Small Predator Impacts on Deer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bobcat LHOTB022604

Life History of the Bobcat LHOTB022604 The bobcat belongs to the family Felidae, which contains mountain lion, Florida panther, ocelot, lynx, jaguar, margay and jaguarundi. Historically the bobcat ranged throughout the lower 48 states and into parts of southern Canada and northern Mexico. Bobcats are found throughout Alabama with greater abundance in the Coastal Plains and Piedmont areas. DESCRIPTION: The bobcat is slightly more than twice the size of a domestic cat. Adult males’ weight ranges between 16-40 pounds and the females between 8-33 pounds. Coloration can vary but generally is yellowish or reddish brown streaked or spotted black or dark brown. The belly and underside of the tail is white. Black spots or bars are found on the belly and inside the forelegs and may extend up the sides to the back. Their tail is short (<5 ¾ inches) with distinct black bars at the tip. REPRODUCTION: Bobcats normally breed once a year from January through March with most births occurring during April and May. After a gestation period of 62 days, a litter of 1-4 kittens is born with 3 kittens being the average litter size. HABITAT: Bobcats are highly adapted to a variety of habitats. They prefer forested habitats with a dense understory and high prey densities. The only habitat type not used is heavily farmed agriculture land. Bobcats are territorial and readily defend their home range. Their home range can vary from 1-80 square miles. Bobcats may use a variety of denning sites such as rock ledges, hollow trees and logs, and brush piles. -

The Red and Gray Fox

The Red and Gray Fox There are five species of foxes found in North America but only two, the red (Vulpes vulpes), And the gray (Urocyon cinereoargentus) live in towns or cities. Fox are canids and close relatives of coyotes, wolves and domestic dogs. Foxes are not large animals, The red fox is the larger of the two typically weighing 7 to 5 pounds, and reaching as much as 3 feet in length (not including the tail, which can be as long as 1 to 1 and a half feet in length). Gray foxes rarely exceed 11 or 12 pounds and are often much smaller. Coloration among fox greatly varies, and it is not always a sure bet that a red colored fox is indeed a “red fox” and a gray colored fox is indeed a “gray fox. The one sure way to tell them apart is the white tip of a red fox’s tail. Gray Fox (Urocyon cinereoargentus) Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) Regardless of which fox both prefer diverse habitats, including fields, woods, shrubby cover, farmland or other. Both species readily adapt to urban and suburban areas. Foxes are primarily nocturnal in urban areas but this is more an accommodation in avoiding other wildlife and humans. Just because you may see it during the day doesn’t necessarily mean it’s sick. Sometimes red fox will exhibit a brazenness that is so overt as to be disarming. A homeowner hanging laundry may watch a fox walk through the yard, going about its business, seemingly oblivious to the human nearby. -

2021 Fur Harvester Digest 3 SEASON DATES and BAG LIMITS

2021 Michigan Fur Harvester Digest RAP (Report All Poaching): Call or Text (800) 292-7800 Michigan.gov/Trapping Table of Contents Furbearer Management ...................................................................3 Season Dates and Bag Limits ..........................................................4 License Types and Fees ....................................................................6 License Types and Fees by Age .......................................................6 Purchasing a License .......................................................................6 Apprentice & Youth Hunting .............................................................9 Fur Harvester License .....................................................................10 Kill Tags, Registration, and Incidental Catch .................................11 When and Where to Hunt/Trap ...................................................... 14 Hunting Hours and Zone Boundaries .............................................14 Hunting and Trapping on Public Land ............................................18 Safety Zones, Right-of-Ways, Waterways .......................................20 Hunting and Trapping on Private Land ...........................................20 Equipment and Fur Harvester Rules ............................................. 21 Use of Bait When Hunting and Trapping ........................................21 Hunting with Dogs ...........................................................................21 Equipment Regulations ...................................................................22 -

Vulpes Vulpes) Evolved Throughout History?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Environmental Studies Undergraduate Student Theses Environmental Studies Program 2020 TO WHAT EXTENT HAS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMANS AND RED FOXES (VULPES VULPES) EVOLVED THROUGHOUT HISTORY? Abigail Misfeldt University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/envstudtheses Part of the Environmental Education Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Disclaimer: The following thesis was produced in the Environmental Studies Program as a student senior capstone project. Misfeldt, Abigail, "TO WHAT EXTENT HAS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMANS AND RED FOXES (VULPES VULPES) EVOLVED THROUGHOUT HISTORY?" (2020). Environmental Studies Undergraduate Student Theses. 283. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/envstudtheses/283 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Environmental Studies Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Studies Undergraduate Student Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TO WHAT EXTENT HAS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMANS AND RED FOXES (VULPES VULPES) EVOLVED THROUGHOUT HISTORY? By Abigail Misfeldt A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The University of Nebraska-Lincoln In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Science Major: Environmental Studies Under the Supervision of Dr. David Gosselin Lincoln, Nebraska November 2020 Abstract Red foxes are one of the few creatures able to adapt to living alongside humans as we have evolved. All humans and wildlife have some id of relationship, be it a friendly one or one of mutual hatred, or simply a neutral one. Through a systematic research review of legends, books, and journal articles, I mapped how humans and foxes have evolved together. -

Bobcat Rank Activity Plans for Parents + Leaders

Bobcat Rank Activity Plans for Parents + Leaders Here are two Den Adventure Plans to use as “First Activities” for your Den when you start up a new Program Year (at a Den Meeting or fun event) … … to learn and earn (or review) the Bobcat Rank Share with attending parents … get their help! From the Den Leader Guides: The Bobcat rank is the first badge awarded a new Cub Scout (2018: except Lions). As a new member, a scout may work on the Bobcat rank requirements while simultaneously working on the next rank as well. A scout cannot receive the Tiger, Wolf, Bear, Webelos, or Arrow of Light badge until the scout has completed Bobcat requirements and earned the Bobcat badge. Scouts can normally earn their Bobcat badge well within the first month of becoming a new Cub Scout (2018: except Lions). Here’s how you can help! Practice the requirements with your scout and the other scouts at a den activity, and encourage them to work on the requirements with their families also. Requirement 7 is a home-based requirement. The requirements are found in each of the youth handbooks as well as listed below: Bobcat Requirements: 1. Learn and say the Scout Oath, with help if needed. 2. Learn and say the Scout Law, with help if needed. 3. Show the Cub Scout sign. Tell what it means. 4. Show the Cub Scout handshake. Tell what it means. 5. Say the Cub Scout motto. Tell what it means. 6. Show the Cub Scout salute. Tell what it means. 7. -

Furbearers Complaint

Kristine Akland Akland Law Firm, PLLC 317 E. Spruce Street P.O. Box 7274 Missoula, MT 59807 (406) 544-9863 [email protected] Tanya Sanerib, pro hac vice admission pending Center for Biological Diversity 2400 NW 80th Street, #146 Seattle, WA 98117 (206) 379-7363 [email protected] Sarah Uhlemann, pro hac vice admission pending Center for Biological Diversity 2400 NW 80th Street, #146 Seattle, WA 98117 (206) 327-2344 [email protected] Attorneys for Plaintiff IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MONTANA MISSOULA DIVISION CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL Case No.: DIVERSITY, Plaintiff, COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF vs. UNITED STATES FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE; and RYAN ZINKE, in his official capacity as Secretary of the Interior. Defendants. INTRODUCTION 1. Each year around 80,000 wild bobcats, river otters, gray wolves, Canada lynx, and brown bears are killed and commercially exported from the United States to supply the international fur trade. 2. Commercial trapping of these “furbearer” species can cause population declines at the local, state, regional, and even national levels and significantly impact the ecosystems of which these species are a critical component. In fact, scientists have expressed serious concerns regarding the sustainability of trapping and harvest of these five furbearer species in many areas throughout the United States. 3. Bobcats, river otters, gray wolves, Canada lynx, and brown bears are protected as Appendix II species under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (“CITES”). CITES, March 3, 1973, 27 U.S.T. 1087, 993 U.N.T.S. 243 (entered into force July 1, 1975). -

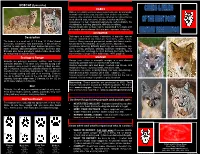

Canids & Felids of the West Point

BOBCAT (Lynx rufus) DISEASE RABIES Rabies is a viral central nervous system disease in mammals, transmitted in saliva, usu. by a bite from an infected animal. Vectors: Any mammal can become infected /w rabies but its most often in bats, raccoons, skunks, coyotes and foxes. Symptoms: no fear, hyperaggressiveness, self-mutilation. No coordination, drooling, paralysis, difficulty breathing. Human health risk: serious; can be transmitted to humans and pets and is almost always fatal w/o post-exposure treatment. Photo Credit: Don Henderson Photo Credit: Ken Canning DISTEMPER Description Distemper is a viral nervous, respiratory, & digestive system disease transmitted via nose/eye secretions, urine, feces. The bobcat is a small cat (2-3 ft long, 10-30 lbs.) found Vectors: Many mammal groups incl canids (incl foxes) muste- in forests, mountains, and brushlands. It has brown to lids (weasels and skunks), raccoons, bears, and others. buff fur /w dark spots. Its short bobbed tail gives it the Symptoms: drooling, difficulty breathing, jaw movements, sei- name “bobcat” and distinguishes it from domestic cats. zures, circling, paralysis, wasting, foot/nose hardening. Hu- Bobcats also have prominent sideburn-like cheek tufts. man health risk: unknown to infect humans, but highly fatal to Its eartips and tail tips are black. non-vaccinated dogs (~50% adult dogs, ~80% puppies) Ecology & Range MANGE Bobcats are primarily nocturnal, solitary, and fiercely Mange (usu. refers to sarcoptic mange) is a skin disease territorial animals. They often only interact during mat- caused by parasitic mites in non-human mammals. ing season, once a year in early spring. Litters are usu- Vectors: domestic cats and dogs, livestock esp sheep, wild ally 1-3 kittens. -

Coyote Valley Bobcat Habitat Preference and Connectivity Report Prepared by Laurel E.K

COYOTE VALLEY BOBCAT HABITAT PREFERENCE AND CONNECTIVITY REPORT PREPARED BY LAUREL E.K. SERIEYS, Ph.D., and CHRISTOPHER WILMERS, Ph.D. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ PREPARED FOR PENINSULA OPEN SPACE TRUST SANTA CLARA VALLEY OPEN SPACE AUTHORITY JUNE 2019 AUTHORS Laurel E.K. Serieys, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Fellow Christopher Wilmers*, Ph.D., Associate Professor Environmental Studies Department University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) Santa Cruz, California, USA *Corresponding author at University of California, Santa Cruz E-mail address: [email protected] TECHNICAL REPORT PREPARED FOR Peninsula Open Space Trust and Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority June 30, 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank the following individuals for their work that ensured the success of this study: Neal Sharma, Peninsula Open Space Trust Galli Basson, Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority Stephani Matsushima, Environmental Studies Department, UCSC Tanya Diamond and Ahiga Snyder, Pathways for Wildlife Matthew S. Rogan, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Cape Town, South Africa Barry Nichols, Ph.D. Candidate, Center for Integrated Spatial Research, UCSC Justin Suraci, Ph.D., Environmental Studies Department, UCSC Mercer Lawing, Caging Bobcats, Barstow, California Shawn Lockwood, Santa Clara Valley Water District Staff at Santa Clara County Parks FUNDING We would like to thank the following funders for supporting this study: Moore Foundation Peninsula Open Space Trust California Department of Fish and Wildlife Santa Clara Valley Habitat Agency Santa -

Tribal Wildlife Grant Final Report Makah Cougar and Bobcat Research Grant: F12AP00260

Tribal Wildlife Grant Final Report Makah Cougar and Bobcat Research Grant: F12AP00260 Prepared by: Shannon Murphie and Rob McCoy 1 INTRODUCTION Mountain lions or cougars (Puma concolor) and bobcats (Lynx rufus) are both native mammals of the family Felidae. Mountain lions are large solitary cats with the greatest range of any large wild terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere (Iriarte et al. 1990). Bobcats are also solitary cats that range from southern Canada to northern Mexico, including most of the continental United States. Both species are predators and as such play a prominent role in Native American mythology and culture due to their perceived attributes such as grace, strength, eyesight, and hunting ability. Similar to other Native American Tribes, predators have played a key role in the culture and ceremonies of the Makah people. Gray wolves (Canis lupus), black bear (Ursus americanus), cougars, and bobcats all are important components of Makah culture both historically and in contemporary times. For example, black bears and gray wolves both represented important clans in Makah history. Gray wolves exhibited cooperative behavior that provided guidelines for human behavior and “Klukwalle,” or wolf ritual, was a secret society that required a 6 day initiation period (G. Arnold, personal communication). Wolf hides were also used in dance and costume regalia. Bear hides were worn by men of status (Chapman 1994) and as regalia during whale hunts (G. Ray, personal communication). Cougars and bobcats play a smaller, but still important role in Makah history and contemporary culture. During naming ceremonies a Makah name is given which best reflects an individual, often an animal such as the mountain lion is used as it represents intelligence and power. -

OREGON FURBEARER TRAPPING and HUNTING REGULATIONS

OREGON FURBEARER TRAPPING and HUNTING REGULATIONS July 1, 2020 through June 30, 2022 Please Note: Major changes are underlined throughout this synopsis. License Requirements Trapper Education Requirement By action of the 1985 Oregon Legislature, all trappers born after June 30, Juveniles younger than 12 years of age are not required to purchase a 1968, and all first-time Oregon trappers of any age are required to license, except to hunt or trap bobcat and river otter. However, they must complete an approved trapper education course. register to receive a brand number through the Salem ODFW office. To trap bobcat or river otter, juveniles must complete the trapper education The study guide may be completed at home. Testing will take place at course. Juveniles 17 and younger must have completed hunter education Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) offices throughout the to obtain a furtaker’s license. state. A furtaker’s license will be issued by the Salem ODFW Headquarters office after the test has been successfully completed and Landowners must obtain either a furtaker’s license, a hunting license for mailed to Salem headquarters, and the license application with payment furbearers, or a free license to take furbearers on land they own and on has been received. Course materials are available by writing or which they reside. To receive the free license and brand number, the telephoning Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, I&E Division, 4034 landowner must obtain from the Salem ODFW Headquarters office, a Fairview Industrial Drive SE, Salem, OR 97302, (800) 720-6339 x76002. receipt of registration for the location of such land prior to hunting or trapping furbearing mammals on that land. -

Red & Gray Foxes

Red & Gray Foxes Valerie Elliott The gray fox and red fox are members of the Canidae biological family, which puts them in the same family as domestic dogs, wolves, jackals and coyotes. The red fox is termed “Vulpes vulpes” in Latin for the genus and species. The gray fox is termed “Urocyon cinereoargenteus”. Gray foxes are sometimes mistaken to be red foxes but red foxes are slimmer, have longer legs and larger feet and have slit-shaped eyes. Gray foxes have oval shaped pupils. The gray fox is somewhat stout and has shorter legs than the red fox. The tail has a distinct black stripe along the top and a black tip. The belly, chest, legs and sides of the face are reddish-brown. Red foxes have a slender body, long legs, a slim muzzle, and upright triangular ears. They vary in color from bright red to rusty or reddish brown. Their lower legs and feet have black fur. The tail is a bushy red and black color with a white tip. The underside of the red fox is white. They are fast runners and can reach speeds of up to 30 miles per hour. They can leap more than 6 feet high. Red and gray foxes primarily eat small rodents, birds, insects, nuts and fruits. Gray foxes typically live in dense forests with some edge habitat for hunting. Their home ranges typically are 2-4 miles. Gray foxes can also be found in suburban areas. Ideal red fox habitat includes a mix of open fields, small woodlots and wetlands – making modern-day Maryland an excellent place for it to live. -

Super Senses

Young Naturalist These Dogs Are Wild Minnesota’s wolves, coyotes, and foxes are very good dogs in their own special ways. By Mary Hoff FROM PUGS TO POODLES, from great Danes to golden retrievers—the dogs that live with people come in many types and sizes. Did you know that all of them are related to wild dogs? Pet dogs, wolves, foxes, and coyotes are all members of Canidae, the dog family. This family includes nearly three dozen species that live in the wild on every continent except Antarctica. Four of these species live in Minnesota: the gray wolf, the coyote, the red fox, and the gray fox. These animals share many traits with their domestic relatives—but they have some surprising differences too. Let’s take a look at how the dogs that share our homes compare with their wild cousins. Super Senses You’ve probably heard that dogs can hear sounds too high for people to hear. Members of the canid family are known for their excellent senses of hearing and smell. These senses help them find prey in the wild. They also help them learn about their world and each other. Canids can’t talk, but they still communicate. Doglike mammals rely on sound and smell to share secret (to us) messages with each other. You may have heard of dogs being used to find lost people or search for pollution, weapons, or illegal drugs using their sense of smell. Inside their long snouts, elaborate bone structures and lots of nerves give them a super sense of smell.