APR 2005 Critical Incidents in Teachers' Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; to Include the Property of a Lady

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; To Include The Property Of A Lady, Eaton Square, London ( 24 Mar 2021 B) Wed, 24th Mar 2021 Lot 213 Estimate: £100 - £200 + Fees A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES to include a 1930s rose gold organza with a gold jacquard embroidery evening dress, with a square neckline, gold jacquard and green chiffon straps, a v back neckline, a A-line skirt and a gold jacquard and green chiffon sash decorates the back of the dress (74 cm bust, 74 cm waist, 146 cm from shoulder to hem); a 1930s ivory lace sleeveless evening dress, with a v neckline, lace straps and buttons covered in lace are used as zipper on the back, a full skirt and a silk slip (65 cm bust, 61 cm waist, 145 cm from shoulder to hem), the evening dress comes with a matching ivory lace shrug; an 1960s ivory silk wedding dress, with a jewel neckline embellished with white lace, long sleeves, buttons covered in silk are used as zipper on the back, a skirt with white lace hem and a cathedral train (83 cm bust, 83 cm waist, 132 cm from shoulder to front hem), the wedding dress comes with a bridal flower crown with tulle veil; a 1940s ivory silk evening dress, with a square neckline embellished with ivory lace and net, beads and a beige flower applique, short sleeves embellished with taupe net, beads and ivory lace, a skirt with a chapel train and a silk slip (63 cm bust, 58 cm waist, 165 cm from shoulder to front hem), a 1960s baby blue tullle evening dress, with a sweetheart neckline with spaghetti straps and a full skirt made up of layers of tulle and silk, with original label 'Salon Moderne. -

2020 Appendixes

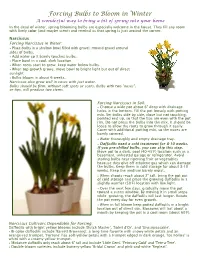

Forcing Bulbs to Bloom in Winter A wonderful way to bring a bit of spring into your home In the dead of winter, spring blooming bulbs are especially welcome in the house. They fill any room with lively color (and maybe scent) and remind us that spring is just around the corner. Narcissus Forcing Narcissus in Water: • Place bulbs in a shallow bowl filled with gravel; mound gravel around sides of bulbs. • Add water so it barely touches bulbs. • Place bowl in a cool, dark location. • When roots start to grow, keep water below bulbs. • When top growth grows, move bowl to bright light but out of direct sunlight. • Bulbs bloom in about 6 weeks. Narcissus also grow well in vases with just water. Bulbs should be firm, without soft spots or scars. Bulbs with two "noses", or tips, will produce two stems. Forcing Narcissus in Soil: • Choose a wide pot about 6” deep with drainage holes in the bottom. Fill the pot loosely with potting mix. Set bulbs side by side, close but not touching, pointed end up, so that the tips are even with the pot rim. Do not press the bulbs into the mix. It should be loose to allow the roots to grow through it easily. Cover with additional potting mix, so the noses are barely covered. • Water thoroughly and empty drainage tray. • Daffodils need a cold treatment for 8-10 weeks. If you pre-chilled bulbs, you can skip this step. Move pot to a dark, cool (40-45°F) location such as a basement, unheated garage or refrigerator. -

Make Your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…

Make your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…. 1355 W 20 th Avenue Oshkosh, WI 54902 Phone: 920-966-1300 Friday and Sunday Bridal Package 2014 The following services and amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $600 deposit - $400 for banquet facility rental and $200 applied towards food and beverage Saturday Bridal Package 2014 The Following Services and Amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $1,000 deposit - $700 for banquet facility rental and $300 applied towards food and beverage $5,000 Food Minimum DINNER PLATED DINNER ENTREES POULTRY Chicken Forestiere 19.99 Chicken Piccata 19.99 6oz. -

Name Club Men Michael Hutchinson In-Gear

Category (Ages) Name Club Men Michael Hutchinson In-Gear Quickvit RT Bradley Wiggins Garmin Slipstream Ian Stannard ISD - Neri Chris Newton Rapha Condor Rob Hayles Halfords/Bikehut Nino Piccoli API Metrow/Silverhook Mark Holton Shorter Rochford RT/Exclusive Wouter Sybrandy Team Sigma Sport Matthew Bottrill I-Ride RT/MG Décor Jez Cox Team Bike & Run/Maximuscle Colin Robertson Equipe Velo Ecosse Phill Sykes VC St Raphael/Waite Contracts Gyles Wingate Bognor Regis CC Matt Clinton Mike Vaughan Cycles Ben Price Finchley Racing Team Jesse Elzinga Beeline Bicycles RT Thomas Weatherall Oxford University CC Michael Nicolson Dooleys RT David Mclean La Poste/Rent a Car Graeme Hatcher Manx Viking Wheelers-Shoprite Duncan Urquhart Endura Racing/Pedalpower Jerone Walters Team Sigma Sport Adam Hardy Wolds RT Ian Taylor NFM Racing Team Andy Hudson Cambridge CC Michael Bannister Bedfordshire RCC Daniel Patten Magnus Maximus Coffee.com Thomas Collier Pendragon Kalas Peter Wood Sheffrec CC Ben Williams New Brighton CC David Clarke Pendragon Kalas Sebastian Ader …a3rg/PB Science/SIS John Tuckett AW Cycles/Giant Dominic Sweeney Lutterworth Cycle Centre Tejvan Pettinger SRI Chinmoy Cycling Team Charles McCulloch Shorter Rochford RT/Exclusive Anton Blackie Oxford University CC James Smith Somerset RC Lee Tunnicliffe Fit-Four/Cycles Dauphin James Schofield Oxford University Tri Club Simon Gaywood Team Corley/Cervelo Robin Ovenden Caesarean CC Gordon Leicester Rondelli/Horton Blake Pond Southfork Racing.co.uk Andrew Porter Welwyn Wheelers Arthur Doyle Dooleys -

The Vasa Star

THETHE VASA VASA STAR STAR VasastjärnanVasastjärnan PublicationPublication of of THE THE VASA VASA ORDER ORDER OF OF AMERICA AMERICA JULY-AUGUSTJULY-AUGUST 2010 2010 www.vasaorder.comwww.vasaorder.com MEB-E Art Björkner MEB-W Ed Netzel MEB-M Sten Hult MEB-S Ulf Alderlöf MEB-C Ken Banks VGS Gail Olson GS Joan Graham VGM Tore Kellgren GM Bill Lundquist GT Keith Hanlon The Grand Master’s Message Bill Lundquist Dear Vasa Brothers and Sisters, they were when we were founded in 1896, promoting our cul- I humbly and proudly accept the most prestigious office as tural heritage and providing a program of social fellowship. Grand Master of the Vasa Order and thank you for graciously We have suffered losses by death but many from lack of inter- electing me. I assume this office with excitement and much est. I plan to put programs in place to give you ideas to help enthusiasm but well aware of the challenges ahead. I am keep your current members interested and active as well as grateful and truly appreciative of your confidence in my ability make more interesting to potential members. New members to lead the Order for the next four years. I pledge to you that I bring in new enthusiasm, new ideas and new workers. will do my utmost to fulfill the goals I have set for this term. Scandinavians are no strangers to challenges. One such These include but are not limited to goals in the following challenge for all of us over the next four years is the reduced areas: Improvement in transparency between the Grand Lodge budget to The Vasa Star. -

St Peter's College 12Th Annual Sports and Cultural Festival the Ethos Is

St Peter’s College 12th Annual Sports and Cultural Festival The 12th Annual St Peter’s College Sports and Cultural Festival is happening at the College in Sunninghill from Friday to Sunday, 18 – 20 September 2015. This year, we have 44 schools participating with over 110 teams comprising of about 3,500 high school children, plus spectators. This is the largest schools sports and cultural festival of its kind in South Africa. Our Festival is unique in that we bring children from all walks of life, underprivileged and privileged, together to engage with each other on a ‘level playing field’ to play sport and share cultural interests. Please take a few minutes to watch the video clip of the show SABC’s Expresso aired about the 2014 Festival: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gBaGAn_PSTU The Ethos is the Reason The ethos of the festival aligns with the core values of St Peter’s College ie. Relationships, Respect and Responsibility. The Festival has a social investment focus, centred on youth development, promoting partnership in communities and has a strong ‘Proudly South African’ tradition. The College encourages international sports and cultural events of the kind that provide our students with the opportunity to compete against teams from all economic backgrounds, cultures and countries. Principles of the Festival Activities at the Festival · Fair play · Inter-high Dance Competition · No alcohol · Soccer for boys and girls · Friendship · Basketball for boys and girls · Sports and cultural activities accessible · Netball to and enjoyed by South Africans · Chess · Public Speaking · Visual Arts ie. Street art · Music and Choir festival · Drama – Winning FEDA production · Grade 9 Entrepreneurship Market It’s all about the game - playing your best and loving it. -

P16 Layout 1 2/17/15 9:13 PM Page 1

p16_Layout 1 2/17/15 9:13 PM Page 1 WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2015 SPORTS FIS head laments drop in recreational skiers BEAVER CREEK: Sitting on a terrace on Colorado resorts of Vail/Beaver Creek come from their ski-mad nation. lost at the current rate. It is trend right champions the worlds were viewed as a a bluebird day overlooking the Birds of were projected to provide a $130 mil- But the numbers Kasper and other across Europe’s alpine arc with the sport chance to put skiing in the American Prey finish line, International Ski lion two-week jolt to the local economy. industry leaders are fixated on are the gaining ground in some areas and los- sporting spotlight. Gold medal perform- Federation (FIS) chief Gian Franco As advertised, the event delivered plen- participation figures that will ultimately ing traction in others. ances from Ted Ligety in the giant Kasper scanned the horizon for recre- ty of thrills and spills on the slopes and impact the FIS portfolio of world cham- “What is most interesting is the num- slalom and 19-year-old ski darling ational skiers that never appear. “Even in an adequate apres-ski buzz in Vail but pionships: alpine, nordic, freestyle, ber of new nations that are now becom- Mikaela Shiffrin were dramatic. the cold countries like Switzerland and for a large part was greeted with a snowboard and ski jumping. ing active within skiing, as an example But with the championships sand- Austria the number of kids being shrug. we now have Kazakhstan who are now wiched between the Super Bowl and involved in skiing goes down,” Kasper Vacancy signs flashed at hotels and LOSING TRACTION bidding for the Olympic Games,” said FIS the NBA All-Star weekend and qualify- told Reuters during a piste-side inter- resorts around the Vail valley while A federation that relies on snow as its general secretary Sarah Lewis. -

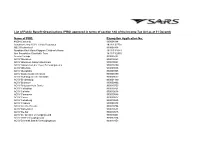

List of Section 18A Approved PBO's V1 0 7 Jan 04

List of Public Benefit Organisations (PBO) approved in terms of section 18A of the Income Tax Act as at 31 December 2003: Name of PBO: Exemption Application No: 46664 Concerts 930004984 Aandmymering ACVV Tehuis Bejaardes 18/11/13/2738 ABC Kleuterskool 930005938 Abraham Kriel Maria Kloppers Children's Home 18/11/13/1444 Abri Foundation Charitable Trust 18/11/13/2950 Access College 930000702 ACVV Aberdeen 930010293 ACVV Aberdeen Aalwyn Ouetehuis 930010021 ACVV Adcock/van der Vyver Behuisingskema 930010259 ACVV Albertina 930009888 ACVV Alexandra 930009955 ACVV Baakensvallei Sentrum 930006889 ACVV Bothasig Creche Dienstak 930009637 ACVV Bredasdorp 930004489 ACVV Britstown 930009496 ACVV Britstown Huis Daniel 930010753 ACVV Calitzdorp 930010761 ACVV Calvinia 930010018 ACVV Carnarvon 930010546 ACVV Ceres 930009817 ACVV Colesberg 930010535 ACVV Cradock 930009918 ACVV Creche Prieska 930010756 ACVV Danielskuil 930010531 ACVV De Aar 930010545 ACVV De Grendel Versorgingsoord 930010401 ACVV Delft Versorgingsoord 930007024 ACVV Dienstak Bambi Versorgingsoord 930010453 ACVV Disa Tehuis Tulbach 930010757 ACVV Dolly Vermaak 930010184 ACVV Dysseldorp 930009423 ACVV Elizabeth Roos Tehuis 930010596 ACVV Franshoek 930010755 ACVV George 930009501 ACVV Graaff Reinet 930009885 ACVV Graaff Reinet Huis van de Graaff 930009898 ACVV Grabouw 930009818 ACVV Haas Das Care Centre 930010559 ACVV Heidelberg 930009913 ACVV Hester Hablutsel Versorgingsoord Dienstak 930007027 ACVV Hoofbestuur Nauursediens vir Kinderbeskerming 930010166 ACVV Huis Spes Bona 930010772 ACVV -

Meriete 2002 Gebruiksafrikaans-Olimpiade

MERIETE 2002 GEBRUIKSAFRIKAANS-OLIMPIADE Waar leerlinge dieselfde punte behaal het, is van uitklop afdelings (soos deur die moderator aangewys) gebruik gemaak om die wenner aan te wys. Daar was vanjaar 414 skole en 9000 leerlinge wat vir dié Olimpiade ingeskryf het. Alle wenners ontvang 'n kontantbedrag sowel as intekening vir een jaar op die tydskrif "Insig". NASIONALE WENNERS Eerste plek: Carina Nel - Pretoria High School for Girls (Gauteng). Sy ontvang 'n prys met 'n totale waarde van R2000, bestaande uit 'n tjek en intekening op die tydskrif INSIG. Tweede plek: Keoma Wright - Crawford College North Coast (Kwazulu Natal). Hy ontvang 'n prys met 'n totale waarde van R1500, bestaande uit 'n tjek en intekening op die tydskrif INSIG. Derde plek: Amanda Bouwer - Clapham High School (Gauteng). Sy ontvang 'n prys met 'n totale waarde van R1000, bestaande uit 'n tjek en intekening op die tydskrif INSIG. PROVINSIALE WENNERS Die provinsiale wenners ontvang elk 'n prys ter waarde van R600 wat bestaan uit 'n tjek en intekening op die tydskrif INSIG. Gauteng: Estée Benadé, Roedean School (Houghton) Kwazulu Natal: Paul Dippenaar, Holy Family College (Congella) Namibië: Meike Engberts, Deutsche Höhre Privatschule (Windhoek) Mpumalanga: Arno Middelberg, Uplands College (Nelspruit) Noord-Kaap: Jeanne-Marié Roux, St Patrick's (Kimberley) Limpopo: Juanita Prinsloo, Capricorn High School (Pietersburg) Noord-Wes: Iwan Pieterse, Milner High School (Klerksdorp) Oos-Kaap: Annelie Maré, Collegiate Girls'High School (Port Elizabeth) Vrystaat: Didi Janse van -

Madame Bergman Ӧsterberg, Her Students and the Ling Association

Madame Bergman Ӧsterberg, her students and the Ling Association Their influence on the development of Netball 1895–1930 Jane Claydon 2021 This research publication was undertaken on behalf of The Ӧsterberg Collection Contents Topics covered include: 1 Basket- ball at Hampstead and Dartford Page 3 Dr Justin Kaye Toles 2 Influence of Senda Berenson and Ester Porter Page 8 ...and I went on a voyage to Sweden 3 Publicity References to Basket-Ball in a variety of publications Page 10 4 Net Ball introduced by Madame’s students in schools, colleges and factories Page 13 5 The Ling Association Foundation, early members and the drafting of the first rules of Net Ball Page 15 6 School Basket-Ball - information from school magazines online Page 18 7 The Specialist Colleges of Physical Education Page 21 8 The circulation of Net Ball rule books across the globe. Page 22 9 The founding of the AEWNA Page 24 10 Conclusion Page 26 11 Post Script Page 27 11 Additional information and further reading Page 28 12 References Page 29 Key: A name, followed by a date in brackets for example (1898), indicates a student trained at Madame Bergman Ӧsterberg College and the year they completed their training. There are many different spellings of basket-ball and netball in this document. Some references use upper case, others lower case. Some use a hyphen, others do not. As far as possible I have used the original text. However, even that sometimes varies, within a publication. It does not seem possible to overcome the inconsistencies. I am most grateful to the schools who have posted digitised archive material online. -

Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Grimoire University Publications Spring 2005 Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/grimoire Recommended Citation La Salle University, "Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005" (2005). Grimoire. 14. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/grimoire/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grimoire by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. spring 2005 volume 4 4 fetter from the editress “Staring at the blank page before you, Open up the dirty window, Let the sun illuminate the words that you could not find...” Each time the lyrics of Natasha Bedingfield’s “Unwritten” play over in my head, I can’t help but be reminded of the seemingly unattainable goals I dream up for myself every day. Not just the dream, but also the struggle to make those visions real— to voice the words and feelings that no one else can— quickly becomes more tiring and frustrating than life itself. Compared to the size of the whole, the simple goal of being published in this unknown, student-run maga zine is but a small accomplishment. This becomes obvious, as this book may eventually (and most likely will) pass from your hand, the reader’s, to the ground, or a trashcan, or— if we’re lucky— tossed out of a third-story dorm window. But the Grimoire is more than just a magazine— it’s a monument on which is carved the legacy of hundreds of students. -

Catching Fire. the Impressive Lineup Is Joined by the Hunger Games

Cast: Jennifer Lawrence, Josh Hutcherson, Liam Hemsworth, Woody Harrelson, Elizabeth Banks, Julianne Moore, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Jeffrey Wright, Willow Shields, Sam Claflin, Jena Malone, Natalie Dormer, with Stanley Tucci, and Donald Sutherland Directed by: Francis Lawrence Screenplay by: Peter Craig and Danny Strong Based upon: The novel “Mockingjay” by Suzanne Collins Produced by: Nina Jacobson, Jon Kilik SYNOPSIS The blockbuster Hunger Games franchise has taken audiences by storm around the world, grossing more than $2.2 billion at the global box office. The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 now brings the franchise to its powerful final chapter in which Katniss Everdeen [Jennifer Lawrence] realizes the stakes are no longer just for survival – they are for the future. With the nation of Panem in a full scale war, Katniss confronts President Snow [Donald Sutherland] in the final showdown. Teamed with a group of her closest friends – including Gale [Liam Hemsworth], Finnick [Sam Claflin] and Peeta [Josh Hutcherson] – Katniss goes off on a mission with the unit from District 13 as they risk their lives to liberate the citizens of Panem, and stage an assassination attempt on President Snow who has become increasingly obsessed with destroying her. The mortal traps, enemies, and moral choices that await Katniss will challenge her more than any arena she faced in The Hunger Games. The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 is directed by Francis Lawrence from a screenplay by Peter Craig and Danny Strong and features an acclaimed cast including Academy Award®-winner Jennifer Lawrence, Josh Hutcherson, Liam Hemsworth, Woody Harrelson, Elizabeth Banks, Academy Award®-winner Philip Seymour Hoffman, Jeffrey Wright, Willow Shields, Sam Claflin, Jena Malone with Stanley Tucci and Donald Sutherland reprising their original roles from The Hunger Games and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire.