Relations of the Sufis with the Rulers of Deccan (14^" -17^" Centuries)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5.4 Southern Kingdoms and the Delhi Sultanate

Political Formations UNIT 5 DECCAN KINGDOMS* Structure 5.0 Objectives 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Geographical Setting of the Deccan 5.3 The Four Kingdoms 5.3.1 The Yadavas and the Kakatiyas 5.3.2 The Pandyas and the Hoysalas 5.3.3 Conflict Between the Four Kingdoms 5.4 Southern Kingdoms and the Delhi Sultanate 5.4.1 First Phase: Alauddin Khalji’s Invasion of South 5.4.2 Second Phase 5.5 Administration and Economy 5.5.1 Administration 5.5.2 Economy 5.6 Rise of Independent Kingdoms 5.7 Rise of the Bahmani Power 5.8 Conquest and Consolidation of the Bahmani Power 5.8.1 First Phase: 1347-1422 5.8.2 Second Phase: 1422-1538 5.9 Conflict Between the Afaqis and the Dakhnis and their Relations with the King 5.10 Central and Provincial Administration under the Bahmani Kingdom 5.11 Army Organization under the Bahmani Kingdom 5.12 Economy 5.13 Society and Culture 5.14 Summary 5.15 Keywords 5.16 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 5.17 Suggested Readings 5.18 Instructional Video Recommendations 5.0 OBJECTIVES After going through this Unit, you should be able to: * Prof. Ahmad Raza Khan and Prof. Abha Singh, School of Social Sciences, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi. The present Unit is taken from IGNOU Course 110 EHI-03: India: From 8th to 15th Century, Block 7, Units 26 & 28. • assess the geographical influences on the polity and economy of the Deccan, Deccan Kingdoms • understand the political set-up in South India, • examine the conflicts among the Southern kingdoms, • evaluate the relations of the Southern kingdoms with the Delhi Sultanate, • know their administration and economy, • understand the emergence of new independent kingdoms in the South, • appraise the political formation and its nature in Deccan and South India, • understand the emergence of the Bahmani kingdom, • analyze the conflict between the old Dakhni nobility and the newcomers (the Afaqis) and how it ultimately led to the decline of the Bahmani Sultanate, and • evaluate the administrative structure under the Bahmanis. -

Chapter VI Conclusions

Chapter VI Conclusions Trade and commerce of Adil Shahi Sultanate was gradually increasing through various stages, but it reached to a height after the fall of Barid Shahi and Vijaynagar. The establishment of Bahmani rule had removed Bijapur’s status as a remote frontier post, however, under the Bahamanis Bijapur never possessed the economic or political importance of Gulbarga and Bidar, the two Bahmani capitals. Bijapur’s de facto independence (1490), from Bahmani authority could not suddenly transform the city into a notable centre of Islamic civilization. One political city had to fall or decline so that a new political city rose and grew in its stead. Bidar was declined in the last quarter of 15th century and Vijaynagar was destroyed by confederate Muslim states of the Deccan in the battle of Talikota in 1565 and on its ashes raised the glory of Bijapur. By the end of sixteenth century Bijapur had emerged as one of the major Islamic urban centres. The early seventeenth century saw the peak growth of the city’s population, on the basis of the estimation of James Campbell, two million of population was resided within and outside of fort of Bijapur. Under the aegis of Ibrahim II and Muhammad Adil Shah, Bijapur’s significance in all respects grew further and it became an important city of the Deccan. Migration of Qadiri Sufis into the Bijapur during this period could be seen as an important indicator of urbanization. After the fall of Vijaynagar the resources of sultanate increases and Karwar, Honawar and Bhatkal came in their possession which helps to boost up their trade and 548 J.D.B., Gribble, History of the Deccan, op. -

Nimatullahi Sufism and Deccan Bahmani Sultanate

Volume : 4 | Issue : 6 | June 2015 ISSN - 2250-1991 Research Paper Commerce Nimatullahi Sufism and Deccan Bahmani Sultanate Seyed Mohammad Ph.D. in Sufism and Islamic Mysticism University of Religions and Hadi Torabi Denominations, Qom, Iran The presentresearch paper is aimed to determine the relationship between the Nimatullahi Shiite Sufi dervishes and Bahmani Shiite Sultanate of Deccan which undoubtedly is one of the key factors help to explain the spread of Sufism followed by growth of Shi’ism in South India and in Indian sub-continent. This relationship wasmutual andin addition to Sufism, the Bahmani Sultanate has also benefited from it. Furthermore, the researcher made effortto determine and to discuss the influential factors on this relation and its fruitful results. Moreover, a brief reference to the history of Muslims in India which ABSTRACT seems necessary is presented. KEYWORDS Nimatullahi Sufism, Deccan Bahmani Sultanate, Shiite Muslim, India Introduction: are attributable the presence of Iranian Ascetics in Kalkot and Islamic culture has entered in two ways and in different eras Kollam Ports. (Battuta 575) However, one of the major and in the Indian subcontinent. One of them was the gradual ar- important factors that influence the development of Sufism in rival of the Muslims aroundeighth century in the region and the subcontinent was the Shiite rule of Bahmani Sultanate in perhaps the Muslim merchants came from southern and west- Deccan which is discussed briefly in this research paper. ern Coast of Malabar and Cambaya Bay in India who spread Islamic culture in Gujarat and the Deccan regions and they can Discussion: be considered asthe pioneers of this movement. -

Unit 9 the Deccan States and the Mugmals

I UNIT 9 THE DECCAN STATES AND THE MUGMALS Structure 9.0 Objectives I 9.1 Iiltroduction 9.2 Akbar and the Deccan States 9.3 Jahangir and the Deccan States 9.4 Shah Jahan and the Deccaa States 9.5 Aurangzeb and the Deccan States 9.6 An Assessnent of the Mughzl Policy in tie Deccan 9.7 Let Us Sum Up 9.8 Key Words t 9.9 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises -- -- 9.0 OBJECTIVES The relations between the Deccan states and the Mughals have been discussed in the present Unit. This Unit would introduce you to: 9 the policy pursued by different Mughal Emperors towards the Deccan states; 9 the factors that determined the Deccan policy of the Mughals, and the ultimate outcome of the struggle between the Mughals and the Deccan states. - 9.1 INTRODUCTION - In Unit 8 of this Block you have learnt how the independent Sultanates of Ahmednagar, Bijapur, Golkonda, Berar and Bidar had been established in the Deccan. We have already discussed the development of these states and their relations to each other (Unit 8). Here our focus would be on the Mughal relations with the Deccan states. The Deccan policy of the Mughals was not determined by any single factor. The strategic importance of the Decen states and the administrative and economic necessity of the Mughal empire largely guided the attitude of the Mughal rulers towards the Deccan states. Babar, the first Mughal ruler, could not establish any contact with Deccan because of his pre-occupations in the North. Still, his conquest of Chanderi in 1528 had brought the Mugllal empire close to the northern cbnfines of Malwa. -

List of Entries

List of Entries A Ahmad Raza Khan Barelvi 9th Month of Lunar Calendar Aḥmadābād ‘Abd al-Qadir Bada’uni Ahmedabad ‘Abd’l-RaḥīmKhān-i-Khānān Aibak (Aybeg), Quṭb al-Dīn Abd al-Rahim Aibek Abdul Aleem Akbar Abdul Qadir Badauni Akbar I Abdur Rahim Akbar the Great Abdurrahim Al Hidaya Abū al-Faḍl ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Ḥusayn (Ghūrid) Abū al-Faḍl ‘Allāmī ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Khaljī Abū al-Faḍl al-Bayhaqī ʿAlāʾ al-DīnMuḥammad Shāh Khaljī Abū al-Faḍl ibn Mubarak ‘Alā’ ud-Dīn Ḥusain Abu al-Fath Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar ʿAlāʾ ud-Dīn Khiljī Abū al-KalāmAzād AlBeruni Abū al-Mughīth al-Ḥusayn ibn Manṣūr al-Ḥallāj Al-Beruni Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar al-Suhrawardī AlBiruni Abu’l Fazl Al-Biruni Abu’l Fazl ‘Allāmī Alfī Movements Abu’l Fazl ibn Mubarak al-Hojvīrī Abū’l Kalām Āzād Al-Huda International Abū’l-Fażl Bayhaqī Al-Huda International Institute of Islamic Educa- Abul Kalam tion for Women Abul Kalam Azad al-Hujwīrī Accusing Nafs (Nafs-e Lawwāma) ʿAlī Garshāsp Adaran Āl-i Sebüktegīn Afghan Claimants of Israelite Descent Āl-i Shansab Aga Khan Aliah Madrasah Aga Khan Development Network Aliah University Aga Khan Foundation Aligarh Muslim University Aga Khanis Aligarh Muslim University, AMU Agyaris Allama Ahl al-Malāmat Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-Mashriqi Aḥmad Khān Allama Mashraqi Ahmad Raza Khan Allama Mashraqui # Springer Science+Business Media B.V., part of Springer Nature 2018 827 Z. R. Kassam et al. (eds.), Islam, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism, Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1267-3 828 List of Entries Allama Mashriqi Bangladesh Jamaati-e-Islam Allama Shibili Nu’mani Baranī, Żiyāʾ al-Dīn Allāmah Naqqan Barelvīs Allamah Sir Muhammad Iqbal Barelwīs Almaniyya BāyazīdAnṣārī (Pīr-i Rōshan) Almsgiving Bāyezīd al-Qannawjī,Muḥammad Ṣiddīq Ḥasan Bayhaqī,Abūl-Fażl Altaf Hussain Hali Bāzīd Al-Tawḥīd Bedil Amīr ‘Alī Bene Israel Amīr Khusrau Benei Manasseh Amir Khusraw Bengal (Islam and Muslims) Anglo-Mohammedan Law Bhutto, Benazir ʿAqīqa Bhutto, Zulfikar Ali Arezu Bīdel Arkān al-I¯mān Bidil Arzu Bilgrāmī, Āzād Ārzū, Sirāj al-Dīn ‘Alī Ḳhān (d. -

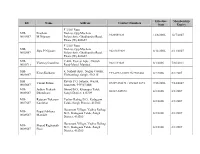

0001S07 Prashant M.Nijasure F 3/302 Rutu Enclave,Opp.Muchal

Effective Membership ID Name Address Contact Numbers from Expiry F 3/302 Rutu MH- Prashant Enclave,Opp.Muchala 9320089329 12/8/2006 12/7/2007 0001S07 M.Nijasure Polytechnic, Ghodbunder Road, Thane (W) 400607 F 3/302 Rutu MH- Enclave,Opp.Muchala Jilpa P.Nijasure 98210 89329 8/12/2006 8/11/2007 0002S07 Polytechnic, Ghodbunder Road, Thane (W) 400607 MH- C-406, Everest Apts., Church Vianney Castelino 9821133029 8/1/2006 7/30/2011 0003C11 Road-Marol, Mumbai MH- 6, Nishant Apts., Nagraj Colony, Kiran Kulkarni +91-0233-2302125/2303460 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0004S07 Vishrambag, Sangli, 416415 MH- Ravala P.O. Satnoor, Warud, Vasant Futane 07229 238171 / 072143 2871 7/15/2006 7/14/2007 0005S07 Amravati, 444907 MH MH- Jadhav Prakash Bhood B.O., Khanapur Taluk, 02347-249672 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0006S07 Dhondiram Sangli District, 415309 MH- Rajaram Tukaram Vadiye Raibag B.O., Kadegaon 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0007S07 Kumbhar Taluk, Sangli District, 415305 Hanamant Village, Vadiye Raibag MH- Popat Subhana B.O., Kadegaon Taluk, Sangli 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0008S07 Mandale District, 415305 Hanumant Village, Vadiye Raibag MH- Sharad Raghunath B.O., Kadegaon Taluk, Sangli 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0009S07 Pisal District, 415305 MH- Omkar Mukund Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0010S07 Vartak Sangli District, 415303 MH MH- Suhas Prabhakar Audumbar B.O., Tasgaon Taluk, 02346-230908, 09960195262 12/11/2007 12/9/2008 0011S07 Patil Sangli District 416303 MH- Vinod Vidyadhar Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0012S07 Gowande Sangli District, 415303 MH MH- Shishir Madhav Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0013S07 Govande Sangli District, 415303 MH Patel Pad, Dahanu Road S.O., MH- Mohammed Shahid Dahanu Taluk, Thane District, 11/24/2005 11/23/2006 0014S07 401602 3/4, 1st floor, Sarda Circle, MH- Yash W. -

E-Auction # 28

e-Auction # 28 Ancient India Hindu Medieval India Sultanates of India Mughal Empire Independent Kingdom Indian Princely States European Colonies of India Presidencies of India British Indian World Wide Medals SESSION I SESSION II Saturday, 24th Oct. 2015 Sunday, 25th Oct. 2015 Error-Coins Lot No. 1 to 500 Lot No. 501 to 1018 Arts & Artefects IMAGES SHOWN IN THIS CATALOGUE ARE NOT OF ACTUAL SIZE. IT IS ONLY FOR REFERENCE PURPOSE. HAMMER COMMISSION IS 14.5% Inclusive of Service Tax + Vat extra (1% on Gold/Silver, 5% on other metals & No Vat on Paper Money) Send your Bids via Email at [email protected] Send your bids via SMS or WhatsApp at 92431 45999 / 90084 90014 Next Floor Auction 26th, 27th & 28th February 2016. 10.01 am onwards 10.01 am onwards Saturday, 24th October 2015 Sunday, 25th October 2015 Lot No 1 to 500 Lot No 501 to 1018 SESSION - I (LOT 1 TO 500) 24th OCT. 2015, SATURDAY 10.01am ONWARDS ORDER OF SALE Closes on 24th October 2015 Sl.No. CATEGORY CLOSING TIME LOT NO. 1. Ancient India Coins 10:00.a.m to 11:46.a.m. 1 to 106 2. Hindu Medieval Coins 11:47.a.m to 12:42.p.m. 107 to 162 3. Sultanate Coins 12:43.p.m to 02:51.p.m. 163 to 291 4. Mughal India Coins 02:52.p.m to 06:20.p.m. 292 to 500 Marudhar Arts India’s Leading Numismatic Auction House. COINS OF ANCIENT INDIA Punch-Mark 1. Avanti Janapada (500-400 BC), Silver 1/4 Karshapana, Obv: standing human 1 2 figure, circular symbol around, Rev: uniface, 1.37g,9.94 X 9.39mm, about very fine. -

Agro-Tourism: a Cash Crop for Farmers in Maharashtra (India)

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Agro-Tourism: A Cash Crop for Farmers in Maharashtra (India) Kumbhar, Vijay September 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/25187/ MPRA Paper No. 25187, posted 21 Sep 2010 20:11 UTC 1 Agro-Tourism: A Cash Crop for Farmers in Maharashtra (India) Abstract Tourism is now well recognised as an engine of growth in the various economies in the world. Several countries have transformed their economies by developing their tourism potential. Tourism has great capacity to generate large-scale employment and additional income sources to the skilled and unskilled. Today the concept of traditional tourism has been changed. Some new areas of the tourism have been emerged like Agro- Tourism. Promotion of tourism would bring many direct and indirect benefits to the people. Agro-tourism is a way of sustainable tourist development and multi-activity in rural areas through which the visitor has the opportunity to get aware with agricultural areas, agricultural occupations, local products, traditional food and the daily life of the rural people, as well as the cultural elements and traditions. Moreover, this activity brings visitors closer to nature and rural activities in which they can participate, be entertained and feel the pleasure of touring. Agro-Tourism is helpful to the both farmers and urban peoples. It has provided an additional income source to the farmers and employment opportunity to the family members and rural youth. But, there are some problems in the process of the development of such centres. Hence, the government and other related authorities should try to support these activities in Maharashtra for the rural development and increase income level of the farmers. -

Dynastic Lists and Genealogical Tables

DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES (1) The Bahamani Dynasty of the Deccan. (2) The Nizam Shahi Dynasty of Ahmadnagar. (3) The Adil Shahi Dynasty of Bijapur. (4) The Imad Shahi Dynasty of Berar. (5) The Qutb Shahi Dynasty of Golconda. (6) The Barid Shahi Dynasty of Bidar. (7) The Faruqi Dynasty of Khandesh. 440 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES THE BAHAMANI DYNASTY OF THE DECCAN Year of Accession Year of Accession A. H. A. D. 748 Ala-ud-din Bahman Shah 1347 759 Muhammad I 1358 776 Mujahid 1375 779 Daud 1378 780 Mahmud (wrongly called Muhammad II) . 1378 799 Ghiyas-ud-din 1397 799 Shams-ud-din 1397 800 Taj-ud-din-Firoz 1397 825 Ahmad, Vali 1422 839 Ala-ud-din Ahmad 1436 862 Humayun Zalim 1458 865 Nizam 1461 867 Muhammad III, Lashkari 1463 887 Mahmud 1482 924 Ahmad 1518 927 Ala-ud-din 1521 928 Wali-Ullah 1522 931 Kalimullah 1525 944 End of the dynasty 1538 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES 441 THE BAHAMANI DYNASTY OF THE DECCAN GENEALOGY (Figures in brackets denote the order of succession) 442 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES THE NIZAM SHAHI DYNASTY OF AHMADNAGAR Year of Accession Year of Accession A. H. A. D. 895 Ahmad Nizam Shah 1490 915 Burhan Nizam Shah I 1509 960 Husain Nizam Shah I 1553 973 Murtaza Nizam Shah I 1565 996 Husain Nizam Shah II 1588 997 Ismail Nizam Shah 1589 999 Burhan Nizam Shah II 1591 1001 Ibrahim Nizam Shah 1594 1002 (Ahmad-usurper) 1595 1003 Bahadur Nizam Shah 1595 1007 Murtaza Nizam Shah II 1599 1041 Husain Nizam Shah III 1631 1043 End of the Dynasty 1633 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES 443 444 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES THE ADIL SHAHI DYNASTY OF BIJAPUR Year of Accession Year of Accession A. -

Board of College and University Development, 26

Content I. University Authorities II. Convocation III. University Adminstration IV. Schools: Campus and Sub-Centre V. Affiliated Colleges-Activites VI. List of Affiliated Colleges VII. Statistical Table Appendix 1 Editorial We are very happy to present you the annual report of Academic year 2009-2010 of Swami Ramanand Teerth Marathwada University. Education is an important instrument to enrich human mind and personality. Higher education develops the life style of common man. Therefore University and affiliated colleges are conducting many student oriented projects. The physical and qualitative development of University is the result of Hon. Vice Chancellor Dr. Sarjerao Nimse’s exceptional and outstanding leadership. We can see the change at every sphere of life which is the result of dynamic progress of science, technology and communication. Globalization has changed the traditional old methods and more opportunities. In these circumstances University updated syllabus and made more constructive and structural changes. Hon. Vice Chancellor personally thinks that overall personal development of student is more important than mare bookish merit. Therefore more fundamental facilities are being provided to the students. We believe that University is making students more perfect for the world-competation. University granted autonomy to the educational schools so that they may necessarily change syllabus whenever they need and may form more transparency in it. In this way we believe that merit of students will increase day by day. Various scholarships are being granted to students on University level. Today we can see many students are working on various research projects. Now we can see that schools of Language, Literature and Cultural Studies, Media Studies, Education Studies, etc are working in separate buildings. -

Tropes of Early Islamic Settlement

EarlyEarly IslamicIslamic SettlementSettlement UrbanUrban andand RuralRural transformationstransformations TropesTropes ofof EarlyEarly IslamicIslamic SettlementSettlement BedouinizationBedouinization ofof thethe civilizationscivilizations ofof antiquityantiquity AssimilationAssimilation toto thethe luxuriesluxuries ofof civilizedcivilized lifelife NeglectNeglect andand Disorder,Disorder, RuptureRupture andand DeclineDecline SomeSome historicalhistorical realitiesrealities inin thethe settlementsettlement processprocess VastVast majoritymajority ofof ArabArab settlementsettlement waswas inin SyriaSyria andand IraqIraq MovementMovement ofof peoplespeoples waswas closelyclosely associatedassociated withwith thethe conquestsconquests andand thethe armyarmy TheThe emergenceemergence ofof thethe amsaramsar (s.(s. misrmisr)) asas nodesnodes forfor Arab/MuslimArab/Muslim settlementsettlement MaintainingMaintaining thethe productiveproductive capacitycapacity ofof thethe landland waswas reflectedreflected inin patternspatterns ofof landland tenuretenure TheThe ThunderingThundering ArabArab HoardsHoards CategoriesCategories ofof EarlyEarly IslamicIslamic UrbanismUrbanism beforebefore thethe AbbasidsAbbasids DeDe NovoNovo citiescities Amsar Qusur and planned towns (e.g. Ayla, Anjar) ExistingExisting CitiesCities Resettlement within the existing towns Building adjacent – variation of the misr concept Defensive settlement - Ribat, thughur and awasim Basra,Basra, KufaKufa andand thethe earliestearliest amsaramsar Conventional designation -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy.