Folklife Center News Fall 2002 • Volume Xxiv, Number 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the 2016 Gubernatorial Elections by Jennifer M

GOVERNORS The National Mood and the Seats in Play: Understanding the 2016 Gubernatorial Elections By Jennifer M. Jensen and Thad Beyle With a national anti-establishment mood and 12 gubernatorial elections—eight in states with a Democrat as sitting governor—the Republicans were optimistic that they would strengthen their hand as they headed into the November elections. Republicans already held 31 governor- ships to the Democrats’ 18—Alaska Gov. Bill Walker is an Independent—and with about half the gubernatorial elections considered competitive, Republicans had the potential to increase their control to 36 governors’ mansions. For their part, Democrats had a realistic chance to convert only a couple of Republican governorships to their party. Given the party’s win-loss potential, Republicans were optimistic, in a good position. The Safe Races North Dakota Races in Delaware, North Dakota, Oregon, Utah Republican incumbent Jack Dalrymple announced and Washington were widely considered safe for he would not run for another term as governor, the incumbent party. opening the seat up for a competitive Republican primary. North Dakota Attorney General Wayne Delaware Stenehjem received his party’s endorsement at Popular Democratic incumbent Jack Markell was the Republican Party convention, but multimil- term-limited after fulfilling his second term in office. lionaire Doug Burgum challenged Stenehjem in Former Delaware Attorney General Beau Biden, the primary despite losing the party endorsement. eldest son of former Vice President Joe Biden, was Lifelong North Dakota resident Burgum had once considered a shoo-in to succeed Markell before founded a software company, Great Plains Soft- a 2014 recurrence of brain cancer led him to stay ware, that was eventually purchased by Microsoft out of the race. -

Race & Ethnicity in America

RACE & ETHNICITY IN AMERICA TURNING A BLIND EYE TO INJUSTICE Cover Photos Top: Farm workers labor in difficult conditions. -Photo courtesy of the Farmworker Association of Florida (www.floridafarmworkers.org) Middle: A march to the state capitol by Mississippi students calling for juvenile justice reform. -Photo courtesy of ACLU of Mississippi Bottom: Officers guard prisoners on a freeway overpass in the days after Hurricane Katrina. -Photo courtesy of Reuters/Jason Reed Race & Ethnicity in America: Turning a Blind Eye to Injustice Published December 2007 OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS Nadine Strossen, President Anthony D. Romero, Executive Director Richard Zacks, Treasurer ACLU NATIONAL OFFICE 125 Broad Street, 18th Fl. New York, NY 10004-2400 (212) 549-2500 www.aclu.org TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 13 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 15 RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE UNITED STATES 25 THE FAILURE OF THE UNITED STATES TO COMPLY WITH THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION 31 ARTICLE 1 DEFINITION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION 31 U.S. REDEFINES CERD’S “DISPARATE IMPACT” STANDARD 31 U.S. LAW PROVIDES LIMITED USE OF DOMESTIC DISPARATE IMPACT STANDARD 31 RESERVATIONS, DECLARATIONS & UNDERSTANDINGS 32 ARTICLE 2 ELIMINATE DISCRIMINATION & PROMOTE RACIAL UNDERSTANDING 33 ELIMINATE ALL FORMS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION & PROMOTE UNDERSTANDING (ARTICLE 2(1)) 33 U.S. MUST ENSURE PUBLIC AUTHORITIES AND INSTITUTIONS DO NOT DISCRIMINATE 33 U.S. MUST TAKE MEASURES NOT TO SPONSOR, DEFEND, OR SUPPORT RACIAL DISCRIMINATION 34 Enforcement of Employment Rights 34 Enforcement of Housing and Lending Rights 36 Hurricane Katrina 38 Enforcement of Education Rights 39 Enforcement of Anti-Discrimination Laws in U.S. Territories 40 Enforcement of Anti-Discrimination Laws by the States 41 U.S. -

Alabama at a Glance

ALABAMA ALABAMA AT A GLANCE ****************************** PRESIDENTIAL ****************************** Date Primaries: Tuesday, June 1 Polls Open/Close Must be open at least from 10am(ET) to 8pm (ET). Polls may open earlier or close later depending on local jurisdiction. Delegates/Method Republican Democratic 48: 27 at-large; 21 by CD Pledged: 54: 19 at-large; 35 by CD. Unpledged: 8: including 5 DNC members, and 2 members of Congress. Total: 62 Who Can Vote Open. Any voter can participate in either primary. Registered Voters 2,356,423 as of 11/02, no party registration ******************************* PAST RESULTS ****************************** Democratic Primary Gore 214,541 77%, LaRouche 15,465 6% Other 48,521 17% June 6, 2000 Turnout 278,527 Republican Primary Bush 171,077 84%, Keyes 23,394 12% Uncommitted 8,608 4% June 6, 2000 Turnout 203,079 Gen Election 2000 Bush 941,173 57%, Gore 692,611 41% Nader 18,323 1% Other 14,165, Turnout 1,666,272 Republican Primary Dole 160,097 76%, Buchanan 33,409 16%, Keyes 7,354 3%, June 4, 1996 Other 11,073 5%, Turnout 211,933 Gen Election 1996 Dole 769,044 50.1%, Clinton 662,165 43.2%, Perot 92,149 6.0%, Other 10,991, Turnout 1,534,349 1 ALABAMA ********************** CBS NEWS EXIT POLL RESULTS *********************** 6/2/92 Dem Prim Brown Clinton Uncm Total 7% 68 20 Male (49%) 9% 66 21 Female (51%) 6% 70 20 Lib (27%) 9% 76 13 Mod (48%) 7% 70 20 Cons (26%) 4% 56 31 18-29 (13%) 10% 70 16 30-44 (29%) 10% 61 24 45-59 (29%) 6% 69 21 60+ (30%) 4% 74 19 White (76%) 7% 63 24 Black (23%) 5% 86 8 Union (26%) -

Montana Freemason

Montana Freemason Feburary 2013 Volume 86 Number 1 Montana Freemason February 2013 Volume 86 Number 1 Th e Montana Freemason is an offi cial publication of the Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Montana. Unless otherwise noted,articles in this publication express only the private opinion or assertion of the writer, and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the Grand Lodge. Th e jurisdiction speaks only through the Grand Master and the Executive Board when attested to as offi cial, in writing, by the Grand Secretary. Th e Editorial staff invites contributions in the form of informative articles, reports, news and other timely Subscription - the Montana Freemason Magazine information (of about 350 to 1000 words in length) is provided to all members of the Grand Lodge that broadly relate to general Masonry. Submissions A.F.&A.M. of Montana. Please direct all articles and must be typed or preferably provided in MSWord correspondence to : format, and all photographs or images sent as a .JPG fi le. Only original or digital photographs or graphics Reid Gardiner, Editor that support the submission are accepted. Th e Montana Freemason Magazine PO Box 1158 All material is copyrighted and is the property of Helena, MT 59624-1158 the Grand Lodge of Montana and the authors. [email protected] (406) 442-7774 Deadline for next submission of articles for the next edition is March 30, 2013. Articles submitted should be typed, double spaced and spell checked. Articles are subject to editing and Peer Review. No compensation is permitted for any article or photographs, or other materials submitted for publication. -

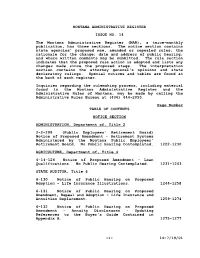

MAR), a Twice-Monthly Publication, Has Three Sections

MONTANA ADMINISTRATIVE REGISTER ISSUE NO. 14 The Montana Administrative Register (MAR), a twice-monthly publication, has three sections. The notice section contains state agencies' proposed new, amended or repealed rules; the rationale for the change; date and address of public hearing; and where written comments may be submitted. The rule section indicates that the proposed rule action is adopted and lists any changes made since the proposed stage. The interpretation section contains the attorney general's opinions and state declaratory rulings. Special notices and tables are found at the back of each register. Inquiries regarding the rulemaking process, including material found in the Montana Administrative Register and the Administrative Rules of Montana, may be made by calling the Administrative Rules Bureau at (406) 444-2055. Page Number TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTICE SECTION ADMINISTRATION, Department of, Title 2 2-2-299 (Public Employees' Retirement Board) Notice of Proposed Amendment - Retirement Systems Administered by the Montana Public Employees' Retirement Board. No Public Hearing Contemplated. 1222-1230 AGRICULTURE, Department of, Title 4 4-14-124 Notice of Proposed Amendment - Loan Qualifications. No Public Hearing Contemplated. 1231-1243 STATE AUDITOR, Title 6 6-130 Notice of Public Hearing on Proposed Adoption - Life Insurance Illustrations. 1244-1258 6-131 Notice of Public Hearing on Proposed Amendment, Repeal and Adoption - Life Insurance and Annuities Replacement. 1259-1274 6-132 Notice of Public Hearing on Proposed Amendment - Annuity Disclosures - Updating References to the Buyer's Guide Contained in Appendix A. 1275-1277 -i- 14-7/19/01 Page Number COMMERCE, Department of, Title 8 8-119-7 (Travel Promotion and Development Division) Notice of Proposed Amendment - Tourism Advisory Council. -

57Th Montana Legislature: News Coverage of the 2001 Session

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2001 57th Montana Legislature: News coverage of the 2001 session Ericka Schenck Smith The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Ericka Schenck, "57th Montana Legislature: News coverage of the 2001 session" (2001). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5169. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5169 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike . The University of MdDnnttannai Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, , provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes” or "No" and provide signature Yes, I grant permission ^ No, I do not grant permission ________ Author’s Signature: Date: <9*1 <£x3F) I______ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with ' the author's explicit consent. 8/98 The 57th Montana Legislature: News Coverage of the 2001 Session by Ericka Schenck Smith B.A. Montana State University-Bozeman, 1997 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana May 2001 Char Dean, Graduate School S*3l-ov Date UMI Number: EP40633 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Trading Off the Benefits and Burdens: Coal Development in the Transboundary Flathead River Valley

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2012 TRADING OFF THE BENEFITS AND BURDENS: COAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE TRANSBOUNDARY FLATHEAD RIVER VALLEY Nadia E. Soucek The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Soucek, Nadia E., "TRADING OFF THE BENEFITS AND BURDENS: COAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE TRANSBOUNDARY FLATHEAD RIVER VALLEY" (2012). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1134. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1134 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRADING OFF THE BENEFITS AND BURDENS: COAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE TRANSBOUNDARY FLATHEAD RIVER VALLEY By NADIA ELISE SOUCEK B.A. Politics and Government, University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, Washington, 2009 A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Studies The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2012 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Associate Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. Len Broberg, Chair Environmental Studies Dr. Matthew McKinney Center for Natural Resources & Environmental Policy Dr. Mike S. Quinn Environmental Design, University of Calgary © COPYRIGHT by Nadia Elise Soucek 2012 All Rights Reserved ii Soucek, Nadia, M.S., Spring 2012 Environmental Studies Trading Off the Benefits and Burdens: Coal Development in the Transboundary Flathead River Valley Chairperson: Dr. -

Geographic Perspectives on State-Directed Heritage Production in Twentieth-Century Montana

GEOGRAPHIC PERSPECTIVES ON STATE-DIRECTED HERITAGE PRODUCTION IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY MONTANA by Robert Merrill Briwa A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Earth Sciences MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana November 2019 ©COPYRIGHT by Robert Merrill Briwa 2019 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my mother and brother, Anne S. Briwa and Taylor S. Briwa, who kept things in perspective. And to my father, John T. Briwa, who taught me glacial erratics a lifetime ago. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many to whom I am indebted and who helped make this research happen. Friends in Earth Sciences and beyond (Kelsey, Nick, Kris, Katie B., Katie E., Buzz, Carl, Sylvia, Jen, Dan, Bill, Thomas, Avantika, Benny, and Scotty) were all great sounding boards, writing partners, and bastions of moral support. As always, Taylor and my mother kept cheering me on from home, too, during critical times. I’m lucky to have you all in my life. Staff at the Montana Historical Society, Montana SHPO, Bannack State Park, and Beaverhead County Museum all deserve special thanks for assisting in the research process. Research grants and funding from the Department of Earth Sciences at Montana State University, the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies at Brigham Young University, and the Ivan Doig Center for the Study of Western Lands and Peoples all supported my research. Thanks, too, to committee members Dr. Mary Murphy, Dr. Jamie McEvoy, and Dr. Julia Haggerty. I appreciate your input, patience, support, and flexibility in accommodating my research, much more than a few lines can easily sum up. -

Aviation Awareness Art Contest This YearS Awards Ceremony for the Aviation Awareness Art Contest Was Held on June 19, in Helena

MDT - Department of Transportation Aeronautics Division Vol. 52 No. 7 July 2001 Aviation Awareness Art Contest This years awards ceremony for the Aviation Awareness Art Contest was held on June 19, in Helena. The winners and their families were flown to Helena from their hometowns for this very special event. Lt. Governor Karl Ohs presented the three lucky winners with a trophy, plaque, ribbon and pin. This years winners are Morgan Kinney from Florence, Montana, Morgan will be entering 12th grade at Florence Carlton School and is also the grand prizewinner, which includes paid tuition to attend the 2001 Experimental Aircraft As- sociation Air Academy in Oshkosh, WI and a round trip airline ticket. Samantha Dorne, 7th grader at Salmon Prairie School in Swan Lake was the winner in Category II and Blake Buechler, 3rd grader at Malta Elementary School in Malta was the winner in Category I. Following the awards ceremony all were treated to a tour of the Capitol, lunch and a tour of the Helena Tower before returning Pictured above, left to right, are contest winners Morgan Kinney, Blake Buechler and Crystal & Samantha Dorne, Crystal was the 2nd place winner in Category II (a very home. talented family!). Second & Third place winners are as follows: Lt. Governor Karl Category III Grades 9-12 Ohs, presents Mor- gan Kinney with his nd award, Montana 2 Nathan Hall, Milltown, MT Aeronautics thanks 3rd Elizabeth Semple, Clancy, MT Lt. Governor Ohs for taking part in this Category II Grades 5-8 very special cer- emony. See the artists 2nd Crystal Dorne, Swan Lake, MT winning entries and 3rd Aaron Nicholson, Laurel, MT more contest photos on pages 4 & 5 of the Category III Grades 1-4 newsletter. -

396-058 Interviewee: Greg Jergeson Interviewer: Bob Brown Date of Interview: July 29, 2009 Project: Bob Brown Oral History Collection

Archives and Special Collections Mansfield Library, University of Montana Missoula MT 59812-9936 Email: [email protected] Telephone: (406) 243-2053 This transcript represents the nearly verbatim record of an unrehearsed interview. Please bear in mind that you are reading the spoken word rather than the written word. Oral History Number: 396-058 Interviewee: Greg Jergeson Interviewer: Bob Brown Date of Interview: July 29, 2009 Project: Bob Brown Oral History Collection Bob Brown: This is Bob Brown and I am interviewing Greg Jergeson at his office in the Public Service Commission building in Helena on July 23, 2009. Greg, where were you born? Greg Jergeson: I was born in Havre, St. Jude's Hospital. BB: What year? GJ: 1950. BB: Was there any experience during that 1950s period or maybe the early 1960s, any experience or any person, that piqued your interest in politics, that caused you to become interested in politics and probably ultimately interested you in running for public office? GJ: Well probably, the person that most piqued my interest in public office and public service was Francis Bardanouve. He ran for the first tim e for the legislature and was elected in 1958. And I recall one evening this fellow coming to our door and my folks telling him to stay for dinner, and I could tell that my mom and dad thought the world of this fellow. I couldn't understand Francis very well. I was only eight years old at the time, and here is a fellow that had a speech defect. But, I could tell that my folks could understand him. -

History Bodes Well for Bullock Reelection

Montana Tech Library Digital Commons @ Montana Tech Highlands College Faculty Scholarship 8-27-2015 History Bodes Well for Bullock Reelection Evan Barrett Montana Tech of the University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/lib_studies Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Barrett, Evan, "History Bodes Well for Bullock Reelection" (2015). Highlands College. 66. https://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/lib_studies/66 This News Editorial is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Montana Tech. It has been accepted for inclusion in Highlands College by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Montana Tech. For more information, please contact [email protected]. History Bodes Well for Bullock Reelection Montana Public Radio Commentary by Evan Barrett August 17, 2015 Analyzing historical electoral patterns may seem like an exercise for the back rooms of a university political science department. But active practitioners in the political arena dive into history to find patterns that are indicative, if not predictive, of what might happen in current and future election cycles. While I used to look for such patterns as a political activist involved in the electoral process directly, I now look at them as I prepare for classroom discussion or for historical film making. And a review of Montana election history reveals some patterns that bode well for the reelection of Governor Steve Bullock next year. Over the last 64 years, Governors running for a second full term always win and also always increase their winning margin, often by a lot. One-term Governors during that period – Democrat Forrest Anderson (1972-76), and Republicans Stan Stephens (1988- 92) and Judy Martz (2000-04), all decided on their own not to seek reelection, so they fall out of the analysis. -

Senate Bill No

66th Legislature SB0275 AN ACT PROVIDING THAT A STATUE OR BUST OF MONTANA'S FIRST WOMAN GOVERNOR, JUDY MARTZ, BE PLACED IN THE CAPITOL OR ON THE GROUNDS SURROUNDING THE CAPITOL; REQUIRING PRIVATE FUNDING; AMENDING SECTIONS 2-17-807 AND 2-17-808, MCA; AND PROVIDING FOR CONTINGENT VOIDNESS. WHEREAS, Judy Martz was born on July 28, 1943, in Big Timber, Montana, to Joe and Dorothy Morstein, was raised in Big Timber and Butte, Montana, with her brother, Joe, and her sisters Carol, Penny, Jerrie, and Sherrie, graduated from Butte High School in 1961, and attended Eastern Montana College; and WHEREAS, Judy won the title of Miss Rodeo Montana in 1962 and competed as a member of the 1963 U.S. World Speed Skating Team in Japan and as a member of the 1964 U.S. Olympic Speed Skating Team in Innsbruck, Austria; and WHEREAS, Judy married Harry Martz in 1965 and they became the parents of their son, Justin, and their daughter, Stacey Jo, and is the grandmother of Remy Clair and Rogan; and WHEREAS, Judy and her husband were small business owners in Butte, Montana, for 37 years, and Judy actively participated in the civic affairs of the Butte-Silver Bow region and due to her dedication to the business community, she served as president of the Butte Chamber of Commerce; and WHEREAS, Judy served with great distinction and honor as the first woman Lieutenant Governor of Montana beginning in 1996; and WHEREAS, Judy served with great distinction and honor as the first woman Governor of Montana beginning in 2000; and WHEREAS, Judy boldly proclaimed "Behold the turtle, he only moves forward when he sticks his neck out!" BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF MONTANA: Section 1.