Sector Policing on the West Rand – Three Case Studies Executive Summary 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1-35556 3-8 Padp1 Layout 1

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA August Vol. 566 Pretoria, 3 2012 Augustus No. 35556 PART 1 OF 3 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure G12-088869—A 35556—1 2 No. 35556 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 3 AUGUST 2012 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the senderʼs respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 35556 Menlyn..................................................... 3 35556 Applications concerning Operating -

Westonaria SAPS in Carletonville Cluster

10 July 2009, RANDFONTEIN HERALD Page 5 Westonaria SAPS in Carletonville cluster Westonaria — Following the incor- above crimes reported in the whole poration of Merafong into Gauteng, cluster, on a weekly basis. Carletonville SAPS has now be- This team will work from the Uni- come the accountable station for all cus Building under the command of other stations in its cluster, includ- Superintendent Reginald Shabangu. ing Westonaria. "The Roadblock Task team consists The Carletonville SAPS cluster of 20 members from each of the consists of Khutsong, Fochville, station's crime prevention units and Wedela and now Westonaria police will concentrate their efforts on major station. routes such as the N12 and the Carletonville SAPS spokesman, P111." Sergeant Busi Menoe, says there will She adds that the main purpose of also be an overall commander for the this task team will be to prevent whole cluster. crimes such as house robberies, car "At this stage there is an interim hijackings and business robberies. acting cluster commander, Director "They will also be on the look-out Fred Kekana, who is based at the for stolen property and vehicles." Station Commissioner, Director Patricia Rampota, salutes Captain Richard Vrey during the Randfontein Westonaria station." Menoe says these members are di- SAPS medal parade. Menoe adds that two task teams vided into two groups under the com- have also been established to fight mand of captains Robert Maphasha crime in the whole cluster, namely the and Lot Nkoane. SAPS members honoured at parade Trio Task team and the Roadblock "The two groups will work flexi- Task team. -

Local Government and Housing

Vote 7: Local Government and Housing VOTE 7 LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND HOUSING Infrastructure to be appropriated R4 058 777 000 Responsible MEC MEC for Local Government and Housing Administering department Department of Local Government and Housing Accounting officer Head of Department 1. STRATEGIC OVERVIEW OF INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAMME Strategic Overview There has been a shift in focus from the provision of housing to the establishment of sustainable human settlements due to the fact that previous policies to address housing did not adequately address the housing needs within the context of the brooder socio-economic needs of communities. In an effort to address this inconsistency gap, Cabinet approved the Comprehensive Plan for the Development of Human Settlements in 2004 which provides the framework to address housing needs within the context of broader socio-economic needs resulting in sustainable human settlements. The Comprehensive Plan is supplemented by the following business plans, which in turn informs the department’s infrastructure programme: • Stimulating the Residential Property Market; • Spatial Restructuring and Sustainable Human Settlements; • Social (Medium-Density) Housing Programme; • Informal Settlement Upgrading Programme; • Institutional Reform and Capacity Building; • Housing Subsidy Funding System Reforms; and • Housing and Job Creation. The following functional areas have been identified as the basis for the roll out of the infrastructure programme: • Service Delivery and Development Targets – the department will accelerate its current programmes of Mixed Housing Developments, Eradication of Informal Settlements, Alternative Tenure, Rural Housing, Urban Renewal Programme and the 20 Prioritised Township Programme to address historical backlogs in basic services, housing and infrastructure. • Capacity Building and Hands on Support – the department will strengthen its support to municipalities to ensure that the municipal capacity to deliver basic service is achieved and service delivery is realised. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Building Statistics October 2002

Statistical release P5041.1 Building statistics October 2002 Co-operation between Statistics South Africa Embargo: 13:00 (Stats SA), the citizens of the country, the private sector and government institutions is essential for Date: 18 December 2002 a successful statistical system. Without continued co-operation and goodwill, the timely release of relevant and reliable official statistics will not be possible. Stats SA publishes approximately three hundred different releases each year. It is not economically viable to produce them in more than one of South Africa’s eleven official languages. Since the releases are used extensively, not only locally, but also by international economic and social- scientific communities, Stats SA releases are published in English only. ¢¡¤£ ¥§¦©¨¤ ¦ ¡ ¨¤¡¤£ ¦¢ ! "#¨%$ &'¡¤£ ()¦ * +,&-/. ¡¤£ 1002¨3¡ 3 3¨4 ¢¡ 5¨!¡¤£ ¦ 6 7©8 9;:=<?>A@B1C;>DFE4C¤GIHKJLCMC NO!P :=<?>A@B1C;>DQE4C¤GIHSRLR4T U#V%W ¦¢£ X3¦§.?.!¡ 10#0/Y2£Z-2'©[0\¨¦?¨]0?0/¦§^ ?/¥ ^ _`¦ aS 2b#0©£ ¨¤ 1Y2$`¨¤¨%c`Y d`d§ee4e^ 0/¨f¦©¨]0/0\¦ ^ ?/¥g^ _`¦ 1 P5041.1 Key figures regarding building plans passed for the month ended October 2002 Actual estimates at January Percentage Percentage Percentage constant 2000 2002 change change change prices October to between between between 2002 October October 2001 August 2001 to January 2001 to 2002 and October 2001 October 2001 October 2002 and and August 2002 to January 2002 to R million R million October 2002 October 2002 Residential buildings Dwelling-houses 855,8 7 122,5 + 18,2 + 17,8 + 10,5 Flats and townhouses -

Mother-Tongue Education in a Multilingual Township: Possibilities for Recognising Lok'shin Lingua in South Africa

Reading & Writing - Journal of the Reading Association of South Africa ISSN: (Online) 2308-1422, (Print) 2079-8245 Page 1 of 10 Original Research Mother-tongue education in a multilingual township: Possibilities for recognising lok’shin lingua in South Africa Author: Background: Mother-tongue education in South African primary schools remains a 1 Rockie Sibanda challenge to policymakers. The situation is problematic in multilingual lok’shin (township) Affiliation: schools where the lok’shin lingua is not recognised as ‘standard’ language. This article Department of Languages, raises the controversial possibility of positioning of lok’shin lingua in a formal education Cultural Studies and Applied langscape. Linguistics, Faculty of Humanities, University of Objectives: The article’s first purpose is to highlight recent international and local research Johannesburg, Johannesburg, which depicts controversies surrounding mother tongue instruction in primary schools. The South Africa second purpose is to conceptualise lok’shin lingua as a dialect present in children’s everyday Corresponding author: vocabulary. Rockie Sibanda, [email protected] Method: Data was gathered through a qualitative approach using interviews. The interviews were conducted with parents and educators at a township in South Africa. Dates: Received: 14 Dec. 2018 Results: Findings show notable differences in school language of instruction and the languages Accepted: 10 June 2019 children speak outside school. Published: 29 Aug. 2019 Conclusion: Mother tongue teaching is problematic as it is incongruent with learners’ language How to cite this article: repertoires. Therefore, a call is made for the recognition of lok’shin lingua in educational Sibanda, R., 2019, contexts as a way to promote more research into mother-tongue education. -

Randfontein Main Seat of Randfontein Magisterial District

# # !C # # # # # ^ !C # !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ^ # # !C # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # # # # # # # # !C# # # ## # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # ^ # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # !C # #!C # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ### # !C # # !C # # # # !C # # ## ## !C # # !C !. # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # ^ # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # !C !C## # # # # # # # !C # # # # !C# # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # ^ # ## !C # # # !C #!C ## # # # # # # # # # ## # # # ## # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # -

ALL PUBLIC CERTIFIED ADULT LEARNING CENTRES in GAUTENG Page 1 of 8

DISTRICTS ABET CENTRE CENTRE TEL/ CELL PHYSICAL MUNICIPAL MANAGER ADDRESSES BOUNDARY Gauteng North - D1 / GN Taamane PALC Mr. Dladla D.A. (013) 935 3341 Cnr Buffalo & Gen Louis Bapsfontein, 5th Floor York Cnr. Park Van Jaan, Hlabelela, Zivuseni, 073 342 9798 Botha Baviaanspoort, Building Mandlomsobo, Vezu;wazi, [email protected] Bronkhorstspruit, 8b water Meyer street Mphumelomuhle, Rethabiseng, Clayville, Cullinan, Val de Grace Sizanani, Vezulwazi, Enkangala, GPG Building Madibatlou, Wozanibone, Hammanskraal, Pretoria Kungwini, Zonderwater Prison, Premier Mine, Tel: (012) 324 2071 Baviaanspoort Prison A & B. Rayton, Zonderwater, Mahlenga, Verena. Bekkersdal PALC Mr. Mahlatse Tsatsi Telefax: (011) 414-1952 3506 Mokate Street Gauteng West - D2 / GW Simunye, Venterspost, 082 878 8141 Mohlakeng Van Der Bank, Cnr Human & Boshoff Str. Bekkersdal; Westonaria, [email protected] Randfontein Bekkersdal, Krugersdorp 1740 Zuurbekom, Modderfontein, Brandvlei, Tel: (011) 953 Glenharvie, Mohlakeng, Doringfontein, 1313/1660/4581 Lukhanyo Glenharvie, Mosupatsela High Hekpoort, Kagiso PALC Mr. Motsomi J. M. (011) 410-1031 School Krugersdorp, Azaadville, Azaadville Sub, Fax(011) 410-9258 9080 Sebenzisa Drive Libanon, Khaselihle, Maloney’s Eye, 082 552 6304 Kagiso 2 Maanhaarrand, Silverfields, Sizwile, Sizwile 073 133 4391 Magaliesberg, Sub, Tsholetsega, [email protected] Mohlakeng, Tsholetsega Sub, Khaselihle Muldersdrift, Sub, Silverfieds Sub, Oberholzer, Munsieville. Randfontein, Randfontein South,The Village, Toekomsrus, Khutsong/ Motebong PALC Mr. S. F. Moleko fax:018 7830001 Venterspos, Mohlakeng, Badirile, 082 553 9580 3967 Nxumalo Road Western Areas, ALL PUBLIC CERTIFIED ADULT LEARNING CENTRES IN GAUTENG Page 1 of 8 Toekomsrus, Zenzele. Wedela, Telefax: (018) 788-5180 Khutsong Westonaria, 076 709 0469 Azaadville, Lebanon [email protected] Wedela/ Fochville PALC MS. A.Senoamadi Wedela, Sediegile Fax: (018) 780 1397 363 Ben Shibure 078 6155390 Avenue Kokosi Fochville Tshwane North - D3 / TN Gaerobe PALC Mr. -

The Needs of Unemployed Youth on the West Rand

THE NEEDS OF UNEMPLOYED YOUTH ON THE WEST RAND by SARAH IMELDA MAPHARAMI MARIBE SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN COMMUNITY WORK IN THE FACULTY OF ARTS AT THE RAND AFRIKAANS UNIVERSITY STUDY LEADER: DR C B FOUCHE MAY 1996 ( ) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I ACKNOWLEDGE WITH THANKS, APPRECIATION AND ADMIRATION THE ASSISTANCE I RECEIVED' FROM THE FOLLOWING PEOPLE FOR HAVING MADE IT POSSIBLE FOR ME TO COMPLETE MY STUDIES. THE ALMIGHTY GOD FOR THE SUPPORT AND GUIDANCE HE GAVE ME THROUGHOUT THE ACADEMIC YEAR. MY STUDY LEADER, DR FOUCHE, FOR HER PATIENCE, GUIDANCE AND MOTIVATION, NOT FORGETTING HER FRIENDLY ATTITUDE. DR NEL AND ALL MY TUTORS FOR THE KNOWLEDGE THEY SHARED . WITH ME. MY LATE MUM, DAD, BROTHER AND SISTERS, FOR HAVING GIVEN ME THEIR SUPPORT THROUGHOUT MY STUDY LIFE. TO MY FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES, MPULE MOILOA, MAGDA ERASMUS, 'MAPULE MACHE AND DOLLY MASELOANE FOR THEIR BOORS, STUDY MATERIAL, SUPPORT AND GUIDANCE. OPSOMMING 1. INLEIDING: Die werkloosheid in Suid-Afrika is omvangryk en die behoefte bestaan dat die probleem op alle vlakke aangespreek behoort te word. Baie jongmense is onsuksesvol in hulle soeke na werk en wend hulle dan tot kriminele aktiwiteite om te oorleef. Daar bestaan noue verband tussen misdaad en werkloosheid en dit wek kommer. Oortredings begaan deur die jeugdige oortreder wissel van diefstal, roof en moord. Die toename in kriminele aktiwiteite deur die jeugdige word waargeneem. Misdaad het met 27% tussen die jare 1987 en 1992 toegeneem. Hiermee saam het geweld ook met 19% gestyg. (Glanz, 1993). Die Departement van Statistiek bereken egter dat 95398 jeugdiges tussen die ouderdom van sewe en twintig jaar gedurende 1 Julie 1990 en 30 Junie 1991 by kriminele aktiwiteite betrokke was. -

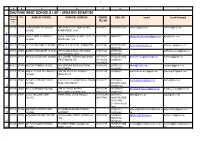

Gauteng West Schools List

1 A B C D F H I J 1 GAUTENG WEST SCHOOLS LIST - UPDATED 2016/01/20 Paypoint/ Emis NAME OF SCHOOL PHYSICAL ADDRESS SCHOOL CELL NO email Email Principal compone nt nr TEL NO 2 902009 270595 AB PHOKOMPE SECONDARY 7440 SEME STREET, MOHLAKENG, 0114140002 0825536025 GDE [email protected] [email protected] SCHOOL RANDFONTEIN, 1759 3 902010 250027 AHMED TIMOL SECONDARY CNR OF KOHINOOR & KISMET STREET, 0114131323 0845815813 [email protected] [email protected] SCHOOL AZAADVILLE, 1750 4 902011 251199 ATLHOLANG PRIMARY SCHOOL 9079 SEBENZISA DRIVE, KAGISO 1754 0114101963 0825572384 GDE [email protected] [email protected] 6 0849412066 902012 270603 BADIRILE SECONDARY SCHOOL 3759 NXUMALO ROAD, KHUTSONG, 0187831564 0825558846 [email protected] 8 CARLETONVILLE 2499 0825532065 902013 251231 BOIPELO SECONDARY SCHOOL 4113 CORNER THEMBA & MOGOROSI 0114101001 0825558050 GDE [email protected] [email protected] DRIVE, KAGISO 1754 0114102916 0825555080 10 0114108066 902001 271478 BOITEKO PRIMARY SCHOOL 5840 SOMPANE ROAD, KHUTSONG, 0187833350 0825572339 [email protected] [email protected] 11 WESTONARIA 0832406970 902015 251264 BOSELE PUBLIC INTERMEDIATE 1676 THEMBA DRIVE, KAGISO 2, 0114101269 0825564401 [email protected] [email protected] SCHOOL MOGALE CITY 12 902016 270645 BRANDVLEI PRIMARY FARM PLOT 55 VENTERSDORP/RUSTENBURG 0114162122 0827216894 [email protected] [email protected] SCHOOL ROAD, RANDFONTEIN 0825542389 GDE 13 0731959492b 902017 270652 BULELANI PRIMARY SCHOOL 2189 RALERATA STREET, 0114141190 071 347 6165 [email protected] [email protected] 14 MOHLAKENG, RANDFONTEIN 0114141140 0824837932 902018 270041 CARLETON JONES HIGH ANNAN ROAD, CARLETONVILLE 0187883239/0 0825533315 [email protected] [email protected] SCHOOL 0845157440 0828517969 GDE 082 8517970 (0713647516 Dept 16 Dries) 902019 251306 DIE POORT PRIMARY FARM RUSTENBURG AND BRITS ROAD, 0710557514 [email protected]. -

Comparative Study on Metropolitan Governance PRESENTATION

REPORT 2014 Comparative Study on Metropolitan Governance PRESENTATION The new world economic order is structured on a network of cities that in a competitive scenario share the same desire: to ensure good quality of life for its inhabitants, to have good functional performance and ability to attract new investments. The challenge has mobilized governments around the world in the search for solutions to their global metropolises. After all, these are complex places that while concentrate numerous opportunities also generate profound inequalities. Three years ago, the São Paulo Company for Metropolitan Planning – Emplasa – started to coordinate the Metropolis Initiave on Metropolitan Governance, developing comparative researches and technical works with over 19 partners representing metropolitan regions of Brazil and the world. As a result, now we present the Study of Metropolitan Governance, focusing on viable alternatives for metropolitan projects. The material identifies the different international practices and brings the partners experiences and lessons learned related to governance and funding of metropolitan projects. The work is not restricted to a purely theoretical approach of the topic. The idea is to list the practical cases capable of being replicated, with the appropriate adaption, to other metropolitan regions. Emplasa is a reference public company when it comes to metropolitan planning and has been signing their positioning at the state, national and international scene, getting to know new projects that can improve the already conducted practices and offer their expertise to other regions and countries. With an active global insertion, Emplasa participated in several Metropolis events presenting our internal projects and the work from the Initiative on Metropolitan Governance. -

EPISCOPAL CHURCHPEOPLE for a I=REE SOUTHERN AFRICA ·E 339 Lafayette Street, New York, N.Y

EPISCOPAL CHURCHPEOPLE for a i=REE SOUTHERN AFRICA ·E 339 Lafayette Street, New York, N.Y. 10012·2725 C (212) 4n-0066 S A #50 10 December 1986 CHILDREN UNDER REPRESSION These horrifying facts about the Pretoria regime's treatment of black South African young people have been exhaustively researched and just published un- , der the auspices of the Detainees' Parents Support Committee by a group-of ' people and organizations who have been active in the monitoring, care and treatment of detainees and their families. This document - 220 pages long - examines the pOlitical context of repress ion, the complex web of laws under which black people in South Africa must suffer, including the vast powers of the security apparatus, citizenship laws which dispossess people, and the powers of banning; the central role of South Africa's inferior schooling system in igniting black youths' resistance to' the entire apartheid structure;and the damage to the children by the brutality and repression to which they are subjected. Human rights groups in South Africa have underway a campaign to draw urgent', attention to children in detention. ,Pretoria has had to respond to 'domestic,'" and growing world concern - by trying to downplay the issue. Arid by attack;;, "::, ing those pressing the campaign . Officials of the Black Sashano the DPSC,,:, have just been given banning orders,~ notably Ms Audrey Coleman of the DPSC who has devoted years of work for young people in detention. ' , Your' help is needed to help the children of South Africa. Attached hereto is a partial list of young detainees. Choose a name (or names') and write urging their immediate release, to: President P.