The Gut Microbiota of Colombians Differs from That of Americans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fatty Acid Diets: Regulation of Gut Microbiota Composition and Obesity and Its Related Metabolic Dysbiosis

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Fatty Acid Diets: Regulation of Gut Microbiota Composition and Obesity and Its Related Metabolic Dysbiosis David Johane Machate 1, Priscila Silva Figueiredo 2 , Gabriela Marcelino 2 , Rita de Cássia Avellaneda Guimarães 2,*, Priscila Aiko Hiane 2 , Danielle Bogo 2, Verônica Assalin Zorgetto Pinheiro 2, Lincoln Carlos Silva de Oliveira 3 and Arnildo Pott 1 1 Graduate Program in Biotechnology and Biodiversity in the Central-West Region of Brazil, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; [email protected] (D.J.M.); [email protected] (A.P.) 2 Graduate Program in Health and Development in the Central-West Region of Brazil, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; pri.fi[email protected] (P.S.F.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (P.A.H.); [email protected] (D.B.); [email protected] (V.A.Z.P.) 3 Chemistry Institute, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-67-3345-7416 Received: 9 March 2020; Accepted: 27 March 2020; Published: 8 June 2020 Abstract: Long-term high-fat dietary intake plays a crucial role in the composition of gut microbiota in animal models and human subjects, which affect directly short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production and host health. This review aims to highlight the interplay of fatty acid (FA) intake and gut microbiota composition and its interaction with hosts in health promotion and obesity prevention and its related metabolic dysbiosis. -

Effect of Vertical Flow Exchange on Microbial Community Dis- Tributions in Hyporheic Zones

Article 1 by Heejung Kim and Kang-Kun Lee* Effect of vertical flow exchange on microbial community dis- tributions in hyporheic zones School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Republic of Korea; *Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] (Received: November 2, 2018; Revised accepted: January 6, 2019) https://doi.org/10.18814/epiiugs/2019/019001 The effect of the vertical flow direction of hyporheic flux advance of hydrodynamic modeling has improved research of hydro- on the bacterial community is examined. Vertical velocity logical exchange processes at the hyporheic zone (Cardenas and Wil- change of the hyporheic zone was examined by installing son, 2007; Fleckenstein et al., 2010; Endreny et al., 2011). Also, this a piezometer on the site, and a total of 20,242 reads were zone has plentiful micro-organisms. The hyporheic zone constituents analyzed using a pyrosequencing assay to investigate the a dynamic hotspot (ecotone) where groundwater and surface water diversity of bacterial communities. Proteobacteria (55.1%) mix (Smith et al., 2008). were dominant in the hyporheic zone, and Bacteroidetes This area constitutes a flow path along which surface water down wells into the streambed sediment and groundwater up wells in the (16.5%), Actinobacteria (7.1%) and other bacteria phylum stream, travels for some distance before eventually mixing with (Firmicutes, Cyanobacteria, Chloroflexi, Planctomycetesm groundwater returns to the stream channel (Hassan et al., 2015). Sur- and unclassified phylum OD1) were identified. Also, the face water enters the hyporheic zone when the vertical hydraulic head hyporheic zone was divided into 3 points – down welling of surface water is greater than the groundwater (down welling). -

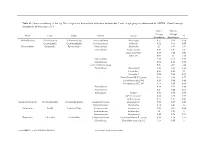

Genus Contributing to the Top 70% of Significant Dissimilarity of Bacteria Between Day 7 and 18 Age Groups As Determined by SIMPER

Table S1: Genus contributing to the top 70% of significant dissimilarity of bacteria between day 7 and 18 age groups as determined by SIMPER. Overall average dissimilarity between ages is 51%. Day 7 Day 18 Average Average Phyla Class Order Family Genus % Abundance Abundance Actinobacteria Actinobacteria Actinomycetales Actinomycetaceae Actinomyces 0.57 0.24 0.74 Coriobacteriia Coriobacteriales Coriobacteriaceae Collinsella 0.51 0.61 0.57 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides 2.1 1.63 1.03 Marinifilaceae Butyricimonas 0.82 0.81 0.9 Sanguibacteroides 0.08 0.42 0.59 CAG-873 0.01 1.1 1.68 Marinifilaceae 0.38 0.78 0.91 Marinifilaceae 0.78 1.04 0.97 p-2534-18B5 gut group 0.06 0.7 1.04 Prevotellaceae Alloprevotella 0.46 0.83 0.89 Prevotella 2 0.95 1.11 1.3 Prevotella 7 0.22 0.42 0.56 Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group 0.62 0.68 0.77 Prevotellaceae UCG-003 0.26 0.64 0.89 Prevotellaceae UCG-004 0.11 0.48 0.68 Prevotellaceae 0.64 0.52 0.89 Prevotellaceae 0.27 0.42 0.55 Rikenellaceae Alistipes 0.39 0.62 0.77 dgA-11 gut group 0.04 0.38 0.56 RC9 gut group 0.79 1.17 0.95 Epsilonbacteraeota Campylobacteria Campylobacterales Campylobacteraceae Campylobacter 0.58 0.83 0.97 Helicobacteraceae Helicobacter 0.12 0.41 0.6 Firmicutes Bacilli Lactobacillales Enterococcaceae Enterococcus 0.36 0.31 0.64 Lactobacillaceae Lactobacillus 1.4 1.24 1 Streptococcaceae Streptococcus 0.82 0.58 0.53 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Christensenellaceae Christensenellaceae R-7 group 0.38 1.36 1.56 Clostridiaceae Clostridium sensu stricto 1 1.16 0.58 -

Exploring Salivary Microbiota in AIDS Patients with Different Periodontal Statuses Using 454 GS-FLX Titanium Pyrosequencing

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 02 July 2015 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00055 Exploring salivary microbiota in AIDS patients with different periodontal statuses using 454 GS-FLX Titanium pyrosequencing Fang Zhang 1 †, Shenghua He 2 †, Jieqi Jin 1, Guangyan Dong 1 and Hongkun Wu 3* 1 State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, West China College of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China, 2 Public Health Clinical Center of Chengdu, Chengdu, China, 3 Department of Geriatric Dentistry, West China College of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China Patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) are at high risk of opportunistic infections. Oral manifestations have been associated with the level of immunosuppression, these include periodontal diseases, and understanding the microbial populations in the oral cavity is crucial for clinical management. The aim of this study was to examine the salivary bacterial diversity in patients newly admitted to the AIDS ward of the Public Health Clinical Center (China). Saliva samples were Edited by: Saleh A. Naser, collected from 15 patients with AIDS who were randomly recruited between December University of Central Florida, USA 2013 and March 2014. Extracted DNA was used as template to amplify bacterial Reviewed by: 16S rRNA. Sequencing of the amplicon library was performed using a 454 GS-FLX J. Christopher Fenno, University of Michigan, USA Titanium sequencing platform. Reads were optimized and clustered into operational Nick Stephen Jakubovics, taxonomic units for further analysis. A total of 10 bacterial phyla (106 genera) were Newcastle University, UK detected. Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria were preponderant in the *Correspondence: salivary microbiota in AIDS patients. The pathogen, Capnocytophaga sp., and others Hongkun Wu, Department of Geriatric Dentistry, not considered pathogenic such as Neisseria elongata, Streptococcus mitis, and West China College of Stomatology, Mycoplasma salivarium but which may be opportunistic infective agents were detected. -

1 1 Children Developing Celiac Disease Have a Distinct And

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.29.971242; this version posted March 3, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 2 Children Developing Celiac Disease Have a Distinct and Proinflammatory Gut 3 Microbiota in the First 5 Years of Life 4 5 Qian Huang1, Yi Yang2, Vladimir Tolstikov3, Michael A. Kiebish3, Jonas F 6 Ludvigsson4,5, Noah W. Palm2, Johnny Ludvigsson6, Emrah Altindis1 7 8 9 Affiliations: 10 1 Boston College Biology Department, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467, USA 11 2 Department of Immunobiology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 12 06510, USA. 13 14 3 BERG, LLC, Framingham, MA, USA. 15 16 4 Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, 17 Stockholm, Sweden 18 19 5 Department of Paediatrics, Örebro University Hospital, Sweden 20 6 Crown Princess Victoria's Children's Hospital, Region Östergötland, Division of 21 Pediatrics, Linköping University, Linköping, SE 58185, Sweden. 22 23 24 25 26 27 Correspondence to: Emrah Altindis, Boston College Biology Department, Higgins Hall, 28 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill, MA 02467. E-mail: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.29.971242; this version posted March 3, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 29 ABSTRACT 30 Objective: Celiac disease (CD) is an immune-mediated disease characterized by small intestinal 31 inflammation. -

Effect of Dietary Fat on the Metabolism of Energy and Nitrogen, Serum

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/438929; this version posted October 9, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Effect of Dietary Fat on the Metabolism of Energy and 2 Nitrogen, Serum Parameters, Rumen Fermentation, 3 and Microbiota in twin Hu Male Lambs 4 Wenjuan Lia, Hui Taoa, Naifeng Zhanga, Tao Maa, Kaidong Dengb, Biao Xiea, Peng Jiaa, Qiyu 5 Diaoa* 6 aFeed Research Institute, Key Laboratory of Feed Biotechnology of the Ministry of 7 Agriculture, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100081, China 8 bCollege of Animal Science, Jinling Institute of Technology, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China 9 *Corresponding author 10 E-mail:[email protected] 11 Abstract 12 Background: Fat is the main substance that provides energy to animals. However, 13 the use of fat in twin Hu lambs has not been investigated. Thirty pairs of male twin 14 lambs were examined to investigate the effects of dietary fat on the metabolism of 15 energy and nitrogen, ruminal fermentation, and microbial communities. The twins are 16 randomly allotted to two groups (high fat: HF, normal fat: NF). Two diets of equal 17 protein and different fat levels. The metabolism test was made at 50-60 days of age. 18 Nine pairs of twin lambs are slaughtered randomly, and the rumen fluid is collected at 19 60 days of age. 20 Results: The initial body weight (BW) in the HF group did not differ from that of NF 21 group (P > 0.05), but the final BW was tended to higher than that of NF group (0.05 < 22 P < 0.1). -

Fecal Microbiota Alterations and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Functional Abdominal Bloating/Distention

J Neurogastroenterol Motil, Vol. 26 No. 4 October, 2020 pISSN: 2093-0879 eISSN: 2093-0887 https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm20080 JNM Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility Original Article Fecal Microbiota Alterations and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Functional Abdominal Bloating/Distention Choong-Kyun Noh and Kwang Jae Lee* Department of Gastroenterology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Gyeonggi-do, Korea Background/Aims The pathophysiology of functional abdominal bloating and distention (FABD) is unclear yet. Our aim is to compare the diversity and composition of fecal microbiota in patients with FABD and healthy individuals, and to evaluate the relationship between small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and dysbiosis. Methods The microbiota of fecal samples was analyzed from 33 subjects, including 12 healthy controls and 21 patients with FABD diagnosed by the Rome IV criteria. FABD patients underwent a hydrogen breath test. Fecal microbiota composition was determined by 16S ribosomal RNA amplification and sequencing. Results Overall fecal microbiota composition of the FABD group differed from that of the control group. Microbial diversity was significantly lower in the FABD group than in the control group. Significantly higher proportion of Proteobacteria and significantly lower proportion of Actinobacteria were observed in FABD patients, compared with healthy controls. Compared with healthy controls, significantly higher proportion of Faecalibacterium in FABD patients and significantly higher proportion of Prevotella and Faecalibacterium in SIBO (+) patients with FABD were found. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, was significantly more abundant, but Bacteroides uniformis and Bifidobacterium adolescentis were significantly less abundant in patients with FABD, compared with healthy controls. Significantly more abundant Prevotella copri and F. -

Bacterial Diversity and Functional Analysis of Severe Early Childhood

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Bacterial diversity and functional analysis of severe early childhood caries and recurrence in India Balakrishnan Kalpana1,3, Puniethaa Prabhu3, Ashaq Hussain Bhat3, Arunsaikiran Senthilkumar3, Raj Pranap Arun1, Sharath Asokan4, Sachin S. Gunthe2 & Rama S. Verma1,5* Dental caries is the most prevalent oral disease afecting nearly 70% of children in India and elsewhere. Micro-ecological niche based acidifcation due to dysbiosis in oral microbiome are crucial for caries onset and progression. Here we report the tooth bacteriome diversity compared in Indian children with caries free (CF), severe early childhood caries (SC) and recurrent caries (RC). High quality V3–V4 amplicon sequencing revealed that SC exhibited high bacterial diversity with unique combination and interrelationship. Gracillibacteria_GN02 and TM7 were unique in CF and SC respectively, while Bacteroidetes, Fusobacteria were signifcantly high in RC. Interestingly, we found Streptococcus oralis subsp. tigurinus clade 071 in all groups with signifcant abundance in SC and RC. Positive correlation between low and high abundant bacteria as well as with TCS, PTS and ABC transporters were seen from co-occurrence network analysis. This could lead to persistence of SC niche resulting in RC. Comparative in vitro assessment of bioflm formation showed that the standard culture of S. oralis and its phylogenetically similar clinical isolates showed profound bioflm formation and augmented the growth and enhanced bioflm formation in S. mutans in both dual and multispecies cultures. Interaction among more than 700 species of microbiota under diferent micro-ecological niches of the human oral cavity1,2 acts as a primary defense against various pathogens. Tis has been observed to play a signifcant role in child’s oral and general health. -

Analysis of the Gut Bacterial Communities in Beef Cattle and Their Association with Feed Intake, Growth, and Efficiency1,2,3

Published online July 13, 2017 Analysis of the gut bacterial communities in beef cattle and their association with feed intake, growth, and efficiency1,2,3 P. R. Myer,*4 H. C. Freetly,† J. E. Wells,† T. P. L. Smith,† and L. A. Kuehn† *Department of Animal Science, University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture, University of Tennessee, Knoxville 37996; and †USDA5, ARS, U.S. Meat Animal Research Center, Clay Center, NE 68933 ABSTRACT: The impetus behind the global food secu- utilization. The use of metagenomics and high-through- rity challenge is direct, with the necessity to feed almost put sequencing has greatly impacted the study of the 10 billion people by 2050. Developing a food-secure ruminant gut. The ability to interrogate these systems at world, where people have access to a safe and sustain- great depth has permitted a greater understanding of the able food supply, is the principal goal of this challenge. microbiological and molecular mechanisms involved To achieve this end, beef production enterprises must in ruminant nutrition and health. Although the micro- develop methods to produce more pounds of animal bial communities of the reticulorumen have been well protein with less. Selection for feed-efficient beef cattle documented to date, our understanding of the popu- using genetic improvement technologies has helped to lations within the gastrointestinal tract as a whole is understand and improve the stayability and longevity limited. The composition and phylogenetic diversity of of such traits within the herd. Yet genetic contributions the gut microbial community are critical to the overall to feed efficiency have been difficult to identify, and well-being of the host and must be determined to fully differing genetics, feed regimens, and environments understand the relationship between the microbiomes among studies contribute to great variation and inter- within segments of the cattle gastrointestinal tract and pretation of results. -

Bacteriophages As Potential New Mammalian Pathogens George V

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Bacteriophages as potential new mammalian pathogens George V. Tetz 1, Kelly V. Ruggles2,3, Hua Zhou3, Adriana Heguy4,5,6, Aristotelis Tsirigos3,4,5 & Victor Tetz1 Received: 4 May 2017 Increased intestinal permeability and translocation of gut bacteria trigger various polyaetiological Accepted: 23 June 2017 diseases associated with chronic infammation and underlie a variety of poorly treatable pathologies. Published online: 1 August 2017 Previous studies have established a primary role of the microbiota composition and intestinal permeability in such pathologies. Using a rat model, we examined the efects of exposure to a bacteriophage cocktail on intestinal permeability and relative abundance of taxonomic units in the gut bacterial community. There was an increase in markers of impaired gut permeability, such as the lactulose/mannitol ratio, plasma endotoxin concentrations, and serum levels of infammation- related cytokines, following the bacteriophage challenge. We observed signifcant diferences in the alpha diversity of faecal bacterial species and found that richness and diversity index values increased following the bacteriophage challenge. There was a reduction in the abundance of Blautia, Catenibacterium, Lactobacillus, and Faecalibacterium species and an increase in Butyrivibrio, Oscillospira and Ruminococcus after bacteriophage administration. These fndings provide novel insights into the role of bacteriophages as potentially pathogenic for mammals and their possible implication in the development of diseases associated with increased intestinal permeability. Our knowledge of the intestinal microbiota has greatly expanded over the last decade, and growing evidence sug- gests that alterations of the intestinal microbiota are critical pathogenic factors that trigger various polyaetiologi- cal diseases associated with increased intestinal permeability and chronic infammation1–3. -

The Role of the Vaginal Microbiome in Distinguishing Female Chronic Pelvic Pain Caused by Endometriosis/Adenomyosis

771 Original Article Page 1 of 12 The role of the vaginal microbiome in distinguishing female chronic pelvic pain caused by endometriosis/adenomyosis Xiaopei Chao1,2, Yang Liu1,2, Qingbo Fan1,2, Honghui Shi1,2, Shu Wang1,2, Jinghe Lang1,2 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH), Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China; 2National Clinical Research Center for Obstetric & Gynecologic Diseases, Beijing, China Contributions: (I) Conception and design: S Wang, J Lang; (II) Administrative support: S Wang, Q Fan, H Shi; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: X Chao, Y Liu; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: X Chao, S Wang; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: X Chao, S Wang; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Shu Wang; Jinghe Lang. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Shuaifuyuan No. 1, Dongcheng District, Beijing 100730, China. Email: [email protected]; [email protected]. Background: This study aimed to investigate the specific vaginal microbiome in the differential diagnosis of endometriosis/adenomyosis (EM/AM)-associated chronic pelvic pain (CPP) from other types of CPP, and to explore the role of the vaginal microbiome in the mechanism of EM/AM-associated CPP. Methods: We recruited 37 women with EM/AM-associated CPP, 25 women with chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) without EM/AM, and 66 women without CPPS into our study. All of the participants were free from human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. Sequencing of barcoded 16S rRNA gene fragments (V4) was used to determine the vaginal microbiome composition on the Illumina HiSeq2500 System. -

Impact of the Post-Transplant Period and Lifestyle Diseases on Human Gut Microbiota in Kidney Graft Recipients

microorganisms Article Impact of the Post-Transplant Period and Lifestyle Diseases on Human Gut Microbiota in Kidney Graft Recipients Nessrine Souai 1,2 , Oumaima Zidi 1,2 , Amor Mosbah 1, Imen Kosai 3, Jameleddine El Manaa 3, Naima Bel Mokhtar 4, Elias Asimakis 4 , Panagiota Stathopoulou 4 , Ameur Cherif 1 , George Tsiamis 4 and Soumaya Kouidhi 1,* 1 Laboratory of Biotechnology and Valorisation of Bio-GeoRessources, Higher Institute of Biotechnology of Sidi Thabet, BiotechPole of Sidi Thabet, University of Manouba, Ariana 2020, Tunisia; [email protected] (N.S.); [email protected] (O.Z.); [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (A.C.) 2 Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences of Tunis, University of Tunis El Manar, Farhat Hachad Universitary Campus, Rommana 1068, Tunis, Tunisia 3 Unit of Organ Transplant Military Training Hospital, Mont Fleury 1008, Tunis, Tunisia; [email protected] (I.K.); [email protected] (J.E.M.) 4 Laboratory of Systems Microbiology and Applied Genomics, Department of Environmental Engineering, University of Patras, 2 Seferi St, 30100 Agrinio, Greece; [email protected] (N.B.M.); [email protected] (E.A.); [email protected] (P.S.); [email protected] (G.T.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +216-95-694-135 Received: 8 September 2020; Accepted: 30 October 2020; Published: 4 November 2020 Abstract: Gaining long-term graft function and patient life quality remain critical challenges following kidney transplantation. Advances in immunology, gnotobiotics, and culture-independent molecular techniques have provided growing insights into the complex relationship of the microbiome and the host. However, little is known about the over time-shift of the gut microbiota in the context of kidney transplantation and its impact on both graft and health stability.