The Fertility Behaviour of Muslims of Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Role of the Malay Language and the Influence of Extra-Linguistic Factors in Language Usage in Sri Lanka

A Study of the Role of the Malay Language and the Influence of Extra-Linguistic Factors in Language Usage in Sri Lanka Abstract The Sri Lankan Malay language (SLM) has undergone numerous changes in its lexicon and syntax as a result of prolonged contact with the two dominant languages of the country, Sinhala and Tamil as well as English. Therefore it has evolved into a distinct language from the Malay used in the South East Asiatic countries like Malaysia and Indonesia. Along with such linguistic changes SLM has also experienced socio-linguistic changes in terms of its use, role and functions. Since the users of SLM belong to a minority ethnic group in Sri Lanka all of them are bi- or multi-lingual. Numerous language combinations can be traced among the Sri Lankan Malays and this result in complex code switching and mixing which take place among the speakers as well as the dynamic decisions of language choice they make. These language choices and the role and function of SLM are influenced by factors such as local and national ideologies, social and economic class, education, employment, environment, religious fervor and personal beliefs. It is therefore worthwhile to study to what extent extra-linguistic factors influence the language choice(s) of Sri Lankan Malays and how the same factors influence the use of SLM in particular. This study is an attempt to understand this situation and determine how conscious the speech community is about these choices and the changes that occur in the language. The study was conducted through questionnaires and interviews of several families from different socio-economic classes and different geographic locations. -

Ruwanwella) Mrs

Lady Members First State Council (1931 - 1935) Mrs. Adline Molamure by-election (Ruwanwella) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu by-election (Colombo North) (Mrs. Molamure was the first woman to be elected to the Legislature) Second State Council (1936 - 1947) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu (Colombo North) First Parliament (House of Representatives) (1947 - 1952) Mrs. Florence Senanayake (Kiriella) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena by-election (Avissawella) Mrs. Tamara Kumari Illangaratne by-election (Kandy) Second Parliament (House of (1952 - 1956) Representatives) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Avissawella) Mrs. Doreen Wickremasinghe (Akuressa) Third Parliament (House of Representatives) (1956 - 1959) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Colombo North) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Kiriella) Mrs. Vimala Wijewardene (Mirigama) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna by-election (Welimada) Lady Members Fourth Parliament (House of (March - April 1960) Representatives) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Fifth Parliament (House of Representatives) (July 1960 - 1964) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene by-election (Borella) Sixth Parliament (House of Representatives) (1965 - 1970) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Leticia Rajapakse by-election (Dodangaslanda) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte by-election (Balangoda) Seventh Parliament (House of (1970 - 1972) / (1972 - 1977) Representatives) & First National State Assembly Mrs. Kusala Abhayavardhana (Borella) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Dehiwala - Mt.Lavinia) Lady Members Mrs. Tamara Kumari Ilangaratne (Galagedera) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte (Balangoda) Second National State Assembly & First (1977 - 1978) / (1978 - 1989) Parliament of the D.S.R. of Sri Lanka Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Miss. -

Project for Formulation of Greater Kandy Urban Plan (Gkup)

Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development Urban Development Authority Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text September 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. NIKKEN SEKKEI Research Institute EI ALMEC Corporation JR 18-095 Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development Urban Development Authority Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text September 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. NIKKEN SEKKEI Research Institute ALMEC Corporation Currency Exchange Rate September 2018 LKR 1 : 0.69 Yen USD 1 : 111.40 Yen USD 1 : 160.83 LKR Map of Greater Kandy Area Map of Centre Area of Kandy City THE PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PART 1: INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Objective and Outputs of the Project ....................................................... 1-2 1.3 Project Area ............................................................................................. 1-3 1.4 Implementation Organization Structure ................................................... -

Results of Parliamentary General Election - 1947

RESULTS OF PARLIAMENTARY GENERAL ELECTION - 1947 No. and Name of Electoral District Name of the Elected Candidate Symbol allotted No of No of Total No. of Votes No of Votes Votes Polled including Registered Polled rejected rejected Electors 1 Colombo North George R. de Silva Umbrella 7,501 189 14,928 30,791 Lionel Cooray Elephant 6,130 E.C.H. Fernando Cup 501 A.P. de Zoysa House 429 H.C. Abeywardena Hand 178 2 Colombo Central A.E. Goonasinha Bicycle 23,470 3,489 102,772 55,994 T.B. Jayah Cart Wheel 18,439 Pieter Keuneman Umbrella 15,435 M.H.M. Munas House 8,600 Mrs. Ayisha Rauff Tree 8,486 V.J. Perera Elephant 5,950 V.A. Sugathadasa Lamp 4,898 G.W. Harry de Silva Pair of Scales 4,141 V.A. Kandiah Clock 3,391 S. Sarawanamuttu Chair 2,951 P. Givendrasingha Hand 1,569 K. Dahanayake Cup 997 K. Weeraiah Key 352 K.C.F. Deen Star 345 N.R. Perera Butterfly 259 3 Colombo South R. A. de Mel Key 6,452 149 18,218 31,864 P. Sarawanamuttu Flower 5,812 Bernard Zoysa Chair 3,774 M.G. Mendis Hand 1,936 V.J. Soysa Cup 95 Page 1 of 15 RESULTS OF PARLIAMENTARY GENERAL ELECTION - 1947 No. and Name of Electoral District Name of the Elected Candidate Symbol allotted No of No of Total No. of Votes No of Votes Votes Polled including Registered Polled rejected rejected Electors 4 Wellawatta-Galkissa Colvin R. de Silva Key 11,606 127 21,750 38,664 Gilbert Perera Cart Wheel 4,170 L.V. -

SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Sustainable Urban Transport Index Colombo, Sri Lanka

SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Sustainable Urban Transport Index Colombo, Sri Lanka November 2017 Dimantha De Silva, Ph.D(Calgary), P.Eng.(Alberta) Senior Lecturer, University of Moratuwa 1 SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Table of Content Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Background and Purpose .............................................................................................................. 4 Study Area .................................................................................................................................... 5 Existing Transport Master Plans .................................................................................................. 6 Indicator 1: Extent to which Transport Plans Cover Public Transport, Intermodal Facilities and Infrastructure for Active Modes ............................................................................................... 7 Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology ................................................................................................................................ 8 Indicator 2: Modal Share of Active and Public Transport in Commuting................................. 13 Summary ................................................................................................................................... -

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs

DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EI ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. JR 14-142 DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis of Current Public Transport AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis on Current Public Transport TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Railways ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 History of Railways in Sri Lanka .................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Railway Lines in Western Province .............................................................................................. 5 1.3 Train Operation ............................................................................................................................ -

American Institute for Lankan Studies Quarterly Newsletter

American Institute for Lankan Studies Quarterly Newsletter 5/22, Sulaiman Terrace, Colombo 5. Sri Lanka. Tel. 94 11 2508512 tel. 94 11 4513706 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.aisls.org/ United States Director - Dr. John Rogers Executive Director, Colombo Center - Dr. Vagisha Gunasekara _________________________________________________________________________________________________ st 1 Quarter 2019 January-March 2019___ MAIN FEATURES: AILS’ Pilot Digitizing Project AILS Digitization Pilot Lead Success Story Project on SLMA Newspaper The STAR of ISLAM Newspaper & the Jubilee Book Star of Islam & AILS Digitizing Initiative: The STAR of ISLAM Jubilee Book Newspaper and the Jubilee Book Workshop on Digitization Initiative lead by Neel Agrawal of the Center for Research Libraries th 25 January, 2019 Pali Text Society Publications Donation to Rajarata University March 15, 2019 AILS Executive Director, Dr. Vagisha Gunasekera delivering the keynote address – 18.1.2019 The American Institute for Lankan Studies [AILS] included a digitization initiative to preserve endangered material as part of core programming around 2017 focusing on locating, preserving, conserving, digitizing and archiving endangered material which subsequently became a major part of the AILS program activities. Consequently, AILS in collaboration with the Research, Documentation Study and Communications Committee of the Sri Lanka Malay Association [SLMA] worked closely to repair, digitize and conserve endangered historical material of the Malay community, namely; the newspaper series titled The Star of Islam published in Colombo during July 1939 to March 1940 and The Jubilee Book of the Colombo Malay Cricket Club published in February 1924 which needed extensive restoration due its deteriorating state. At the SLMA Founder’s Day annual commemoration & 97th anniversary held on the 18.1.2019, Dr. -

Dress Fashions of Royalty Kotte Kingdom of Sri Lanka

DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KINGDOM OF SRI LANKA . DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KINGDOM OF SRI LANKA Dr. Priyanka Virajini Medagedara Karunaratne S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd. Dedication First Edition : 2017 For Vidyajothi Emeritus Professor Nimal De Silva DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KingDOM OF SRI LANKA Eminent scholar and ideal Guru © Dr. Priyanka Virajini Medagedara Karunaratne ISBN 978-955-30- Cover Design by: S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd Page setting by: Nisha Weerasuriya Published by: S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd. 661/665/675, P. de S. Kularatne Mawatha, Colombo 10, Sri Lanka. Printed by: Chathura Printers 69, Kumaradasa Place, Wellampitiya, Sri Lanka. Foreword This collection of writings provides an intensive reading of dress fashions of royalty which intensified Portuguese political power over the Kingdom of Kotte. The royalties were at the top in the social strata eventually known to be the fashion creators of society. Their engagement in creating and practicing dress fashion prevailed from time immemorial. The author builds a sound dialogue within six chapters’ covering most areas of dress fashion by incorporating valid recorded historical data, variety of recorded visual formats cross checking each other, clarifying how the period signifies a turning point in the fashion history of Sri Lanka culminating with emerging novel dress features. This scholarly work is very much vital for university academia and fellow researches in the stream of Humanities and Social Sciences interested in historical dress fashions and usage of jewelry. Furthermore, the content leads the reader into a new perspective on the subject through a sound dialogue which has been narrated through validated recorded historical data, recorded historical visual information, and logical analysis with reference to scholars of the subject area. -

Distribution of COVID – 19 Patients in Sri Lanka Effective Date 2020-09-11 Total Cases 3169

Distribution of COVID – 19 patients in Sri Lanka Effective Date 2020-09-11 Total Cases 3169 MOH Areas Quarantine Centres Inmates ❖ MOH Area categorization has been done considering the prior 14 days of patient’s residence / QC by the time of diagnosis MOH Areas Agalawatta Gothatuwa MC Colombo Rajanganaya Akkaraipattu Habaraduwa MC Galle Rambukkana Akurana Hanwella MC Kurunegala Ratmalana Akuressa Hingurakgoda MC Negombo Seeduwa Anuradhapura (CNP) Homagama MC Ratnapura Sevanagala Bambaradeniya Ja-Ela Medadumbara Tangalle Bandaragama Kalutara(NIHS) Medirigiriya Thalathuoya Bandarawela Katana Minuwangoda Thalawa Battaramulla Kekirawa Moratuwa Udubaddawa Batticaloa Kelaniya Morawaka Uduvil Beruwala(NIHS) Kolonnawa Nattandiya Warakapola Boralesgamuwa Kotte/Nawala Nochchiyagama Wattala Dankotuwa Kuliyapitiya-East Nugegoda Welikanda Dehiattakandiya Kundasale Pasbage(Nawalapitiya) Wennappuwa Dehiwela Kurunegala Passara Wethara Galaha Lankapura Pelmadulla Yatawatta Galgamuwa Maharagama Piliyandala Galnewa Mahawewa Polpithigama Gampaha Maho Puttalam Gampola(Udapalatha) Matale Ragama Inmates Kandakadu Staff & Inmates Senapura Staff & Inmates Welikada – Prision Quarantine Centres A521 Ship Eden Resort - Beruwala Akkaraipaththu QC Elpiitiwala Chandrawansha School Amagi Aria Hotel QC Fairway Sunset - Galle Ampara QC Gafoor Building Araliya Green City QC Galkanda QC Army Training School GH Negombo Ayurwedic QC Giragama QC Bambalapitiya OZO Hotel Goldi Sands Barana camp Green Paradise Dambulla Barandex Punani QC GSH hotel QC Batticaloa QC Hambanthota -

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka Province District DS Division GN Division Name Code Name Code Name Code Name No. Code Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Sammanthranapura 005 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mattakkuliya 010 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Modara 015 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Madampitiya 020 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mahawatta 025 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthmawatha 030 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Lunupokuna 035 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Bloemendhal 040 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena East 045 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena West 050 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade North 055 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Jinthupitiya 060 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Masangasweediya 065 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 New Bazaar 070 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass South 075 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass North 080 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Nawagampura 085 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Maligawatta East 090 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Khettarama 095 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade East 100 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade West 105 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade South 110 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Pettah 115 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Fort 120 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Galle Face 125 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Slave Island 130 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Hunupitiya 135 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Suduwella 140 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Keselwatta 145 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo -

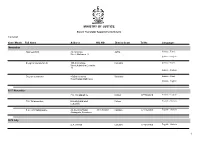

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Radiocarbon Age Dating of 1000-Year-Old Pearls From

Feature Article Radiocarbon Age Dating of 1,000-Year-Old Pearls from the Cirebon Shipwreck (Java, Indonesia) Michael S. Krzemnicki, Laurent E. Cartier and Irka Hajdas The 10th-century Cirebon shipwreck was discovered in 2003 in Indone- sian waters. The excavation yielded an incredible array of archaeological finds, which included pearls and jewellery. Radiocarbon dating of the pearls agrees with the age of the shipwreck, which previously was inferred using recovered coins and ceramics. As such, these are some of the oldest pearls ever to be discovered. Based on this example, the present article shows how radiocarbon age dating can be adapted to the testing of historic pearls. The authors have further developed their sampling method so that radiocarbon age dating can be considered quasi-non-destructive, which is particularly important for future studies on pearls (and other biogenic gem materials) of significance to archaeology and cultural heritage. The Journal of Gemmology, 35(8), 2017, pp. 728–736, http://dx.doi.org/10.15506/JoG.2017.35.8.728 © 2017 The Gemmological Association of Great Britain Introduction Fishermen discovered the wreckage site acci- The discovery of the Cirebon (or Nan-Han) ship- dentally in 2003, at depths greater than 50 m (Lieb- wreck in the Java Sea in 2003 marks one of the ner, 2010) off the northern coast of Java, Indone- most important archaeological finds in Southeast sia, near the city of Cirebon (Figure 2). Excavation Asia in recent years (Hall, 2010; Liebner, 2014; efforts were complicated due to legal uncertainties Stargardt, 2014). Apart from ceramics, glassware as to which companies/entities should be permit- and Chinese coins dating from the 10th century ted to excavate the site, unfortunately leading to AD, the excavation of this ancient merchant ves- a period in which looting of the wreck occurred.