Autobiographical Writings by Wanda Rutkiewicz and Arlene Blum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya

The Himalaya by the Numbers A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya Richard Salisbury Elizabeth Hawley September 2007 Cover Photo: Annapurna South Face at sunrise (Richard Salisbury) © Copyright 2007 by Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley No portion of this book may be reproduced and/or redistributed without the written permission of the authors. 2 Contents Introduction . .5 Analysis of Climbing Activity . 9 Yearly Activity . 9 Regional Activity . .18 Seasonal Activity . .25 Activity by Age and Gender . 33 Activity by Citizenship . 33 Team Composition . 34 Expedition Results . 36 Ascent Analysis . 41 Ascents by Altitude Range . .41 Popular Peaks by Altitude Range . .43 Ascents by Climbing Season . .46 Ascents by Expedition Years . .50 Ascents by Age Groups . 55 Ascents by Citizenship . 60 Ascents by Gender . 62 Ascents by Team Composition . 66 Average Expedition Duration and Days to Summit . .70 Oxygen and the 8000ers . .76 Death Analysis . 81 Deaths by Peak Altitude Ranges . 81 Deaths on Popular Peaks . 84 Deadliest Peaks for Members . 86 Deadliest Peaks for Hired Personnel . 89 Deaths by Geographical Regions . .92 Deaths by Climbing Season . 93 Altitudes of Death . 96 Causes of Death . 97 Avalanche Deaths . 102 Deaths by Falling . 110 Deaths by Physiological Causes . .116 Deaths by Age Groups . 118 Deaths by Expedition Years . .120 Deaths by Citizenship . 121 Deaths by Gender . 123 Deaths by Team Composition . .125 Major Accidents . .129 Appendix A: Peak Summary . .135 Appendix B: Supplemental Charts and Tables . .147 3 4 Introduction The Himalayan Database, published by the American Alpine Club in 2004, is a compilation of records for all expeditions that have climbed in the Nepal Himalaya. -

Climbing on Kangchenjunga Since 1955

JOSE LUIS BERMUDEZ Climbing on Kangchenjunga since 1955 he history of climbing on Kangchenjunga in the years immediately T after the first ascent is easily told. Nothing happened for almost twenty years. There were many reasons for this. The sheer remoteness of the mountain must surely be one, as must the political difficulties in getting permission to climb the mountain either from Sikkim or from Nepal. And it is understandable that in the late 1950s the attention of mountaineers should have been focused on the 8000-metre peaks that were still unclimbed. Kangchenjunga's status as a holy mountain was a further obstacle. So it is not entirely surprising that there were no expeditions to the Kangchenjunga massif between 1955 and 1973. When climbers did eventually return to Kangchenjunga they found obvious and formidable challenges. Kangchenjunga has four distinct sum mits over 8000m. 1 The 1955 expedition climbed the Main Peak, which is the highest at 8586m. But that still left three virgin summits which were not much shorter: the South Summit at 8476m, the Central Summit at 8482m and the West Summit (better known as Yalung Kang) at 8505m. Equally significant were the two routes that had been attempted on the Main Peak before the successful expedition. The route taken by the first ascensionists was the Yalung (SW) Face, approached from the Yalung gla cier on the Nepalese side of the frontier ridge. As emerged very clearly in the Seminar, the Yalung Face was not the route favoured by most previous attempts on the mountain. The three expeditions in the late 1920s and early 1930s had thought that the North Ridge was the key to the mountain. -

Club Activities

Club Activities EDITEDBY FREDERICKO.JOHNSON A.A.C.. Cascade Section. The Cascade Section had an active year in 1979. Our Activities Committee organized a slide show by the well- known British climber Chris Bonington with over 700 people attending. A scheduled slide and movie presentation by Austrian Peter Habeler unfortunately was cancelled at the last minute owing to his illness. On-going activities during the spring included a continuation of the plan to replace old bolt belay and rappel anchors at Peshastin Pinnacles with new heavy-duty bolts. Peshastin Pinnacles is one of Washington’s best high-angle rock climbing areas and is used heavily in the spring and fall by climbers from the northwestern United States and Canada. Other spring activities included a pot-luck dinner and slides of the American Women’s Himalayan Expedition to Annapurna I by Joan Firey. In November Steve Swenson presented slides of his ascents of the Aiguille du Triolet, Les Droites, and the Grandes Jorasses in the Alps. At the annual banquet on December 7 special recognition was given to sec- tion members Jim Henriot, Lynn Buchanan, Ruth Mendenhall, Howard Stansbury, and Sean Rice for their contributions of time and energy to Club endeavors. The new chairman, John Mendenhall, was introduced, and a program of slides of the alpine-style ascent of Nuptse in the Nepal Himalaya was presented by Georges Bettembourg, followed by the film, Free Climb. Over 90 members and guests were in attendance. The Cascade Section Endowment Fund Committee succeeded in raising more than $5000 during 1979, to bring total donations to more than $12,000 with 42% of the members participating. -

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II Subject Page Afghanistan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 2 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 3 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 24 Culture Gram .......................................................... 30 Kazakhstan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 39 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 40 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 58 Culture Gram .......................................................... 62 Uzbekistan ................................................................. CIA Summary ......................................................... 67 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 68 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 86 Culture Gram .......................................................... 89 Tajikistan .................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 99 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 117 Culture Gram .......................................................... 121 AFGHANISTAN GOVERNMENT ECONOMY Chief of State Economic Overview President of the Islamic Republic of recovering -

The Boardman Tasker Prize 2011

The Boardman Tasker Prize 2011 Adjudication by Barry Imeson I would like to start by thanking my two distinguished co-judges, Lindsay Griffin and Bernard Newman, for ensuring that we have all arrived at this year’s award in good health and still on speaking terms. We met at the BMC on 9 September to agree a shortlist based on what, in our view, constituted ‘mountain literature’ and what also met the Award criterion of being an original work that made an outstanding contribution to mountain literature. We then considered the twenty three books that had been entered and, with no small difficulty, produced a shortlist of five. We would like to start with the non-shortlisted books. As judges we were conscious of the effort required to write a book and we want to thank all the authors who provided such a variety of enjoyable, and often thought-provoking, reads. We were, however, particularly impressed by two books, which though not shortlisted, we believe have made welcome additions to the history of mountaineering. The first of these was Prelude to Everest by Ian Mitchell & George Rodway. Their book sheds new light on the correspondence between Hinks and Collie and includes Kellas’s neglected 1920 paper A Consideration of the Possibility of Ascending Mount Everest. This is a long overdue and serious attempt to re-habilitate Kellas, a modest and self-effacing man. Kellas was an important mountaineer, whose ascent of Pauhunri in North East Sikkim was, at that time, the highest summit in the world trodden by man. His research into the effects of altitude on climbers was ahead of its time. -

Annapurna: a Womans Place Free

FREE ANNAPURNA: A WOMANS PLACE PDF Arlene Blum | 272 pages | 01 Oct 2015 | COUNTERPOINT | 9781619026032 | English | Berkeley, United States Annapurna: A Woman's Place by Arlene Blum, Paperback | Barnes & Noble® Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try Annapurna: A Womans Place. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Annapurna by Arlene Blum. Maurice Herzog Foreword by. Expedition leader Arlene Blum here tells their dramatic story: the logistical problems, storms, and hazardous ice climbing; the conflicts and reconciliations within the team; the terror of avalanches that threatened to sweep away camps and Annapurna: A Womans Place. On October 15, two women and two Sherpas at last stood on the summit—but the celebration was cut short, for two days later, the two women of the second summit team fell to their deaths. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published October 13th by Counterpoint first published More Details Original Title. Arlene Blum. Other Editions Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Annapurnaplease sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of Annapurna: A Woman's Place. A must read. First of all, it's Annapurna: A Womans Place top-notch outdoor adventure - a start to finish account of the journey to safely and smoothly place the first all-woman team atop Annapurna 1, a climb that was also the first successful American ascent. -

January 13, 2006, at the Dolphin Club, San Francisco

Chair: Lee Langan The Explorers Club 415 567-8089 [email protected] Vice Chair: Alan Nichols 415 789-9348 [email protected] Northern California Chapter Treasurer: Anders Jepsen 925 254-3079 December 2005 - January 2006 [email protected] Secretary: Stephen E. Smith Webmaster: Mike Diggles Newsletter: Lee Langan Web site: http://www.diggles.com/ec/ Douglas Capone a look at a tiny tough Doug’s Talk follows the population Ocean Film Festival Planet of the Reception Prokaryotes Doug Capone is inter- Here’s a film festival that celebrates the ested in microbial life joy, power, and mystery of the sea. Fol- in the world ocean. His lowing a successful debut in January research focuses on 2004, the San Francisco Ocean Film the marine microbes Festival (SFOFF) continues to build in the cycles of nitro- on its success, featuring documenta- gen and carbon, from ries and narrative works by filmmak- the fundamental ecology of marine ers from around the world who want to ecosystems and interactions with share their passion for the earth’s last environmental perturbations. frontier. Prokaryotes* are the original This unique festival had its pre- inhabitants of this planet. They miere January 10 and 11, 2004, at Fort are the toughest of the tough; they Mason’s Cowell Theater with films on hold all the records for living in the saltwater sports, oceanography, coastal coldest, hottest, driest, most acidic and snows. He has participated in over culture and more. Hundreds viewed most highly pressurized environments. thirty major oceanographic expeditions the beauty and mysteries of the ocean’s Also for the longest time! Come learn and has served as the chief scientist depths, experienced the thrill of ocean about these tiny creatures from the on over ten. -

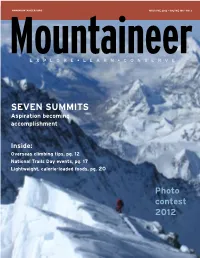

SEVEN SUMMITS Aspiration Becoming Accomplishment

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG MAY/JUNE 2012 • VOLUME 106 • NO. 3 MountaineerE X P L O R E • L E A R N • C O N S E R V E SEVEN SUMMITS Aspiration becoming accomplishment Inside: Overseas climbing tips, pg. 12 National Trails Day events, pg. 17 Lightweight, calorie-loaded foods, pg. 20 Photo contest 2012 inside May/June 2012 » Volume 106 » Number 3 12 Cllimbing Abroad 101 Enriching the community by helping people Planning your first climb abroad? Here are some tips explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest. 14 Outdoors: healthy for the economy A glance at the value of recreation and preservation 12 17 There is a trail in need calling you Help out on National Trails Day at one of these events 18 When you can’t hike, get on a bike Some dry destinations for National Bike Month 21 Achieving the Seven Summits Two Olympia Mountaineers share their experiences 8 conservation currents New Alpine Lakes stewards: Weed Watchers 18 10 reachING OUT Great people, volunteers and partners bring success 16 MEMbERShIP matters A hearty thanks to you, our members 17 stepping UP Swapping paddles for trail maintenance tools 24 impact GIVING 21 Mountain Workshops working their magic with youth 32 branchING OUT News from The Mountaineers Branches 46 bOOkMARkS New Mountaineers release: The Seven Summits 47 last word Be ready to receive the gifts of the outdoors the Mountaineer uses . DIscoVER THE MOUntaINEERS If you are thinking of joining—or have joined and aren’t sure where to start—why not attend an information meeting? Check the Branching Out section of the magazine (page 32) for times and locations for each of our seven branches. -

Harvard Mountaineering 31

HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING Number 31 JANUARY, 2 0 2 1 THE HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING CLUB CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING NUMBER 31 JANUARY, 2 0 2 1 THE HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING CLUB CAMBRIDGE, MASS. Photo, Vladislav Sevostianov To those who came before us and turned this affair of the soul into the best damned HMC we could imagine, and in whose steps we hope to follow. Photo, Nicolò Foppiani In Memoriam Mark Herzog August 22, 1992 – January 27, 2020 In Memoriam Photo, Kevin Ziechmann Janette Heung May 26, 1985 - September 5, 2020 Club Officers 2019 - 2020 2020 - 2021 President: ELISSA TAYLOR President: ELISSA TAYLOR Vice President: KYLE SUttON Vice President: JACK LAWLOR Secretary: GEnnIE WEILER Secretary: KYLE SUttON Treasurer: KAMI KRISTA Treasurer: PAUL GEORGOULIS Cabin Liaison: KEN PEARSON Librarian: ELI FRYDMAN Cabin Liaison: KEN PEARSON Gear Czar: JACK LAWLOR & Librarian: SERENA WURMSER LINCOLN CRAVEN- Gear Czar: CHARLIE BIggS & BRIGHTMAN CHRIS PARTRIDGE Graduate Liaison: NICOLÒ FOppIANI Graduate Liaison: NICOLÒ FOppIANI Faculty Advisor PROF. PAUL MOORCROft Journal Editor: SERENA WURMSER Copies of this and previous issues of HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING are available on request for $10.00 each from the Harvard Mountaineering Club; #73 SOCH; 59 Shepard st; Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA. Contents 2019 HMC BOLIVIA EXPEDITION ................................................................ 9 Eliza Ennis & Vladislav Sevostianov METEORA GREECE, AUGUST 2019 ................................................................ 15 Carson Denison CLIMBIng THE MAttERHORN WITH JANEttE: THE 2019 HMC .................... 34 TRIP TO THE ALPS Nicolò Foppiani TRAD BEFORE TRAD: LIFE AT THE GUnkS IN THE 1960S ................................... 42 Mark Van Baalen ICE ON MY AXES: PLAntIng SEASON IN THE HIMALAYAS, ICELAND, ........... 50 AND PATAGONIA Emin Aklik ALPINE ALTERNATIVES: THE HIGH TATRAS .................................................. -

ASIAN ALPINE E-NEWS Issue No 75. September 2020

ASIAN ALPINE E-NEWS Issue No 75. September 2020 C CONTENTS All-Afghan Team with two Women Climb Nation's Highest Peak Noshakh 7492m of Afghanistan Page 2 ~ 6 Himalayan Club E-Letter vol. 40 Page 7 ~ 43 1 All-Afghan Team, with 2 Women Climb Nation's Highest – Peak Noshakh 7492m The team members said they did their exercises for the trip in Panjshir, Salang and other places for one month ahead of their journey. Related News • Female 30K Cycling Race Starts in Afghanistan • Afghan Female Cyclist in France Prepares for Olympics Fatima Sultani, an 18-year-old Afghan woman, spoke to TOLOnews and said she and companions reached the summit of Noshakh in the Hindu Kush mountains, which is the highest peak in Afghanistan at 7,492 meters. 1 The group claims to be the first all-Afghan team to reach the summit. Fatima was joined by eight other mountaineers, including two girls and six men, on the 17-day journey. They began the challenging trip almost a month ago from Kabul. Noshakh is located in the Wakhan corridor in the northeastern province of Badakhshan. “Mountaineering is a strong sport, but we can conquer the summit if we are provided the gear,” Sultani said.The team members said they did their exercises for the trip in Panjshir, Salang and other places for one month ahead of their journey. “We made a plan with our friends to conquer Noshakh summit without foreign support as the first Afghan team,” said Ali Akbar Sakhi, head of the team. The mountaineers said their trip posed challenge but they overcame them. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

Writing the Ascent: Narrative and Mountaineering Accounts A thesis submitted to the Department of English Lakehead University Thunder Bay, ON In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in English By Justin Allec April, 2009 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49954-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49954-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Read Through the Information Below About K2 and the Climbers' Recent

What is happening in the news this week? A team of climbers from Nepal have become the first ever to summit the world’s second highest mountain, K2, in winter. When did you last challenge yourself? Learn more about this week’s story here. Watch this week’s useful video here. This week’s Virtual Assembly here. How does it make me feel? sad angry happy confused excited worried shocked afraid despondent aggrieved beaming addled animated agitated astonished alarmed disconsolate annoyed buoyant baffled elevated anxious astounded apprehensive dismal discontented cheery bemused enlivened apprehensive disconcerted daunted doleful disgruntled contented bewildered enthusiastic concerned distressed fearful downhearted distressed delighted disorientated exhilarated disquieted dumbfounded frantic forlorn exasperated enraptured indistinct exuberant distraught horrified horrified gloomy frustrated gleeful muddled thrilled distressed staggered petrified melancholic indignant glowing mystified disturbed startled terrified miserable offended joyful perplexed fretful stunned woeful outraged puzzled perturbed surprised wretched resentful troubled vexed uneasy Assembly Resource Read through the information below about K2 and the climbers’ recent ascent to the summit. What do you think would have been the hardest part of the climb? How do you think the climbers would have felt when they reached the summit? K2 Fact file • K2 is found on the China-Pakistan border. • It is the second highest mountain in the world at 8611m (28251ft). • Known as the Savage Mountain,