The Value of Open Standards to Transportation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1.0: Purpose and Need

Chapter 1.0: Purpose and Need A. INTRODUCTION On October 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy made landfall, greatly impacting the east side of Manhattan and highlighting the need for the City of New York (the City) to increase its efforts to protect vulnerable populations and critical infrastructure during extreme coastal storm events (the 100- year flood events with Sea Level Rise projections to the 2050s1), referred to herein as the design storm event. Hurricane Sandy, a presidentially declared disaster, caused extensive coastal flooding, resulting in significant damage to residential and commercial property, open space, and critical transportation, power, and water and sewer infrastructure, which in turn affected medical and other essential services. As part of its plan to address vulnerability to such major flooding, the City is proposing the East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR) Project, which involves the construction of a coastal flood protection system along a portion of the east side of Manhattan (see Figure 1.0-1) and related improvements to City infrastructure (the proposed project). The area that would be protected under the proposed project (the protected area) includes lands within the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) 100-year special flood hazard area (SFHA), as well as those projected to be within the 100-year flood hazard area in the 2050s, taking into account the 90th percentile projection for sea level rise (see Figure 1.0-2). This includes portions of the Lower East Side and East Village neighborhoods, Stuyvesant Town, Peter Cooper Village, as well as East River Park and Stuyvesant Cove Park. Within the project area, the City is proposing to install a flood protection system generally located within City parkland and streets, which would consist of a combination of floodwalls, levees, closure structures (e.g., floodgates), and other infrastructure improvements to reduce the risk of flooding. -

Important Phone Numbers Sick Call Numbers

Road Operations (continued) Linden Yard, 1500 Linden Blvd., Brooklyn, NY 11212 RCI responsibilities typically include pre-inspection; repairs; performing weekly, monthly, and annual Telephone: 347-643-7884 Fax: 347-643-7889 inspections of the Vacuum Trains; and periodic inspections of the Pump Train. RCIs at the 239th, Linden Yard serves as a major fabrication shop for the Division of Track. The crews assemble Corona, 207th, Coney Island and 36th Street Yards pre-service and repair eight Refuse Collection replacement track panels and other rail components critical to mainline integrity. The Linden Yard trains daily. These trains travel throughout the system, pick up refuse from stations, then return to has track connections to the IRT New Lots Line and the BMT Canarsie Line. Yard moves require their respective yards for unloading by a Contractor managed by the NYC Transit Asset Recovery using diesel-powered horses exclusively, because Linden Yard does not have an electrified third Unit. DCE Work Equipment Road Operations works closely with Rapid Transit Operations Sub rail. There is also a track connection to the Long Island Rail Road’s Bay Ridge Branch. This LIRR Division “C” and track personnel to assemble a variety of work cars and locomotives to build work connection is one of two from NYC Transit to the mainline United States rail network (the BMT West train consists in accordance with the daily manifest. Division “C” provides crews for these trains End Line is the other). used by several divisions within NYC Transit. The rolling stock is the same width as “A” Division Linden Yard is a staging/dumping area for the Vacuum Train. -

9802 Foster Ave Forsalesetup&Comparables.Xlsx

CANARSIE CORNER MIXED USE BROOKLYN INVESTMENT. FOR SALE: ASKING PRICE Submit all offers! $1,200,000 Seller will Accept all Cash: $1,000,000 5.41% Cap Rate Proforma: 8.3% 13% = Long Term Projected Proforma Future Cash On Cash ROI (Before CC&MCI) 5% Immediate Proforma Cash on Cash ROI Proforma: 13% 25% = Long Term Projected Proforma Future Cash On Cash ROI (Before CC&MCI) True Initial Cash On Cash ROE Return on Equity Investment Net Income PLUS 9% Principal Reduction Proforma: 17% 28% = Long Term Projected Proforma ROE True Initial Cash On Cash Return on Equity Investment Including Net Income After Debt Service PLUS Add Back Vacancy Allowance, Collection Loss, Replacement Reserves, TILC, 5% Management Fee 10% Plus Amortization Principal Reduction From Debt Service 13 = GRM Gross Income Multiplier Proforma GRM xRR: 16.22 14.9215 = Long Term Projected Gross Rent Multiplier $418 = Price Per Square Foot $333,333 = Price Per Unit $219 Price Per Maximum Usable Buildable Square Footage and Air Rights as Residential Building $438 Price Per Square Foot of Land Area Square Feet Square Feet Subject Property Address Being Sold, Location and Description Property Address: 9802 Foster Avenue Neighborhood: Neighborhood Section of City, State, Zipcode: Canarsie Brooklyn, NY 11236 Location: (SE Corner of East 98th Street and Foster) Block & Lot # Block: 8148 Lot: 28 DESCRIPTION: Property Is A 2 Story, Three Unit Mixed Use Building Located In The Canarsie Neighborhood Of Brooklyn. The Property Consists Of Two Residential Apartments Totaling 1,445 Square Feet, A 945 Square Foot Commercial Unit Plus A Garage. CERTIFICATE OF OCCUPANCY INFORMATION: CERTIFICATE OF OCCUPANCY READS: No C of O or Icards Available. -

East Side Coastal Resiliency Project: Draft Scope of Work to Prepare a Draft Environmental Impact Statement

East Side Coastal Resiliency Project: Draft Scope of Work to Prepare a Draft Environmental Impact Statement October 30, 2015 East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR) Project Draft Scope of Work East Side Coastal Resiliency Draft Scope of Work to Prepare a Draft Environmental Impact Statement October 30, 2015 CEQR No: 15DPR013M NEPA Lead Agency: New York City Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Director: Dean Fuleihan NEPA Lead Agency Calvin Johnson, Assistant Director, CDBG Disaster Contact: Recovery SEQRA/CEQR Lead New York City Department of Parks & Agency: Recreation Commissioner: Mitchell J. Silver, FAICP SEQRA/CEQR Lead Owen Wells, Director of Environmental Review Agency Contact: Preparers: New York City Office of Management and Budget New York City Department of Parks & Recreation With the Assistance of Hazen and Sawyer 498 Seventh Avenue, 11th Floor New York, NY 10018 AKRF, Inc. 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016 2 East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR) Project Draft Scope of Work TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 6 2 Background of the Proposed Action ..................................................................................... 7 3 Purpose and Need of the Proposed Action ........................................................................... 9 4 Environmental Review Process ........................................................................................... 10 5 Potential Regulatory Permitting, -

Page 1 Scale of Miles E 177Th St E 163Rd St 3Rd Ave 3Rd Ave 3Rd a Ve

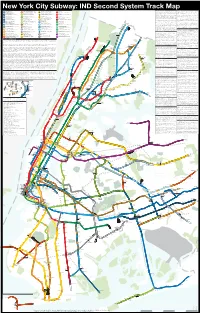

New York City Subway: IND Second System Track Map Service Guide 1: 2nd Avenue Subway (1929-Present) 10: IND Fulton St Line Extensions (1920s-1960s) 8th Av, Fulton St Exp. 6th Av Local, Rockaway, Staten Island Lcl. 2 Av Lcl, Broadway Exp, Brighton Beach Locl. 7th Av Local. The 2nd Ave Subway has been at the heart of every expansion proposal since the IND Second The IND Fulton St Subway was a major trunk line built to replace the elevated BMT Fulton St-Liberty Ave 207 St to Jamaica-168 St, Bay Ridge-86 St to Jacob Riis-Beach 149 St. 2 Av-96 St to Stillwell Av-Coney Island. Van Cortlandt Park-242 St to South Ferry. System was first announced. The line has been redesigned countless times, from a 6-track trunk line. The subway was largely built directly below the elevated structure it replaced. It was initially A Queens Village-Sprigfield Blvd. H Q 1 line to the simple 2-track branch we have today. The map depicts the line as proposed in 1931 designed as a major through route to southern Queens. Famously, the Nostrand Ave station was with 6 tracks from 125th St to 23rd St, a 2-track branch through Alphabet City into Williamsburg, 4 originally designed to only be local to speed up travel for riders coming from Queens; it was converted to 8th Av, Fulton St Exp. Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown Local. 2 Av Lcl, Broadway Exp, Brighton Beach Locl. 7th Av Exp. tracks from 23rd St to Canal St, a 2-track branch to South Williamsburg, and 2 tracks through the an express station when ambitions cooled. -

Rapidly Increasing Press-In Piling Projects in New York Metropolitan Area (Part 1)

Volume 6, Issue 1 March 2021 Case-History Rapidly Increasing Press-in Piling Projects in New York Metropolitan Area (Part 1) Takefumi Takuma GIKEN LTD., c/o Giken America Corporation Masashi Nagano Giken America Corporation INTRODUCTION The Giken America Corporation is a U.S. subsidiary of GIKEN LTD. that was established in Orlando, Florida back in 1999. It had undertaken numerous sheet and pipe pile installation work as a speciality piling contractor using GIKEN’s machines to showcase the advantages of the press-in piling method in North America. In 2010, it started to focus more on promoting its press-in piling technology to project owners and consultants while making GIKEN’s press-in piling machines available for rental and sales for contractors. In March 2019, it opened a New York City office as its new headquarters in the Americas, intending to focus on the most populous region of North America. It also started collaboration with Mueser Rutledge Consulting Engineers (MRCE), a famed New York City-based geotechnical consultant, and Heavy Metal Rentals (HMR), a well-established construction equipment rental company based in Long Island, New York. Three press-in piling projects with their approximate locations shown in Fig. 1 will be discussed as part of GIKEN’s achievements in the New York Metro region. Earth Retaining Walls for Long Island Expressway/Cross Island Parkway Widening When the Perini Corporation, then a New York-based heavy civil contractor, undertook an expressway widening and bridge replacement project in Long Island in New York in 2000. They submitted value engineering (VE) change proposals to the project owner, the New York State Department of Transportation, to build 10.5m (35ft) high self-standing pressed- in pipe pile walls for earth retaining at two different locations on the project in lieu of very large H-section soldier piles with precast concrete panels. -

INDEX' American Jewish Tercentary * Andrada Statue Dedication Barber

INDEX' American Jewish Tercentary * Andrada Statue Dedication Barber Shop Contest Basketball Tournament (Brownsville Rec. Center) Bathing & Swimming Season Beach Erosion Control (South Beach) Boxing Program Brownsville Recreation Center Concerts — City Symphony, Naumburg, "Pop" Coast Guard World War II Memorial (Battery Park) Dance Festivals Downing Memorial Stadium Egg Rolling Contest Fif^and Drum Competition Fishing Coatest (Nathan's Famous) A<SS Fiorina Lasker Foundation Golf Courses Opening Gymnastic Championships Ice Skating on Lakes Marionette Theatre Monuments — Robert Fulton Music and Dancing in City Parks -(Name Band and Square Dances) Parkway Resurfacing Permits - Golf and Tennis PLAYGROUNDS — #6^0(Van Dyke), 639 (Redfern), 638 (Hammels), 637(G.Washington), 636,(St. John's add. area) PS 260 (part of Breukelen Houses Plan) #635, 63^, 633, 632, 631 630, 629, 628 Poster Contest Recreational Facilities «4 «-«.... -,- (over) St. Mary's Rec. Center Weight Lifting, Open House Week, Swimming Meet Smith Memorial Fund Wollman Memorial Skating.Rink - Ice & Roller Skating DEPARTMEN O F P ARK S ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK REGENT 4-1000 "lit - • . FOR RELEASE SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 20. l-l-l-30M-505074(55) 114 ~ /A'3 , L- The Department of Parks announces that the Altman Foundation, through its president John S, Burke, has made a generous gift to the City of New York for the purpose of rehabilitating and improving the Children's Pony Track in Central Park. The Pony Track is a source of enjoyment to thousands of children each year. It is located at 63d Street Just off Fifth Avenue adjacent to and south of the Central Park Zoo. It has long been in urgent need of rehabilitation, but the limited funds avail- able in the Department's annual budgets have delayed the scheduling of this work. -

But Rather As a Basis for Study

DO4111,41tP4T PPRIIMPI EF 003 286 ED 030 276 City. Concept forDiscussion. The EducationalPark in New York New York CityBoard of Education.Brooklyn. N.Y. Pub Date Apr 65 Note -23p. -$0.25 He -$1.25 *Educational Parks. EDRS Price MF Schemes. *Criteria.Distance. Economics. Descriptors -CommunityRelations. *Conceptual School Location.*Site Selection.Transportation parks--(1) the plan for threedifferent kindsof educational A study outline (3) the pyramidtype ispresented. Each is horizontal type.(2) the verticaltype. and basis forstudy and discussed, not asdefinitive proposals.but rather as a thet. hope thatitwill stimulatepublic and discussion. Thestudy was writtenin educational parks. leading to thecreation ofthe first urban professional discussion be used forselection of a sitefor an Also included is asection on:he criteria to educational park.(RK) c961 "Ificke )1110A M3N dO A.1.13 3111 dO NOLLVD1103 dO C131/00 N i ssnDsIa1:10d.Lci aDNOD ow .: .,, . !!!!!!!!!!!, LI ° imastwavoma losallielinnalitililat 4111111111211/1/1111161111P.'' 1/818.1-1;;;lean moll al 111:::1114117.17:411:iii 111:111:47 al"..11111111.1.18.111.1" Rs; itioNst 11411111411811.81, liii .011; ; ,11211MOMOr liMMONOMME.0. MIMMUSEMOMMr- OMMOMMEMOOMmisw--... OMMEMOMMow:I.enemallink !OSPIPT:olossMOOMMMOMM1 imommumommomoommtm..OMEMMIIMMOMMOMMOWIR ommumummummumumemoutwommommommmmommuld vimmummwommummemoeay INWOMMOMMOMMMOMMEMP IMMOIMMOMMOMMOMMOMMOW simMEMOOMMIONEMMEMMEr, IMMUMMOMMMOMORMSOM ummummommommmemom.JcAs somjummommommEmmow./m. mosommumms,Jcimat--cream ---o04AMOIMIR 0110d 10 MUM" A1111SSDIN ION 00 01MS 10IL)fl00 MO %MO 111511d11 11011111010 10 NOSild 91011110 10 ?MIA 10SINN .11 911100110 SH BORID00 SIM 111 WON 01M1111 S/ADM OD00011111 1111 BOARD OF EDUCATION James B. Donovan, President Lloyd K. Garrison, Vice-President Joseph G. Barkan Aaron Brown Thomas C. Burke Alfred A. Giardino Morris Iushewitz Clarence Senior Mrs. -

`New York City Transit

` New York City Transit R47 Locomotive Welcome to Work Equipment Work Equipment is part of the Division of Car Equipment in the Crane Department of Subways. As a centralized unit, we coordinate our activities more efficiently than as separate entities. We have three responsibility centers at five support sites. We are “the home of non-revenue cars,” because we have 569 pieces of varied non-revenue rolling stock. In the next few pages, you will find descriptions of how we work and where we operate. The contributions of every employee and piece of equipment make our operations successful, and keep New York City and its vast subway system moving 24/7. As a veteran NYC Transit employee, I am proud of our work and look forward to Emergency Dispatch Vehicle (EDV), working beside you. the most frequently used vehicles in Work Equipment. Welcome to our team. Sincerely, Joseph Ragusa Jr. General Superintendent Division of Car Equipment Work Equipment Rail Adhesion Train Contents: • Work Equipment Organization Chart/Responsibilities 1 • All About Work Equipment Sites and Services 2-4 • Important Phone Numbers 4 Tank Car (front) Weld Car ( at right) • FASTRACK Support 5-6 • DCE Maintenance Facilities, NYC Transit Learning Center Addresses and Travel Information 7-8 • DCE Work Equipment 9-10 • The New Equipment 11-12 • Did You Know? Facts & Figures about the Work Equipment Group 13 Pump Car Cover: The Vacuum Train removes track debris, which reduces the number of track fires. Work Equipment Organization Chart All About DCE Work Equipment Sites and Services Westchester Locomotive Shop Chief Mechanical Officer 1650 Eastchester Road, Bronx, NY 10461 Telephone: 347-694-3775 Fax: 347-694-3797 The Westchester Locomotive Shop opened in 1982 as the Pelham Diesel Shop, but was renamed when the facility began maintaining electric locomotives as well as diesel locomotives. -

Urbahn Architects Completes Renovation of Morgan Avenue Subway Station, Brooklyn May 16, 2017 - Design / Build

Urbahn Architects completes renovation of Morgan Avenue subway station, Brooklyn May 16, 2017 - Design / Build Morgan Avenue Station - Brooklyn, NY Brooklyn, NY The New York City architectural and planning firm of Urbahn Architects has completed the renovation of the historic Morgan Ave. subway station house for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Serving the L train line, the Morgan Ave. station house is located on the west side of Bogart St., at the intersection of Harrison Place, in the East Williamsburg section. MTA served as project manager as well as structural, civil, and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) engineer for the upgrades. General contractor was Double M Construction. “The Morgan Ave. station provides crucial public transportation connection to an up-and-coming Brooklyn neighborhood. The project improved the station’s appearance, increased passenger comfort, and upgraded the building’s structural system,” said Urbahn principal Natale Barranco, AIA, LEED AP. “The renovation of the 2,400 s/f façade has brought the historic structure, originally built in 1928, to its former attractive architectural form.” Opened on July 14, 1928, as part of an extension of the BMT Canarsie line, the Morgan Ave. station serves the eastern section of the trendy Williamsburg neighborhood, an area that is increasingly popular with young professionals due it its diverse ethnic population, numerous restaurants and bars, availability of rental apartments, and very easy commute to Manhattan via the L train. Urbahn associate Nandini Sengupta, LEED AP, said, “The renovation included replacement of the entire 400 s/f brick and limestone façade, repairs to the roof, and installation of a new framed entrance with transom windows, exterior LED lighting, and exterior signage.” The project team installed a new façade that features brick set in a geometrical pattern and a limestone base and apron. -

The Bulletin AVENUE a ENTRANCE OPENS/ Published by the Electric Railroaders’ CANARSIE LINE UPDATE Association, Inc

ERA BULLETIN — DECEMBER, 2019 The Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 62, No. 12 December, 2019 The Bulletin AVENUE A ENTRANCE OPENS/ Published by the Electric Railroaders’ CANARSIE LINE UPDATE Association, Inc. P. O. Box 3323 by Subutay Musluoglu Grand Central Station New York, NY 10163 (Photographs by the author) For general inquiries, We have been periodically visiting the Ca- enough that they could possibly be opened or Bulletin submissions, narsie Line this year, as MTA New York City before the end of the year. contact us at bulletin@erausa. org Transit (NYCT) continues to reconstruct the Some background is in order. The 1 Av sta- or on our website at 14th Street Tubes to remedy the damage tion suffers from two related issues — con- erausa. org/contact inflicted by Superstorm Sandy in 2012. Previ- strained capacity and location. As of 2018, Editorial Staff: ous installments in this series appeared in this station was used by 21,000 average the February and September Bulletins. weekday riders, the 65th busiest station in Jeffrey Erlitz Editor-in-Chief While work continues on the under-river the entire subway system. As such, the build- tubes, it has been accompanied by a series ing of these new entrances should be exam- Ronald Yee of capacity improvements at several subway ined in the larger historical context of the de- Tri-State News and Commuter Rail Editor stations on the Canarsie Line as well as ad- velopment of the Lower East Side and be- jacent lines in Brooklyn and Queens. Fare yond, as it realizes a transit need that long Alexander Ivanoff North American and control areas are being rearranged, long- predates the current Canarsie Line rehabilita- World News Editor closed mezzanines and street access stair- tion project. -

A Quantification Analysis on Potential Use of Recuperated Regenerative Braking Energy from NYCT Subways Into Charging Electric Buses

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2018 A Quantification Analysis on otentialP Use of Recuperated Regenerative Braking Energy from NYCT Subways into Charging Electric Buses AHMED S. RAHMAN CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/890 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________________________ A Quantification Analysis on Potential Use of Recuperated Regenerative Braking Energy from NYCT Subways into Charging Electric Buses The City College of New York Master’s Thesis in Electrical Power Engineering AHMED S. RAHMAN _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Department of Electrical Engineering Grove School of Engineering The City College of the City University of New York New York, USA A Quantification Analysis on Potential Use of Recuperated Regenerative Braking Energy from NYCT Subways into Charging Electric Buses Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Engineering, Electrical Engineering At The City College of the City University of New York By Ahmed S. Rahman December 2018 Approved: Prof. Ahmed Mohamed, Thesis Advisor Department of Electrical Engineering Prof. Roger Dorsinville, Chairman Department of Electrical Engineering The City College of New York TOC-1 ABSTRACT The New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) is one of the biggest consumers of electricity in east coast of the United States. According to a report published by Dayton T. Brown in 2013, MTA consumes approximately 2150 GWh electrical energy per year for traction power, where the New York City Transit (NYCT) alone is a consumer of about 80% of the total annual MTA energy consumption.