAD NIGERIA PLC FBN HOLDINGS PLC FBN HERITAGE FUND Previous Address 2 FBN FIXED INCOME FUND FBN MONEY MARKET FUND FIDELITY BANK PLC City State Country FIDELITY NIGFUND (INCOME & ACCUMULATED) FOKAS SAVINGS & LOANS LIMITED FORTIS MICROFINANCE BANK PLC FRIESLANDCAMPINA WAMCO NIGERIA PLC Present\New Address GTBANK BOND HONEYWELL FLOUR MILLS PLC JULI PLC Present\New Address 2 KAKAWA GUARANTEED INCOME FUND KWARA STATE GOVT. BOND LAGOS STATE GOVT. BOND (1st & 2nd tranche) LEARN AFRICA PLC City State Country NIGERIAN BREWERIES PLC OANDO PLC OASIS INSURANCE PLC ONDO STATE BOND Mobile -

Sierra Leone - Mobile Money Transfer Market Study

Sierra Leone - Mobile Money Transfer Market Study FINAL REPORT, March 2013 March 2013 Report prepared by PHB Development, with the support of Disclaimer The contents of this report are the responsibility of PHB Development and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cordaid. The information contained in this report and any errors or mistakes that occurred are the sole responsibility of PHB Development. 2 Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………3 Executive Summary and Recommendations………………………………............... 9 I. Module 1 Regulation and Partnerships (Supply side)……………………………….23 II. Module 2 Markets and products (Demand side )……………………………………..56 III. Module 3 Distribution Networks………………………………………………………..74 IV. Module 4 MFI Internal Capacity………………………………………………………..95 V. Module 5 Scenario's for Mobile Money Transfers and the MFIs in Sierra Leone...99 3 Introduction Cordaid has invited PHB Development to execute a market study on Mobile Money Transfers (MMT) in Sierra Leone and on the opportunities this market offers for Microfinance Institutions (MFIs). This study follows on the MITAF1 programme that Cordaid co-financed in the period 2004-2011. The results of the market study were shared in an interactive workshop in Sierra Leone on 26 February 2013. 27 persons attended, representing MFIs, MMT providers, the Bank of Sierra Leone and the donor. This final report represents an overview of the information collected, on which the workshop has been based. Moreover, information obtained during the workshop is reflected in this document. In addition, the MFIs have received individual assessment reports on their readiness for MMT. This report starts with an executive summary followed by recommendations for the MFIs and Cordaid. Chapters 1-5 provide detailed information on the regulation and the supply side of market players and MMT partnerships (module 1), on the demand for financial products (module 2) and the agent networks in Sierra Leone (module 3).