Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

A Finding Aid to the Perls Galleries Records, 1937-1997, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Perls Galleries Records, 1937-1997, in the Archives of American Art Julie Schweitzer January 15, 2009 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1937-1995.................................................................... 5 Series 2: Negatives, circa 1937-1995.................................................................. 100 Series 3: Photographs, circa 1937-1995.............................................................. 142 Series 4: Exhibition, Loan, and Sales Records, 1937-1995................................ -

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian American Art Museum Chronological List of Past Exhibitions and Installations on View at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery 1958-2016 ■ = EXHIBITION CATALOGUE OR CHECKLIST PUBLISHED R = RENWICK GALLERY INSTALLATION/EXHIBITION May 1921 xx1 American Portraits (WWI) ■ 2/23/58 - 3/16/58 x1 Paul Manship 7/24/64 - 8/13/64 1 Fourth All-Army Art Exhibition 7/25/64 - 8/13/64 2 Potomac Appalachian Trail Club 8/22/64 - 9/10/64 3 Sixth Biennial Creative Crafts Exhibition 9/20/64 - 10/8/64 4 Ancient Rock Paintings and Exhibitions 9/20/64 - 10/8/64 5 Capital Area Art Exhibition - Landscape Club 10/17/64 - 11/5/64 6 71st Annual Exhibition Society of Washington Artists 10/17/64 - 11/5/64 7 Wildlife Paintings of Basil Ede 11/14/64 - 12/3/64 8 Watercolors by “Pop” Hart 11/14/64 - 12/13/64 9 One Hundred Books from Finland 12/5/64 - 1/5/65 10 Vases from the Etruscan Cemetery at Cerveteri 12/13/64 - 1/3/65 11 27th Annual, American Art League 1/9/64 - 1/28/65 12 Operation Palette II - The Navy Today 2/9/65 - 2/22/65 13 Swedish Folk Art 2/28/65 - 3/21/65 14 The Dead Sea Scrolls of Japan 3/8/65 - 4/5/65 15 Danish Abstract Art 4/28/65 - 5/16/65 16 Medieval Frescoes from Yugoslavia ■ 5/28/65 - 7/5/65 17 Stuart Davis Memorial Exhibition 6/5/65 - 7/5/65 18 “Draw, Cut, Scratch, Etch -- Print!” 6/5/65 - 6/27/65 19 Mother and Child in Modern Art ■ 7/19/65 - 9/19/65 20 George Catlin’s Indian Gallery 7/24/65 - 8/15/65 21 Treasures from the Plantin-Moretus Museum Page 1 of 28 9/4/65 - 9/25/65 22 American Prints of the Sixties 9/11/65 - 1/17/65 23 The Preservation of Abu Simbel 10/14/65 - 11/14/65 24 Romanian (?) Tapestries ■ 12/2/65 - 1/9/66 25 Roots of Abstract Art in America 1910 - 1930 ■ 1/27/66 - 3/6/66 26 U.S. -

Cityland New Filings & Decisions | November 2013 Ulurp Pipeline

CITYLAND NEW FILINGS & DECISIONS | NOVEMBER 2013 ULURP PIPELINE New Applications Certified into ULURP PROJECT DESCRIPTION COMM. BD. ULURP NO. CERTIFIED 300 Lafayette Street Zoning text amendment and special permits MN 2 N140092ZRM; 10/7/2013 140093ZSM; 140095ZSM; 140096ZSM 688 Broadway Special permits MN 2 140055ZSM; 10/21/2013 140056ZSM 606 West 57th Street Zoning map amendment, zoning text amendments, special MN 4 130336ZMM; 10/21/2013 permit and authorization N130337ZRM; N130338ZRM; 130339ZSM; 130340ZAM Franklin Avenue Shuttle Bridges City map amendment BK 9 010345MMK; 10/21/2013 010371MMK; 010415MMK; 010421MMK Bergen Saratoga Apartments UDAAP designation, project approval and disposition of a c-o-p BK 16 140115HAK 10/7/2013 Yeshiva Rambam Disposition of City-owned property BK 18 140122PPK 10/21/2013 Braddock-Hillside Rezoning Zoning map amendment QN 13 140037ZMQ 10/21/2013 BSA PIPELINE New Applications Filed with BSA October 2013 APPLICANT PROJECT/ADDRESS DESCRIPTION APP. NO. REPRESENTATIVE VARIANCES Susan Golick 220 Lafayette St., MN Build residential building with ground-floor commercial use 294-13-BZ Marvin B. Mitzner Michael Trebinski 2904 Voorhies Ave., BK Enlarge 1-story dwelling (fl. area, lot coverage, parking) 286-13-BZ Eric Palatnik, PC N.Y. Methodist Hospital 473 6th St., BK Develop ambulatory care facility 289-13-BZ Kramer Levin Congregation Bet Yaakob 2085 Ocean Pkwy., BK Construct house of worship 292-13-BZ Sheldon Lobel, PC 308 Cooper LLC 308 Cooper St., BK Develop residential building in M1-1 district 297-13-BZ Sheldon Lobel, PC 134-22 35th Ave. LLC 36-41 Main St., QN Waive reqs. for fl. -

NCN Articles of Interest | June 4, 2021

ARTICLES OF INTEREST June 4, 2021 QUOTE(S) OF THE WEEK “Creativity is not simply a property of exceptional people but an exceptional property of all people” – Ron Carter “Hire/promote for demonstrated curiosity.” – Tom Peters “Mathematics is not about numbers, equations, computations, or algorithms: it is about understanding.” – William Paul Thurston “If the Internet teaches us anything, it is that great value comes from leaving core resources in a commons, where they're free for people to build upon as they see fit.” – Lawrence Lessig “Love the battle between chaos and imagination.” – Robert Fulghum VIDEO(S) OF THE WEEK Discussion on Harnessing Culture and Heritage for economic transformation UN Office of the Special Adviser on Africa Bug Expert Explains Why Cicadas Are So Loud WIRED 5 Minutes That Will Make You Love Percussion The New York Times The Right Stuff: What It Takes to Boldly Go World Science Festival Cosmology and the Accelerating Universe | A Conversation with Nobel Laureate Brian Schmidt World Science Festival Meera Lee Patel: Making Friends with Your Fear CreativeMorning | Nashville FEATURED EVENTS/OPPORTUNITIES Viewfinder: Women’s Film and Video from the Smithsonian Because of HER Story | Smithsonian Monthly Series | First Thursday of the Month Black creatives never stopped creating Chicago Reader Through July 4 NEW Join Us for a Live Webinar on Famous 'Late Bloomers' and the Secrets of Midlife Creativity Smithsonian Magazine Event June 8 at 7 p.m. ET NEW Author and neurobiologist to discuss Art and the Brain June 8 Cape -

GOOD DESIGN 5TH ANNIVERSARY Momaexh 0570 Masterchecklist 100 Museum Selections

GOOD DESIGN 5TH ANNIVERSARY MoMAExh_0570_MasterChecklist 100 Museum Selections Trends In Designer Training Popular Sellers Selection Committees, 1950-1954 Directory of Sources 100 MUSEUM SELECTIONSFROM GOOD DESIGN 1950-1954 The first retrospective selection of progressive furnishings available on the American market since 1950 is presented here. Thousands of items already chosen for Good Design season by season were reviewed in the light of longer experience by a special 5th Anniversary Selection Com- mittee composed of Museum of Modern Art staff members. This committee selected 100 prod- ucts (or groups of related products) for visual excellence. The Director of the Museum, Rene d'Harnoncourt, was joined by the Director of the Museum's Collections, Alfred H. Barr, Jr.; the Director of Circulating Exhibitions, Porter McCray; the Director of the Department of Architec- ture and Design, Philip C. Johnson; and the Director of Good Design, Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., in this Selection Committee. SHOWN APPROX. MANUFACTURER GOOD OR DISTRIBUTOR DESIGN ITEM RETAIL DESIGNER FURNITURE Darrell Londrum Avard 1951 Jan. A' _'of';. ., :'-VAI Bench, iron, foam rubber $ 78.00 (fabric, Boris Kroll) in muslin MoMAExh_0570_MasterChecklist 1952 Jan. Dining tcble, oblong; iron, white linoleum $157.50 Dorrell landrum Avard fl.,..} .~ .. ~-~ vA' / Finn Juhl Baker Furniture Co. 1952 Jan. VA3 Armchair, walnut. black leather $212.00 1953 Jan. Armchair, bent wood, natural webbing $ 95.00 Bruno Mathison Bonniers I· 113·" .~~~1"'1'4 p..Ji H p.Ottoman, bent wood, natural webbing $ 40.00 ("07 Bonniers 1954 Jan. V::s Table, low, teak plywood, beech $150.00 Bruno Mathsson Harold Cohen Designers in Production 1954 Jan. -

The Decade That Shaped Television News

The Decade That Shaped Television News CBS in the 1950s Sig Mickelson 2 e' The Decade i That Shaped About the Author SIG MICKELSON is aResearch Fellow Television News at the Hoover Institution at Stanford CBS in the 1950s University and Distinguished Professor of Journalism at the Manship School of Sig Mickelson Mass Communication at Louisiana State University. He has served as Vice President This insider's account, written by the first of CBS, Inc., and was the first president of president of CBS News, documents the CBS News. He is the author of America's meteoric rise of television news during the Other Voice (Praeger, 1983) and From 1950s. From its beginnings as anovelty with Whistle Stop to Sound Bite (Praeger, 1989), little importance as adisseminator of news, and the editor of The First Amendment— to an aggressive rival to newspapers, radio, The Challenge of New Technology and news magazines, television news (Praeger, 1989). became the most respected purveyor of information on the American scene despite insufficient funding and the absence of trained personnel. Mickelson's fascinating account shows the arduous and frequently critical steps undertaken by inexperienced staffs in the development of television news, documentaries, and sports broadcasts. He provides atreasure trove of facts and anecdotes about plotting in the corridors, the ascendancy of stars such as Edward R. Murrow, and the retirement into oblivion of the less favored. In alittle more than a decade, television reshaped American life. How it happened is afascinating story. ISBN: 0-275-95567-2 Praeger Publishers 88 Post Road West Westport, CT 06881 Jacket design by Double R Design, Inc. -

A Finding Aid to the Florence Knoll Bassett Papers, 1932-2000, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Florence Knoll Bassett Papers, 1932-2000, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie Ashley Funding for the digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. 2001 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, 1932-1999............................................................. 6 Series 2: Selected Publications, 1946-1990, 1999.................................................. 7 Series 3: Drawings, Sketches, and Designs, 1932-1984, 1999.............................. -

The Bloom Is on the Roses

20100426-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 4/23/2010 7:53 PM Page 1 INSIDE IT’S HAMMERED TOP STORIES TIME Journal v. Times: Story NY’s last great Page 3 Editorial newspaper war ® Page 10 PAGE 2 With prices down and confidence up, VOL. XXVI, NO. 17 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM APRIL 26-MAY 2, 2010 PRICE: $3.00 condo buyers pull out their wallets PAGE 2 The bloom is on the Roses Not bad for an 82-year-old, Adam Rose painted a picture of a Fabled real estate family getting tapped third-generation-led firm that is company that has come a surpris- for toughest property-management jobs known primarily as a residential de- ingly long way from its roots as a veloper. builder and owner of upscale apart- 1,230-unit project.That move came In a brutal real estate market, ment houses. BY AMANDA FUNG just weeks after Rose was brought in some of New York’s fabled real es- Today, Rose Associates derives as a consultant—and likely future tate families are surviving and some the bulk of its revenues from a broad just a month after Harlem’s River- manager—for another distressed are floundering, but few are blos- menu of offerings. It provides con- A tale of 2 eateries: ton Houses apartment complex was residential property, the vast soming like the Roses.In one of the sulting for other developers—in- taken over, owners officially tapped Stuyvesant Town/Peter Cooper Vil- few interviews they’ve granted,first cluding overseeing distressed prop- similar starts, very Rose Associates to manage the lage complex in lower Manhattan. -

Furniture E List

FURNITURE MODERNISM101.COM All items are offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days of receipt unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. Returns must be made conscien- tiously and expediently. The usual courtesy discount is extended to bonafide booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogs or stock. There are no library or institutional discounts. We accept payment via all major credit cards through Paypal. Institutional billing requirements may be accommodated upon request. Foreign accounts may remit via wire transfer to our bank account in US Dollars. Wire transfer details available on request. Terms are net 30 days. Titles link directly to our website for pur- chase. E-mail orders or inquiries to [email protected] Items in this E-List are available for inspection via appointment at our office in Shreveport. We are secretly open to the public and wel- come visitors with prior notification. We are always interested in purchasing single items, collections and libraries and welcome all inquiries. randall ross + mary mccombs modernism101 rare design books 4830 Line Avenue, No. 203 Shreveport, LA 71106 USA The Design Capitol of the Ark -La-Tex [ALVAR AALTO] Finsven Inc. 1 AALTO DESIGN COLLECTION FOR MODERN LIVING $350 New York: Finsven Inc., May 1955 Printed stapled wrappers. 24 pp. Black and white halftones and furniture specifications. Price list laid in. Housed in original mailing envelope with Erich Dieckmann a 1955 postage cancellation. A fine set. -

Opens in a Cascade of Trapezoidal Shapes, Like Shards of Glass

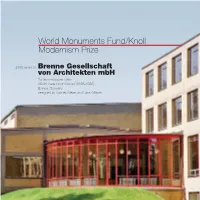

World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize 2008 award to Brenne Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH For the restoration of the ADGB Trade Union School (1928–1930) Bernau, Germany designed by Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer 1 2 This restoration highlights and emphasizes a particular approach to historic preservation that is perhaps the most sensible and intellectually satisfying today. Brenne Gesellschaft von Architekten is probably Germany’s most engaged and thoughtful restorer of classic Modern architecture. —Dietrich NeumaNN, JUROR Pre-restoration During the period in which the ADGB building was under East German control, it was impossible to find appropriate glass for repairs, so the light-filled glass corridor was obscured by a wooden parapet. Brenne Gesellschaft von Architekten restored the original materials and reintroduced the original bright red color of the steel framing. 3 Many of the building’s steel casement windows are highly articulated. The glass in the external staircase opens in a cascade of trapezoidal shapes, like shards of glass. 4 Despite Modernism’s influential place in our architectural heritage, many significant Modern buildings are endangered because of neglect, perceived obsolescence, inappropriate renovation, or even the imminent danger of demolition. In response to these threats, in 2006, the World Monuments Fund launched its Modernism at Risk Initiative with generous support from founding sponsor Knoll, Inc. The World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize was established as part of this initiative to demonstrate that Modern buildings can remain sustainable structures with vital futures. The Prize, which will be awarded biennially, recognizes innovative architectural and design solutions that preserve or enhance Modern landmarks and advances recognition of the special challenges of conserving Modern architecture. -

Bundle Music Channels

BUNDLE 200 USA Network 309 Fox Sports Southeast HD 264 VH1 206 A&E 43 H&I 411 Freeform HD 3 WACH - FOX MUSIC CHANNELS 242 AMC 204 Hallmark Channel 459 FX HD 18 WCES - PBS Included with the Bundle 102 Animal Planet 246 Hallmark Drama 460 FXX HD 37 Antenna 239 Hallmark Movies & Mysteries 243 WE 305 Golf Channel HD 700 MC Hit List 726 MC ‘90S 23 Weather Channel 701 MC Max 727 MC ‘80S 107 BBC America 133 HGTV 452 Hallmark HD 127 BBC World 100 History Channel 16 WGGS 702 MC Dance/EDM 728 MC ‘70S 449 Hallmark Drama HD 270 BET 14 HSN 9 WGN 703 MC Indie 729 MC Solid Gold Oldies 453 Hallmark Movies & Mysteries HD 10 WIS - NBC 704 MC Hip-Hop and R&B 730 MC Pop & Country 46 Bounce 245 IFC 443 HGTV HD MC Rap MC Today’s Country 213 Bravo 1 Inspiration 13 WKTC - MyTV 705 731 426 History HD 706 MC Hip-Hop Classics 732 MC Country Hits 155 Cartoon Network 126 Investigation Discovery 8 WLTX - CBS 535 HLN HD 707 MC Throwback Jams 733 MC Classic Country 258 CMT 40 Justice 5 WOLO - ABC 458 IFC HD 708 MC R&B Classics 734 MC Contemporary Christian 280 CNBC 48 Laff 19 WRET - SC Channel ETV 406 Investigation Discovery HD 709 MC R&B Soul 735 MC Pop Latino 283 CNN 201 Lifetime 11 WRLK - SC Channel ETV 450 Lifetime HD 710 MC Gospel 736 MC Musica Urbana 284 CNN Headline News 241 Lifetime Movies 7 WSPA - CBS 451 Lifetime Movies HD 711 MC Reggae 737 MC Mexicana 209 Comedy Central 202 Lifetime Real Women 4 WYFF - NBC MC Rock MC Tropicales 352 MLB HD 712 738 39 Comet 17 MeTV 12 WZRB - ION TV 713 MC Metal 739 MC Romances 432 MotorTrend HD 134 Cooking Channel