Cinderelas Negras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Rainha Quelé: Raízes Do Empretecimento Do Samba1

A RAINHA QUELÉ: RAÍZES DO EMPRETECIMENTO DO SAMBA1 “Quelé” Queen: The Roots of the Samba Blackening Dmitri Cerboncini Fernandes* RESUMO Neste artigo analiso o advento de Clementina de Jesus ao cenáculo artístico na década de 1960. Seu surgimento possibilitou que certo nacionalismo de esquerda, até então propugnado de modo unívoco por um grupo de intelectuais e ativistas das artes populares, descobrisse uma nova feição, a que viria a ser considerada a mais “autêntica”: a afro-negro-brasileira. A partir deste ponto abria-se uma via aos movimentos negros e aos construtos que davam conta da categorização do outrora “nacional-universal” samba: o “verdadeiro” samba encontrava doravante a sua raiz exclusivamente afro-negra, ao passo que, de outro lado, o que se pode denominar imprecisa e vagamente de “cultura” afro-brasileira – ideário que em partes subsidiou a formação do Movimento Negro Unificado – o seu símbolo-mor nas artes nos anos 1970-80: o samba “verdadeiro”. Palavras-chave: Movimento Negro, Samba, Sociologia da Arte. ABSTRACT In this article I analyse the advent of Clementina de Jesus within the artistic cenacle of the 1960s. Her rise made possible that a certain left-wing nationalism, thus far advocated univocally by a group of intellectuals and activists from the popular arts, discovered a new feature, one that would come to be considered 1 Uma primeira versão deste artigo foi apresentada no 36.º Encontro anual da Anpocs, Grupo de Trabalho 30 – Relações Raciais: desigualdades, identidades e políticas públicas, em outubro de 2012. Agradeço as críticas e sugestões de Walter Risério. * Professor Adjunto II de Ciências Sociais na Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora. -

Mulheres Compositoras No Brasil Dos Séculos XIX E XX

REVISTA DO CENTRO DE PESQUISA E FORMAÇÃO / Nº 3, novembro 2016 Mulheres compositoras no Brasil dos séculos XIX e XX MULHERES Compositoras NO BrasiL dos SÉCULos XIX E XX Ana Carolina Arruda de Toledo Murgel1 Resumo O presente artigo traz os resultados parciais de minha pesquisa de pós-doutorado intitulada “Cartografias da Canção Feminina: composito- ras brasileiras do século XX”. O projeto, com apoio da FAPESP, visa le- vantar e analisar, numa perspectiva feminista, as obras de compositoras brasileiras no século XX (abarcando também as encontradas no século XIX), na tentativa de preencher uma lacuna frequentemente abordada na imprensa e em obras especializadas sobre a quase inexistência de mulhe- res na arte da composição musical, em especial até os anos de 1960. Palavras chave: Composição feminina. Música popular. Composito- ras brasileiras. ABstraCT This article presents the partial results of my post-doctoral research entitled “Cartography of Women Songs: Brazilian composers in the twen- tieth century”. The project, with support from FAPESP, intends to raise and analyze, from a feminist perspective, the works of Brazilian compo- sers in the twentieth century in an attempt to fill a gap often discussed in the press and specialized works on the near absence of women in the art of musical composition, particularly until the 1960s. Key words: Female composition. Popular music. Brazilian composers. Parece haver um consenso entre críticos musicais e a sociedade em geral de que as mulheres são excelentes intérpretes, mas que poucas se aventuraram na arte de compor. Em uma crítica escrita em 1996, no jor- nal Folha de S.Paulo, Pedro Sanches afirma: Com escassas exceções – Chiquinha Gonzaga, Dolores Duran, Maysa –, a composição no Brasil foi um ofício levado a cabo pelos homens até que a guerrilheira Rita Lee viesse cravar novos rumos. -

Música E Identidade De Marca: Uma Análise De Conteúdo Sobre a Atuação Da Marca Farm No Spotify

Faculdade de Comunicação Departamento de Audiovisuais e Publicidade Música e identidade de marca: uma análise de conteúdo sobre a atuação da marca Farm no Spotify Luana Gomes Gandra Coutinho Brasília 2019 Faculdade de Comunicação Departamento de Audiovisuais e Publicidade Luana Gomes Gandra Coutinho Música e identidade de marca: uma análise de conteúdo sobre a atuação da marca Farm no Spotify Projeto final em Publicidade e Propaganda apresentado à Faculdade de Comunicação da Universidade de Brasília, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do título de Bacharel em Comunicação Social, habilitação em Publicidade e Propaganda. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Elton Bruno Pinheiro Brasília 2019 Faculdade de Comunicação Departamento de Audiovisuais e Publicidade Luana Gomes Gandra Coutinho Projeto Final aprovado em ___/___/___ para obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Comunicação Social, habilitação Publicidade e Propaganda. BANCA EXAMINADORA ______________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Elton Bruno Pinheiro DAP/FAC/UnB | Orientador ______________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Edmundo Brandão Dantas DAP/FAC/UnB | Examinador ______________________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Suelen Brandes Marques Valente DAP/FAC/UnB | Examinadora ______________________________________________________ Prof. Me. Mauro Celso Maia FAC/UnB | Suplente Brasília 2019 Tudo o que uma marca faz pode ser entendido como um capítulo da sua história, contada com o objetivo de reforçar o seu significado e, como consequência, envolver os que se identificam com tais narrativas. (Ronaldo Fraga). Agradecimentos Aos meus pais, a minha família e amigos, pelo apoio, pelo suporte e pela companhia nessa caminhada. A Suelen, Edmundo e Mauro, por aceitarem compor a banca e participar desse projeto muito especial para mim. A Rafa e Clara por compartilharem comigo essa experiência e terem feito dela mais feliz e prazerosa. -

1 -A Análise Sociológica De Letras De Música

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SOCIOLOGIA A Análise Social nas Letras das Canções de Lupicínio Rodrigues Daniel de Almeida Pinto Kirjner Professora Doutora Maria Angélica Brasil Gonçalves Madeira Orientadora Banca: Prof. Doutor Marcelo Carvalho Rosa (UnB) Banca:Maria Therezinha Ferraz Negrão de Mello (UnB) Brasília Março de 2011 1 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SOCIOLOGIA A Análise Social nas Letras das Canções de Lupicínio Rodrigues Daniel de Almeida Pinto Kirjner Dissertação apresentada ao Departamento de Sociologia da Universidade de Brasília/UnB como parte dos requisitos para a obtenção do título de mestre. Brasília Março de 2011 2 Sumário I – Agradecimentos...............................................................................................................................4 II - Introdução ......................................................................................................................................5 1 - A Análise Sociológica de Letras de Música....................................................................................8 1.1 - Samba-canção: Fratura e Paixão.........................................................................................9 1.2 – Lupicínio Rodrigues: o Feminino, o Masculino e Suas Relações. .................................15 1.3 – Contribuições de Teorias da Ação...................................................................................30 1.3.1 – A Agência -

Apontamentos Para Uma Crítica Musical

VANGUARDA PAULISTA: APONTAMENTOS PARA UMA CRÍTICA MUSICAL José Adriano Fenerick * Universidade de São Paulo – USP [email protected] RESUMO : Este artigo é um estudo sobre a crítica cultural (musical) contida nas canções da chamada Vanguarda Paulista. Inseridos no campo dos alternativos e independentes do começo da década de 1980, e portanto distantes das regras impostas pelo grande mercado de música no país, os integrantes da Vanguarda Paulista criaram um contraponto crítico e importante, registrado em suas canções, para se pensar a produção musical brasileira disseminada pela indústria cultural nos últimos 20 anos. Assim, ao analisar algumas de suas canções, este estudo procura pontuar e debater alguns aspectos da cultura musical brasileira recente. ABSTRACT: This article is a study about the cultural critic (musical) contained in the songs of the Vanguarda Paulista. Inserted in the field of the underground and countercultural of the 1980’s, and therefore distant of the imposed rules by the big music market in the country, the members of the Vanguarda Paulista created a critical and important counterpoint, registered in their songs, to think the Brazilian musical production disseminated by the cultural industry in the last 20 years. Like this, upon analysis of some songs, this study tries to punctuate and to debate some aspects of the actual Brazilian musical culture. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Vanguarda Paulista – Indústria Cultural – Música Popular Brasileira KEYWORDS: Vanguarda Paulista – Cultural Industry – Brazilian Popular Music Em um de seus ensaios T. W. Adorno diz o seguinte: “o crítico da cultura não está satisfeito com a cultura, mas deve unicamente a ela esse seu mal estar”. -

O Uso Do Tamborim Por Mestre Marçal: Legado E Estudo Interpretativo

VINÍCIUS DE CAMARGO BARROS O USO DO TAMBORIM POR MESTRE MARÇAL: LEGADO E ESTUDO INTERPRETATIVO CAMPINAS 2015 i ii UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS Instituto de Artes VINÍCIUS DE CAMARGO BARROS O USO DO TAMBORIM POR MESTRE MARÇAL: LEGADO E ESTUDO INTERPRETATIVO Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada a Pós-Graduação do Instituto de Artes da Universidade Estadual de Campinas como parte dos requisitos exigidos para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música. Área de concentração: Música: Teoria, Criação e Prática. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Fernando Augusto de Almeida Hashimoto ESTE EXEMPLAR CORRESPONDE À VERSÃO FINAL DA DISSERTAÇÃO DEFENDIDA PELO ALUNO VINÍCIUS DE CAMARGO BARROS, E ORIENTADO PELO PROF. DR. FERNANDO AUGUSTO DE ALMEIDA HASHIMOTO. ASSINATURA DO ORIENTADOR ______________________________ CAMPINAS 2015 iii iv v Para Léia, Guilherme e Fernando com carinho. vi Agradecimentos Aos meus pais, Márcio e Marite, e meus irmãos, Murilo e Felipe, pelo apoio irrestrito sempre. Ao orientador Prof. Dr. Fernando Hashimoto pela confiança e pelas preciosas intervenções. Aos professores que integraram as bancas de qualificação, recital e defesa do mestrado, José Alexandre Carvalho, Budi Garcia, Leandro Barsalini e Carlos Stasi. A família Marçal (Armando e Niltinho). Aos amigos Rodrigo Morte, Guilherme Marques, Guca Domenico, Rodrigo Marinonio, Leandro Lui, Rogério Boccato, Deni Domenico, Nelton Essi, Rodolfo Arilho, Osvaldo Bigaram, Vana Gierig, Antonio de Almeida (Toniquinho) e Glaúcia Vidal que estiveram presentes desde o principio do me ajudando com o projeto. Aos meus professores Rui Carvalho (meu primeiro incentivador), Eduardo Gianesella, Luis Caldana, Luiz Guello (pela sugestão do tema), John Boudler, Carlos Stasi, Alberto Ikeda e Gersinho da Banda. A todos que gentilmente, sem medir esforços se dispuseram a participar com inúmeras contribuições, Barão do Pandeiro, Beto Cazes, Oscar Bolão, Paulinho Bicolor, Vitor Pessoa, Sérgio Barba, Danilo Moura, Teco Martins, Lua Lafaiette, Hélio Cunha. -

O Imaginêrio De Antonio Carlos Jobim

O IMAGINÁRIO DE ANTONIO CARLOS JOBIM: REPRESENTAÇÕES E DISCURSOS Patrícia Helena Fuentes Lima A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages (Portuguese). Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Advisor: Monica Rector Reader: Teresa Chapa Reader: John Chasteen Reader: Fred Clark Reader: Richard Vernon © 2008 Patrícia Helena Fuentes Lima ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT PATRÍCIA HELENA FUENTES LIMA: Antonio Carlos Jobim: representações e discursos (Under the direction of Monica Rector) My aim with the present work is to describe the personal and creative trajectory of this artist that became known to his audience and people as a hero in the mythological sense—an individual that constructs a series of victories and defeats that continues until death, after which he is glorified by his community. Therefore, I approach the narratives that made him famous: the ones produced by the print press as well as those texts that negotiate meaning, memory, domain and identity created by his fans. I will place special emphasis on the fact that his public produced a definitive narrative about his figure, an account imbued with devotion, familiarity and creativity following his death. More specifically, I identify intertwined relations between the Brazilian audience and the media involved with creating the image of Antonio Carlos Jobim. My hypothesis is that Antonio Carlos Jobim’s image was exhaustively associated with the Brazilian musical movement Bossa Nova for ideological reasons. Specially, during a particular moment in Brazilian history—the Juscelino Kubitschek’s years (1955-1961). -

Batuqueiros Da Paulicéia”, Com 4 Shows Na Chopperia Do Sesc-Pompéia

Osvaldinho da Cuíca lança o livro “Batuqueiros da Paulicéia”, com 4 shows na Chopperia do Sesc-Pompéia Com mais de 50 anos de carreira, músico se apresenta de 7 a 10 de maio e recebe convidados especiais para mostrar a qualidade do Samba de São Paulo. Uma frase infeliz de Vinícius de Moraes, a famosa “São Paulo é o túmulo do samba!”, fez cristalizar-se um antigo preconceito contra o samba paulista. Os trabalhos de grandes sambistas de São Paulo, como Henricão, Geraldo Filme, Adoniran Barbosa e Toquinho (o mais prolífico parceiro do poeta), sempre foram lembrados como casos que desmentiam tal injustiça, mas uma defesa do samba de São Paulo, como um todo, dificilmente passou de um esboço. Até porque, em boa medida, os próprios paulistas não conhecem bem a sua grandeza. Daí o impulso do sambista Osvaldinho da Cuíca e do crítico e pesquisador André Domingues se unirem para sistematizar e escrever a história do samba paulista no livro Batuqueiros da Paulicéia – Enredos do Samba de São Paulo (Editora Barcarolla), que será lançado com uma série de quatro shows na Chopperia do Sesc-Pompéia, entre os dias 7 e 10 de maio. A obra segue as diversas trilhas do samba de São Paulo, apontando seus nomes e acontecimentos fundamentais desde o início do século XX até o presente, do remoto samba- rural ao “samba-de-raiz” de hoje em dia, passando, ainda, por diversas manifestações como a marcha-sambada, a batucada de engraxates, o samba-rock e as experiências da chamada Vanguarda Paulistana. Nos shows de lançamento, o mestre Osvaldinho mostrará o repertório descrito em Batuqueiros da Paulicéia , relembrando músicas de antigos carnavais paulistanos, sambas de rua, sambas-rurais e sucessos de sambistas importantes da nossa história, como Henricão, Geraldo Filme, Adoniran Barbosa e ele próprio, um artífice muito privilegiado dessa história, com seus 51 anos de carreira. -

O Homoerotismo Em Canções Interpretadas Por Cássia Eller: Psicologia, Literatura E Semiótica

O HOMOEROTISMO EM CANÇÕES INTERPRETADAS POR CÁSSIA ELLER: PSICOLOGIA, LITERATURA E SEMIÓTICA Ertz Clarck Melindre dos Santos* (Técnico em Assuntos Educacionais do Departamento de Antropologia e Museologia/UFPE-Campus Recife, Licenciado Pleno em Letras/UNIFAP, Psicólogo/UFMS-Campus do Pantanal, Designer de Moda/Faculdade SENAC-PE, Especialista em Literatura Brasileira/PUC Minas, Mestre em Psicologia Clínica/UNICAP e Doutorando em Psicologia/UNESP-Campus de Assis, Recife/PE – Brasil); Fernando Silva Teixeira Filho (Mestre e Doutor em Psicologia Clínica/PUC-São Paulo, Professor Adjunto e Livre Docente em Psicologia Clínica no Departamento de Psicologia Clínica da UNESP, Campus de Assis – Brasil). contato: [email protected] Palavras-chave: Homossexualidades. Música popular brasileira. Interpretações. O HOMOEROTISMO EM CANÇÕES INTERPRETADAS POR CÁSSIA ELLER: PSICOLOGIA, LITERATURA E SEMIÓTICA. 1. Introdução A música popular brasileira é uma expressão artística de notória riqueza em se tratando de cantores, estilos e ritmos. Para Tatit (1995, p. 11) “o compositor traz sempre um projeto geral de dicção que será aprimorado ou modificado pelo cantor e, normalmente modalizado pelo arranjador. Todos são, nesse sentido cancionistas”. Baseando-nos na visão integralizante acima mencionada podemos considerar cancionistas personalidades como Caetano Veloso, Chico Buarque, Cazuza, Gilberto Gil, Hermelino Neder, Arrigo Barnabé, Luiz Pinheiro, Riachão, Ataulfo Alves e Itamar Assumpção. O estudo dessa futura pesquisa será acerca de uma outra cancionista que interpretou todos esses profissionais da MPB anteriormente elencados: Cássia Rejane Eller, ou melhor, Cássia Eller. Em 1962, ano de seu nascimento, o mundo passava a conhecer a Bossa Nova, pois algumas canções da época como “Samba de uma nota só” (Tom Jobim) e “O barquinho” (Roberto Menescal) foram apresentadas no Carnegie Hall, em Nova York. -

Rádio Nacional Fm De Brasília

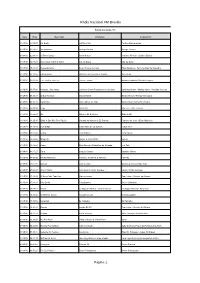

Rádio Nacional FM Brasília RÁDIO NACIONAL FM Data Hora Descrição Intérprete Compositor 01/09/16 00:02:27 For Emily Luiz Eça Trio Pacífico Mascarenhas 01/09/16 01:56:02 Ser Brasileiro George Durand George Durand 01/09/16 02:54:31 A Última Dança Paula Nunes Vanessa Pinheiro / Lidiana Enéias 01/09/16 04:01:21 Uma Gaita Sobre O Morro Edu da Gaita Edu da Gaita 01/09/16 05:00:26 Pressentimento Grupo Toque de Salto Elton Medeiros / Hermínio Belo de Carvalho 01/09/16 06:00:56 Fita Amarela Martinho da Vila & Aline Calixto Noel Rosa 01/09/16 06:03:38 Tim Tim Por Tim Tim Leonel Laterza Haroldo Barbosa / Geraldo Jaques 01/09/16 06:07:43 Verdade, Uma Ilusão Carlinhos Brown/Paralamas do Sucesso Carlinhos Brown / Marisa Monte / Arnaldo Antunes 01/09/16 06:11:31 O Que Se Quer Marisa Monte Marisa Monte / Rodrigo Amarante 01/09/16 06:14:12 Geraldofla Mário Adnet & Lobão Mário Adnet / Bernardo Vilhena 01/09/16 06:18:14 Pagu Maria Rita Rita Lee / Zélia Duncan 01/09/16 06:22:27 Ela Gilberto Gil & Moska Gilberto Gil 01/09/16 06:25:16 Onde A Dor Não Tem Razão Mariana de Moraes & Zé Renato Paulinho da Viola / Elton Medeiros 01/09/16 06:29:06 Dois Cafés Tulipa Ruiz & Lulu Santos Tulipa Ruiz 01/09/16 06:32:46 Lenha Zeca Baleiro Zeca Baleiro 01/09/16 06:36:42 Milagreiro Djavan & Cássia Eller Djavan 01/09/16 06:42:26 Capitu Zélia Duncan & Hamilton de Holanda Luiz Tatit 01/09/16 06:47:27 Terra Caetano Veloso Caetano Veloso 01/09/16 06:53:55 Pavão Misterioso Ednardo, Amelinha & Belchior Ednardo 01/09/16 06:57:56 Estrelar Marcos Valle Marcos & Paulo Sérgio Valle 01/09/16 -

Black Music of All Colors

SÉRIE ANTROPOLOGIA 145 BLACK MUSIC OF ALL COLORS. THE CONSTRUCTION OF BLACK ETHNICITY IN RITUAL AND POPULAR GENRES OF AFRO-BRAZILIAN MUSIC José Jorge de Carvalho Brasília 1993 Black Music of all colors. The construction of Black ethnicity in ritual and popular genres of Afro-Brazilian Music. José Jorge de Carvalho University of Brasília The aim of this essay is to present an overview of the charter of Afro-Brazilian identities, emphasizing their correlations with the main Afro-derived musical styles practised today in the country. Given the general scope of the work, I have chosen to sum up this complex mass of data in a few historical models. I am interested, above all, in establishing a contrast between the traditional models of identity of the Brazilian Black population and their musics with recent attempts, carried out by the various Black Movements, and expressed by popular, commercial musicians who formulate protests against that historical condition of poverty and unjustice, forging a new image of Afro- Brazilians, more explicit, both in political and in ideological terms. To focus such a vast ethnographic issue, I shall analyse the way these competing models of identity are shaped by the different song genres and singing styles used by Afro-Brazilians running through four centuries of social and cultural experience. In this connection, this study is also an attempt to explore theoretically the more abstract problems of understanding the efficacy of songs; in other words, how in mythopoetics, meaning and content are revealed in aesthetic symbolic structures which are able to mingle so powerfully verbal with non-verbal modes of communication. -

PEQUENA HISTÓRIA DO CARNAVAL CARIOCA De Suas Origens Aos Dias Atuais José Luiz De Oliveira 1

ENCONTROS – ANO 10 – Número 18 – 1º semestre 2012 PEQUENA HISTÓRIA DO CARNAVAL CARIOCA De suas origens aos dias atuais José Luiz de Oliveira 1 Resumo: O artigo empreende, em linhas gerais, uma análise do Carnaval na cidade do Rio de Janeiro, suas criações e letras de samba a partir dos vínculos entre história, política e cultura, e assim revisita desde as suas origens até as Escolas de Samba, cujas representações expressavam a busca do consenso e a defesa da ordem interna no contexto da ditadura militar. Palavras-chave: Carnaval; Escolas de Samba; consenso; ordem interna; ditadura militar. Abstract: The article aims at making in general terms an analysis of Carnival in city of Rio de Janeiro such as its creations and samba lyrics from the bonds linking history, politics and culture. In doing so, it revisits from its origins to the Samba Schools, which representations have expressed the search of consensus as well as the defense of internal order in the historical context of the military dictatorship. Keywords: Carnival; Samba School; consensus; internal order; military dictatorship. I – Introdução: O que leva um historiador que não é carnavalesco a se interessar, pesquisar e escrever sobre carnaval? Prova maior deste questionamento encontra-se no fato de que durante os famosos “Folguedos de Momo”, em 2012, praticamente me exilei em Teresópolis em um retiro quase que franciscano longe da grande festa que acontecia a poucos quilômetros na cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Procurarei responder a esta e outras indagações ao longo deste artigo que tem por objetivo fazer uma reflexão de uma das marcas da sociedade brasileira, o carnaval.