Carnivores of the World, Second Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classification of Mammals 61

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FORCHAPTER SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Classification © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC 4 NOT FORof SALE MammalsOR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION. 2ND PAGES 9781284032093_CH04_0060.indd 60 8/28/13 12:08 PM CHAPTER 4: Classification of Mammals 61 © Jones Despite& Bartlett their Learning,remarkable success, LLC mammals are much less© Jones stress & onBartlett the taxonomic Learning, aspect LLCof mammalogy, but rather as diverse than are most invertebrate groups. This is probably an attempt to provide students with sufficient information NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FORattributable SALE OR to theirDISTRIBUTION far greater individual size, to the high on the various kinds of mammals to make the subsequent energy requirements of endothermy, and thus to the inabil- discussions of mammalian biology meaningful. -

The Carnivora (Mammalia) from the Middle Miocene Locality of Gračanica (Bugojno Basin, Gornji Vakuf, Bosnia and Herzegovina)

Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-018-0353-0 ORIGINAL PAPER The Carnivora (Mammalia) from the middle Miocene locality of Gračanica (Bugojno Basin, Gornji Vakuf, Bosnia and Herzegovina) Katharina Bastl1,2 & Doris Nagel2 & Michael Morlo3 & Ursula B. Göhlich4 Received: 23 March 2018 /Revised: 4 June 2018 /Accepted: 18 September 2018 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract The Carnivora (Mammalia) yielded in the coal mine Gračanica in Bosnia and Herzegovina are composed of the caniform families Amphicyonidae (Amphicyon giganteus), Ursidae (Hemicyon goeriachensis, Ursavus brevirhinus) and Mustelidae (indet.) and the feliform family Percrocutidae (Percrocuta miocenica). The site is of middle Miocene age and the biostratigraphical interpretation based on molluscs indicates Langhium, correlating Mammal Zone MN 5. The carnivore faunal assemblage suggests a possible assignement to MN 6 defined by the late occurrence of A. giganteus and the early occurrence of H. goeriachensis and P. miocenica. Despite the scarcity of remains belonging to the order Carnivora, the fossils suggest a diverse fauna including omnivores, mesocarnivores and hypercarnivores of a meat/bone diet as well as Carnivora of small (Mustelidae indet.) to large size (A. giganteus). Faunal similarities can be found with Prebreza (Serbia), Mordoğan, Çandır, Paşalar and Inönü (all Turkey), which are of comparable age. The absence of Felidae is worthy of remark, but could be explained by the general scarcity of carnivoran fossils. Gračanica records the most eastern European occurrence of H. goeriachensis and the first occurrence of A. giganteus outside central Europe except for Namibia (Africa). The Gračanica Carnivora fauna is mostly composed of European elements. Keywords Amphicyon . Hemicyon . -

Bobcat LHOTB022604

Life History of the Bobcat LHOTB022604 The bobcat belongs to the family Felidae, which contains mountain lion, Florida panther, ocelot, lynx, jaguar, margay and jaguarundi. Historically the bobcat ranged throughout the lower 48 states and into parts of southern Canada and northern Mexico. Bobcats are found throughout Alabama with greater abundance in the Coastal Plains and Piedmont areas. DESCRIPTION: The bobcat is slightly more than twice the size of a domestic cat. Adult males’ weight ranges between 16-40 pounds and the females between 8-33 pounds. Coloration can vary but generally is yellowish or reddish brown streaked or spotted black or dark brown. The belly and underside of the tail is white. Black spots or bars are found on the belly and inside the forelegs and may extend up the sides to the back. Their tail is short (<5 ¾ inches) with distinct black bars at the tip. REPRODUCTION: Bobcats normally breed once a year from January through March with most births occurring during April and May. After a gestation period of 62 days, a litter of 1-4 kittens is born with 3 kittens being the average litter size. HABITAT: Bobcats are highly adapted to a variety of habitats. They prefer forested habitats with a dense understory and high prey densities. The only habitat type not used is heavily farmed agriculture land. Bobcats are territorial and readily defend their home range. Their home range can vary from 1-80 square miles. Bobcats may use a variety of denning sites such as rock ledges, hollow trees and logs, and brush piles. -

Appendix E.14 Spotlight Surveys Report California Flats Solar Project Spotlight Surveys for San Joaquin Kit Fox and American Badger

Appendix E.14 Spotlight Surveys Report California Flats Solar Project Spotlight Surveys for San Joaquin Kit Fox and American Badger Project # 3308 Prepared for: California Flats Solar, LLC 135 Main Street, 6th Floor San Francisco, CA 94105 Prepared by: H. T. Harvey & Associates April 2014 Cal Poly Technology Park, Bldg. 83, Ste. 1B San Luis Obispo, CA 93407 Ph: 805.756.7400 F: 805.756.7441 Executive Summary The California Flats Solar Project (Project) is a 280-megawatt photovoltaic solar power plant proposed for development in southeastern Monterey County, California. When approved, the solar facility and related operations infrastructure will be built on approximately 1037 hectares (2562 acres) (Project site) of the 29,137-hectare (72,000-acre) Jack Ranch, which is a working cattle ranch. The overall development will include improvements to an existing access road and its connection to State Route 41 (access road/Hwy 41 improvement areas). Together, the Project site and access road/Hwy 41 improvement areas constitute the 1058-hectare (2615-acre) Project impact area (PIA), where all direct, Project-related impacts will occur. A biological study area (BSA) was delineated around the PIA, within which most Project-related biological surveys and assessments are being conducted. The Project site is located within a landscape dominated by gently rolling terrain and grasslands, interspersed with several, mostly ephemeral, riparian corridors and drainages. Numerous wildlife species are known to occur in the region, some of which have been identified as candidate, sensitive, or special-status species in local or regional plans, policies, or regulations, or by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) and/or U.S. -

Phylogeographic and Diversification Patterns of the White-Nosed Coati

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 131 (2019) 149–163 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogeographic and diversification patterns of the white-nosed coati (Nasua narica): Evidence for south-to-north colonization of North America T ⁎ Sergio F. Nigenda-Moralesa, , Matthew E. Gompperb, David Valenzuela-Galvánc, Anna R. Layd, Karen M. Kapheime, Christine Hassf, Susan D. Booth-Binczikg, Gerald A. Binczikh, Ben T. Hirschi, Maureen McColginj, John L. Koprowskik, Katherine McFaddenl,1, Robert K. Waynea, ⁎ Klaus-Peter Koepflim,n, a Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA b School of Natural Resources, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA c Departamento de Ecología Evolutiva, Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Conservación, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Cuernavaca, Morelos 62209, Mexico d Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA e Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322, USA f Wild Mountain Echoes, Vail, AZ 85641, USA g New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY 12233, USA h Amsterdam, New York 12010, USA i Zoology and Ecology, College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD 4811, Australia j Department of Biological Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA k School of Natural Resources and the Environment, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA l College of Agriculture, Forestry and Life Sciences, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29634, USA m Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, Washington, D.C. -

Helogale Parvula)

Vocal Recruitment in Dwarf Mongooses (Helogale parvula) Janneke Rubow Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Faculty of Science at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Michael I. Cherry Co-supervisor: Dr. Lynda L. Sharpe March 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Janneke Rubow, March 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Vocal communication is important in social vertebrates, particularly those for whom dense vegetation obscures visual signals. Vocal signals often convey secondary information to facilitate rapid and appropriate responses. This function is vital in long-distance communication. The long-distance recruitment vocalisations of dwarf mongooses (Helogale parvula) provide an ideal opportunity to study informative cues in acoustic communication. This study examined the information conveyed by two recruitment calls given in snake encounter and isolation contexts, and whether dwarf mongooses are able to respond differently on the basis of these cues. Vocalisations were collected opportunistically from four wild groups of dwarf mongooses. The acoustic parameters of recruitment calls were then analysed for distinction between contexts within recruitment calls in general, distinction within isolation calls between groups, sexes and individuals, and the individuality of recruitment calls in comparison to dwarf mongoose contact calls. -

2021 Fur Harvester Digest 3 SEASON DATES and BAG LIMITS

2021 Michigan Fur Harvester Digest RAP (Report All Poaching): Call or Text (800) 292-7800 Michigan.gov/Trapping Table of Contents Furbearer Management ...................................................................3 Season Dates and Bag Limits ..........................................................4 License Types and Fees ....................................................................6 License Types and Fees by Age .......................................................6 Purchasing a License .......................................................................6 Apprentice & Youth Hunting .............................................................9 Fur Harvester License .....................................................................10 Kill Tags, Registration, and Incidental Catch .................................11 When and Where to Hunt/Trap ...................................................... 14 Hunting Hours and Zone Boundaries .............................................14 Hunting and Trapping on Public Land ............................................18 Safety Zones, Right-of-Ways, Waterways .......................................20 Hunting and Trapping on Private Land ...........................................20 Equipment and Fur Harvester Rules ............................................. 21 Use of Bait When Hunting and Trapping ........................................21 Hunting with Dogs ...........................................................................21 Equipment Regulations ...................................................................22 -

Educator's Guide

Educator’s Guide the jill and lewis bernard family Hall of north american mammals inside: • Suggestions to Help You come prepared • essential questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for teaching in the exhibition • map of the Exhibition • online resources for the Classroom • Correlations to science framework • glossary amnh.org/namammals Essential QUESTIONS Who are — and who were — the North as tundra, winters are cold, long, and dark, the growing season American Mammals? is extremely short, and precipitation is low. In contrast, the abundant precipitation and year-round warmth of tropical All mammals on Earth share a common ancestor and and subtropical forests provide optimal growing conditions represent many millions of years of evolution. Most of those that support the greatest diversity of species worldwide. in this hall arose as distinct species in the relatively recent Florida and Mexico contain some subtropical forest. In the past. Their ancestors reached North America at different boreal forest that covers a huge expanse of the continent’s times. Some entered from the north along the Bering land northern latitudes, winters are dry and severe, summers moist bridge, which was intermittently exposed by low sea levels and short, and temperatures between the two range widely. during the Pleistocene (2,588,000 to 11,700 years ago). Desert and scrublands are dry and generally warm through- These migrants included relatives of New World cats (e.g. out the year, with temperatures that may exceed 100°F and dip sabertooth, jaguar), certain rodents, musk ox, at least two by 30 degrees at night. kinds of elephants (e.g. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

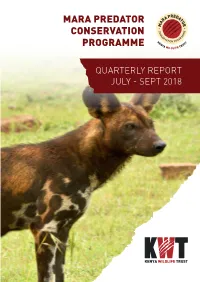

MPCP-Q3-Report-Webversion.Pdf

MARA PREDATOR CONSERVATION PROGRAMME QUARTERLY REPORT JULY - SEPT 2018 MARA PREDATOR CONSERVATION PROGRAMME Q3 REPORT 2018 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY During this quarter we started our second lion & cheetah survey of 2018, making it our 9th consecutive time (2x3 months per year) we conduct such surveys. We have now included Enoonkishu Conservancy to our study area. It is only when repeat surveys are conducted over a longer period of time that we will be able to analyse population trends. The methodology we use to estimate densities, which was originally designed by our scientific associate Dr. Nic Elliot, has been accepted and adopted by the Kenya Wildlife Service and will be used to estimate lion densities at a national level. We have started an African Wild Dog baseline study, which will determine how many active dens we have in the Mara, number of wild dogs using them, their demographics, and hopefully their activity patterns and spatial ecology. A paper detailing the identification of key wildlife areas that fall outside protected areas was recently published. Contributors: Niels Mogensen, Michael Kaelo, Kelvin Koinet, Kosiom Keiwua, Cyrus Kavwele, Dr Irene Amoke, Dominic Sakat. Layout and design: David Mbugua Cover photo: Kelvin Koinet Printed in October 2018 by the Mara Predator Conservation Programme Maasai Mara, Kenya www.marapredatorconservation.org 2 MARA PREDATOR CONSERVATION PROGRAMME Q3 REPORT 2018 MARA PREDATOR CONSERVATION PROGRAMME Q3 REPORT 2018 3 CONTENTS FIELD UPDATES ....................................................... -

Additions to Mammals Killed by Motor Vehicles on Vía Del Escobero, Envigado

Revista EIA, ISSN 1794-1237 / Year XI / Volume 11 / Issue N.22 / July-December 2014 / pp. 137-142 Technical-scientific biannual publication / Escuela de Ingeniería de Antioquia —EIA—, Envigado (Colombia) ADDITIONS TO MAMMALS KILLED BY MOTOR VEHICLES ON VÍA DEL ESCOBERO, ENVIGADO CARLOS A. DELGADO-V. 1 ABSTRACT Vertebrate road kills are a generalized problem around the world, but they are scarcely documented on Colombian highways, especially in peri-urban areas. This study describes the highway mortality of mammals in a six year-period (2008-2013) on Vía del Escobero (Envigado, Antioquia, Colombia). Mammal groups that presented the highest mortality rates were marsupials (54.3%), carnivores (25.7%), and rodents (17.5%). Although there was a lower diversity and fewer individual fatalities than in previous years for the same highway, this study reports a greater number of fatalities for some endangered and unknown species such as Leopardus tigrinus, Puma yag- ouaroundi, and Bassaricyon neblina. This study also added three new species to the road kill list on this highway. KEYWORDS: Road ecology, urban ecology, Medellín, Valle de Aburrá, Valle de San Nicolás ADICIONES AL ATROPELLAMIENTO VEHICULAR DE MAMÍFEROS EN LA VÍA DE EL ESCOBERO, ENVIGADO (ANTIOQUIA), COLOMBIA RESUMEN El atropellamiento vehicular de fauna es un problema generalizado alrededor del Mundo pero escasamente estudiado en las carreteras colombianas, especialmente en áreas periurbanas. Aquí se describe la mortalidad de mamíferos entre los años 2008 a 2013 en la vía El Escobero (Envigado, Antioquia). Los mamíferos más atropella- dos en este periodo fueron los marsupiales (54.3 %), los carnívoros (25.7 %) y los roedores (17.5 %). -

TROUBLE-MAKING BROWN BEAR URSUS ARCTOS LINNAEUS, 1758 (MAMMALIA: CARNIVORA) – Behavioral PATTERN ANALYSIS of the SPECIALIZED INDIVIDUALS

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © 30 Décembre Vol. LIV (2) pp. 541–554 «Grigore Antipa» 2011 DOI: 10.2478/v10191-011-0032-0 TROUBLE-MAKING BROWN BEAR URSUS ARCTOS LINNAEUS, 1758 (MAMMALIA: CARNIVORA) – BEHAVIORal PATTERN ANALYSIS OF THE SPECIALIZED INDIVIDUALS LEONARDO BERECZKY, MIHAI POP, SILVIU CHIRIAC Abstract. In Romania more than 500 damage cases caused by large carnivores are reported by livestock owners and farmers each year. This is the main reason for hunting derogation despite the protected species status. This study is the result of detailed examination of 198 damage cases caused by bears in 2008 and 2009, in the south- eastern Carpathian Mts in Romania. The goal of the study was to examine whether an individual-specific behavioural pattern among problematic bears exists. We looked for bears which showed repeated killing of livestock, a phenomenon claimed by livestock owners to indicate the presence of a problematic individual in the area. In 27% of the observed cases the problematic bears exhibited specific behaviour patterns: clear specialization on a certain type of damage, high degree of tolerance for humans, selectivity for certain prey items, returning back to the damage site in less than 8 days. Fast adaptation and taking advantage of easily obtainable food around human created artificial sources is characteristic for all bear species, due to their high learning capacity and ecological plasticity, but from the conservation and management point of view dealing with individuals which specialize to live mainly around artificial areas becomes a “problem”. Thus defining and identifying individual behaviour patterns oriented towards conflicting behaviour might be useful for wildlife managers in identifying “problem individuals” in order to apply the proper control methods.