Fuels Management Policy and Practice in the U.S. Forest Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 12: Integrating Ecological and Social Science to Inform Land Management in the Area of the Northwest Forest Plan

Synthesis of Science to Inform Land Management Within the Northwest Forest Plan Area Chapter 12: Integrating Ecological and Social Science to Inform Land Management in the Area of the Northwest Forest Plan Thomas A. Spies, Jonathan W. Long, Peter Stine, Susan to reassess how well the goals and strategies of the Plan are Charnley, Lee Cerveny, Bruce G. Marcot, Gordon Reeves, positioned to address new issues. Paul F. Hessburg, Damon Lesmeister, Matthew J. Reilly, The NWFP was developed in 1993 through a political Martin G. Raphael, and Raymond J. Davis1 process involving scientists in an unusual and controversial role: assessing conditions and developing plan options “We are drowning in information, while starving directly for President Bill Clinton to consider with little for wisdom. The world henceforth will be run by involvement of senior Forest Service managers. The role of synthesizers, people able to put together the right Forest Service scientists in this planning effort is differ- information at the right time, think critically about ent—scientists are now limited to producing a state-of-the- it, and make important choices wisely.” science report in support of plan revision and management —E.O. Wilson, Consilience: The Unity of (USDA FS 2012a), and managers will conduct the assess- Knowledge (1988) ments and develop plan alternatives. Implementation of the NWFP was followed by moni- Introduction toring, research, and expectations for learning and adaptive Long-term monitoring programs and research related to management; however, little formal adaptive management Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP, or Plan) goals, strategies, actually occurred, and the program was defunded after a few and outcomes provide an unprecedented opportunity years. -

Understanding the 2016 Gubernatorial Elections by Jennifer M

GOVERNORS The National Mood and the Seats in Play: Understanding the 2016 Gubernatorial Elections By Jennifer M. Jensen and Thad Beyle With a national anti-establishment mood and 12 gubernatorial elections—eight in states with a Democrat as sitting governor—the Republicans were optimistic that they would strengthen their hand as they headed into the November elections. Republicans already held 31 governor- ships to the Democrats’ 18—Alaska Gov. Bill Walker is an Independent—and with about half the gubernatorial elections considered competitive, Republicans had the potential to increase their control to 36 governors’ mansions. For their part, Democrats had a realistic chance to convert only a couple of Republican governorships to their party. Given the party’s win-loss potential, Republicans were optimistic, in a good position. The Safe Races North Dakota Races in Delaware, North Dakota, Oregon, Utah Republican incumbent Jack Dalrymple announced and Washington were widely considered safe for he would not run for another term as governor, the incumbent party. opening the seat up for a competitive Republican primary. North Dakota Attorney General Wayne Delaware Stenehjem received his party’s endorsement at Popular Democratic incumbent Jack Markell was the Republican Party convention, but multimil- term-limited after fulfilling his second term in office. lionaire Doug Burgum challenged Stenehjem in Former Delaware Attorney General Beau Biden, the primary despite losing the party endorsement. eldest son of former Vice President Joe Biden, was Lifelong North Dakota resident Burgum had once considered a shoo-in to succeed Markell before founded a software company, Great Plains Soft- a 2014 recurrence of brain cancer led him to stay ware, that was eventually purchased by Microsoft out of the race. -

Status and Trend of Late-Successional and Old-Growth Forest

NORTHWEST FOREST PLAN THE FIRST 10 YEARS (1994–2003) Status and Trend of Late-Successional and Old-Growth Forest Melinda Moeur, Thomas A. Spies, Miles Hemstrom, Jon R. Martin, James Alegria, Julie Browning, John Cissel, Warren B. Cohen, Thomas E. Demeo, Sean Healey, Ralph Warbington General Technical Report United States Forest Pacific Northwest D E PNW-GTR-646 E Department of R P A U T RTMENTOFAGRICUL Service Research Station November 2005 Agriculture The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood ,water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the national forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). -

Newsletter Newsletter of the Pacific Northwest Forest Service Retirees—Summer 2015 President’S Message—Jim Rice

OldSmokeys Newsletter Newsletter of the Pacific Northwest Forest Service Retirees—Summer 2015 President’s Message—Jim Rice I had a great career with the U.S. Forest Service, and volunteering for the OldSmokeys now is a opportunity for me to give back a little to the folks and the organization that made my career such a great experience. This past year as President-elect, I gained an understanding about how the organization gets things done and the great leadership we have in place. It has been awesome to work with Linda Goodman and Al Matecko and the dedicated board of directors and various committee members. I am also excited that Ron Boehm has joined us in his new President-elect role. I am looking forward to the year ahead. This is an incredible retiree organization. In 2015, through our Elmer Moyer Memorial Emergency Fund, we were able to send checks to two Forest Service employees and a volunteer of the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest who had lost their homes and all their possessions in a wildfire. We also approved four grants for a little over $8,900. Over the last ten years our organization has donated more than $75,000. This money has come from reunion profits, book sales, investments, and generous donations from our membership. All of this has been given to “non-profits” for projects important to our membership. Last, and most importantly, now is the time to mark your calendars for the Summer Picnic in the Woods. It will be held on August 14 at the Wildwood Recreation Area. -

Race & Ethnicity in America

RACE & ETHNICITY IN AMERICA TURNING A BLIND EYE TO INJUSTICE Cover Photos Top: Farm workers labor in difficult conditions. -Photo courtesy of the Farmworker Association of Florida (www.floridafarmworkers.org) Middle: A march to the state capitol by Mississippi students calling for juvenile justice reform. -Photo courtesy of ACLU of Mississippi Bottom: Officers guard prisoners on a freeway overpass in the days after Hurricane Katrina. -Photo courtesy of Reuters/Jason Reed Race & Ethnicity in America: Turning a Blind Eye to Injustice Published December 2007 OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS Nadine Strossen, President Anthony D. Romero, Executive Director Richard Zacks, Treasurer ACLU NATIONAL OFFICE 125 Broad Street, 18th Fl. New York, NY 10004-2400 (212) 549-2500 www.aclu.org TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 13 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 15 RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE UNITED STATES 25 THE FAILURE OF THE UNITED STATES TO COMPLY WITH THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION 31 ARTICLE 1 DEFINITION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION 31 U.S. REDEFINES CERD’S “DISPARATE IMPACT” STANDARD 31 U.S. LAW PROVIDES LIMITED USE OF DOMESTIC DISPARATE IMPACT STANDARD 31 RESERVATIONS, DECLARATIONS & UNDERSTANDINGS 32 ARTICLE 2 ELIMINATE DISCRIMINATION & PROMOTE RACIAL UNDERSTANDING 33 ELIMINATE ALL FORMS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION & PROMOTE UNDERSTANDING (ARTICLE 2(1)) 33 U.S. MUST ENSURE PUBLIC AUTHORITIES AND INSTITUTIONS DO NOT DISCRIMINATE 33 U.S. MUST TAKE MEASURES NOT TO SPONSOR, DEFEND, OR SUPPORT RACIAL DISCRIMINATION 34 Enforcement of Employment Rights 34 Enforcement of Housing and Lending Rights 36 Hurricane Katrina 38 Enforcement of Education Rights 39 Enforcement of Anti-Discrimination Laws in U.S. Territories 40 Enforcement of Anti-Discrimination Laws by the States 41 U.S. -

Tribal Wildfire Resource Guide

JUNE 2006 re Tribal Wildfi re Resource Guide Developed in Partnership with: Intertribal Timber Council Resource Guide Resource Innovations, University of Oregon Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation Tribal Wildfi “According to the traditional beliefs of the Salish, the Creator put animal beings on the earth before humans. But the world was cold and dark because there was no fi re on earth. The animal beings knew one day human beings would arrive, and they wanted to make the world a better place for them, so they set off on a great quest to steal fi re from the sky world and bring it to the earth.” -Beaver Steals Fire, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Tribal Wildfi re Resource Guide June 2006 Developed in Partnership with: Intertribal Timber Council Written by: Resource Innovations, University of Oregon Graphic Design by: Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation Images from: Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation and the Nez Perce Tribe For thousands of years, Native Americans used fi re as a tool to manage their lands and manipulate vegetation to a desired condition. Tribes once lived harmoniously with nature until the U.S. Federal Government claimed much of their lands and changed the forests from a condition that we would today call “fi re-adapted ecosystems” into the fi re-prone forests that we now see throughout much of western United States. Many forests that were once abundant producers of natural resources are now resource-management nightmares. The cost to manage them now is astronomical compared with the natural method employed by Native Americans. -

Northwest Forest Plan

Standards and Guidelines for Management of Habitat for Late-Successional and Old-Growth Forest Related Species Within the Range of the Northern Spotted Owl Attachment A to the Record of Decision for Amendments to Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management Planning Documents Within the Range of the Northern Spotted Owl Standards and Guidelines for Management of Habitat for Late-Successional and Old-Growth Forest Related Species Within the Range of the Northern Spotted Owl Attachment A to the Record of Decision for Amendments to Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management Planning Documents Within the Range of the Northern Spotted Owl Outline All sections of this document, considered together, are the complete compilation of standards and guidelines. However, these standards and guidelines are broken down into the following sections for clarity and ease of reference. A. Introduction - This section includes introduction, purpose, definition of the planning area, relationship to existing agency plans, introduction to the various land allocation categories used elsewhere in these standards and guidelines, identification of appurtenant maps, and transition standards and guidelines. B. Basis for Standards and Guidelines - This section includes a background discussion of the objectives and considerations for managing for a network of terrestrial reserves. This section also contains the Aquatic Conservation Strategy, which includes discussions of the objectives and management emphases for Riparian Reserves, Key Watersheds, watershed analysis, and watershed restoration. C. Standards and Guidelines - This section includes specific standards and guidelines applicable to all land allocation categories. It also contains descriptions of, and standards and guidelines applicable to, all designated areas, matrix, and Key Watersheds. -

Perceptions of Forestry Alternatives in the US Pacific Northwest

ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 100–115 www.elsevier.com/locate/yjevp Perceptions of forestry alternatives in the US Pacific Northwest: Information effects and acceptability distribution analysis$ Robert G. Ribeà Department of Landscape Architecture, Institute for a Sustainable Environment, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403-5234, USA Available online 10 August 2006 Abstract Conflicts over timber harvesting and clearcutting versus wildlife conservation have instigated alternative silvicultural systems in the US Pacific Northwest. Major forest treatments can be the most controversial element of such systems. A public survey explored the social acceptability of 19 forest treatments that varied by forest age, level of green-tree retention, pattern of retention, and level of down wood. The survey presented respondents with photos of the treatments, explanatory narratives, and resource outputs related to human and wildlife needs. Respondents rated treatments for scenic beauty, service to human needs, service to wildlife needs, and overall acceptability. Acceptability distribution patterns were analysed for all forest treatments. These showed broad, passionate opposition to clearcutting, conflict over the acceptability of not managing forests, conflict over old growth harvests, conflict with some passionate opposition to 15% retention harvests, and unconflicted acceptance of young forest thinnings and 40% retention harvests. Modelling of these responses found that socially acceptable forestry attends to scenic beauty -

Forest Ecology and Management 286 (2012) 171–182

(This is a sample cover image for this issue. The actual cover is not yet available at this time.) This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Forest Ecology and Management 286 (2012) 171–182 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Carbon balance on federal forest lands of Western Oregon and Washington: The impact of the Northwest Forest Plan ⇑ Olga N. Krankina , Mark E. Harmon, Frank Schnekenburger, Carlos A. Sierra 1 Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA article info abstract Article history: The management of federal forest lands in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) region changed in early 1990s Received 12 May 2012 when the Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP) was adopted with the primary goal to protect old-growth forest Received in revised form 8 August 2012 and associated species. A major decline in timber harvest followed, extending an earlier downward trend. -

Alabama at a Glance

ALABAMA ALABAMA AT A GLANCE ****************************** PRESIDENTIAL ****************************** Date Primaries: Tuesday, June 1 Polls Open/Close Must be open at least from 10am(ET) to 8pm (ET). Polls may open earlier or close later depending on local jurisdiction. Delegates/Method Republican Democratic 48: 27 at-large; 21 by CD Pledged: 54: 19 at-large; 35 by CD. Unpledged: 8: including 5 DNC members, and 2 members of Congress. Total: 62 Who Can Vote Open. Any voter can participate in either primary. Registered Voters 2,356,423 as of 11/02, no party registration ******************************* PAST RESULTS ****************************** Democratic Primary Gore 214,541 77%, LaRouche 15,465 6% Other 48,521 17% June 6, 2000 Turnout 278,527 Republican Primary Bush 171,077 84%, Keyes 23,394 12% Uncommitted 8,608 4% June 6, 2000 Turnout 203,079 Gen Election 2000 Bush 941,173 57%, Gore 692,611 41% Nader 18,323 1% Other 14,165, Turnout 1,666,272 Republican Primary Dole 160,097 76%, Buchanan 33,409 16%, Keyes 7,354 3%, June 4, 1996 Other 11,073 5%, Turnout 211,933 Gen Election 1996 Dole 769,044 50.1%, Clinton 662,165 43.2%, Perot 92,149 6.0%, Other 10,991, Turnout 1,534,349 1 ALABAMA ********************** CBS NEWS EXIT POLL RESULTS *********************** 6/2/92 Dem Prim Brown Clinton Uncm Total 7% 68 20 Male (49%) 9% 66 21 Female (51%) 6% 70 20 Lib (27%) 9% 76 13 Mod (48%) 7% 70 20 Cons (26%) 4% 56 31 18-29 (13%) 10% 70 16 30-44 (29%) 10% 61 24 45-59 (29%) 6% 69 21 60+ (30%) 4% 74 19 White (76%) 7% 63 24 Black (23%) 5% 86 8 Union (26%) -

Montana Freemason

Montana Freemason Feburary 2013 Volume 86 Number 1 Montana Freemason February 2013 Volume 86 Number 1 Th e Montana Freemason is an offi cial publication of the Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Montana. Unless otherwise noted,articles in this publication express only the private opinion or assertion of the writer, and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the Grand Lodge. Th e jurisdiction speaks only through the Grand Master and the Executive Board when attested to as offi cial, in writing, by the Grand Secretary. Th e Editorial staff invites contributions in the form of informative articles, reports, news and other timely Subscription - the Montana Freemason Magazine information (of about 350 to 1000 words in length) is provided to all members of the Grand Lodge that broadly relate to general Masonry. Submissions A.F.&A.M. of Montana. Please direct all articles and must be typed or preferably provided in MSWord correspondence to : format, and all photographs or images sent as a .JPG fi le. Only original or digital photographs or graphics Reid Gardiner, Editor that support the submission are accepted. Th e Montana Freemason Magazine PO Box 1158 All material is copyrighted and is the property of Helena, MT 59624-1158 the Grand Lodge of Montana and the authors. [email protected] (406) 442-7774 Deadline for next submission of articles for the next edition is March 30, 2013. Articles submitted should be typed, double spaced and spell checked. Articles are subject to editing and Peer Review. No compensation is permitted for any article or photographs, or other materials submitted for publication. -

MAR), a Twice-Monthly Publication, Has Three Sections

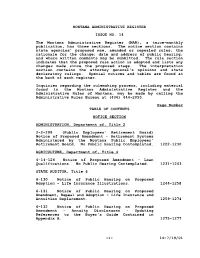

MONTANA ADMINISTRATIVE REGISTER ISSUE NO. 14 The Montana Administrative Register (MAR), a twice-monthly publication, has three sections. The notice section contains state agencies' proposed new, amended or repealed rules; the rationale for the change; date and address of public hearing; and where written comments may be submitted. The rule section indicates that the proposed rule action is adopted and lists any changes made since the proposed stage. The interpretation section contains the attorney general's opinions and state declaratory rulings. Special notices and tables are found at the back of each register. Inquiries regarding the rulemaking process, including material found in the Montana Administrative Register and the Administrative Rules of Montana, may be made by calling the Administrative Rules Bureau at (406) 444-2055. Page Number TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTICE SECTION ADMINISTRATION, Department of, Title 2 2-2-299 (Public Employees' Retirement Board) Notice of Proposed Amendment - Retirement Systems Administered by the Montana Public Employees' Retirement Board. No Public Hearing Contemplated. 1222-1230 AGRICULTURE, Department of, Title 4 4-14-124 Notice of Proposed Amendment - Loan Qualifications. No Public Hearing Contemplated. 1231-1243 STATE AUDITOR, Title 6 6-130 Notice of Public Hearing on Proposed Adoption - Life Insurance Illustrations. 1244-1258 6-131 Notice of Public Hearing on Proposed Amendment, Repeal and Adoption - Life Insurance and Annuities Replacement. 1259-1274 6-132 Notice of Public Hearing on Proposed Amendment - Annuity Disclosures - Updating References to the Buyer's Guide Contained in Appendix A. 1275-1277 -i- 14-7/19/01 Page Number COMMERCE, Department of, Title 8 8-119-7 (Travel Promotion and Development Division) Notice of Proposed Amendment - Tourism Advisory Council.