King Richard Iii/Looking for Richard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Has Your Understanding of Ambition and Identity Been Informed by Exploring the Connections Between Richard III and Looking for Richard?

How has your understanding of ambition and identity been informed by exploring the connections between Richard III and Looking for Richard? Ambition and identity are two contextually transcendent facets of the human condition. This becomes apparent through the comparison of Shakespeare’s King Richard III (RIII) and Al Pacino’s “Looking For Richard” (LFR) as both texts explore the dynamics of ego, villainy, self-identity and representation of gender, yet are structurally, technically and contextually unalike. RIII is an English play from the late sixteenth century written for the stage, whereas LFR takes the form of an American docudrama which reshapes these core values of RIII in a modern setting. My understanding of RIII is also supported by Dr. Ian Frederick Moulton’s paper “‘A Monster Great Deformed’: The Unruly Masculinity of RIII.” One aspect of identity employed by Richard to achieve his ambitions is gender identity. Richard’s own masculinity is exhibited as he indulges in a hubristic soliloquy after ‘winning’ Lady Anne: “Was ever woman in this humour wooed? Was ever woman in this humour won?” Anaphora and rhetorical questioning emphasises Richard’s growing ego and hypermasculine disregard of women. Richard further displays his masculine identity by feigning feminine vulnerability – using gender identity and the personification of ‘beauty’ as a means of manipulation: “Nay, do not pause, for I did kill King Henry, but ‘twas thy beauty that provokèd me.” Moulton expands on this, “By offering Anne his sword, [Richard] stages a calculated (and illusory) gender reversal”. In LFR, director Al Pacino deliberately selects specific scenes from RIII to assess the relevance of Shakespeare in twenty first century America. -

The Appropriateness of William Shakespeare's

T.C. SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ İNGİLİZ DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI ANA BİLİM DALI İNGİLİZ DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI BİLİM DALI THE APPROPRIATENESS OF WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE'S RICHARD III TO FILM ADAPTATION YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ DANIŞMAN YRD. DOÇ. DR. GÜLBÜN ONUR HAZİRLAYAN ŞEFİKA BİLGE CANTEKİNLER KONYA, 2005 ÖZET 1930ların başında Hollywood ile birlikte yükselen Amerikan Film Endüstrisi vazgeçilmez kaynakları arasında ünlü İngiliz oyun yazarı William Shakespeare'in eserlerini ilk sıraya oturtmuştur. Sessiz sinemadan günümüz üç boyutlu animasyon film dönemine geçişte klasik Shakespeare oyunları da her yeni yönetmen ve yapımcıyla birlikte farklı bir boyut kazanmıştır. Tarihsel bir trajedi olan Shakespeare'in III. Richard adlı oyunu ilk oynandığı 1590lardan günümüze kadar geçen sürede en çok sahnelenen ama en az anlaşılan oyunlardan biri olmuştur. Buna bağlı olarak III. Richard'ın seçilen üç film uyarlaması oyunu farkh yonlerden ele almışlardır. İlk film İngiliz aktör- yönetmen Sir Laurence Oliver'in 1955 film uyarlaması III. Richard, ikincisi İngiliz yönetmen Richard Loncraine'in İngiliz aktör-yönetmen Ian McKellen ile birlikte çektiği 1995 yapımı III. Richard ve sonuncusu da Amerikalı aktör Al Pacino'nun yönetip başrol oynadığı Looking For Richard (Richard'ı Aramak) adlı filmidir. Bu çalışma, seçilen üç sahne ile oyunun kahramanı olan III. Richard'ın yükseliş ve çöküşünü temel alarak üç film uyarlaması arasındaki farklılıkları değerlendirmektedir. Ayrıca, a9ihs monoloğu, kur yapma, baştan çıkarma ile savaş sahneleri incelenerek bunların Shakespeare'in metnini ne derece yansıttıkları ve bu sahnelerin birbirinden nasıl farklı olarak ele alındığını belirtmektedir. ABSTRACT Within the rise of Hollywood productions at the beginning of the 1930s, American Film Industry put the works of famous British playwright William Shakespeare at its one of the most indispensable sources. -

2017-Richard-3-Learning-Resources

LEARNING RESOURCES SYNOPSIS 2 QUICK FACTS 3 PERFORMANCE HISTORY 4 SOURCES AND SHAKESPEARE SHAPING HISTORY 5 HISTORY OF WOMEN PLAYING MALE ROLES IN SHAKESPEARE 6 CHARACTERS 8 THEMES 12 FROM THE DIRECTOR 17 DESIGN 18 OTHER RESOURCES 21 ACTIVITIES 23 EXERCISE ONE 23 EXERCISE TWO 24 EXERCISE THREE 25 EXERCISE FOUR 26 LEARNING RESOURCES RICHARD 3 © Bell Shakespeare 2017, unless otherwise indicated. Provided all acknowledgements are retained, this material may be used, Page 1 of 26 reproduced and communicated free of charge for non-commercial educational purposes within Australian and overseas schools RICHARD 3 SYNOPSIS England is enjoying a period of peace after a long civil war between the royal families of York and Lancaster, in which the Yorks were victorious and Henry VI was murdered (by Richard). King Edward IV is newly declared King, but his youngest brother, Richard (Gloucester) is resentful of Edward’s power and the general happiness of the state. Driven by ruthless ambition and embittered by his own deformity, he initiates a secret plot to take the throne by eradicating anyone who stands in his path. Richard has King Edward suspect their brother Clarence of treason and he is brought to the Tower by Brackenbury. Richard convinces Clarence that Edward’s wife, Queen Elizabeth, and her brother Rivers, are responsible for this slander and Hastings’ earlier imprisonment. Richard swears sympathy and allegiance to Clarence, but later has him murdered. Richard then interrupts the funeral procession of Henry VI to woo Lady Anne (previously betrothed to Henry VI’s deceased son, again killed by Richard). He falsely professes his love for her as the cause of his wrong doings, and despite her deep hatred for Richard, she is won and agrees to marry him. -

Advanced Paper 2 Module a - Elective 1: Exploring Connections

Advanced Paper 2 Module A - Elective 1: Exploring Connections Analyse how the central values portrayed in King Richard III are creatively reshaped in Looking for Richard. Prescribed texts: King Richard III, William Shakespeare, c. 1593 Looking for Richard, Al Pacino, 1996 Al Pacino states in his docudrama, Looking for Richard, that he wants his film to show that Shakespeare’s King Richard III is about “how we think Opens with a quotation from and feel today.” This idea of enduring values is reinforced in the interview the text that leads to a close with the homeless man, who believes that Shakespeare “instructed us” and consideration of reshaping and a we still have lessons to learn from him about feeling and understanding. thesis about the influence of The sub-title of the film is ‘A four hundred-year-old work in progress’, context on values (directly suggesting that for Pacino there are central values and ideas in the play that connecting with words in remain relevant for contemporary audiences. However, because of the question) profound changes from Elizabethan England to modern American society and the differences between Shakespearean drama and documentary films, some reshaping and re-interpretation of the original play are necessary. Some of the central ideas and values in King Richard III examine the nature Form and values are identified of authority, the acquisition of power and the extent to which decisions and as part of context in each text actions are the result of free will or determinism. Shakespeare expresses these ideas through poetry, with its reliance on motif and extended metaphor, through characterisation and through the idea of metadrama. -

Shakespeare on Film- Looking for Richard

SHAKESPEAREONFILM LOOKING FOR RICHARD Teachers’ Notes This study guide is aimed at students of GCSE English and Media, A’ level English Media and Film and GNVQ Media: Communication and Production. Areas investigated include Filming Shakespeare, Language, Documentary Styles and Representation. This series of study guides aims to provide teachers with valuableresource materials for the teaching of Shakespeare throughout the National Curriculum. Synopsis The American actor Al Pacino is the co-producer, director and star of the film ‘Looking For Richard’. His project intertwines the telling of the story of Shakespeare’s ‘Richard III’ with an intimate look at the actors’ and filmmakers’ processes as they come to grips with their characterisations and with translating their enthusiasm for the play onto film. The film ‘Looking For Richard’ follows their debates and revelations about the play, takes to the streets of New York to measure public opinion, visits the birthplace of Shakespeare and, finally, looks at a production of Richard III’. The film includes interviews with actors such as Kenneth Branagh and Vanessa Redgrave and seeks to prove that everyone can enjoy Shakespeare, and that his tales are timeless and universal. The completion of the film marks the culmination of a journey begun decades ago. when Pacino was touring colleges in the late 70’s talking to students who were reluctant to listen to Shakespeare and couldn’t see the relevance of his works. “But we would talk informally about the play and then I would read an excerpt” explains Pacino. Pacino notes, “By juxtaposing the day-to-day life of the actors and their characters with ordinary people, we attempted to create a comic mosaic - a very different Shakespeare. -

“The Farcical Tragedies of King Richard III”: the Nineteenth-Century Burlesques

Theatre Survey (2021), 62,25–50 doi:10.1017/S0040557420000460 ARTICLE “The Farcical Tragedies of King Richard III”: The Nineteenth-Century Burlesques Nicoletta Caputo English Literature, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy Email: [email protected] Unlike other Shakespearean tragedies, King Richard III was never turned into a comedy through the insertion of a happy ending. It did, however, undergo a trans- formation of dramatic genre, as the numerous Richard III burlesques and travesties produced in the nineteenth century plainly show. Eight burlesques (or nine, includ- ing a pantomime) were written for and/or performed on the London stage alone.1 This essay looks at three of these plays, produced at three distinct stages in the his- tory of burlesque’s rapid rise and decline: 1823, 1844, and 1868. In focusing on these productions, I demonstrate how Shakespeare burlesques, paradoxically, enhanced rather than endangered the playwright’s iconic status. King Richard III is a perfect case study because of its peculiar stage history. As Richard Schoch has argued, the burlesque purported to be “an act of theatrical reform which aggres- sively compensated for the deficiencies of other people’s productions. [It] claimed to perform not Shakespeare’s debasement, but the ironic restoration of his compromised authority.”2 But this view of the burlesques’ importance is incom- plete. Building on Schoch’s work, I illustrate how the King Richard III burlesques not only parodied deficient theatrical productions but also called into question dra- matic adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays. In so doing, these burlesques paradoxi- cally relegitimized Shakespeare. Examining the burlesques of King Richard III is revealing in more than one respect. -

The Tragedy of King Richard III by William Shakespeare

1 Shakespeare – live The Tragedy of King Richard III by William Shakespeare Historical background The real-life Richard III was born in1485. He was Edward IV’s brother and Richard, Duke of York’s third son. Upon Edward’s death in 1483 he imprisoned his nephews in the Tower of London, announced that they had died there and proclaimed himself King of England. In 1485 Richard III was killed during the Battle of Bosworth Field, at the hand of Henry Tudor (Earl of 5 Richmond) who was later to become Henry VII. In the period after his death Richard was often portrayed negatively, attacked or defamed in literary and historical accounts, particularly Thomas More’s ‘History of Richard III’, which was also a source for Shakespeare’s play. Later historians have attempted to clear his name to some degree, notably Horace Walpole in his 10 ‘Historic Doubts on the Life and Death of Richard III’. However, Richard III remains one of the most controversial figures in English history. The play The Tragedy of King Richard III is considered a historical tragedy. After Hamlet, it is Shakespeare’s second longest drama and yet it is one of his most often performed plays. There are at least half a dozen film versions of the play, in which some of the stage’s best actors have played major roles. 15 The drama unfolds in five acts, beginning with the exposition and the complication of the plot within the first two acts. Typically, the climax comes at the end of Act III. The dénouement and the finale follow in the remaining two acts. -

Iowa State Journal of Research 56.1

IOWA STATE JOURNAL OF RESEARCH I MAY, 1982 4'3 -439 Vol. 56, No. 4 IOWA STATE JOURNAL OF RESEARCH TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 56 (August, 1981-May, 1982) No. 1, August, 1981 ASPECTS IN RENAISSANCE SCHOLARSHIP PAPERS PRESENTED AT "SHAKESPEARE AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES" SYMPOSIUM, 1981 From the Editors. 1 GALYON, L. R. Introduction...................... ...... 5 BEVINGTON, D. M. "Why Should Calamity Be Full of Words?" The Efficacy of Cursing in Richard III . 9 ANDERSON, D. K., Jr. The King's Two Rouses and Providential Revenge in Hamlet . 23 ONUSKA, J. T., Jr. Bringing Shakespeare's Characters Down to Earth: The Significance of Kneeling . 31 MULLIN, M. Catalogue-Index to Productions of the Shakespeare Memorial/Royal Shakespeare Theatre, 1879-1978 . 43 SCHAEFER, A. J. The Shape of the Supernatitral: Fuseli on Shakespeare. 49 POAGUE, L. "Reading" the Prince: Shakespeare, Welles, and Some Aspects of Chimes at Midnight . 57 KNIGHT, W. N. Equity in Shakespeare and His Contemporaries. 67 STATON, S. F. Female Transvestism in Renaissance Comedy: "A Natural Perspective, That Is and Is Not" . 79 IDE, R. S. Elizabethan Revenge Tragedy and the Providential Play-Within-a-Play. 91 STEIN, C.H. Justice and Revenge in The Spanish Tragedy... 97 * * * * * * * * * * No. 2, November, 1981 From the Editors.. ... 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS PUHL, J. Forearm liquid crystal thermograms during sustained and rhythmic handgrip contractions . 107 COUNTRYMAN, D. W. and D. P. KELLEY. Management of existing hardwood stands can be profitable for private woodland owners....... .... 119 MERTINS, C. T. and D. ISLEY. Charles E. Bessey: Botanist, educator, and protagonist . 131 HELSEL, D. B. -

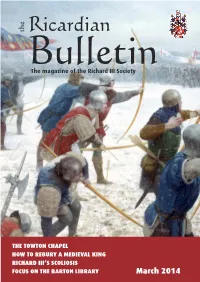

Ricardian Bulletin March 2014 Text Layout 1

the Ricardian Bulletin The magazine of the Richard III Society THE TOWTON CHAPEL HOW TO REBURY A MEDIEVAL KING RICHARD III’S SCOLIOSIS FOCUS ON THE BARTON LIBRARY March 2014 Advertisement the Ricardian Bulletin The magazine of the Richard III Society March 2014 Richard III Society Founded 1924 Contents www.richardiii.net 2 From the Chairman In the belief that many features of the tradi- 3 Reinterment news Annette Carson tional accounts of the character and career of 4 Members’ letters Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society 7 Society news and notices aims to promote in every possible way 12 Future Society events research into the life and times of Richard III, 14 Society reviews and to secure a reassessment of the material relating to this period and of the role in 16 Other news, reviews and events English history of this monarch. 18 Research news Patron 19 Richard III and the men who died in battle Lesley Boatwright, HRH The Duke of Gloucester KG, GCVO Moira Habberjam and Peter Hammond President 22 Looking for Richard – the follow-up Peter Hammond FSA 25 How to rebury a medieval king Alexandra Buckle Vice Presidents 37 The Man Himself: The scoliosis of Richard III Peter Stride, Haseeb John Audsley, Kitty Bristow, Moira Habberjam, Qureshi, Amin Masoumiganjgah and Clare Alexander Carolyn Hammond, Jonathan Hayes, Rob 39 Articles Smith. 39 The Third Plantagenet John Ashdown-Hill Executive Committee 40 William Hobbys Toni Mount Phil Stone (Chairman), Paul Foss, Melanie Hoskin, Gretel Jones, Marian Mitchell, Wendy 42 Not Richard de la Pole Frederick Hepburn Moorhen, Lynda Pidgeon, John Saunders, 44 Pudding Lane Productions Heather Falvey Anne Sutton, Richard Van Allen, 46 Some literary and historical approaches to Richard III with David Wells, Susan Wells, Geoffrey Wheeler, Stephen York references to Hungary Eva Burian 47 A series of remarkable ladies: 7. -

Trumbull, Connecticut SHAKESPEARE Grade 12 English Department 2017

TRUMBULL PUBLIC SCHOOLS Trumbull, Connecticut SHAKESPEARE Grade 12 English Department 2017 (Last revision date: 2000) Curriculum Writing Team Jessica Spillane English Department Chairperson, Trumbull High School Matthew Bracksieck English Teacher, Trumbull High School Jonathan S. Budd, Ph.D., Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum, Instruction, & Assessments Shakespeare Property of Trumbull Public Schools Shakespeare Grade 12 Table of Contents Core Values & Beliefs ............................................................................................... 2 Introduction & Philosophy ......................................................................................... 2 Course Goals ............................................................................................................... 3 Course Enduring Understandings ............................................................................... 6 Course Essential Questions ......................................................................................... 7 Course Knowledge & Skills........................................................................................ 7 Course Syllabus ......................................................................................................... 8 Unit 1: Introduction to Shakespeare – The Person and the Plays .............................. 10 Unit 2: The History Plays .......................................................................................... 14 Unit 3: The Comedy Plays ........................................................................................ -

Taming of the Shrew Study Guide

King Edward IV: King of England at the play’s Richard the Third beginning, Richard’s Performance Study Guide eldest brother. George, Duke of Compiled by Kristin Hall, M.A. Clarence: Brother The Atlanta Shakespeare Company to King Edward and at the New American Shakespeare Tavern Richard. Almost [email protected] always referred to as ‘Clarence.’ Imprisoned by King Edward after Richard frames him. Murdered. Original Practice and Playing Henry VI: He’s already been murdered by Richard Shakespeare at the play’s beginning, but we see his body taken to burial in Act I and his ghost appears to The Atlanta Shakespeare Company (ASC) at to Richard in Act V. the New American Shakespeare Tavern is Lady Anne: Dead Henry VI’s daughter-in-law. proud to call itself an ‘Original Practice’ Richard and King Edward also killed her company. In a nutshell, ‘Original Practice’ husband. She later becomes Queen after means the active exploration of the Richard seduces her. Presumably murdered. Elizabethan stagecraft and acting techniques Margaret: Henry VI’s widow, and thus the former that Shakespeare’s own audiences would Queen. While Queen she ordered the death of have enjoyed nearly four hundred years ago. Richard’s father and little brother. In return, he So what does this mean for an audience killed her husband and, with help from Edward, member at one of our Shakespeare her son. She resists exile to ‘slyly lurk’ and productions? You will see an exciting give ‘quick curses’ to members of the court. performance featuring period costumes, Queen Elizabeth: Edward’s Queen, whom he sword fights, actor-generated sound effects married despite the fact that she was not of rather than pre-recorded ones, and live suitable noble birth to be a Queen. -

The Hollow Crown: the Wars of the Roses

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 3 MAY 2016 The Hollow Crown: The Wars of the Roses Henry VI Part I, Henry VI Part II and Richard III Following 2012's critically acclaimed BAFTA winning first series, The Hollow Crown: The Wars of the Roses is the concluding part of an ambitious and thrilling cycle of Shakespeare's Histories filmed for BBC Two, comprising Henry VI Part I & II, and Richard III, and featuring the very best of British on-screen talent. A Neal Street Co-Production with Carnival / NBC Universal and Thirteen for BBC STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 3 MAY 2016 Synopses Henry VI Part I Henry V is dead, and against the backdrop of Wars in France the English nobles are beginning to quarrel. News of defeat at Orleans reaches the Duke of Gloucester, the Lord Protector, and other nobles in England. Henry VI, still an infant, is proclaimed King. Seventeen years later the rivalries at Court have intensified; Gloucester and the Bishop of Winchester argue openly in front of the King. Rouen falls to the French but Plantagenet, recently restored as the Duke of York, Exeter and Talbot pledge to recapture the city from the Dauphin. Battle commences and the French, led by Joan of Arc, defeat the English. Valiant Talbot and his son John are killed. Warwick and Somerset arrive after the battle to join forces with the survivors and retake Rouen. Somerset woos Margaret of Anjou as a potential bride for Henry VI. Plantagenet takes Joan of Arc prisoner and she is burnt at the stake. Gloucester protests but still Margaret is introduced as Henry's queen.