The Institutionalized Stratification of the Chinese Higher Education System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Higher Education Reform 1998-2003: a Summary

Asia Pacific Education Review Copyright 2004 by Education Research Institute 2004, Vol. 5, No. 1, 14-22. China’s Higher Education Reform 1998-2003: A Summary Li Lixu Shandong Normal University, P. R. China Profoundly important and unprecedented changes have taken place in China’s higher education since 1998, when Zhu Rongji Administration (1998-2003) decided to carry out a new round of educational reform. These changes include some breakthroughs in macro administrative system reform, growth in the total amount of educational expenditure, the enlargement of the recruitment scale of higher education, and positive changes in personnel, reward distribution and rear service reforms. The purpose of this paper is to offer a summary of these reforms. It discusses (1) the internal reasons for the reforms, (2) the main events and measures, (3) the main contents and achievements, (4) and the main problems of these reforms. Key Words: China, higher education, reform 1The system and model of Chinai’s higher education was In 1999, among all the employed of China, graduates of basically formed in the 1950’s and 1960’s in imitation of the two-year higher education and over only amounted to 3.8% of higher educational system and model of the former U.S.S.R. the total; that of senior middle school, 11.9%; that of junior in the 1950’s (Li, 2001). Thereafter, even up to the late middle school, 39.9%; that of primary school, 33.3%; and 1990’s, China’s higher education showed no tremendous those workers who were illiterate even amounted to 11.0% reforms or great changes in spite of some “minor operations.” (National Center for Education Development Research But, since 1998, when China faced the challenges of the [NCEDR], 2001, p. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

Chinese Academic Library Services: a Web Survey

ISSN: 2474-3542 Journal homepage: http://journal.calaijol.org Chinese Academic Library Services: A Web Survey Guoying Liu Abstract: Chinese students form a significant population on Canadian university campuses. Literature indicates that these students face various challenges when using library services to meet their information needs. Canadian academic libraries need to better understand this group’s previous library experiences in China to help them address these challenges. A survey was conducted on the main library websites of all thirty-nine Chinese universities of the Project 985, a project initiated by Chinese government to found world class universities in China. It reveals that certain services reported as challenges for Chinese students by previous studies, such as: interlibrary loan, document delivery, reference services, and library instructions are popular in Chinese academic libraries; however, subject services, data services, and some other services are not as well established compared to their counterparts in Canada. To cite this article: Liu, G. (2016). Chinese academic library services: a web survey. International Journal of Librarianship, 1(1), 38-54. https://doi.org/10.23974/ijol.2016.vol1.1.14 To submit your article to this journal: Go to http://ojs.calaijol.org/index.php/ijol/about/submissions INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LIBRARIANSHIP, 1(1), 38-54 ISSN:2474-3542 Chinese Academic Library Services: A Web Survey Guoying Liu Leddy Library, University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada ABSTRACT Chinese students form a significant population on Canadian university campuses. Literature indicates that these students face various challenges when using library services to meet their information needs. Canadian academic libraries need to better understand this group’s previous library experiences in China to help them address these challenges. -

Tibet School Music Education Development Process Since the Founding of New China

2019 2nd International Workshop on Advances in Social Sciences (IWASS 2019) Tibet School Music Education Development Process since the Founding of New China Kun Yang Lhasa Normal College, Lhasa, 850000, China, Tibet University, Lhasa, 850000, China Keywords: Tibet, Music education, The development course Abstract: music education in Tibet school is an important part of Tibet school education. With the national policy, social consciousness, teaching units, families and individuals attach importance to and help music education in schools, the public pays more and more attention to the importance of music education in schools. This paper reviews and summarizes the development of music education in preschool, primary and secondary schools and higher music education in Tibet since the founding of new China, and comprehensively grasizes the past and present of music education in Tibet schools, so as to provide reference for the sustainable development of music education in Tibet schools. 1. Introduction Since the founding of the People's Republic of China, music education in Tibet schools has developed in three aspects: preschool music education in Tibet, music education in Tibet primary and secondary schools, and music education in Tibet higher education. The higher music education in Tibet is divided into three parts: music education in Tibet (music major), music education in Tibet (preschool education major) and music education in Tibet (public art). By reviewing and tracing the development process of music education components in Tibet schools, it is of great theoretical and practical significance to help absorb advanced teaching experience and realize leapfrog development in the future. 2. Tibet Preschool Music Education Preschool education in Tibet can be divided into two periods: pre-democratic reform preschool education (before March 1959) and post-democratic reform preschool education (after March 1959). -

1 the Hohenheim-Xi'an Jiaotong Research Seminar in Theoretical

The Hohenheim-Xi'an Jiaotong Research Seminar in Theoretical and Empirical Economics Xi'an Jiaotong University School of Economics and Finance March 2-6, 2020 Xi’an, China Organizing Committee: Prof. Zao Sun, Xi’an Jiaotong University, China Prof. Peng Nie, Xi’an Jiaotong University, China Prof. Klaus Prettner, University of Hohenheim, Germany Prof. Alfonso Sousa-Poza, University of Hohenheim, Germany The Faculty of Business, Economics and Social Sciences of the University of Hohenheim and the School of Economics and Finance at the Xi'an Jiaotong University recently signed a memorandum of understanding in order to foster cooperation in all fields of academic life. The aim of this research seminar is to bring together young academics from the University of Hohenheim and Xi'an Jiaotong University (as well as a selection of Chinese universities) to present their research and promote research cooperation. Submissions from all fields of economics are welcome, and they can be empirical or theoretical in nature. This seminar also forms part of the PhD programme at the University of Hohenheim (course “Doctoral Seminar”). Date and venue The workshop will take place between March 2-6, 2020 at the School of Economics and Finance, Xi'an Jiaotong University in Xi’an, China. Submission All doctoral students as well as young post-doctoral researchers are invited to submit a full paper or a 1-page extended abstract by August 30, 2019 to Peng Nie ([email protected]), Klaus Prettner ([email protected]) and Alfonso Sousa-Poza (alfonso.sousa-poza@uni- hohenheim.de). The authors of accepted abstracts will be notified by mid-September and completed draft papers will then be expected by January 31, 2020. -

Nanjing University of Aeronautics & Astronautics

iao.nuaa.edu.cn | ciee.nuaa.edu.cn | studyatnuaa nuaa.official NANJING UNIVERSITY OF AERONAUTICS & ASTRONAUTICS INTERNATIONAL PROSPECTUS 2020 CONTENTS Welcome to NUAA 03 NUAA at a Glance 04 Leading Researches 06 Teaching and Experiment Facilities 07 Fostering University- Enterprise Cooperation 08 Global Programs 09 Our Current Student 10 What our Alumni Say? 11 Undergraduate Programs 12 Postgraduate Programs 16 Chinese Language Program 18 Foundation Program 19 Admission 20 Tuition Fees & Expenses 22 Scholarships 24 International Student Support 25 Vibrant Student Life 26 Sports & Recreation 27 Students Activities 28 Accommodation 30 Dining 31 Nanjing City 32 10 Things To Do in Nanjing 34 WELCOME TO NUAA Nanjing University of Aeronautics and one of the 55 universities with graduate school Astronautics (NUAA) is one of China’s premier in China. NUAA has also been listed under the learning and research institutions. NUAA has “National Project 211” universities. developed into a comprehensive, research based university that excels in many aspects At NUAA you will find an international community of engineering (particularly in Aeronautics, of learners and researchers in the city of Nanjing Astronautics and Mechanical Engineering) on China’s east coast. We were one of the first sciences, Economics and Management and universities in China to offer Engineering and many others. Business programs taught in English medium. Our graduates use their NUAA education all over NUAA is among the first batch of national the world: in the air, in space and -

Eastern Coastal Region, Family and Individual in Higher

HIGHER EDUCATION CHOICES AND DECISION-MAKING A Narrative Study of Lived Experiences of Chinese International Students and Their Parents Vivienne jing Zhang A thesis submitted to AUT University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) April 2013 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TTITLE PAGE ........................................................................................................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................... ii LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................... ……. iviii ATTESTATION OF AUTHORSHIP ........................................................................................ x ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................... ix ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................. ixi CHAPTER 1 SETTING THE SCENE ...................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Some Observations on Recent Trends in Chinese International Students Choosing to Study Abroad.......................................................................................................................... 1 -

From Carp to Dragon the Shanghai List and the Neoliberal Pursuit of Modernization in Chinese Higher Education

From Carp to Dragon The Shanghai List and the Neoliberal Pursuit of Modernization in Chinese Higher Education Jeremy Cohen School of International Service: B.A. International Studies College of Arts and Sciences: B.S. Economics University Honors Advisor: Dr. James H. Mittelman School of International Service Spring 2012 2 FROM CARP TO DRAGON: THE SHANGHAI LIST AND THE NEOLIBERAL PURSUIT OF MODERNIZATION IN CHINESE HIGHER EDUCATION Do global university rankings reflect an assimilation of widely held transnational views about education or are these rankings the product of historically and culturally contingent national experience? This study examines how the emergence of the first global ranking—the Shanghai Jiao Tong University Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU)—reflects the intermingling of dominant global discourses about higher education with Chinese realities and asks what role ARWU has played in the restructuring of power and knowledge in Chinese higher education under conditions of globalization. A number of methods are employed—including the historical contextualization of ARWU, a critical review of its methodology, and interviews with Chinese students and scholars. The analysis demonstrates that ARWU is both a product and an instrument of neoliberalism in the Chinese context. Allied to a specific discourse of excellence and quality in higher education, it reproduces the national narrative of modernization that is the hallmark of Chinese neoliberalism. ARWU also builds legitimacy for policies that restructure higher education -

Westlake Youth Forum 2019 第四届西湖青年论坛

Westlake Youth Forum 2019 第四届西湖青年论坛 Call for Application Zhejiang University and China Medical Board (CMB) joint hands to host the 4th Westlake Youth Forum in 2019, with facilitation from China Health Policy and Management Society (CHPAMS). The Organizing Committee of the Forum is pleased to invite applications for participating in the Forum. The Forum provides a platform for young scholars worldwide to build up academic network, to exchange scientific thoughts and research experience, to communicate with senior scholars and policymakers, and to advance health policy in China. The 2019 Forum will be a three-day event for young researchers and practitioners in health policy and system on June 10-13, 2019 at Zhejiang University, China. Westlake Youth Forum: • When: June 10-13, 2019 • Where: Zhejiang University International Campus, Haining, Zhejiang Province, China • Preliminary Program: June 10. Registration and social activities June 11-12. Academic sessions and events of the Westlake Youth Forum June 13. Field visit What will be provided to all participants: • Local expenses including meals, accommodation, and local transportation in Haining, Zhejiang; • Networking with world-class academic leaders and young scholars from inside and outside of China; • Networking with Chinese academic leaders to explore your career opportunities in China; • Presenting your research and communicating with academic leaders and peers at the Forum. Who can apply for the participation (Eligibility)? • Scholars under 45 years old from CMB OC eligible schools (see Appendix I), OC awardees preferred but not required; • Working in public health related fields; • Having the interest to build collaboration with academic and research institutions, governmental departments, and corporations in China. -

China Education Hotels / Leisure / Initiation of Coverage

Deutsche Bank Markets Research Asia Industry Date China 4 January 2018 Consumer China Education Hotels / Leisure / Initiation of Coverage Gaming Tallan Zhou Karen Tang Research Analyst Research Analyst Bright future (+852 ) 2203 6464 (+852 ) 2203 6141 [email protected] [email protected] K12 after-school tutoring is a secular growth sector Top picks We analyze the supply/demand condition of China's K12 after-school tutoring New Oriental (EDU.N),USD101.57 Buy market and conclude the sector will likely see secular growth in the next five TAL Education (TAL.N),USD29.71 Buy years. We believe positive demographic growth, an increased number of Source: Deutsche Bank wealthy families, and greater education awareness are the demand drivers. However, China's supply of top universities is still insufficient and the Companies Featured admission rate remains low. This has led to surging needs for after-school tutoring services. We forecast the K12 tutoring market to see a 13-14% CAGR New Oriental (EDU.N),USD101.57 Buy in 2017-22E, assuming: 1) K12 students see a CAGR of 3%, 2) tutoring 2017A 2018E 2019E penetration rate climbs 2.5% p.a.; and 3) ASP rises (like-for-like basis) 5% p.a. P/E (x) 26.3 42.0 33.6 EV/EBITDA (x) 17.0 33.6 25.3 More demand for education in the long term Price/book (x) 6.7 7.8 6.4 China’s Gaokao (college entrance exam)-takers as a percentage of the newborn population increased to 65% in 2016 from only 25% in 2002, while TAL Education (TAL.N),USD29.71 Buy the birth rate remained unchanged at 0.11-0.12%. -

China's Quest for World-Class Universities

MARCHING TOWARD HARVARD: CHINA’S QUEST FOR WORLD-CLASS UNIVERSITIES A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies By Linda S. Heaney, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. April 19, 2111 MARCHING TOWARD HARVARD: CHINA’S QUEST FOR WORLD-CLASS UNIVERSITIES Linda S. Heaney, B.A. MALS Mentor: Michael C. Wall, Ph.D. ABSTRACT China, with its long history of using education to serve the nation, has committed significant financial and human resources to building world-class universities in order to strengthen the nation’s development, steer the economy towards innovation, and gain the prestige that comes with highly ranked academic institutions. The key economic shift from “Made in China” to “Created by China” hinges on having world-class universities and prompts China’s latest intentional and pragmatic step in using higher education to serve its economic interests. This thesis analyzes China’s potential for reaching its goal of establishing world-class universities by 2020. It addresses the specific challenges presented by lack of autonomy and academic freedom, pressures on faculty, the systemic problems of plagiarism, favoritism, and corruption as well as the cultural contradictions caused by importing ideas and techniques from the West. The foundation of the paper is a narrative about the traditional intertwining role of government and academia in China’s history, the major educational transitions and reforms of the 20th century, and the essential ingredients of a world-class institution. -

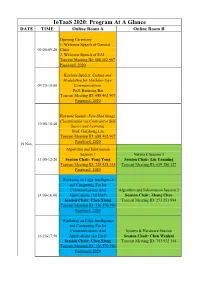

Iotaas 2020: Program at a Glance DATE TIME Online Room a Online Room B

IoTaaS 2020: Program At A Glance DATE TIME Online Room A Online Room B Opening Ceremony 1. Welcome Speech of General 09:00-09:20 Chair 2. Welcome Speech of EAI Tencent Meeting ID: 688 462 967 Password: 2020 Keynote Speech: Coding and Modulation for Machine-Type 09:20-10:00 Communications Prof. Baoming Bai Tencent Meeting ID: 688 462 967 Password: 2020 Keynote Speech: Few-Shot Image Classification via Contrastive Self- 10:00-10:40 Supervised Learning Prof. Guizhong Liu Tencent Meeting ID: 688 462 967 Password: 2020 19 Nov. Algorithm and Information Session 1 Network Session 1 11:00-12:20 Session Chair: Fang Yong Session Chair: Liu Yanming Tencent Meeting ID: 725 528 335 Tencent Meeting ID: 639 386 127 Password: 2020 Workshop on Edge Intelligence and Computing For Iot Communications And Algorithm and Information Session 2 14:00-16:00 Applications (1st Harf) Session Chair: Zhang Chen Session Chair: Chen Xiang Tencent Meeting ID: 273 251 994 Tencent Meeting ID: 156 570 396 Password: 2020 Workshop on Edge Intelligence and Computing For Iot Communications And System & Hardware Session 16:10-17:50 Applications (2st Harf) Session Chair: Chen Wenhui Session Chair: Chen Xiang Tencent Meeting ID: 751 932 354 Tencent Meeting ID: 156 570 396 Password: 2020 Workshop on Satellite Application Session Communications Session Chair: Abdullah Ghaleb 09:00-10:20 and Spatial Information Network Tencent Meeting ID: 672 146 720 Session Chair: Li Jingling Password: 2020 Tencent Meeting ID: 239 301 133 Network Session 2 Artificial Intelligence Session Session Chair: Li Bo Session Chair: Zhang Jingya 10:30-11:50 Tencent Meeting ID: 515 118 859 Tencent Meeting ID: 922 725 202 Password: 2020 Password: 2020 20 Nov.