Md 1D07fqtiw8.Jpg.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

A Finding Aid to the Perls Galleries Records, 1937-1997, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Perls Galleries Records, 1937-1997, in the Archives of American Art Julie Schweitzer January 15, 2009 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1937-1995.................................................................... 5 Series 2: Negatives, circa 1937-1995.................................................................. 100 Series 3: Photographs, circa 1937-1995.............................................................. 142 Series 4: Exhibition, Loan, and Sales Records, 1937-1995................................ -

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian American Art Museum Chronological List of Past Exhibitions and Installations on View at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery 1958-2016 ■ = EXHIBITION CATALOGUE OR CHECKLIST PUBLISHED R = RENWICK GALLERY INSTALLATION/EXHIBITION May 1921 xx1 American Portraits (WWI) ■ 2/23/58 - 3/16/58 x1 Paul Manship 7/24/64 - 8/13/64 1 Fourth All-Army Art Exhibition 7/25/64 - 8/13/64 2 Potomac Appalachian Trail Club 8/22/64 - 9/10/64 3 Sixth Biennial Creative Crafts Exhibition 9/20/64 - 10/8/64 4 Ancient Rock Paintings and Exhibitions 9/20/64 - 10/8/64 5 Capital Area Art Exhibition - Landscape Club 10/17/64 - 11/5/64 6 71st Annual Exhibition Society of Washington Artists 10/17/64 - 11/5/64 7 Wildlife Paintings of Basil Ede 11/14/64 - 12/3/64 8 Watercolors by “Pop” Hart 11/14/64 - 12/13/64 9 One Hundred Books from Finland 12/5/64 - 1/5/65 10 Vases from the Etruscan Cemetery at Cerveteri 12/13/64 - 1/3/65 11 27th Annual, American Art League 1/9/64 - 1/28/65 12 Operation Palette II - The Navy Today 2/9/65 - 2/22/65 13 Swedish Folk Art 2/28/65 - 3/21/65 14 The Dead Sea Scrolls of Japan 3/8/65 - 4/5/65 15 Danish Abstract Art 4/28/65 - 5/16/65 16 Medieval Frescoes from Yugoslavia ■ 5/28/65 - 7/5/65 17 Stuart Davis Memorial Exhibition 6/5/65 - 7/5/65 18 “Draw, Cut, Scratch, Etch -- Print!” 6/5/65 - 6/27/65 19 Mother and Child in Modern Art ■ 7/19/65 - 9/19/65 20 George Catlin’s Indian Gallery 7/24/65 - 8/15/65 21 Treasures from the Plantin-Moretus Museum Page 1 of 28 9/4/65 - 9/25/65 22 American Prints of the Sixties 9/11/65 - 1/17/65 23 The Preservation of Abu Simbel 10/14/65 - 11/14/65 24 Romanian (?) Tapestries ■ 12/2/65 - 1/9/66 25 Roots of Abstract Art in America 1910 - 1930 ■ 1/27/66 - 3/6/66 26 U.S. -

NCN Articles of Interest | June 4, 2021

ARTICLES OF INTEREST June 4, 2021 QUOTE(S) OF THE WEEK “Creativity is not simply a property of exceptional people but an exceptional property of all people” – Ron Carter “Hire/promote for demonstrated curiosity.” – Tom Peters “Mathematics is not about numbers, equations, computations, or algorithms: it is about understanding.” – William Paul Thurston “If the Internet teaches us anything, it is that great value comes from leaving core resources in a commons, where they're free for people to build upon as they see fit.” – Lawrence Lessig “Love the battle between chaos and imagination.” – Robert Fulghum VIDEO(S) OF THE WEEK Discussion on Harnessing Culture and Heritage for economic transformation UN Office of the Special Adviser on Africa Bug Expert Explains Why Cicadas Are So Loud WIRED 5 Minutes That Will Make You Love Percussion The New York Times The Right Stuff: What It Takes to Boldly Go World Science Festival Cosmology and the Accelerating Universe | A Conversation with Nobel Laureate Brian Schmidt World Science Festival Meera Lee Patel: Making Friends with Your Fear CreativeMorning | Nashville FEATURED EVENTS/OPPORTUNITIES Viewfinder: Women’s Film and Video from the Smithsonian Because of HER Story | Smithsonian Monthly Series | First Thursday of the Month Black creatives never stopped creating Chicago Reader Through July 4 NEW Join Us for a Live Webinar on Famous 'Late Bloomers' and the Secrets of Midlife Creativity Smithsonian Magazine Event June 8 at 7 p.m. ET NEW Author and neurobiologist to discuss Art and the Brain June 8 Cape -

A Finding Aid to the Florence Knoll Bassett Papers, 1932-2000, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Florence Knoll Bassett Papers, 1932-2000, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie Ashley Funding for the digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. 2001 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, 1932-1999............................................................. 6 Series 2: Selected Publications, 1946-1990, 1999.................................................. 7 Series 3: Drawings, Sketches, and Designs, 1932-1984, 1999.............................. -

Opens in a Cascade of Trapezoidal Shapes, Like Shards of Glass

World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize 2008 award to Brenne Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH For the restoration of the ADGB Trade Union School (1928–1930) Bernau, Germany designed by Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer 1 2 This restoration highlights and emphasizes a particular approach to historic preservation that is perhaps the most sensible and intellectually satisfying today. Brenne Gesellschaft von Architekten is probably Germany’s most engaged and thoughtful restorer of classic Modern architecture. —Dietrich NeumaNN, JUROR Pre-restoration During the period in which the ADGB building was under East German control, it was impossible to find appropriate glass for repairs, so the light-filled glass corridor was obscured by a wooden parapet. Brenne Gesellschaft von Architekten restored the original materials and reintroduced the original bright red color of the steel framing. 3 Many of the building’s steel casement windows are highly articulated. The glass in the external staircase opens in a cascade of trapezoidal shapes, like shards of glass. 4 Despite Modernism’s influential place in our architectural heritage, many significant Modern buildings are endangered because of neglect, perceived obsolescence, inappropriate renovation, or even the imminent danger of demolition. In response to these threats, in 2006, the World Monuments Fund launched its Modernism at Risk Initiative with generous support from founding sponsor Knoll, Inc. The World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize was established as part of this initiative to demonstrate that Modern buildings can remain sustainable structures with vital futures. The Prize, which will be awarded biennially, recognizes innovative architectural and design solutions that preserve or enhance Modern landmarks and advances recognition of the special challenges of conserving Modern architecture. -

December 2013

DECEMBER 2013 INSIDE NEWS THIS MONTH MAD FOR RETRO Springfield A retro trend in office furniture has made a comeback in the workplace, according to central Illinois office furniture business owners and managers. business journal P. 5 (217) 726-6600 • [email protected] www.springfieldbusinessjournal.com FOOD FOR THOUGHT There has been a resurgence of interest in the food co-op movement as people become E-powerment more aware about where the food they put in their mouth into the power of the Internet collection of data, work to pro- one another, it is quite easy to Broadband Illinois, ANPI comes from and how it is grown. and its multi-faceted communi- vide coverage where there is see how their work relates. If accelerates Internet cation uses. But utilizing those none and promote broadband Broadband Illinois instigates the P. 12-13 By Gabe House, services in more rural areas can education. ANPI LLC, a busi- propagation of broadband ser- Correspondent be a daunting, if not downright ness communications solutions vice, ANPI later steps in – with impossible task. provider, has begun to roll out the help of existing rural tele- GETTING NAKED Guest columnist Bridget Broadband Internet and te- Two Springfield-based orga- comprehensive cloud-based communications providers - to Ingebrigtsen reviews Patrick lephony services are seemingly nizations are working to change communications solutions with help small and medium-sized Lencioni’s book about being ubiquitous for urban areas. that, though. Broadband Illinois existing providers to rural small business owners better utilize vulnerable, fears that sabotage There is no shortage of provid- is a non-profit entity with three businesses. -

An Exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art, Broad And

DIRECTORS' CHOICE mg PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM COLLEGE OF ART 85*h Anniversary Year • 1876-1961 Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2011 witii funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/directorschoiceeOOphil DIRECTORS' CHOICE AN EXHIBITION AT THE PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM COLLEGE OF ART, BROAD AND PINE STREETS, JANUARY 14 THROUGH FEBRUARY 7, 1961 The Dean and the eleveyi Department Directors of the Philadelphia Museum College of Art have assigned theynselves the task of choosing for exhibition the work of those artists and designers who, i.yi their judgment, have made a sigriificant, creative contribution to their profession and of explaining their reasons for making this selection. INDEX E. M. BENSON, Dean page 3 JOHN HUBLEY Filmmaker RAYMOND A. BALLINGER Advertising Design 4 PAUL DARROW Art Director 5 WALTER REINSEL Art Director 6 ANTONIO FRASCONI Printmaker 7 HERB LUBALIN Graphic Designer LOUISE B. BALLINGER Art Education HELEN BORTEN Author and Illustrator HENRY MITCHELL Sculptor WILLIAM PARRY Dimensional Design 10 ERWINHAUER Sculptor-Ceramist 11 JOHN MASON Sculptor-Ceramist JACK LENOR LARSEN Fabric Design 12 LENORE TAWNEY Weaver 13 ED ROSSBACH Weaver DOROTHY PARKE Fashion Design 14 BONNIE CASH IN Fashion Designer 15 NORMAN NORELL Fashion Designer CLARISSA ROGERS Fashion Illustration 18 RENE BOUCHE Fashion Illustrator 19 DOROTHY HOOD Fashion Illustrator GEORGE BUNKER General Arts 20 LEE GATCH Painter 21 GABRIEL KOHN Sculptor 22 GABOR PETERDI Printmaker ALBERT GOLD Illustration 23 RUDOLF FREUND Illustrator 24 MORTON ROBERTS Illustrator 25 ROBERT WEAVER Illustrator JOSEPH CARREIRO Industrial Design 26 DAVE CHAPMAN Industrial Designer 27 RICHARD S. LATHAM Industrial Designer GEORGE MASON Interior Design 28 CHARLES EAMES Artist-Designer and Filmmaker 29 FLORENCE KNOLL Interior and Furniture Designer SOL MEDNICK Photography 30 HARRY CALLAHAN Photographer 31 ROBERT L. -

The Stubbornness of Space Architecture and Design Special Issue

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2015 39/01 US $7 CAAN $9 UK £66 EUU €8 Architecture andDesignspecialissue The StubbornnessofSpace ART PAPERS ART 3 Multiple 48 Strange Shapes Letter from the GuestGuest EditorEditor david reinfurt (o-r-g) mtwtf This issue is aboutout spacespacece andan place, and various What does it mean to make One person one vote — sort of. attempts to engagegage or overcomeoverovercc them. In my old an artist’s multiple now? A design commission considers neighborhood inn SanSan Francisco,Franciranciss controversy roils over A software commission. the geometry of gerrymandering. rising rents, no-faultfault evictions,evictioctionn and clashing cultures, as Silicon Valleyy companiesanies move northward into a 14 Logistics Make the World 50 The Knoll Transcripts historically diverserse city. BeyBeyoBeyondo issues of gentrifica- jesse lecavalier margot weller tion, or the neighborlinesshborlinessess ofof corporations, the conflict has improbable roots inn the region.r Fred Turner’s book Synchronizing the world of Previously unpublished From Counterculture1ulture too CybercultureCyCybb (2006) charts commerce means attempting interviews with Knoll designers the evolution from the Bay Area communes of the to overcome time and space. revise the story of midcentury 1960s to the Silicon Valley of the 1990s. This evolution A study of logistics with a photo modernism. was premised on a belief in the power of networked essay on UPS. information technologies to emancipate users from 58 Concept Models body and physical space — if sometimes to the ne- 22 Losing Interest allied works architecture glect of the social, political, and environmental infra- shumon basar structures that support them. Turner’s social critique Beyond site or program, these has new salience in a moment of social media. -

Summer 2021 7/24/2021-7/25/2021 LOT # LOT

Summer 2021 7/24/2021-7/25/2021 LOT # LOT # 1 Chinese 14K Gold Figural Dragon on Stand 3 8 pcs. Meiji Japanese Silver Tea Set, Iris Decorat Chinese 14K gold (tested) figural dragon, Asian Export Sterling Silver Tea Service with depicted standing with raised head. Fitted with high relief iris decorations, eight (8) pieces. a conforming hardwood stand. 2" H x 3 1/2" W. ARTHUR & BOND, STERLING, and 73.3 grams. Provenance: the estate of Camille YOKOHAMA stamped to underside of bases. Gift, Nashville, Tennessee by descent from Sara Includes a kettle on stand, coffee pot, teapot, tea Joan Wilde (1923-2014), Colorado Springs, caddy, covered sugar bowl, creamer, CO. Mrs. Wilde and her husband, Lt. Col. Adna double-handled waste bowl, and a pair of sugar Godfrey Wilde (1920-2008) traveled tongs. Also includes an International Silver extensively throughout Asia as part of his career Company burner. Pieces ranging in size from 9 as an officer with the U.S. Army. Condition: 3/4" H x 8" W to 1" H x 5" L. 116.60 total troy Overall very good condition. 2,400.00 - ounces. Meiji Period. Provenance: private 2,600.00 Chattanooga collection. Consignor's Quantity: 1 grandparents acquired this set and the Arthur & Bond teacups also in this auction (see lot #3) while traveling in Asia in the early 1900s. Condition: All items in overall very good condition. Handles slightly loose to teapots. 2 Asian Export Silver Cocktail Set, incl. Shaker, Be 4,800.00 - 5,200.00 Japanese export silver cocktail set, comprised of Quantity: 1 one (1) shaker, eight (8) beaker style liqueur cups, and one (1) tray with wooden center insert and silver rim, 14 items total. -

Herbert Matter Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4p3021rd No online items Guide to the Herbert Matter Papers Jeffrey C. Head, et al. Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc/ © 2005 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Herbert Matter M1446 1 Papers Guide to the Herbert Matter Papers Collection number: M1446 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Processed by: Jeffrey C. Head, et al. Date Completed: December, 2005 Encoded by: Bill O'Hanlon © 2005 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Herbert Matter papers Dates: ca. 1937-1984 Collection number: M1446 Creator: Matter, Herbert, 1907-1984 Collection Size: ca. 310 linear feet Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Abstract: Original artwork, photographs, letters, manuscripts, process materials, memorabilia, negatives, transparencies, film, printed material, and working equipment. Physical location: Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least 24 hours in advance of intended use. Publication Rights Property rights reside with the repository. Literary rights reside with the creators of the documents -

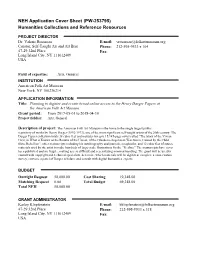

American Folk Art Museum

NEH Application Cover Sheet (PW-253795) Humanities Collections and Reference Resources PROJECT DIRECTOR Dr. Valerie Rousseau E-mail: [email protected] Curator, Self-Taught Art and Art Brut Phone: 212-595-9533 x 104 47-29 32nd Place Fax: Long Island City, NY 111012409 USA Field of expertise: Arts, General INSTITUTION American Folk Art Musuem New York, NY 100236214 APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Planning to digitize and create broad online access to the Henry Darger Papers at the American Folk Art Museum. Grant period: From 2017-05-01 to 2018-04-30 Project field(s): Arts, General Description of project: The American Folk Art Museum is the home to the single largest public repository of works by Henry Darger (1892-1973), one of the most significant self-taught artists of the 20th century. The Darger Papers collection totals 38 cubic feet and includes his epic 15,145-page novel called “The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion”, other manuscripts including his autobiography and journals, scrapbooks, and 12 cubic feet of source materials used by the artist to make hundreds of large-scale illustrations for the “Realms.” The manuscripts have never been published and are fragile, making access difficult and necessitating minimal handling. The grant will be used to consult with copyright and technical specialists, determine which materials will be digitized, complete a conservation survey, convene a panel of Darger scholars, and consult with digital humanities experts. BUDGET Outright Request 50,000.00 Cost Sharing 19,348.00 Matching Request 0.00 Total Budget 69,348.00 Total NEH 50,000.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Karley Klopfenstein E-mail: [email protected] 47-29 32nd Place Phone: 212-595-9533 x 318 Long Island City, NY 111012409 Fax: USA American Folk Art Museum Digitizing the Henry Darger Papers 1.