THE PROSE STYLE of CHARLES LAMB. the Ohio State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Romantic Liberalism

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Romantic Liberalism DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English by Brent Lewis Russo Dissertation Committee: Professor Jerome Christensen, Chair Professor Andrea Henderson Associate Professor Irene Tucker 2014 Chapter 1 © 2013 Trustees of Boston University All other materials © 2014 Brent Lewis Russo TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii CURRICULUM VITAE iv ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION v INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Charles Lamb’s Beloved Liberalism: Eccentricity in the Familiar Essays 9 CHAPTER 2: Liberalism as Plenitude: The Symbolic Leigh Hunt 33 CHAPTER 3: Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Illiberalism and the Early Reform Movement 58 CHAPTER 4: William Hazlitt’s Fatalism 84 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Charles Rzepka and the Trustees of Boston University for permission to include Chapter One of my dissertation, which was originally published in Studies in Romanticism (Fall 2013). Financial support was provided by the University of California, Irvine Department of English, School of Humanities, and Graduate Division. iii CURRICULUM VITAE Brent Lewis Russo 2005 B.A. in English Pepperdine University 2007 M.A. in English University of California, Irvine 2014 Ph.D. in English with Graduate Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Irvine PUBLICATIONS “Charles Lamb’s Beloved Liberalism: Eccentricity in the Familiar Essays.” Studies in Romanticism. Fall 2013. iv ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Romantic Liberalism By Brent Lewis Russo Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Irvine, 2014 Professor Jerome Christensen, Chair This dissertation examines the Romantic beginnings of nineteenth-century British liberalism. It argues that Romantic authors both helped to shape and attempted to resist liberalism while its politics were still inchoate. -

The Lilac Cube

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-21-2004 The Lilac Cube Sean Murray University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Murray, Sean, "The Lilac Cube" (2004). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 77. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/77 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LILAC CUBE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Drama and Communications by Sean Murray B.A. Mount Allison University, 1996 May 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 1 Chapter 2 9 Chapter 3 18 Chapter 4 28 Chapter 5 41 Chapter 6 52 Chapter 7 62 Chapter 8 70 Chapter 9 78 Chapter 10 89 Chapter 11 100 Chapter 12 107 Chapter 13 115 Chapter 14 124 Chapter 15 133 Chapter 16 146 Chapter 17 154 Chapter 18 168 Chapter 19 177 Vita 183 ii The judge returned with my parents. -

A Handlist to the Charles Lamb Society Collection at Guildhall Library

A Handlist to the Charles Lamb Society Collection at Guildhall Library A Handlist to the Charles Lamb Society Collection at Guildhall Library DEBORAH K. HEDGECOCK THE CHARLES LAMB SOCIETY 1995 A Handlist to the Charles Lamb Society Collection at Guildhall Library Copyright Deborah Hedgecock 1995 All rights reserved The Charles Lamb Society 1a Royston Road Richmond Surrey TW10 6LT Registered Charity number 803222: a company limited by guarantee ISSN 0308-0951 Printed by the Stanhope Press, London NW5 (071 387 0041) A Handlist to the Charles Lamb Society Collection at Guildhall Library Contents Preface and Acknowledgements 4 Abbreviations 4 Information on Guildhall Library 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Printed Books 6 2.1 Access conditions 6 2.2 Charles Lamb Society Collection: Printed Books 7 2.2.1 The CLS Pamphlet and Large Pamphlet Collection 8 2.2.2 The CLS Lecture Collection 8 2.2.3 Charles Lamb Society Publications 8 2.2.3.1 Charles Lamb Bulletins 8 2.2.3.2 Indexes to Bulletin 9 2.2.3.3 List of supplements to Bulletin 9 2.2.3.4 Charles Lamb Society Annual Reports and Financial Statements 9 3. Manuscripts 9 3.1 Access conditions 9 3.2.1 18th- and 19th-century autograph letters and manuscripts 10 3.2.2 Facsimiles and reproductions of Lamb's letters 18 3.2.3 20th-century Individuals and Collections 20 3.2.4 The Elian (Society) 25 3.2.5 The Charles Lamb Society Archive 26 4. Prints, Maps and drawings 35 4.1 Access Conditions 35 4.2.1 Framed Pictures 36 4.2.2 Pictures and Ephemera Collection 37 4.2.3 Collections of Pictures 58 4.2.4 Ephemera Cuttings Collection 59 4.2.5 Maps 61 4.2.6 Printing Blocks 61 4.2.7 Glass Slides 61 5. -

The Life and Works of Charles Lamb

DATE DUE Cornell University Library yysj The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924064980240 Edition de Luxe The Life and Works of Charles Lamb IN TWELVE VOLUMES VOLUME X The Letters OF Charles Lamb Newly Arranged, with Additions EDITED, WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY ALFRED AINGER VOLUME II LONDON MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited 1900 All rights reserved This Edition consists of Six Hundred and Seventy-five Copies s 1 CONTENTS CHAPTER II—(Continued) 1800—1809 LETTERS TO COLERIDGE, MANNING, AND OTHERS PAGE LXXX. To Thomas Manning Dec. 13, 1800 i LXXXI. To William Godwin Dec. 14, 1800 4 LXXXII. To Thomas Manning Dec. 16, 1800 6 LXXXIII. „ „ Dec. 27, 1800 9 LXXXIV. To Samuel Taylor Coleridge [No date—end of 1800] 12 LXXXV. To William Words- worth . Jan. 30, 1801 17 LXXXVI. „ „ Jan. 1801 19 LXXXVII. To Robert Lloyd . Feb. 7, 1801 22 LXXXVIII. To Thomas Manning Feb. 15, 180 25 LXXXIX. „ „ [Feb. or Mar. J 1801 30 L. X V b 1 LETTERS OF CHARLES LAMB LETTIR DATE PAGE XC. To Robert Lloyd . April 6, i8or 34 XCI. To Thomas Manning April 1801 38 XCII. To Robert Lloyd , April 1801 40 XCin. To William Godwin June 29, 1801 42 XCIV. To Robert Lloyd . July 26, 1801 43 XCV. To Mr. Walter Wilson Aug. 14, 1801 46 XCVL To Thomas Manning [Aug.] 1801 47 XCVIL „ „ Aug. 31, 1 80 49 XCVin. To William Godwin Sept. -

Charles Lamb's Romantic Collaborations Author(S): Alison Hickey Source: ELH, Vol

Double Bonds: Charles Lamb's Romantic Collaborations Author(s): Alison Hickey Source: ELH, Vol. 63, No. 3 (Fall, 1996), pp. 735-771 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30030122 Accessed: 27/01/2009 15:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jhup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to ELH. http://www.jstor.org DOUBLE BONDS: CHARLES LAMB'SROMANTIC COLLABORATIONS BY ALISONHICKEY Duplex nobis vinculum, et amicitiae et similium junctarumque Camoenarum; quod utinam neque mors solvat, neque temporis longinquitas! -Groscollius "Double is the chain that binds us-both of friendship and of like Muses joined together. -

Numero Kansi Arvostelut Artikkelit / Esittelyt Mielipiteet Muuta 1 (1/2005

Numero Kansi Arvostelut Artikkelit / esittelyt Mielipiteet Muuta -Full Metal Panic (PAN Vision) (Mauno Joukamaa) -DNAngel (ADV) (Kyuu Eturautti) -Final Fantasy Unlimited (PAN Vision) (Jukka Simola) -Kissankorvanteko-ohjeet (Einar -Neon Genesis Evangelion, 2s (Pekka Wallendahl) - Pääkirjoitus: Olennainen osa animen ja -Jin-Roh (Future Film) (Mauno Joukamaa) Karttunen) -Gainax, 1s (?, oletettavasti Pekka Wallendahl) mangan suosiota on hahmokulttuuri (Jari -Manga! Manga! The world of Japanese comics (Kodansha) (Mauno Joukamaa) -Idän ihmeitä: Natto (Jari Lehtinen) 1 -Megumi Hayashibara, 1s (?, oletettavasti Pekka Wallendahl) Lehtinen, Kyuu Eturautti) -Salapoliisi Conan (Egmont) (Mauno Joukamaa) -Kotimaan katsaus: Animeunioni, -Makoto Shinkai, 2s (Jari Lehtinen) - Kolumni: Anime- ja mangakulttuuri elää (1/2005) -Saint Tail (Tokyopop) (Jari Lehtinen) MAY -Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children, 1s (Miika Huttunen) murrosvaihetta, saa nähdä tuleeko siitä -Duel Masters (korttipeli) (Erica Christensen) -Fennomanga-palsta alkaa -Kuukauden klassikko: Saiyuki, 2s (Jari Lehtinen) valtavirta vai floppi (Pekka Wallendahl) -Duel Masters: Sempai Legends (Erica Christensen) -Animea TV:ssä alkaa -International Ragnarök Online (Jukka Simola) -Star Ocean: Till The End Of Time (Kyuu Eturautti) -Star Ocean EX (Geneon) (Kyuu Eturautti) -Neon Genesis Evangelion (PAN Vision) (Mikko Lammi) - Pääkirjoitus: Cosplay on harrastajan -Spiral (Funimation) (Kyuu Eturautti) -Cosplay, 4s (Sefie Rosenlund) rakkaudenosoitus (Mauno Joukamaa) -Hopeanuoli (Future Film) (Jari Lehtinen) -

Dr. Michael Welner's Report on Brian David Mitchell

THE FORENSIC PANEL 224 W. 30 TH ST., SUITE . 806 NEW YORK , NY 10001 TEL : 212.535.9286 FAX : 212.535.3259 MICHAEL WELNER , M.D., CHAIRMAN Brett L. Tolman United States Attorney 185 South State St. Suite 300 Salt Lake City, UT 84111 U.S. vs. Brian David Mitchell June 16, 2009 Dear Mr. Tolman, Pursuant to your request, I have conducted a peer-reviewed forensic psychiatric examination of the above defendant. He is a 55 year old native of Utah charged with kidnapping, kidnapping of a minor, and unlawful transportation of a minor. Brian Mitchell is accused of seizing Elizabeth Smart, then fourteen, and taking her into the mountain wilderness with his wife Wanda Mitchell and then, to Southern California. In the time span preceding Brian Mitchell’s capture, he is alleged to have engaged in forced sex with Elizabeth. Subsequent to his arrest, three examiners filed reports on his competency. On August 30, 2004, with reports having been filed by all expert witnesses, defense and prosecution agreed that Mr. Mitchell was competent to engage in plea negotiations. When plea negotiations failed, the defense modified its position on competency. After competency proceedings in early 2005 in which expert witness mental health professionals testified, Mr. Mitchell was declared incompetent to stand trial in Utah state court on July 22, 2005 by Judge Judith Atherton. On October 10, 2008, the case was transferred to the U.S. District Court of Utah. The United States’ Attorney’s Office subsequently referred this matter to The Forensic Panel for an independent assessment of the following questions: 1) Does Mr. -

Coleridge's Phantom and Fact

COLERIDGE’S PHANTOM AND FACT: TWO NATURES, TRINITARIAN RESOLUTION, AND THE FORMATION OF THE PENTAD TO 1825 BY KIYOSHI TSUCHIYA SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF PH. D. TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF LITERATURE AND THEOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE DECEMBER 1994 © KIYOSHI TSUCHIYA ProQuest Number: 13818408 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818408 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 (oon Csfi^j h(si___ -IIBRAJgy Abstract This thesis discusses how Coleridge develops his trinitarianism, 'God1 'man1, and 'nature', in response to modern philosophies since Descartes, especially to Kant's phenomenology, and how he finally forms the 'Pentad' in 1825. It will have seven chapters. The first chapter discusses his two unexecuted plans, 'the hymns to the elements' (1796) and 'Soother of Absence' (1802-10). It investigates how he comes to think that the hymn, or, the praise of the divine presence in nature, is the original and ideal form of poetry, and how he falls behind his ideal and replaces the first plan with the second. -

Letters of Charles Lamb

LETTERS OF CHARLES LAMB W. J. SYKES F English authors the two best loved are, I suppose, Charles O Dickens and Charles Lamb. Dickens is loved chiefly for what he wrote; Lamb partly for what he wrote, but still more for what he was. Dickens in his novels created an imaginary world of men and women whose sayings and doings move thous ands to laughter or to tears; his novels in extent and popularity far outstrip the works of Lamb, though there are readers, not a few, who would let them all go rather than the Essays of Elia. But as a personality Lamb was infinitely more attractive than Dickens, and it is in his letters that his personality is most fully revealed. 'kt~~ i;;~:I'~i Except by enthusiastic admirers of Lamb, his letters have not been widely read-for the good reason that until the last few years they have not been obtainable in any satisfactory edition. Obviously they were written without any thought of their being collected and published. But friends like Words worth and Coleridge, recognizing their unique quality, pre served most of those they received, and after Lamb's death some began to appear in print. Thus in the Memoir and Letters by TaHourd, and in the collections of Carew, Hazlitt, Percy Fitzgerald, Canon Ainger, and William Macdonald, many were given to the public. All such collections, however, were incom plete; indeed E. V. Lucas, in the preface to his edition of 1905, expressed the opinion that owing to the curious operation of the law of copyright "in order to possess a complete set . -

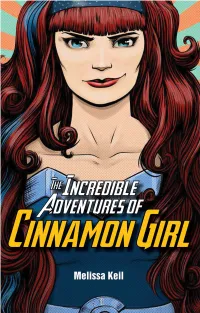

Incredibleadventuresofcinnamo

Cinnamon Girl_int_PRINTER.indd 1 1/13/16 12:12 PM Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2014 by Melissa Keil Illustrations © 2016 by Mike Lawrence First published in Australia in 2014 by Hardie Grant Egmont First United States version published in 2016 by Peachtree Publishers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Design and composition by Nicola Simmonds Carmack Illustrations rendered digitally Printed in February 2016 in the United States of America by RR Donnelley & Sons, Harrisonburg, Virginia. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition ISBN 978-1-56145-905-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Keil, Melissa, author. | Lawrence, Mike (Comic Book artist), illustrator. Title: The incredible adventures of cinnamon girl / Melissa Keil; illustrated by Mike Lawrence. Description: Atlanta, GA : Peachtree Publishers, [2016] | Summary: Alba loves living behind a bakery, drawing comics, and watching bad TV with her friends, but problems arise with certain boys in her life and also, the world might be ending, so as doomsday enthusiasts flock to idyllic Eden Valley, Alba’s life is thrown into chaos. Identifiers: LCCN 2015030680 Subjects: | CYAC: End of the world—Fiction. | Love—Fiction. | Comic books, strips, etc.—Fiction. Classification: LCC PZ7.1.K415 Inc 2016 | DDC [Fic]—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc. -

Gunnerkrigg Court Antimony Is Starting Her First Year of School At

Batman: Bloodstorm Gunnerkrigg Court Muhyo & Roji's Bureau of Supernatural Investi- Prowling the city's darkest corners, the Batman Antimony is starting her first year of school at gloomy gation seeks to destroy an army of vampires before they Gunnerkrigg Court, a very British boarding school that Are you a victim of unwanted spirit possession? Is can feast upon the innocent ... and before he him- has robots running around alongside body-snatching there a ghost you need sent up and away...or down self succumbs to the terrible thirst for human blood. demons, forest gods, and the odd mythical creature. to burn for all eternity? If the answer is yes, then you need Muhyo and Roji, experts in magic law Blood Lad Inu X Boku SS and serving justice to evil spirits is their specialty. Staz is one of the most powerful vampires in the The Maison de Ayakashi is a high security apartment demon world - but secretly, he’s obsessed with building where humans with demon ancestors reside, My Boyfriend is a Monster #5: I Date Dead Peo- human culture, especially video games and manga! each guarded by their own Secret Service bodyguard. ple When a human girl wanders into the demon world A yōkai girl named Ririchiyo moves in hoping for some The Victorian house Nora’s family just bought was and is killed by a demon, Staz vows to help her peace and quiet and is assigned the Secret Service built in the 1870s and guess what? It’s haunted . restore her body and return to her former life .