A Reconsideration of Jihād in the Gambia River Region, 1850–1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetics of Relationality: Mobility, Naming, and Sociability in Southeastern Senegal by Nikolas Sweet a Dissertation Submitte

The Poetics of Relationality: Mobility, Naming, and Sociability in Southeastern Senegal By Nikolas Sweet A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee Professor Judith Irvine, chair Associate Professor Michael Lempert Professor Mike McGovern Professor Barbra Meek Professor Derek Peterson Nikolas Sweet [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-3957-2888 © 2019 Nikolas Sweet This dissertation is dedicated to Doba and to the people of Taabe. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The field work conducted for this dissertation was made possible with generous support from the National Science Foundation’s Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant, the Wenner-Gren Foundation’s Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, the National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship Program, and the University of Michigan Rackham International Research Award. Many thanks also to the financial support from the following centers and institutes at the University of Michigan: The African Studies Center, the Department of Anthropology, Rackham Graduate School, the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies, the Mellon Institute, and the International Institute. I wish to thank Senegal’s Ministère de l'Education et de la Recherche for authorizing my research in Kédougou. I am deeply grateful to the West African Research Center (WARC) for hosting me as a scholar and providing me a welcoming center in Dakar. I would like to thank Mariane Wade, in particular, for her warmth and support during my intermittent stays in Dakar. This research can be seen as a decades-long interest in West Africa that began in the Peace Corps in 2006-2009. -

Gambia Parliamentary Elections, 6 April 2017

EUROPEAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION FINAL REPORT The GAMBIA National Assembly Elections 6 April 2017 European Union Election Observation Missions are independent from the European Union institutions.The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. EU Election Observation Mission to The Gambia 2017 Final Report National Assembly Elections – 6 April 2017 Page 1 of 68 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................................. 3 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... 4 II. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 9 III. POLITICAL BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................. 9 IV. LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ELECTORAL SYSTEM ................................................................................. 11 A. Universal and Regional Principles and Commitments ............................................................................. 11 B. Electoral Legislation ............................................................................................................................... -

An Ethnographic Study of Mystics, Spirits, and Animist Practices in Senegal Peter Balonon-Rosen SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2013 Out of this World: An Ethnographic Study of Mystics, Spirits, and Animist Practices in Senegal Peter Balonon-Rosen SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Balonon-Rosen, Peter, "Out of this World: An Ethnographic Study of Mystics, Spirits, and Animist Practices in Senegal" (2013). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1511. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1511 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Out of this World: An Ethnographic Study of Mystics, Spirits, and Animist Practices in Senegal Balonon-Rosen, Peter Academic Director: Diallo, Souleye Project Advisor: Diakhaté, Djiby Tufts University American Studies Major Africa, Senegal, Dakar “Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for National Identity and the Arts: Senegal, SIT Study Abroad, Spring 2013” Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Research Methods 5 Validating Findings 7 Ethical Issues 7 What is Animism? 8 Marabouts 9 Rabbs, Djinnes, and Ndepps 11 Sandiol and the Village of Ndiol 13 Gris-Gris 16 Animism in Dakar: An Examination of Taxis and Lutte 18 Taxis 18 Lutte 19 Relationship with Islam 21 Conclustion 22 Bibliogrpahy 24 Time Log 25 2 Abstract Although the overwhelming majority of Senegal’s inhabitants consider themselves Muslim, there are still many customs and behaviors throughout the country that derive from traditional animism. -

APR 21 1969 DENVER And

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PROJECT REPORT IR-LI-32 Liberian Investigations BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRY OF LIBERIA AND ADJACENT COUNTRIES by Donald H. Johnson APR 21 1969 DENVER and Richard W U. S. Geological Survey U. S. Geological Surve OPEN FILE REPORT This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for confornity with Geological Survey and has not been edited or reviewed conformity with Geological Survey standards or nomenclature Monrovia, Liberia January 1969 BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY CF THE GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRY CF LIBERIA AND ADJACENT COUNTRIES by Donald H. Johnson and Richard ".W. '^hite » * U. S. Geological Survey January 1S39 INTRODUCTION . -. This compilation represents an attempt to list, as nearly as possible, aU references pertaining to the geology and mineral industry'of Liberia, and to indicate those that are held by the library of the Liberian Geological Survey. The bibliography is a contribution of the Geological Exploration and Resource Appraisal program, a combined effort of the Government of Liberia and the United'States Agency for International Development, carried out jointly by the Liberian Geological Survey and the United States Geological Survey. The references were compiled from many sources, including the card catalog of the U. S. Geological Survey library in Washington, the holdings of the Liberian Geological Survey libraryy various published bibliographies, references cited by authors of publications dealing with Liberian geology, and chance encounters in the literature. The list is admittedly incomplete, and readers are requested to call additional references to the attention of the compilers. References to mining, metallurgy, and mineral economics involving Liberia have been included, as have papers dealing with physical geography,. -

O Kaabu E Os Seus Vizinhos: Uma Leitura Espacial E Histórica Explicativa De Conflitos Afro-Ásia, Núm

Afro-Ásia ISSN: 0002-0591 [email protected] Universidade Federal da Bahia Brasil Lopes, Carlos O Kaabu e os seus vizinhos: uma leitura espacial e histórica explicativa de conflitos Afro-Ásia, núm. 32, 2005, pp. 9-28 Universidade Federal da Bahia Bahía, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=77003201 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto O KAABU E OS SEUS VIZINHOS: UMA LEITURA ESPACIAL E HISTÓRICA EXPLICATIVA DE CONFLITOS Carlos Lopes* Introdução Na definição dada pelos geógrafos, o espaço pode ter três dimensões: uma, determinada por um sentido absoluto que é a coisa em si e é o espaço dos cartógrafos com longitudes e latitudes, ou quilômetros qua- drados; uma segunda, que liga este primeiro espaço com os objetivos que ativam as suas ligações e perspectivas; e, por fim, uma terceira que inter- preta as relações entre os objetos, e as relações multiplicadas que estes criam entre si. Por exemplo, um hectare no centro de uma cidade não tem a mesma dimensão assumida pelo mesmo espaço numa zona rural, pois este último não possui toda a complexidade das representatividades multi- plicadas. O paradigma atual pretende que sem uma organização do espaço não existe processo de mobilização das forças produtivas.1 A relação entre espaço e território é muito complexa, visto que o primeiro não tem a força de fixação do segundo. -

Road Travel Report: Senegal

ROAD TRAVEL REPORT: SENEGAL KNOW BEFORE YOU GO… Road crashes are the greatest danger to travelers in Dakar, especially at night. Traffic seems chaotic to many U.S. drivers, especially in Dakar. Driving defensively is strongly recommended. Be alert for cyclists, motorcyclists, pedestrians, livestock and animal-drawn carts in both urban and rural areas. The government is gradually upgrading existing roads and constructing new roads. Road crashes are one of the leading causes of injury and An average of 9,600 road crashes involving injury to death in Senegal. persons occur annually, almost half of which take place in urban areas. There are 42.7 fatalities per 10,000 vehicles in Senegal, compared to 1.9 in the United States and 1.4 in the United Kingdom. ROAD REALITIES DRIVER BEHAVIORS There are 15,000 km of roads in Senegal, of which 4, Drivers often drive aggressively, speed, tailgate, make 555 km are paved. About 28% of paved roads are in fair unexpected maneuvers, disregard road markings and to good condition. pass recklessly even in the face of oncoming traffic. Most roads are two-lane, narrow and lack shoulders. Many drivers do not obey road signs, traffic signals, or Paved roads linking major cities are generally in fair to other traffic rules. good condition for daytime travel. Night travel is risky Drivers commonly try to fit two or more lanes of traffic due to inadequate lighting, variable road conditions and into one lane. the many pedestrians and non-motorized vehicles sharing the roads. Drivers commonly drive on wider sidewalks. Be alert for motorcyclists and moped riders on narrow Secondary roads may be in poor condition, especially sidewalks. -

MYSTIC LEADER ©Christian Bobst Village of Keur Ndiaye Lo

SENEGAL MYSTIC LEADER ©Christian Bobst Village of Keur Ndiaye Lo. Disciples of the Baye Fall Dahira of Cheikh Seye Baye perform a religious ceremony, drumming, dancing and singing prayers. While in other countries fundamentalists may prohibit music, it is an integral part of the religious practice in Sufism. Sufism is a form of Islam practiced by the majority of the population of Senegal, where 95% of the country’s inhabitants are Muslim Based on the teachings of religious leader Amadou Bamba, who lived from the mid 19th century to the early 20th, Sufism preaches pacifism and the goal of attaining unity with God According to analysts of international politics, Sufism’s pacifist tradition is a factor that has helped Senegal avoid becoming a theatre of Islamist terror attacks Sufism also teaches tolerance. The role of women is valued, so much so that within a confraternity it is possible for a woman to become a spiritual leader, with the title of Muqaddam Sufism is not without its critics, who in the past have accused the Marabouts of taking advantage of their followers and of mafia-like practices, in addition to being responsible for the backwardness of the Senegalese economy In the courtyard of Cheikh Abdou Karim Mbacké’s palace, many expensive cars are parked. They are said to be gifts of his followers, among whom there are many rich Senegalese businessmen who live abroad. The Marabouts rank among the most influential men in Senegal: their followers see the wealth of thei religious leaders as a proof of their power and of their proximity to God. -

Slavery and Slaving in African History Sean Stilwell Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00134-3 - Slavery and Slaving in African History Sean Stilwell Index More information Index Abbas, Emir of Kano, 189 Trans-Atlantic slave trade and, 145 , Abeokuta, 103 166–167 Abiodun, Alafi n of Oyo, 115 , 118 Ahmadu, Seku, 56 Abomey, 113 , 151 , 169 Ajagbo, Alafi n of Oyo, 115 Afrikaners, 57 , 186 Akan, 47 , 146 , 148 Agaja, King of Dahomey, 115 , 151 Akwamu, 75 , 101 age grades, 78 , 82 , 123 Akyem, 147 agricultural estates, 56–57 , 111 , 133 , al Rahman, ‘Abd, Sultan of Dar Fur, 140 135 , 138–142 , 150 , 152 , 157–159 , al-Kanemi, Shehu, 110 162–164 , 166–168 , 171 , 190 Allada, 151 agricultural revolution, 32 , 35 , 61 Aloma, Idris, 104 agriculture, 33 , 38 Álvaro II, King of Kongo, 97 , 105 Akan and, 147 Angola, 190 , 191 Asante and, 149 Anlo, 75 Borno and, 139 slavery and, 75–76 Dahomey and, 152 , 168–169 Anti-slavery international, 212 Dar Fur and, 140 António, King of Kongo, 105 economy and, 133 Archinard, Louis, 182 expansion of, 35 Aro, 86 freed slaves and, 204 Asante, 20 , 48 , 51 , 101 , 114 , 122 , 148–151 , Hausa city states and, 140 153 , 162 , 167 , 187 , 203 Kingdom of Kongo and, 159 Austen, Ralph, 167 origins of slavery and, 36 Austin, Gareth, 130 Sennar and, 141 Awdaghust, 134 slavery and, 37 , 128–131 , 133 , 135–142 , Axum, 37 , 99 146 , 150 , 152 , 155–157 , 159–160 , 164 , 167–168 , 170–172 , 174 , 188 , Badi II, Sultan of Sennar, 141 191 , 198 Bagirmi, 105 Sokoto Caliphate and, 166 Balanta, 60 , 78 Songhay and, 135–136 Bamba, Amadu, 197 South Africa and, 154–155 Bambara, 139 -

Intra-Faith Dialogue in Mali What Role for Religious Actors in Managing Local Conflicts?

Intra-faith dialogue in Mali What role for religious actors in managing local conflicts? The jihadist groups that overran the north and imams, ulema, qur’anic masters and leaders of parts of central Mali in 2012 introduced a ver- Islamic associations. These actors were orga- sion of Islam that advocates the comprehen- nised into six platforms of religious actors sive enforcement of Sharia law. Despite the based in Gao, Timbuktu, Mopti, Taoudeni, Mé- crimes committed by these groups, some naka and Ségou. These platforms seek to communities perceive them as providers of se- contribute to easing intra-faith tensions, as well curity and equity in the application of justice. as to prevent and manage local conflicts, These jihadist influences have polarised com- whether communal or religious in nature. The munities and resulted in tensions between the examples below illustrate their work. diverse branches of Islam. Against this background, in 2015 the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) began facilitating intra-faith dialogue among nearly 200 local MOPTI Ending competitive recitals of the Quran For nearly 40 years, the young of religious actors in engaging gious leaders asked the talibés or religious students with the talibés. groups to suspend “Missou”, around Mopti have regularly which they agreed to do. The The platform identified around competed in duels to see who groups’ marabouts were relie- 30 recital groups, mostly in can give the most skilful reci- ved to see that other religious Socoura, Fotama, Mopti and tal of the Quran. Known as leaders shared their concerns Bandiagara, and began awar- “Missou”, these widespread about these duels and added eness-raising efforts with se- duels can gather up to 60 their support to the initiative. -

From the Chair

AASR-Newsletter 20 (November 2003) 1 Jacob Kehinde Olupona AASR-President FROM THE CHAIR In February 2004, AASR will meet in Ghana to deliberate on the West Afri- can situation and to examine the role of religion in the social and cultural transformation of the region. The meeting also culminates our efforts to convene meetings in the three major regions of AASR activity on the conti- nent - Southern, Eastern, and Western Africa. I trust and hope that a good number of you will come. There are several reasons why we choose the top- ic of religion and social transformation. First, there is an explosion of religi- ous organisations and movements in West Africa – especially Pentecostal and Charismatic churches, Islamic groups, and neo-traditional religious movements. This exponential increase is unprecedented in West African history. With large number of adherents comes also physical growth of de- nominations, mosques, and temples in West African urban centers. Remark- ably, many religious organizations command larger numbers of constituents than some popular West African politicians and political leaders command. However, during the last two decades a sobering rift has risen between unprecedented growth and the mobilisation of West African masses to de- velop social and cultural transformation comparable to this growth. West Africa is a region embedded in war, violence, and enormous economic ‘crises’ certainly requiring critical intervention. Participants at the conference will examine possible roles religion may play in tackling these issues, as much as how religion itself is impli- cated in these crises. We are delighted that many members of AASR in Af- rica, Europe, and the United States indicated strong interests in attending this significant regional meeting! While in Ghana, members will also deliberate on the future of AASR, especially as we prepare for the IAHR Congress in Japan. -

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center Is Launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center is launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal On February 27, 2015 the General Assembly for the formal establishment of the Integrated Economic and Social Development Center – CIDES Saloum of Kaolack’ Region was held within the premises of Kaolack’s Departmental Council. The event was chaired by the Minister of Women, Family and Child, by the Regional Governor and by the Mayors of the Department of Kaolack, Guinguinéo and Nioro. Amongst the participants were also the local authorities, senior representatives of the administrations and territorial services, representatives of undergoing programs, the Coordinator of the Ministry of Woman Unit for Poverty Reduction and representatives of the Italian Cooperation, plus all members of the CIDES Saloum. After opening words of the President of the Departmental Council of Kaolack, the Minister of Women on behalf of the President of the Republic recognized the efforts of all participants and the Government of Italy to support Senegal developmental policies. The Minister marked how CIDES represents a strategic tool for the development of territories and how it organically sets in the guidelines of Act III of the national decentralization policies. The event was led by a series of presentations and discussions on the results of the CIDES Saloum participatory design process, submission and approval of the Statute and the final election of members of its management structure. This event represents the successful completion of an action-research process developed over a year to design, through the active participation of local actors, the mission, strategic objectives and functions of Kaolack’s Integrated Center for Economic and Social Development. -

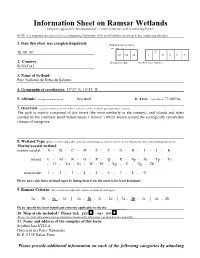

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. NOTE: It is important that you read the accompanying Explanatory Note and Guidelines document before completing this form. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY 18. 08. 92 S 03 04 84 1 E 0 0 3 2. Country: Designation date Site Reference Number SENEGAL 3. Name of wetland: Parc National du Delta du Saloum 4. Geographical coordinates: 13°37’ N, 16°42’ W 5. Altitude: (average and/or max. & min.) Sea level 6. Area: (in hectares) 73,000 ha 7. Overview: (general summary, in two or three sentences, of the wetland's principal characteristics) The park is mainly composed of dry forest (the most northerly in the country), and islands and islets created by the countless small watercourses (“bolons”) which weave around the ecologically remarkable clumps of mangrove. 8. Wetland Type (please circle the applicable codes for wetland types as listed in Annex I of the Explanatory Note and Guidelines document.) Marine/coastal wetland marine-coastal: A • B • C • D • E • F • G • H • I • J • K inland: L • M • N • O • P • Q • R • Sp • Ss • Tp • Ts • U • Va • Vt • W • Xf • Xp • Y • Zg • Zk man-made: 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 Please now rank these wetland types by listing them from the most to the least dominant: 9. Ramsar Criteria: (please circle the applicable criteria; see point 12, next page.) 1a • 1b • 1c • 1d │ 2a • 2b • 2c • 2d │ 3a • 3b • 3c │ 4a • 4b Please specify the most significant criterion applicable to the site: __________ 10.