And Paul on Jesus: a Comparative Study of Two Sacred Pillars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jihadism: Online Discourses and Representations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Studying Jihadism 2 3 4 5 6 Volume 2 7 8 9 10 11 Edited by Rüdiger Lohlker 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 The volumes of this series are peer-reviewed. 37 38 Editorial Board: Farhad Khosrokhavar (Paris), Hans Kippenberg 39 (Erfurt), Alex P. Schmid (Vienna), Roberto Tottoli (Naples) 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Rüdiger Lohlker (ed.) 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jihadism: Online Discourses and 8 9 Representations 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 With many figures 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 & 37 V R unipress 38 39 Vienna University Press 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; 24 detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

Inception and Ibn 'Arabi Oludamini Ogunnaike Harvard University, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 17 Article 10 Issue 2 October 2013 10-2-2013 Inception and Ibn 'Arabi Oludamini Ogunnaike Harvard University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Ogunnaike, Oludamini (2013) "Inception and Ibn 'Arabi," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol17/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Inception and Ibn 'Arabi Abstract Many philosophers, playwrights, artists, sages, and scholars throughout the ages have entertained and developed the concept of life being a "but a dream." Few works, however, have explored this topic with as much depth and subtlety as the 13thC Andalusian Muslim mystic, Ibn 'Arabi. Similarly, few works of art explore this theme as thoroughly and engagingly as Chistopher Nolan's 2010 film Inception. This paper presents the writings of Ibn 'Arabi and Nolan's film as a pair of mirrors, in which one can contemplate the other. As such, the present work is equally a commentary on the film based on Ibn 'Arabi's philosophy, and a commentary on Ibn 'Arabi's work based on the film. The ap per explores several points of philosophical significance shared by the film and the work of the Sufi as ge, and their relevance to contemporary conversations in philosophy, religion, and art. Keywords Ibn 'Arabi, Sufism, ma'rifah, world as a dream, metaphysics, Inception, dream within a dream, mysticism, Christopher Nolan Author Notes Oludamini Ogunnaike is a PhD candidate at Harvard University in the Dept. -

Transcendence of God

TRANSCENDENCE OF GOD A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE OLD TESTAMENT AND THE QUR’AN BY STEPHEN MYONGSU KIM A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (PhD) IN BIBLICAL AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: PROF. DJ HUMAN CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF. PGJ MEIRING JUNE 2009 © University of Pretoria DEDICATION To my love, Miae our children Yein, Stephen, and David and the Peacemakers around the world. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I thank God for the opportunity and privilege to study the subject of divinity. Without acknowledging God’s grace, this study would be futile. I would like to thank my family for their outstanding tolerance of my late studies which takes away our family time. Without their support and kind endurance, I could not have completed this prolonged task. I am grateful to the staffs of University of Pretoria who have provided all the essential process of official matter. Without their kind help, my studies would have been difficult. Many thanks go to my fellow teachers in the Nairobi International School of Theology. I thank David and Sarah O’Brien for their painstaking proofreading of my thesis. Furthermore, I appreciate Dr Wayne Johnson and Dr Paul Mumo for their suggestions in my early stage of thesis writing. I also thank my students with whom I discussed and developed many insights of God’s relationship with mankind during the Hebrew Exegesis lectures. I also remember my former teachers from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, especially from the OT Department who have shaped my academic stand and inspired to pursue the subject of this thesis. -

AL-GHAZĀLĪ AS an ISLAMIC REFORMER (MUSLIH): an Evaluative Study of the Attempts of the Imam Abū Hāmid Al-Ghazālī at Islamic Reform (Islāh)

AL-GHAZĀLĪ AS AN ISLAMIC REFORMER (MUSLIH): An Evaluative Study of the Attempts of the Imam Abū Hāmid al-Ghazālī at Islamic Reform (Islāh) by MOHAMED ABUBAKR A AL-MUSLEH A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology & Religion School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham July 2007 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Notwithstanding the enduring and rich “legacy of islāh (Islamic reform),” the study of it is relatively scarce and remarkably limited to the modern times. The present study attempts to shed some light on this legacy by evaluating the contribution of an outstanding pre-modern Muslim scholar, al-Ghazālī. Surprisingly, some studies create an absolutely positive picture of him, while others portray him in an extremely negative light. Thus, this study raises the question of whether it is justifiable to classify him as a muslih (Islamic reformer). In light of the analysis of the concept “islāh” and the complexity of al-Ghazālī’s time, the study demonstrates his life- experience and verifies that he devoted himself to general islāh at a late period of his life, after succeeding in his self-islāh. -

Naming God: a Quandary for Jews, Christians and Muslims

NAMING GOD: A QUANDARY FOR JEWS, CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS Spring McGinley Lecture, April 9-10, 2013 Patrick J. Ryan, S.J. Introduction: the Problem of Blasphemy Henri IV, the Huguenot King of Navarre, finally succeeded in taking the throne of France in 1590 after he renounced his Calvinist roots. Apt but unlikely legend has it that he said, at the time, that Paris vaut bien une messe (“Paris is well worth a mass.”) Despite his Calvinist upbringing and his subsequent conversion to Catholicism, Henri IV continued in bad habits: he kept mistresses and even made two of his illegitimate sons bishops, one at the age of six and the other at the age of four, and this despite the reforms introduced after the Council of Trent. Although many of the local clergy of Gallican sympathies disliked Henri IV, the French Jesuits did their best to deal with the reality of the only king they had, once he was established in Paris.1 The Jesuit Pierre Coton even served as the king’s confessor. One of the prevailing vices of Henri IV was a habit of blasphemy. Je renie Dieu, he would cry out in a moment of exasperation: “I renounce God.” In his typically Béarnais pronunciation, that exclamation by Henri IV would sound more like Jarnidieu. Hoping to help his penitent to renounce the evil habit of renouncing God on a regular basis, Père Coton suggested to Henri IV that he substitute for that blasphemy Je renie Coton, “I renounce Coton.” In the Béarnais dialect that came out as Jarnicoton, and the non-blasphemous curse word entered into the French language. -

Ninety-Nine Names of God in Islam

NINETY-NINE NAMES OF GOD IN ISLAM of portion of CHARLES STADE DAYSTAR PRESS P. 1261 l 1970 in mosaic tiles of Press, P. Box 1261, Ibadan, Nigeria PREFACE Every Muslim, as well as every student of is aware of fact that the bears constant witness to the absolute unity of God. This basic tenet finds its essential expression in Chapter 112 where one reads, "Say: He, God, is one. God is He on whom all depend. He not, nor is begotten, and none is like Him." However, the fact remains that basic essence and nature of this God is expressed in many different ways in the It is to that variety of expression that this study is addressed. The itself supplies the authority for this effort, since in four chapters it speaks of the "most beautiful names" of God. 970 The verses in question are: Copyright Robert Stade 1970 (A-2-8) "God there is no God but He. His are the most beautiful names." 17,110 (A-3-4): "Say: Call on God or call on the Merciful. By whatever name you call on Him, He has the most beautiful names." (A-3-19): "And God's are the most beautiful names, so call on Him thereby.. (B- 2): "He is God; the Creator, the the Fashioner. His are the most beautiful names." In respect of the verse numbering used above, the first is the number found in the Cairo text and the second as found in the (Western) text. This fact should be borne in mind by the reader as he endeavours to locate in his the various verses referred to in this study. -

Understanding Sufism

Abstract This thesis addresses the problem of how to interpret Islamic writers without imposing generic frameworks of later and partly Western derivation. It questions the overuse of the category “Sufism” which has sometimes been deployed to read anachronistic concerns into Islamic writers. It does so by a detailed study of some of the key works of the 13th century writer Ibn ‘Ata’ Allah (d. 709/1309). In this way it fills a gap in the learned literature in two ways. Firstly, it examines the legitimacy of prevalent conceptualisations of the category “Sufism.” Secondly, it examines the work of one Sufi thinker, and asks in what ways, if any, Western categories may tend to distort its Islamic characteristics. The methodology of the thesis is primarily exegetical, although significant attention is also paid to issues of context. The thesis is divided into two parts. Part One sets up the problem of Sufism as an organizational category in the literature. In doing so, this part introduces the works of Ibn ‘Ata’ Allah, and justifies the selection from his works for the case study in Part Two. Part Two provides a detailed case study of the works of Ibn ‘Ata’ Allah. It opens with some of the key issues involved in understanding an Islamic thinker, and gives a brief overview of Ibn ‘Ata’ Allah’s life. This is followed by an examination of materials on topics such as metaphysics, ontology, epistemology, eschatology, ethics, and soteriology. In each case it is suggested that these topics may be misleading unless care is taken not to import Western conceptuality where it is not justified by the texts. -

1849 Manuscript Info Abstract

ISSN 2320-5407 International Journal of Advanced Research (2016), Volume 4, Issue 7, 1849-1851 Journal homepage: http://www.journalijar.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL Journal DOI: 10.21474/IJAR01 OF ADVANCED RESEARCH RESEARCH ARTICLE The Rise of Islam. Dr. Zakera A. Siddiqui. I.C. Principal of F.D. Arts & Commerce College, Jamalpur, Ahmedabad. Manuscript Info Abstract Manuscript History: Received: 11 May 2016 Final Accepted: 22 June 2016 Published Online: July 2016 Key words: *Corresponding Author Dr. Zakera A. Siddiqui. Copy Right, IJAR, 2016,. All rights reserved. The universe, as we know is on the basis of cultures and traditions united by the knowledge and enlightenment of various books like Pavitra Quran-e-Sharif, The holy Bible, Bhagwad Gita etc. These oceans of knowledge not only teach us the way to oneness with God, but also demonstrate paths to lead a successful life in coordination with nature and divinity. This article provides information about one of the most precious and divine teachings known to humans, “Islam”. Islam is derived from the Arabic word "Salema": which means peace, purity, submission and obedience. In the religious sense, Islam means submission to the will of God and obedience to His law. Islam is a verbal noun 1849 ISSN 2320-5407 International Journal of Advanced Research (2016), Volume 4, Issue 7, 1849-1851 originating from the trilateral word s-l-m which forms a large class of words mostly relating to concepts of wholeness, submission, safeness and peace. In a religious context it means "voluntary submission to God". In Islam, God is beyond all comprehension and Muslims are not expected to visualize God. -

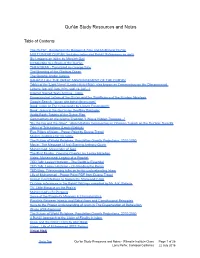

Qur'án Study Resources and Notes

Qur'án Study Resources and Notes Table of Contents The Qur'án: Renderings by Rodwell & Sale and Multilinear Qur'án MULTILINEAR QUR’ÁN (includes notes and Bahá’í References as well) Six Lessons on Islám by Marzieh Gail Introduction to a Study of the Qur'án: THE KORAN - Translated by George Sale The Meaning of the Glorious Quran The Quranic Arabic Corpus BAHA'U'LLAH: THE GREAT ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE QUR'AN Tablet of the 'Light Verse' (Lawh-i-Áyiy-i-Núr), also known as Commentary on the Disconnected Letters: (eg. alif, lam, mim, sad, ra, kaf,...) Internet Sacred Texts Archive - Islam Disconnected Letters of the Qur'an and the Significance of the Number Nineteen Google Search: “quran site:bahai-library.com” Book: Islam At The Crossroads by Lameh Fananapazir Book: Jesus in the Qur’an by Geoffrey Parrinder Audio Book: Tablets of the Divine Plan Commentary on the Islamic Tradition "I Was a Hidden Treasure..." "By the Fig and the Olive": `Abdu'l-Bahá's Commentary in Ottoman Turkish on the Qur'ánic Sura 95 Tablet of Tribulations (Lawḥ-i Baláyá) Five Pillars of Islam - Power Point by Duane Troxel Muslim guidance for life today The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050 Movie: The Message (3 hrs) Starring Anthony Quinn Muhammad: Messenger of God The First Muslim, Opening Chapter, by Lesley Hazelton Video: Muhammad: Legacy of a Prophet TED Talk: Lesley Hazleton - The Doubt is Essential TED Talk: Lesley Hazleton - On Reading the Koran TED Blog: 7 fascinating talks on better understanding Islam Life of Muhammad - Power Point PDF from Duane Troxel Islamic Contributions to Society by Stanwood Cobb Qur'ánic references in the Bahá'í Writings compiled by Mr. -

Jewish and Christian Religious Influences on Pre-Islamic Arabia on the Example of the Term RḤMNN ("The Merciful")

ORIENTALIA CHRISTIANA CRACOVIENSIA 3 (2011) Krzysztof Kościelniak Jagiellonian University in Krakow Jewish and Christian religious influences on pre-Islamic Arabia on the example of the term RḤMNN (“the Merciful”) The well known epithet, RḤMNN is constantly confirmed in inscriptions particularly from so-called “Late Sabaean Period” (after 380) which were associated with monotheism. In this time Judaism and Christianity attempted to replace the traditional South Arabian religion. In this context RḤMNN was used by polytheists Arabs, Jews and Christians. Raḥmānān’s connection to Arab Paganism Some authors argue that the epithet Raḥmān (“the Merciful”) has any connection to Arab Paganism – especially any connection to a lunar deity. They stress that Raḥmān is only Jewish-Christian origins and usage.1 It is the standard Muslim explanation, does not seem to be relevant for explanation of Raḥmānān’s historical connections with all Semitic world.2 The first know exampleRaḥmān ’ form (rḥmn) is bilingual inscription written in Akkadian and Aramaic which was found in the Tell Fekherye in northeast Syria. This inscription was dedicated to the Aramean god Hadad contenting following sentence: ‘lh. rḥmn zy. tṣlwth. ṭbh “merciful god to whom prayer is sweet.” In the Akkadian version Adad is called by the form rēmēnȗ. It is worth to add that rēmēnȗ was used as the epithet for god Marduk. Raḥmān in 1 Vgl. M. S. M. Saifullah, A. David, Raḥmānān (RḤMNN) – An Ancient South Arabian Moon God? in: http://www.islamic-awareness.org/Quran/Sources/Allah/rhmnn.html, quoted: 20.03.2011. 2 Vgl. A. Vargo, Responses to Islamic Awareness: Rahmanan (RHMNN) – An Ancient South Arabian Moon God?, in: http://www.answering-islam.org/Responses/Saifullah/rahman_av.htm, quoted: 10.04.2011. -

Naqshbandi Sufi, Persian Poet

ABD AL-RAHMAN JAMI: “NAQSHBANDI SUFI, PERSIAN POET A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Farah Fatima Golparvaran Shadchehr, M.A. The Ohio State University 2008 Approved by Professor Stephen Dale, Advisor Professor Dick Davis Professor Joseph Zeidan ____________________ Advisor Graduate Program in History Copyright by Farah Shadchehr 2008 ABSTRACT The era of the Timurids, the dynasty that ruled Transoxiana, Iran, and Afghanistan from 1370 to 1506 had a profound cultural and artistic impact on the history of Central Asia, the Ottoman Empire, and Mughal India in the early modern era. While Timurid fine art such as miniature painting has been extensively studied, the literary production of the era has not been fully explored. Abd al-Rahman Jami (817/1414- 898/1492), the most renowned poet of the Timurids, is among those Timurid poets who have not been methodically studied in Iran and the West. Although, Jami was recognized by his contemporaries as a major authority in several disciplines, such as science, philosophy, astronomy, music, art, and most important of all poetry, he has yet not been entirely acknowledged in the post Timurid era. This dissertation highlights the significant contribution of Jami, the great poet and Sufi thinker of the fifteenth century, who is regarded as the last great classical poet of Persian literature. It discusses his influence on Persian literature, his central role in the Naqshbandi Order, and his input in clarifying Ibn Arabi's thought. Jami spent most of his life in Herat, the main center for artistic ability and aptitude in the fifteenth century; the city where Jami grew up, studied, flourished and produced a variety of prose and poetry. -

A Brief Overview of Al Jinn Within Islamic Cosmology and Religiosity

Laughlin: A Brief Overview of al Jinn within Islamic Cosmology and Religios VIVIAN A. LAUGHLIN A Brief Overview of al Jinn within Islamic Cosmology and Religiosity Introduction For centuries humans have been fascinated and have had a deep at- traction for the supernatural, the unknown and the unseen. Whether it is with living creatures from other planets (i.e., visitors to this planet, chance meetings with the extra-terrestrial beings, sightings of unidenti- fied flying objects) or something as seemingly simple as speaking with psychics, reading one’s horoscope, or seeking someone to communicate with the dead. For some there is an unspoken fascination and/or longing for a deeper connection or insight into the cosmological plane within the spirit world. For others, spirits are no more than the souls of dead people, or ghosts, and even some pretend that spirits do not even exist. However, those who believe in a higher power know that spirits are either the forces of good or evil; both battling against each other to gain influence over hu- manity. Islamic religious beliefs tend to explain a realm of the unknown and unseen within cosmology. It is from this realm that Islam explains the world of al jinn and its connections to Islam. The Encyclopedia of the Qur’an defines cosmology as a “divinely gov- erned order of the universe and the place of humans within it” (Neuwirth 2001:441). This Qur’anic understanding of cosmology is taught within five very diverse sectors. These sectors are: (1) the divine six-day-work of cre- ation of the material world, (2) human kind and its habitat in nature, (3) demons or spirits (jinn), (4) the animal world, and (5) the resolution of created space on the day of doom (judgment).