Diagnosis and Control of Foot-And-Mouth Disease in Sri Lanka Using Elisa-Based Technologies — Assessment of Immune Response to Vaccination Against Fmd Using Elisa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dress Fashions of Royalty Kotte Kingdom of Sri Lanka

DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KINGDOM OF SRI LANKA . DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KINGDOM OF SRI LANKA Dr. Priyanka Virajini Medagedara Karunaratne S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd. Dedication First Edition : 2017 For Vidyajothi Emeritus Professor Nimal De Silva DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KingDOM OF SRI LANKA Eminent scholar and ideal Guru © Dr. Priyanka Virajini Medagedara Karunaratne ISBN 978-955-30- Cover Design by: S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd Page setting by: Nisha Weerasuriya Published by: S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd. 661/665/675, P. de S. Kularatne Mawatha, Colombo 10, Sri Lanka. Printed by: Chathura Printers 69, Kumaradasa Place, Wellampitiya, Sri Lanka. Foreword This collection of writings provides an intensive reading of dress fashions of royalty which intensified Portuguese political power over the Kingdom of Kotte. The royalties were at the top in the social strata eventually known to be the fashion creators of society. Their engagement in creating and practicing dress fashion prevailed from time immemorial. The author builds a sound dialogue within six chapters’ covering most areas of dress fashion by incorporating valid recorded historical data, variety of recorded visual formats cross checking each other, clarifying how the period signifies a turning point in the fashion history of Sri Lanka culminating with emerging novel dress features. This scholarly work is very much vital for university academia and fellow researches in the stream of Humanities and Social Sciences interested in historical dress fashions and usage of jewelry. Furthermore, the content leads the reader into a new perspective on the subject through a sound dialogue which has been narrated through validated recorded historical data, recorded historical visual information, and logical analysis with reference to scholars of the subject area. -

Muslims in Post-War Sri Lanka: Understanding Sinhala-Buddhist Mobilization Against Them A.R.M

Asian Ethnicity, 2015 Vol. 16, No. 2, 186–202, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2015.1003691 Muslims in post-war Sri Lanka: understanding Sinhala-Buddhist mobilization against them A.R.M. Imtiyaza* and Amjad Mohamed-Saleemb,c aAsian Studies, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA; bUniversity of Exeter, Exeter, UK; cCordoba Foundation, London, UK This study attempts to understand the recent mobilization against the Sri Lankan Muslim community by Sinhala-Buddhist organizations. In doing so, it adds to the discussion about the relationship between second-order minorities and the state and how identities can be manipulated pre- and post-conflict. States, led by majority ethnic groups, may choose to work with second-order minorities out of convenience in times of crisis and then dispose of them afterwards. The article will attempt to look critically at some state concessions to Muslim political leaders who supported successive Sri Lanka’s ruling classes from the independence through the defeat of the Tamil Tigers in 2009. It will also examine the root causes of the Sinhala-Buddhist anti-Muslim campaigns. Finally, it will discuss grassroots perspectives by analysing the question- naire on the anti-Islam/Muslim campaign that was distributed to youth, students, unemployed Muslims and workers in the North-Western and Western provinces. Keywords: monk; Islamophobic; Halal; mobilization; conflict ‘Why, the Muslim community?’ This question is being asked by many people in Sri Lanka and beyond, astonished by the wave of Islamophobic rhetoric and acts of violence against the Sri Lankan Muslim community being undertaken by extreme Sinhala-Buddhists groups (led by Buddhist monks) with tacit support from politicians attacking places of worship and Islamic practices such as Halal food certification, cattle slaughter and dress code. -

Order Book No. (4) of 21.05.2021

( ) (Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 4.] ORDER BOOK OF PARLIAMENT From Tuesday, June 08, 2021 inclusive Issued on Friday, May 21, 2021 Tuesday, June 08, 2021 QUESTIONS FOR ORAL ANSWERS 1. 12/2020 Hon. Hesha Withanage,— To ask the Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Minister of Buddhasasana, Religious & Cultural Affairs and Minister of Urban Development & Housing,—(1) (a) Will he state— (i) the names of the Divisional Secretariat Divisions in the Ratnapura District that were affected by the drought in year 2018; and (ii) if Embilipitiya Divisional Secretariat Division is not included in that list, the reasons for not including it? (b) Will he also state separately on per district basis— (i) the names of the Divisional Secretariat Divisions to which relief was provided under Phase II of the Drought Relief Programme of year 2018; and (ii) the total amount of money that was spent on providing such relief? (c) Will he further state — (i) the circulars that were issued under Phase II of the Drought Relief Programme in year 2018; (ii) out of the aforesaid circulars, the last valid circular that was issued in that regard; (iii) separately on per Divisional Secretariat Division basis, the number of beneficiaries that were selected in the Ratnapura District as per the aforesaid circular, and the total amount that was spent on payment of such relief; and (iv) separately on per Divisional Secretariat Division basis, the number of beneficiaries that were identified in the Ratnapura District as per Circular No. NDR / 2018/03? (d) If not, why? (2) 2. 246/2020 Hon. -

Kurunegala Urban Development Plan

Kurunegala Urban Development plan Volume 01 Urban Development Authority North Western Province 2019 – 2030 Document Information All Rights Reserved. This publication is published by the Urban Development Authority. Any part of this publication without any prior written permission is a punishable offence, in any form of photocopying, recording or any distribution using other means, including electronic or mechanical methods. Plan title : Kurunegala Town Development Plan Planning boundary : Urban Development Authority Area, Kurunegala Gazette number : 2129/96-2019/06/08 Stakeholders : Kurunegala Municipal Council, Kurunegala Pradeshiya Sabha and other institutions. Submitted date : 2019 June Published by, Urban Development Authority - Sri Lanka 6th , 7th and 9th Floors, "Sethsiripaya", Battaramulla. Website - wwwudagove.lk Email - Infoudagov.lk Phone - +94112873637 The Kurunegala Town Development Plan 2019 - 2030 consists of two sections and it is published as Volume I and Volume II. The volume I is comprised of two parts. The first part of the volume I consist of introduction of the development plan, background studies and need of the plan. The second part of volume I consists of vision of the plan, goals, objectives, conceptual plan and development plans. The volume II of the development plan has been prepared as a separate publication. It consists of the regulations for plans and buildings, zoning regulations for the year 2019 – 2030. Supervision Dr. Jagath Munasinghe - Chairman of the UDA Eng. S.S. P. Rathnayake - Director General of the UDA Town Planner, K.A.D. Chandradasa - Additional Director General of the UDA Town Planner, D.M.B. Ranathunga - Deputy Director General of the UDA Town Planner, Lalith Wijerathna - Director (Development Planning) in UDA Town Planner, Janak Ranaweera - Director (Research and Development), UDA ii Preface An urban population in Sri Lanka is rapidly increasing. -

Bringing the Buddha Closer: the Role of Venerating the Buddha in The

BRINGING THE BUDDHA CLOSER: THE ROLE OF VENERATING THE BUDDHA IN THE MODERNIZATION OF BUDDHISM IN SRI LANKA by Soorakkulame Pemaratana BA, University of Peradeniya, 2001 MA, National University of Singapore, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Soorakkulame Pemaratana It was defended on March 24, 2017 and approved by Linda Penkower, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies Joseph Alter, PhD, Professor, Anthropology Donald Sutton, PhD, Professor Emeritus, Religious Studies Dissertation Advisor: Clark Chilson, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies ii Copyright © by Soorakkulame Pemaratana 2017 iii BRINGING THE BUDDHA CLOSER: THE ROLE OF VENERATING THE BUDDHA IN THE MODERNIZATION OF BUDDHISM IN SRI LANKA Soorakkulame Pemaratana, PhD. University of Pittsburgh, 2017 The modernization of Buddhism in Sri Lanka since the late nineteenth century has been interpreted as imitating a Western model, particularly one similar to Protestant Christianity. This interpretation presents an incomplete narrative of Buddhist modernization because it ignores indigenous adaptive changes that served to modernize Buddhism. In particular, it marginalizes rituals and devotional practices as residuals of traditional Buddhism and fails to recognize the role of ritual practices in the modernization process. This dissertation attempts to enrich our understanding of modern and contemporary Buddhism in Sri Lanka by showing how the indigenous devotional ritual of venerating the Buddha known as Buddha-vandanā has been utilized by Buddhist groups in innovative ways to modernize their religion. -

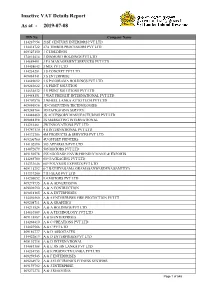

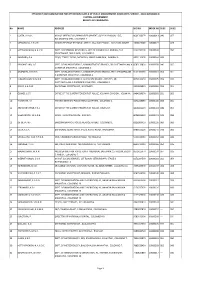

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08 TIN No Company Name 114287954 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 114418722 27A TIMBER PROCESSORS PVT LTD 409327150 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114634832 3 S PRINT SOLUTIONS PVT LTD 114488151 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 114448460 3S ACCESSORY MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 409088198 3S MARKETING INTERNATIONAL 114251461 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 114747130 4 S INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114372706 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 6-7 BATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 A & A CONTRUCTION 409018165 A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 409118887 A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410 A & C CREATIONS PVT LTD 114023566 A & C PVT LTD 409186777 A & D ASSOCIATES 114422819 A & D ENTERPRISES PVT LTD 409192718 A & D INTERNATIONAL 114081388 A & E JIN JIN LANKA PVT LTD 114234753 A & -

Performance Report and Accounts of the District Secretariat

Content No. Chapter Page Number 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Message from the District Secretary/Government Agent 1 1.2 Vision 2 1.3 Mission 2 1.4 Objectives of the District Secretariat 2 1.5 Activities of the District Secretariat 2 1.6 Quality Policy of the District Secretariat 2 1.7 Divisions of the District Secretariat 3 1.8 Information of the District 4 1.9 Divisional Secretariats 4 1.10 District Plan 5 1.11 Organization Chart 6 2 Services provided by the Divisions of the District Secretariat 7 2.1 Administrative Division 7 2.2 District Planning Division 7 2.3 Explosives Division 8 2.4 Media Division 9 2.5 District Divineguma Division 9 2.6 Social Security Division 12 2.7 Measurment & Standard Division 12 2.8 Statistical Division 13 2.9 National Manure Secretariat 15 2.10 Non Government Organization Division 15 2.11 Cultural Division 15 2.12 Buddhist Affairs Division 16 2.13 Social Services Division 18 2.14 Disaster Management Co-ordinating Division 18 2.15 Ceylon Industrial Development Board 18 2.16 Motor Traffic Division 19 2.17 Disaster Relief Division 19 2.18 Internal Audit Division 20 2.19 Engineering Division 21 2.20 Job service centre 25 2.21 Agriculture Division 25 2.22 District Land Use Division 27 2.23 Child Protection Division 27 2.24 Womens‟ Development Division 28 2.25 Land Division 28 2.26 Early Childhood Development Division 29 2.27 Child Rights Division 30 2.28 Investigation Division 30 2.29 Councelling Division 30 2.30 Sports Division 31 2.31 Consumer Affairs Division 31 2.32 Productivity Division 32 2.33 Accounts Division 32 Provision of Annual Estimates 32 Expenditure against Provision 32 General Deposit Account 33 Revenue Account 34 Treasury Imprest Account 34 Provision of Line Ministries and Departments 34 Schedule 02 35 Schedule 03 37 Annual Appropriation Accounts 39 A.C.A - 2 39 A.C.A. -

EB OES Seg B 2014.Pdf

INDEX #NAME1 NICNO GEN. MED SUB1 SUB2 ADDRESS POSTAL TOWN OFFICE OF DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE, (INTER 4400011 KARUNARATHNA, K.N. 813474786V M SIN 046 023 ANURADHAPURA. PROVINCIAL), 4400020 RAJAPAKSHA, R.M.R.S. 816390150V M SIN --- ABS DISTRICT AGRICULTURE TRAINING CENTER, POLONNARUWA. 4400038 NAWARATHNE, N.P.S. 808653850V F SIN ABS ABS C/O. M. SIRIWARDHANA, KAKIRAWA JUNCTION, KAHATAGASDIGILIYA. 4400046 KARUNASINGHE, A.H.I.S.C. 853253880V M SIN 030 032 SEED POTATO FARM, SEETHAELIYA, NUWARAELIYA. 4400054 KODIKARA, K.D.L.E. 792553869V M SIN --- 068 DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE, INTER PROVINCE, HASALAKA. 4400062 VITHANAGE, A.P.K. 862742826V M SIN 041 035 SEED POTATO FARM, SEETHAELIYA, NUWARAELIYA. 4400070 ALAHAKOON, C.Y. 712010428V M SIN --- 035 DEPUTY DIRECTORS OF AGRICULTURE (I.P.) OFFICE, AMPARA. 4400089 BASNAYAKA, B.M.J.N. 882162435V M SIN 047 ABS AGRICULTURE EXTENTION OFFICE, MEDIRIGIRIYA. OFFICE OF DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE (INTER 4400097 EKANAYAKA, E.A.S.N. 872601198V M SIN 059 046 ANURADHAPURA. PROVINCIAL), OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE (INTER 4400100 ABERATHNA, M.R.I. 860734273V M SIN 048 041 ANURADHAPURA. PROVINCIAL), 4400119 AMARASIRI, K.W.M.M. 847120932V F SIN ABS ABS SRI LANKA SCHOOL OF AGRICULTURE, PULIYANKULAMA, ANURADHAPURA. 4400127 GUNAWARDHANA, D.U. 822533736V M SIN --- 041 DISTRICT SECRETARIAT, KOTUWA, MATARA. DEPARTMENT OF EXPORT AGRICULTURE DISTRICT OFFICE, 4400135 JINADASA, S.M.A.S. 730722001V M SIN 048 036 BADULLA. RATWATTA MAWATHA, 4400143 WEERASINGHE, L.N. 897340127V F SIN 035 054 CINNAMON RESEARCH STATION, PALOLPITIYA, THIHAGODA. 4400151 RANAWEERA, P.C. 815684028V F SIN 067 048 CINNAMON RESEARCH STATION, PALOLPITIYA, THIHAGODA. EXTENSION OFFICER, DEPARTMENT OF EXPORT 4400160 BANDARAMENIKE, M.J. -

EB PMAS Class 2 2011 2.Pdf

EFFICIENCY BAR EXAMINATION FOR OFFICERS IN CLASS II OF PUBLIC MANAGEMENT ASSISTANT'S SERVICE - 2011(II)2013(2014) CENTRAL GOVERNMENT RESULTS OF CANDIDATES No NAME ADDRESS NIC NO INDEX NO SUB1 SUB2 1 COSTA, K.A.G.C. M/Y OF DEFENCE & URBAN DEVELOPMENT, SUPPLY DIVISION, 15/5, 860170337V 10000013 040 057 BALADAKSHA MW, COLOMBO 3. 2 MEDAGODA, G.R.U.K. INLAND REVENUE REGIONAL OFFICE, 334, GALLE ROAD, KALUTARA SOUTH. 745802338V 10000027 --- 024 3 HETTIARACHCHI, H.A.S.W. DEPT. OF EXTERNAL RESOURCES, M/Y OF FINANCE & PLANNING, THE 823273010V 10000030 --- 050 SECRETARIAT, 3RD FLOOR, COLOMBO 1. 4 BANDARA, P.A. 230/4, TEMPLE ROAD, BATAPOLA, MADELGAMUWA, GAMPAHA. 682113260V 10000044 ABS --- 5 PRASANTHIKA, L.G. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATIVE BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM A 858513383V 10000058 040 055 GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 6 ATAPATTU, D.M.D.S. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATION BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM 816130069V 10000061 054 051 A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 7 KUMARIHAMI, W.M.S.N. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ACCOUNTS BRANCH, POB 515, SRI 867010025V 10000075 059 070 CHITTAMPALAM A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 8 JENAT, A.A.D.M. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, NEGOMBO. 685060892V 10000089 034 051 9 GOMES, J.S.T. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA DIVISION, KELANIYA. 846453857V 10000092 031 052 10 HARSHANI, A.I. FINANCE BRANCH, POLICE HEAD QUARTERS, COLOMBO 1. 827122858V 10000104 064 061 11 ABHAYARATHNE, Y.P.J. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA. 841800117V 10000118 049 057 12 WEERAKOON, W.A.D.B. 140/B, THANAYAM PLACE, INGIRIYA. 802893329V 10000121 049 068 13 DE SILVA, W.I. -

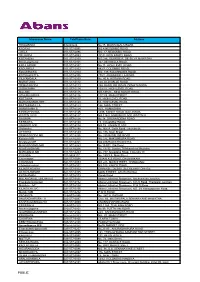

PUBLIC Dehiattakandiya M/B 027-577-6253 NO

Showroom Name TelePhone Num Address HINGURANA 632240228 No.15, MUWANGALA ROAD. KADANA 011-577-6095 NO.4 NEGOMBO ROAD JAELA 011-577-6096 NO. 17, NEGOMBO ROAD DELGODA 011-577-6099 351/F, NEW KANDY ROAD KOTAHENA 011-577-6100 NO:286, GEORGE R. DE SILVA MAWATHA Boralesgamuwa 011-577-6101 227, DEHIWALA ROAD, KIRULAPONE 011-577-6102 No 11, HIGH LEVEL ROAD, KADUWELA 011-577-6103 482/7, COLOMBO ROAD, KOLONNAWA 011-577-6104 NO. 139, KOLONNAWA ROAD, KOTIKAWATTA 011-577-6105 275/2, AVISSAWELLA ROAD, PILIYANDALA 011-577-6109 No. 40 A, HORANA ROAD , MORATUWA 011-577-6112 120, OLD GALLE ROAD, DEMATAGODA 011-577-6113 394, BASELINE ROAD, DEMATAGODA, GODAGAMA 011-577-6114 159/2/1, HIGH LEVEL ROAD. MALABE 011-577-6115 NO.837/2C , NEW KANDY ROAD, ATHURUGIRIYA 011-577-6116 117/1/5, MAIN STREET, KOTTAWA 011-577-6117 91, HIGH LEVEL ROAD, MAHARAGAMA RET 011-577-6120 63, HIGH LEVEL ROAD, BATTARAMULLA 011-577-6123 146, MAIN STREET, HOMAGAMA B 011-577-6124 42/1, HOMAGAMA KIRIBATHGODA 011-577-6125 140B, KANDY ROAD, DALUGAMA, WATTALAJVC 011-577-6127 NO.114/A,GAMUNU PLACE,WATTALA RAGAMA 011-577-6128 No.18, SIRIWARDENA ROAD KESBAWA 011-577-6130 19, COLOMBO ROAD, UNION PLACE 011-577-6134 NO 19 , UNION PLACE Wellwatha 011-577-6148 No. 506 A, Galle Road, colombo 06 ATTIDIYA 011-577-6149 No. 186, Main Street, DEMATAGODA MB 011-577-6255 No. 255 BASELINE ROAD Kottawa M/B 011-577-6260 NO.375, MAKUMBURA ROAD, Moratuwa M/B 011-577-6261 NO.486,RAWATHAWATTA MAHARAGAMA M/B 011-577-6263 No:153/01, Old Road, NUGEGODA MB 011-577-6266 No. -

North Western Province Rural Roads – Project 5

Involuntary Resettlement Due Diligence Report August 2014 SRI: Integrated Road Investment Program North Western Province Rural Roads – Project 5 Prepared by Road Development Authority, Ministry of Highways, Ports and Shipping for the Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 14 May 2014) Currency unit – Sri Lanka rupee (SLRe/SLRs) SLRe 1.00 = $ 0.007669 $1.00 = SLR 130.400 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank AP - Affected Person API - Affected Property Inventory CBO - Community Based Organization CPs - Community Participants CV - Chief Valuer DRR - Due Diligence Report DS - Divisional Secretariat ESDD - Environmental and Social Development Division FGD - Focus Group Discussion GoSL - Government of Sri Lanka GN - Grama Niladari GND - Grama Niladari Division GPS - Global Positioning System GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism INGO - International Non-Government Organizations iROAD - Integrated Road Investment Program IR - Involuntary Resettlement LAA - Land Acquisition Act MOHPS - Ministry of Highways, Ports and Shipping MOU - Memorandum of Understanding MFF - Multi-tranche Financing Facility NGO - Non-Government Organizations NIRP - National Involuntary Resettlement Policy NWP - North Western Province PCC - Project Coordinating Committee PIU - Project Implementing Unit PRA - Participatory Rural Appraisal PS - Pradeshiya Sabha RDA - Road Development Authority SPS - Safeguards Policy Statement This involuntary resettlement due diligence is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Mainstreaming Disruptive Technologies in Public Disclosure Authorized Energy (P166854) FINAL REPORT Kwawu Mensan Gaba, World Bank Brian Min, University of Michigan Public Disclosure Authorized Olaf Veerman, Development Seed Kimberly Baugh, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Acknowledgments The report was prepared by a team led by Kwawu Mensan Gaba, Global Lead – Power Systems in the Energy and Extractive Industries Global Practice (EEXGP), under the guidance of the Senior Director of the EEXGP, Riccardo Puliti. The work took place under the Infrastructure Vice President Makhtar Diop and his predecessor, the Sustainable Development Vice President, Laura Tuck. The report is the result of a collaboration between the World Bank, the University of Michigan (UM), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Center for Environmental Information (NOAA-NCEI) (formerly National Geophysical Data Center), and Development Seed (software developer). Members of the core Bank team included Trevor Monroe and Bruno Sanchez Andrade Nuno. The UM team led by Brian Min included Zachary O’Keeffe, Htet Thiha Zaw, and Paul Atwell. The NOAA-NCEI team led by Kimberly Baugh included Chris Elvidge (NOAA-NCEI), Mikhail Zhizhin, Feng-Chi Hsu and Tilottama Ghosh from Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), University of Colorado. The Development Seed team led by Derek Liu and Olaf Veerman included Vitor George, Alireza Jazayeri, Laura Gillen, Kim Murphy and Ian Schuler. The team is grateful for the guidance received from the peer reviewers, Martin Heger (Economist, GEN05), Tigran Parvanyan (Energy Specialist, ESMAP), Jun Erik Rentschler (Young Professional, GFDRR), Benjamin Stewart (Geographer, GTKM1) and Borja Garcia Senna (Consultant, GEE04).