NON-EVENTIVE Mocs in DUTCH and GERMAN 184

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hot Sandwiches Burgers

SANDWICH BOARD MAKE IT DELUXE! INCLUDES: POTATOES, OR RICE, AND CHOICE OF COLESLAW, OR CUP OF SOUP 3.25 | FRIES ONLY 2.25 WE CAN MAKE ANY SANDWICH ON PITA BREAD OR WRAP 0.75 CONEY ISLAND 2.55 Hot dog topped with chili and onions CORNED BEEF & SWISS 6.50 Grilled on Rye bread REUBEN 6.95 BURGERS Our lean, juicy corned beef with Swiss cheese and sauerkraut, on grilled Rye bread ¹/³ lb. Angus Ground Beef, Broiled and Served with Lettuce, TURKEY REUBEN 6.75 Tomato, and Pickle Garnish Our fresh turkey with Swiss cheese and sauerkraut, Make It a Double Burger add 3.50 on grilled Rye bread HAMBURGER COLD HAM OR TURKEY SANDWICH 4.95 5.95 CHEESEBURGER Hand cut fresh, ham or all white meat turkey, 5.50 served with lettuce, tomato and mayo BACON CHEESEBURGER 5.95 MUSHROOM SWISS BURGER 5.95 SLIM HEO 6.95 Grilled ham, Swiss cheese with lettuce and tomato HEO’S BURGER 7.95 ½ lb. hamburger with bacon, mushrooms, grilled FRENCH DIP 6.95 onions, and Cheddar cheese Lean, thin sliced roast beef, served on a French Roll with Au Jus PAULI BURGER 6.50 TUNA SANDWICH 6.25 1/3lb. hamburger with Cheddar cheese, bacon & Albacore tuna served on your choice of toast with lettuce and tomato sunny side up egg CRISPY CHICKEN SANDWICH 6.95 Breaded chicken breast served with Swiss cheese, lettuce and tomato B.L.T. 5.75 Generous portion of bacon with mayo, lettuce and tomato TRIPLE DECKER CLUBS GRILLED CHICKEN PITA 5.95 TRIPLE DECKER CLUB 6.95 Breast of chicken with lettuce and tomato Choice of ham or turkey with bacon, Swiss GYROS SANDWICH 6.25 cheese, lettuce, tomato -

Complete Care Dining Service Inc. Monthly Menu

October Complete Care Dining Service Inc. Monthly Menu Week 1 Am Snack Breakfast Lunch Pm Snack Dinner HS Snack Thursday Coffee/ Tea Scrambled Eggs & Poached Tilapia with Creamy Dill Sauce, Coffee/ Tea Soup of the Day Coffee/ Tea 10/1/2020 Assorted Pastry Fresh Sweet Potatoes, Roasted Broccoli Assorted Ham & Swiss Sandwich w/ Tossed Salad Assorted Pastry Assorted Hot/ Cold Or Snacks Or Snacks Cereal Veal Parmesan Over Parslied Noodles w/ Key Cottage Cheese w/ Fresh Fruit, Freshly West Blend Vegetables Baked Blueberry Muffin Dessert: Assorted Cakes / Pastry Dessert: Assorted Fruit Friday Coffee/ Tea Homestyle Waffles Center Cut Pork Chop w/ Red Pesto, Coffee/ Tea Soup of the Day Coffee/ Tea 10/02/2020 Assorted w/ Maple Syrup Pensylvania Dutch Stuffing, Sunshine Carrots Assorted Chicken Ranch Sandwich on a Roll, Assorted Pastry Assorted Hot/ Cold Or Snacks Caprese Salad Snacks Cereal Liver & Onions, Creamed Corn, Sauteed Or Green Beans Homemade California Cheeseburger w/ Dessert: Assorted Cakes/ Pastry Lettuce, Tomato, & Red Onion Dessert: Assorted Fruit Saturday Coffee/ Tea Scrambled Eggs & Pepper Steak Stir Fry over Classic White Rice, Coffee/ Tea Soup of the Day Coffee/ Tea 10/03/2020 Assorted Pastry Oriental Vegetables Assorted Fresh Roasted Turkey Sandwich, Caesar Assorted Pastry Assorted Hot/ Cold Or Snacks Salad w/ Croutons Snacks Cereal Homemade Three Cheese Macaroni & Or Cheese, Stewed Vegetables Classic Tuna Sandwich, Cole Slaw Dessert: Assorted Pudding Dessert: Assorted Fruit *Menus are Subject to Change. Week 2 Am Snack Breakfast -

Pastries Ice Cream Beverages

MENU PASTRIES Muffins Blueberry, Cranberry, Banana or Bran $2.00 Sticky Bun $2.00 Cinnamon Roll $2.50 Danish Blueberry, Cherry, Apple or Cream Cheese $2.50 Donuts $1.25 Croissant $1.25 Turnovers $2.50 Scones $2.50 Éclair $2.50 Bagels $1.50 Cake and Pie of the Day $3.00 ALSO VISIT SHELL POINT’S OTHER DINING VENUES ICE CREAM Flavors: Coffee, Strawberry, Peach Yogurt, Chocolate, PALM GRILL Vanilla, Mint Chocolate Chip, Butter Pecan BANYAN GRILLE 1 Scoop….…$1.50 2 Scoop….…$2.50 Pint….…$4.00 BREEZEWAY CAFÉ Pint and a Half….…$4.50 Quart….…$6.25 THE CRYSTAL BLEND WAFFLE CONE One scoop….…$2.50 Two scoops….…$3.25 MILKSHAKE $3.75 BEVERAGES Seasonal Healthy Smoothies: Made with seed- to-table, locally sourced fruits and vegetables $6.00 DIN-305-19 Small Coffee: Choose from regular, decaf, special brew or cold brew $1.00 Large Coffee: Choose from regular, decaf, 14990 Shell Point Boulevard special brew or cold brew $1.25 Fort Myers, FL 33908 Open Daily from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. Small Tea: Choose from regular, decaf or green tea $1.00 Phone: (239) 454-2286 Large Tea: Choose from regular, decaf or green tea $1.25 BREAKFAST SALADS FROM THE GRILL Served with French fries, chips, coleslaw, onion rings or fresh fruit Sand Dollar Pancakes: Three made-to-order pancakes Garden Salad: Artisan lettuce, onion, tomato, served with butter and syrup $5.00 carrots, cauliflower, broccoli and a hardboiled egg $6.00 LifeQuest Chicken Wrap: Sautéed chicken breast, served with lettuce, tomato, onion, peppers and pesto Belgium Waffle: One large Belgium waffle, served Turkey -

Biere Birre Apéritifs Aperitivi Weine Vini

Succhi di frutta 3.00 Flasche 0,2 ltr. Fruchtsäfte 3.00 .................................................................................... Flasche 0,2 ltr. 11 Apfelsaft, 100 % naturrein ......................................................................... 3.90 Flasche 0,5 ltr. 12 Orangensaft, 100 % naturrein ..................................................................................................................... 10 Apfelsaftschorle Bevande gassate 3.90 Flasche 0,5 ltr. Limonaden 3.60 (1,2,3) .....................................................................................................Flasche 0,33 ltr. 8 3.90 Zitronenlimonade Flasche 0,5 ltr. 6 Cola (1,2,3,4,11,12) ................................................................................................................................. 3.90 (1,2,3,4,11,12) ......................................................................................... Flasche 0,5 ltr. 7 3.90 Colamix-Getränk .........................................................................................................................Flasche 0,5 ltr. 9 Mineralwasser .............................................................. (1,2,4,10) 3.60 32 Mineralwasser ohne Kohlensäure Flasche 0,2 ltr. 14,15,13 Schweppes Bitter Lemon, Tonic Water, .............................................................. Ginger Ale Schweppes Bitter Lemon, Tonic Water, Ginger Ale Biere Birre 1 Bier hell (A) ......................................................................... Flasche 0,5 ltr. 4.20 2 Hefe-Weißbier -

Starters Sandwiches Side Items Burgers

An 18% gratuity is added to checks for parties of five or more. Starters Chicken Tenders 5.30 Mozzarella Sticks 5.00 Five golden brown chicken tenders served with Six breaded mozzarella sticks served with marinara honey mustard, BBQ, ranch, or sweet-n-sour sauce. sauce or ranch dressing. Onion Rings sm. 2.50/ lg. 4.00 Soups 3.00 Our rings are freshly-prepared and are battered Ask your server for the soup of the day and fried until crisp and golden. Cup of Brunswick Stew 3.00 Available after 11 a.m. Chili Cheese Fries 4.55 Tossed Salad 3.30 A plate of our golden fries smothered with (with an entrée or sandwich only 2.80) homemade meat chili and your choice of cheese. Burgers The beef for our burgers is ground daily at Cliff’s Meat Market from 100% chuck, char-grilled, and served with lettuce, tomato, and mayo on a sesame seed bun with chips and a pickle spear. Raw and grilled onions are available for no extra charge. Substitute French Fries—1.00, onion rings — 1.50 or available veggies— 1.50 Hamburger 4.30 The Mixed Grill Burger 5.60 Our cheese burger served with a slice of Cheeseburger 5.10 sugar cured ham. Our burger with the choice of cheddar, Swiss Blue Cheese Burger 5.60 provolone, or American cheese. Our hamburger served with our special Bacon Cheeseburger 5.60 blue cheese mix on the side. Two strips of bacon served atop our Chili Cheese Burger 5.80 cheeseburger with your choice of cheese. -

Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 Certificate in German Minimum Core Vocabulary

Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 Certificate Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 Certificate in German (KGN0) Minimum core vocabulary list First examination 2014 Pearson Education Ltd is one of the UK’s largest awarding organisations, offering academic and vocational qualifications and testing to schools, colleges, employers and other places of learning, both in the UK and internationally. Qualifications offered include GCSE, AS and A Level, NVQ and our BTEC suite of vocational qualifications, ranging from Entry Level to BTEC Higher National Diplomas. Pearson Education Ltd administers Edexcel GCSE examinations. Through initiatives such as onscreen marking and administration, Pearson is leading the way in using technology to modernise educational assessment, and to support teachers and learners. References to third-party material made in this document are made in good faith. Edexcel does not endorse, approve or accept responsibility for the content of materials, which may be subject to change, or any opinions expressed therein. (Material may include textbooks, journals, magazines and other publications and websites.) All the material in this publication is copyright Publications code UG034088 © Pearson Education Limited 2012 Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 Certificate in German Minimum core vocabulary The following vocabulary list is intended to help you plan work in relation to your programmes of study. Assessment tasks targeted at grades G to C will be based on this vocabulary list, although they may include some unfamiliar vocabulary. Occasional glossing of individual words may occur in the examinations, although this will be avoided whenever possible. As well as specified vocabulary, students will be expected to have knowledge of numbers, times, days of the week, months etc. -

Cooking Until Cheese Is Melted and Lightly Browned

Delicious Sandwich Recipes Delicious Sandwich Recipes Collection of Delicious Sandwich Recipes Ebook with Master Resale and Redistribution Rights!! Legal Notice:- You have full rights to sell or distribute this document. You can edit or modify this text without written permission from the compiler. This Ebook is for informational purposes only. While every attempt has been made to verify the information provided in this recipe Ebook, neither the author nor the distributor assume any responsibility for errors or omissions. Any slights of people or organizations are unintentional and the Development of this Ebook is bona fide. This Ebook has been distributed with the understanding that we are not engaged in rendering technical, legal, accounting or other professional advice. We do not give any kind of guarantee about the accuracy of information provided. In no event will the author and/or marketer be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential or other loss or damage arising out of the use of this document by any person, regardless of whether or not informed of the possibility of damages in advance. Contents - 1 - Delicious Sandwich Recipes Contents ABC Sandwich ALL-AMERICAN BARBECUE SANDWICHES All American Club Sandwich Acapulco Fishburgers Anytime Apple Muffinwiches Alaska Salmon Sandwich Stuffer Alaska Salmon Salad Sandwich Alan's Special Sandwich Apple-Mustard Sliced Ham Antipasto Sandwich Asian Turkey Burgers Avocado and Chicken Tortas Avocado Bacon Sandwiches Avocado Chicken Melt Avocado Chicken Salad Sandwich -

Croque Madame Muffins Cheese, Ham, and Egg Sandwich Muffins

Croque Madame muffins Cheese, ham, and egg sandwich muffins Makes 4 Croque Monsieur is essentially a toasted cheese and ham sandwich. Put a fried egg on top and you’ve got a Croque Madame (the egg is supposed to resemble a lady’s hat). What makes the difference between a toasted cheese and ham sandwich and a Croque Monsieur is the cheese— in a Croque Monsieur it comes in the form of a creamy cheese sauce. And boy, does this make a difference! My version of Croque Madame uses the bread as a muffin cup to contain the delicious cheese sauce and egg. Great as a snack, or have it with a green salad and fries, as they serve it in French cafés. For the Mornay (cheese) sauce: 1 tbsp butter • 1 tbsp all-purpose flour • ¾ cup plus 1 tbsp milk, lukewarm • ½ tsp Dijon mustard • ½ tsp nutmeg • ¼ cup grated Gruyère or mature Comté cheese (or a strong hard cheese like Parmesan or mature Cheddar) • salt and pepper • 6 large slices of white bread, no crusts • 3 tbsp butter, melted • 2½ oz ham, cut into cubes or thin strips • 6 small eggs TO MAKE THE SAUCE: Melt the butter in a pan over a medium heat. Add the flour and beat hard until you have a smooth paste. Take off the heat and leave to cool for 2 minutes, then gradually add the milk, whisking constantly. Place the pan back over a medium heat, add the mustard and nutmeg, and simmer gently for 10 minutes, whisking frequently to stop the sauce burning on the bottom of the pan. -

Spring Break

• * * March 2012 Menu * * * Des Moines Middle School Menu Menus are subject to change without notice This menu can also be found on the web www.dmschools.org Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Assorted Fruits and This institution is an equal 1 Hot Choice 2 Hot Choice Vegetables are available daily opportunity provider Pizza Cheese Bread w/Marinara Little Smokies Sauce Cheeseburger on a Bun Grilled Chicken on a Bun Breaded Chicken on a Bun Mini Corn Dogs A choice of Skim, 1% or Cold Choice Cold Choice Yogurt Box Fat Free Chocolate milk is Yogurt Box Triple PB & J Sandwich offered with each meal. Triple PB & J Sandwich Turkey Sandwich Ham Sandwich Chef Salad w/Cheese Chef Salad w/Cheese Chef Salad w/Ham & Cheese Chef Salad w/ Turkey & Cheese 5 Hot Choice 6 Hot Choice 7 Hot Choice 8 Hot Choice 9 Hot Choice Pizza Pizza Pizza Pizza Cheese Bread w/Marinara All Beef Hot Dog on a Bun Beef Taco Hamburger on a Bun Macaroni & Cheese Sauce Grilled Chicken Patty on a Bun Breaded Chicken on a Bun Chicken Nuggets Tomato Soup w/Grilled Cheese Hamburger on a Bun Bean and Beef Burrito Cheeseburger on a Bun Savory Pork w/Gravy Breaded Chicken on a Bun Meatball & Mozzarella Sub Mini Corn Dogs Cold Choice Cold Choice Cold Choice Cold Choice Yogurt Box Yogurt Box Yogurt Box Yogurt Box Cold Choice Triple PB & J Sandwich Triple PB & J Sandwich Triple PB & J Sandwich Triple PB & J Sandwich Yogurt Box Turkey Sandwich Ham Sandwich Turkey Sandwich Ham Sandwich Triple PB & J Sandwich Chef Salad w/Cheese Chef Salad w/Cheese Chef Salad w/Cheese Chef Salad w/Cheese -

Amped-Up Ham Sandwiches It’S Time to Get Creative with Your Lunch

Activity Amped-Up Ham Sandwiches It’s time to get creative with your lunch. Ham is a delicious and nutrient-rich form of pork, and a perfect centerpiece for sandwiches. You can buy deli ham, cook a whole ham and slice it, or even use canned ham! On its own, ham has great nutritional value. It’s an excellent source of protein, which plays a role in building muscles. Ham is also a good source of zinc, which helps support your immune system, and other vitamins that give you energy and keep your body moving. When you add vegetables and dairy products like cheese, then wrap your sandwich in a whole grain package, you’re creating a more balanced meal. Below are some ideas for “amped-up” ham sandwiches sure to tickle your taste buds and fuel your health. Ham Sandwich Ideas • The Classic: Place slices of ham and Swiss cheese on whole grain bread and top with lettuce, tomato, and pickles. Spread mustard on the bread for extra flavor! • Pita-Licious: Fill pita pockets with ham, sliced apples, cucumbers, and honey mustard for a perfect combination of sweet, salty, and sour. • Grill It: Layer ham, cheddar cheese, and avocado slices on your favorite bread, spread a thin layer of butter on the outsides of the bread, and grill to melty deliciousness! • Hawaiian Ham Burrito: Stir together chopped ham, lowfat mayo, pineapple chunks, and diced red onion. Serve in a whole wheat wrap. Design Your Own Ham Sandwich Directions: Create a brand new ham sandwich that includes at least two of the following add-ons: vegetables, whole grains, and dairy. -

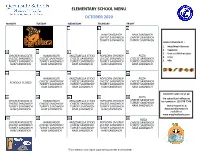

Elementary School Menu October 2020

ELEMENTARY SCHOOL MENU OCTOBER 2020 MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY 1 2 HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH LUNCH CONSISTS OF : 1. Meat/Meal Alternate 2. Vegetable 5 6 7 9 8 3. Fruit or 100% fruit juice CHICKEN NUGGETS HAMBURGER MOZZARELLA STICKS POPCORN CHICKEN PIZZA 4. Grain CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH 5. Milk HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH 12 13 14 15 16 HAMBURGER MOZZARELLA STICKS POPCORN CHICKEN PIZZA CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH SCHOOLS CLOSED TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH STUDENT LUNCH IS $2.60 19 20 21 22 23 PIZZA The school lunch office can CHICKEN NUGGETS HAMBURGER MOZZARELLA STICKS POPCORN CHICKEN CHEESE SANDWICH be reached at 516-678-7548 CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH Online Payments & HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH Account Information is available at www.myschoolbucks.com 26 27 28 29 30 PIZZA CHICKEN NUGGETS HAMBURGER MOZZARELLA STICKS POPCORN CHICKEN CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH CHEESE SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH TURKEY SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH HAM SANDWICH This institution is an equal opportunity provider and employer. . -

Speisekarte-Sperl-Orig.Pdf

The Cafe Sperl History 1880, the coffeehouse was built according to the design of the ring road architects Gross and Jelinek for Jacob Ronacher. That same year, the cafe Ronacher was bought by the family „Sperl“ and in 1884 Adolf Kratochwilla become the owner , who retained the now well-established name „Cafe Sperl“ . In the Sperl „lived“ architects, artists, musicians, actors, singers, generals and high officials. Among the regulars were the Archdukes Josef Ferdinand and Karl Ferdinand and chief of staff of Conrad Hötzen- dorf. (In the summer of 1914, Conrad was one of the main supporters of an immediate war against the Kingdom of Serbia in response to the assassination of the heir in Sarajevo) The visitor circle characteri- zied the Cafe Sperl as an artist and military Cafe. Despite the divergent political and social differences the coexistence was possible. Of particular note is the 1895 established „Hagen society“. From parts of Hagen society and the so-called seven-Club („C7“), Josef Maria Olbrich, Josef Hoffmann, Frederick Pilz, Kolo Moser, Max Kurzweil, Leo Kainradl and Adolf Karpellus 1896/1897 formed the Secession The Hagenbund was dissolved in the war winter of 1942. Around 1890, the operetta inspired the Viennese and just like then and now, the Raimund Theater and the Theater an der Wien were the main stages and the crowd favorites. The Cafe Sperl was the meeting place for stars and composers like Lewinsky, Girardi, Eysler, case, Zeller, Heuberger, Millöcker, Lehar and Kalman. These artists shaped 1930‘s lifestyle on stage and in the Sperl. At Cafe Sperl our visitors have and always will be „regulars“ in the best sense of the word and tourist included in this process and therefore come back.