4 Review of Cass Sunstein the SECOND BILL of RIGHTS.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“FDR's New Bill of Rights”

“FDR’s New Bill of Rights” Week 5 — Will Morrisey • William and Patricia LaMothe Professor in the U.S. Constitution Thoroughly educated in Progressive principles, Franklin D. Roosevelt believed that the task of statesmanship is to redefine our rights “in the terms of a changing and growing social order.” While the Founders thought the truths they celebrated in the Declaration of Independence were self-evident and so also timeless and unchanging, FDR argued for a new self-evident economic truth. His proposed “Economic Bill of Rights” lays out the means by which our new economic rights are to be secured, thereby achieving social equality and social justice. Lecture Summary In his 1944 Annual Message to Congress, FDR famously declared that the American people had accepted a “second Bill of Rights” that provided a new basis of security and prosperity for all. The original Bill of Rights—the first ten amendments to the Constitution, ratified by the American people—had been formulated in order to establish additional constitutional protections for the unalienable natural rights enunciated in the Declaration of Independence. (For example, Congress may not establish a religion; or abridge freedom of speech or of the press.) By contrast, in FDR’s view, the Constitution should be used as an instrument of progress. For FDR, the old doctrine of freedom of contract now should be understood as liberty within a social organization—a corporation, for example—which requires the protection of law against the evils which menace the health, safety, morals, and welfare of the people. Such protections become necessary because economic security and independence are prerequisites for true individual freedom: “Necessitous men are not free men.” FDR designed his “second Bill of Rights” to establish social equality as a fact by providing for the economic security and independence of individuals. -

Constitutionalism, Law & Politics II

Constitutionalism, Law & Politics II: American Constitutionalism POLS 30665 Fall 2016 Dr. Vincent Phillip Muñoz Mr. Raul Rodriguez – Teaching Assistant Department of Political Science University of Notre Dame “The conviction that there is a Creator God is what gave rise to the idea of human rights, the idea of the equality of all people before the law, the recognition of the inviolability of human dignity in every single person and the awareness of people’s responsibility for their actions. Our cultural memory is shaped by these rational insights. To ignore it or dismiss it as a thing of the past would be to dismember our culture totally and to rob it of its completeness.” - Pope Benedict XVI (2011) “A popular Government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or, perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance: And a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.” - James Madison, Letter to W. T. Barry (1822) “Every government degenerates when trusted to the rulers of the people alone. The people themselves, therefore, are its only safe depositories. And to render them safe, their minds must be improved to a certain degree." - Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (1782) "If a nation expects to be ignorant & free, in a state of civilisation, it expects what never was & never will be." - Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Charles Yancey (1816) “Conservative or liberal, we are all constitutionalists.” - Barack Obama, The Audacity of Hope (2006) In “Constitutionalism, Law & Politics II: American Constitutionalism” we shall attempt to understand the nature of the American regime and her most important principles. -

Is Over – Now What? Restoring the Four Freedoms As a Foundation for Peace and Security

The “War on Terror” Is Over – Now What? Restoring the Four Freedoms as a Foundation for Peace and Security Mark R. Shulman* As for our common defense, we reject as false the choice between our safety and our ideals. Our founding fathers, faced with perils that we can scarcely imagine, drafted a charter to assure the rule of law and the rights of man, a charter expanded by the blood of generations. Those ideals still light the world, and we will not give them up for expedience’s sake. And so, to all other peoples and governments who are watching today, from the grandest capitals to the small village where my father was born: know that America is a friend of each nation and every man, woman and child who seeks a future of peace and dignity, and we are ready to lead once more. – Barack H. Obama Inaugural Address, Jan. 20, 20091 The so-called “war on terror” has ended.2 By the end of his first week in office, President Barack H. Obama had begun the process of dismantling some of the most notorious “wartime” measures.3 A few weeks before, recently reappointed Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates had clearly forsaken the contentious label in a post-election essay on U.S. strategy in Foreign Affairs.4 Gates noted this historic shift in an almost offhanded * Assistant Dean for Graduate Programs and International Affairs and Adjunct Professor of Law at Pace University School of Law. A previous iteration of this article appeared in the Fordham Law Review. -

![American Political Thought [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3471/american-political-thought-pdf-1543471.webp)

American Political Thought [Pdf]

San José State University Department of Political Science POLS 163, American Political Thought, Spring 2021 Course and Contact Information Instructor: Kenneth B. Peter Office Location: Clark 449 Telephone: (408) 924-5562 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday 1:30-3:00 Wednesday 1030-1200 (email in advance to set up Zoom connection) Class Days/Time: Monday and Wednesday 9:00 – 10:15 Classroom: Synchronous online via Canvas ZOOM meetings Canvas learning management system Course materials can be found on the Canvas learning management system course website. You can learn how to access this site at this web address: http://www.sjsu.edu/at/ec/canvas/ Lectures on Zoom Lectures for this class will be provided live on Zoom. Zoom can be accessed from the course Canvas page. Students are expected to keep their cameras ON, to keep their microphones OFF except when asking questions, and to come in front of their computer as if they were coming to class on campus. This means dressing appropriately and devoting full attention to class. American Political Thought, Spring 2021 Page 1 of 21 Course Description Catalog description: 3 unit(s) Critical examination of the origins and development of American politics as seen through theorists, concepts and forces which have shaped American political consciousness. Grading: Graded Course description: Many of the political ideas which Americans take for granted were once new and controversial. This course seeks to reawaken the great debates which shaped our political heritage. American political theory is very different from the more famous tradition of European political theory. While APT has important European roots, it also reflects the unique historical and cultural circumstances of America. -

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Visionary Kloppenberg, James T

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Visionary Kloppenberg, James T. Reviews in American History, Volume 34, Number 4, December 2006, pp. 509-520 (Review) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/rah.2006.0062 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/rah/summary/v034/34.4kloppenberg.html Access Provided by Harvard University at 07/27/11 4:20PM GMT Franklin Delano roosevelt, visionary James t. kloppenberg elizabeth Borgwardt. A New Deal for the World: America’s Vision for Human Rights. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005. 437 pp. Notes, bibliography, illustrations, and index. $35.00. Cass r. sunstein. The Second Bill of Rights: FDR’s Unfinished Revolution and Why We Need It More than Ever. New York: Basic Books, 2004. vii + 294 pp. Notes, bibliography, and index. $25.00 (cloth); $16.95 (paper). Visitors to the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington D.C. find themselves face to face with FDR’s boldest challenge to the American people. Carved in the granite walls of the Memorial are the Four Freedoms that FDR proclaimed in January 1941. Joined to the Freedom of Speech and Freedom of Worship guaranteed by the original Bill of Rights are two new freedoms to be secured by Americans then confronting new dangers, Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear. The two books under review address the history and significance of those latter freedoms, which remain as elusive in 2006 as they were sixty-five years ago. Most Americans today, lulled into smug contentment with their role as consumers rather than citizens, and provoked by endless harangues into demonizing a shadowy and little understood enemy, seem as determined not to confront the reasons behind the problems of want and fear as FDR was determined to force the nation to face them. -

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness Instructor Answer Guide Chapter 12: 1932-1945

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness Instructor Answer Guide Chapter 12: 1932-1945 Contents CHAPTER 12 INTRODUCTORY ESSAY: 1932–1945 ............................................ 2 NARRATIVES .............................................................................................................. 4 The Dust Bowl ......................................................................................................................................... 4 The National Recovery Administration and the Schechter Brothers .................................................. 5 New Deal Critics ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Labor Upheaval, Industrial Organization, and the Rise of the CIO .................................................... 7 Court Packing and Constitutional Revolution ....................................................................................... 9 Eleanor Roosevelt and Marian Anderson ............................................................................................ 10 Foreign Policy in the 1930s: From Neutrality to Involvement ........................................................... 11 Pearl Harbor .......................................................................................................................................... 12 Double V for Victory: The Effort to Integrate the U.S. Military ........................................................ 14 D-Day ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Table of Contents

Journal of Working-Class Studies Volume 5 Issue 2, October 2020 Table of Contents Editorial Sarah Attfield and Liz Giuffre Article Obligations to the Future Lawrence M. Eppard, Erik Nelson, Cynthia Cox, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva Review Essay Not Just ‘Rosie the Riveter’: Feature Films and Productive Industrial Work Gloria McMillan Tribute Tribute to Florence Howe (March 17, 1929—September 12, 2020) Janet Zandy 1 Journal of Working-Class Studies Volume 5 Issue 2, October 2020 Volume 5 Issue 2: Editorial – Special ‘Mini’ Issue for 2020 U.S. Election Sarah Attfield, University of Technology Sydney Liz Giuffre, University of Technology Sydney This special mini-issue of the Journal of Working-Class Studies is intended to provide some ideas to consider prior and after, the 2020 U.S. Presidential election. While it might be the case that by time of publication, the American people will have already made up their minds, or cast their early votes, the pieces included here are intended to provide some opportunities to reflect on what has happened in the past, and what needs to happen in the future to improve the lives of working-class Americans. The ‘working-class Americans’ we refer to here are diverse in terms of race, gender, sexuality, ability, religion and immigration status. They are the retail and fast food workers, the factory and warehouse workers. These working-class Americans take care of the nations’ children and the elderly. They drive school buses and work in kindergartens. They work in care homes and hospitals. They are first responders and utility workers. Working-class Americans keep the streets clean and the roads and railways maintained. -

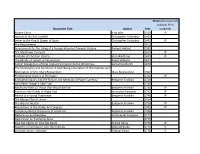

Document Title Author Year Status (S-Tentatively Seleced; IP-In Progress) Magna Carta King John 1215 IP Journal of the First

Status (S-tentatively seleced; IP-in Document Title Author Year progress) Magna Carta King John 1215 IP Journal of the first Landfall Christopher Columbus 1492 Letter to the King & Queen of Spain Christopher Columbus 1492 IP The Requirement 1513 Inducements for the Liking of a Voyage Intended Towards Virginia Richard Hakluyt 1585 The Mayflower Compact 1620 IP A Model of Christian Charity John Winthrop 1630 IP The Bloody of Tenent of Persecution Roger Williams 1644 A Brief Recognition of New-England’s Errand into the Wilderness Samuel Danforth 1670 The Sovereignty and Goodness of God: Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson Mary Rowlandson 1682 Pennsylvania Charter of Privileges 1701 IP A Modest Enquiry into the Nature and Necessity of Paper Currency Benjamin Franklin 1729 John Peter Zenger's Libel Trial 1735 Necessary Hints to Those That Would be Rich Benjamin Franklin 1736 IP Sinners in the Hands of Angry God Johnathan Edwards 1741 IP Advice to a Young Tradesman Benjamin Franklin 1748 IP The Albany Plan of Union 1754 The Way to Wealth Benjamin Franklin 1758 IP Resolutions of the Stamp Act Congress 1765 IP Testimony Before the House of Commons Benjamin Franklin 1766 Declaration and Resolves Continental Congress 1774 Declaration on Taking Up Arms 1775 Give Me Liberty Or Give Me Death Patrick Henry 1775 IP Speech on Conciliation with the Colonies Edmund Burke 1775 S Common Sense , selection Thomas Paine 1776 S Status (S-tentatively seleced; IP-in Document Title Author Year progress) Declaration of Independence Thomas Jefferson 1776 IP Letter to John Adams Abigail Adams 1776 S Virginia Constitution 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights 1776 Articles of Confederation 1777 S A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge Thomas Jefferson 1779 S Sentiments of an American Woman Esther Reed 1780 Hector St. -

Expansive Rights: FDR's Proposed “Economic” Bill of Rights

Expansive Rights: FDR’s Proposed “Economic” Bill of Rights Memorialized in the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, But with Little Impact in the United States Patrick J. Austin* Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 FDR’s Inspiration for the Economic Bill of Rights ............................................... 4 Rights or Principles? Determining the Driving Force Behind FDR’s Economic Bill of Rights .......................................................................................................... 6 The Rooseveltian Influence on the ICESCR ......................................................... 7 Similarities Between FDR’s Economic Bill of Rights and the ICESCR ............... 9 Differences Between FDR’s Economic Bill of Rights and the ICESCR ............. 11 Comparing the ICESCR and the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights ................... 13 Comparing the Economic Bill of Rights and the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights ................................................................................................................... 13 Why the Economic Bill of Rights is Not Law ..................................................... 16 Not a Complete Failure: Portions of the Economic Bill of Rights are Law ........ 17 A Moment to Speculate: What the United States Would Look Like if FDR’s Economic Bill of Rights were Enacted in 1944 ................................................... 18 Like -

The "War on Terror" Is Over--Now What? Restoring the Four Freedoms As a Foundation for Peace and Security

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2009 The "War on Terror" is Over--Now What? Restoring the Four Freedoms as a Foundation for Peace and Security Mark R. Shulman Pace Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the International Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Shulman, Mark R., "The "War on Terror" is Over--Now What? Restoring the Four Freedoms as a Foundation for Peace and Security" (2009). Pace Law Faculty Publications. 564. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/564 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The “War on Terror” is Over – Now What? Restoring the Four Freedoms as a Foundation for Peace and Security Mark R. Shulman* As for our common defense, we reject as false the choice between our safety and our ideals. Our founding fathers faced with perils that we can scarcely imagine, drafted a charter to assure the rule of law and the rights of man, a charter expanded by the blood of generations. Those ideals still light the world, and we will not give them up for expedience’s sake. And so, to all other peoples and governments who are watching today, from the grandest capitals to the small village where my father was born: know that America is a friend of each nation and every man, woman and child who seeks a future of peace and dignity, and we are ready to lead once more. -

A Visual and Textual Analysis of Transnational Identity Formation and Representation

CHAPMAN, DANIEL E., Ph.D. A Visual and Textual Analysis of Transnational Identity Formation and Representation. (2007) Directed by Dr. Leila E. Villaverde. 203 pp. This dissertation is an exploration of identity formation when crossing national boundaries and confronting disparate cultures and histories. Working with the assumption that identifying (or not) with local discourses informs behaviors and values, this study examines what questions emerge when one is immersed in discourses that were created beyond one’s locality. Through weekly interviews with two exchange students who came to the University of North Carolina at Greensboro from Mexico, this inquiry explores how they situate themselves within and against their local discourses before, during and after the transnational experience. The author uses bricolage and brings together different ways of knowing: visual, textual, historical, personal, and analytical in order to explore this encounter with difference. Crossing national boundaries is an experience in which fixed notions are called into question through exposure to disharmonious realities. The purpose of using bricolage is to expose the readers to disharmony in hopes that their own questions emerge about the representation of culture and nature. Rather than leading the reader down a path in which an argument is built vertically, bricolage immerses the reader into a conversation and encourages the reader to make his or her own meaning in their engagement with the texts. By exploring the students’ experiences through both a visual documentary and a textual discourse analysis, a comparison between the different forms of representation arises. Different questions and meanings emerge depending on which method the researcher is using. -

Constitutive Commitments and Roosevelt's Second Bill of Rights: a Dialogue

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2005 Constitutive Commitments and Roosevelt's Second Bill of Rights: A Dialogue Randy E. Barnett Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Cass R. Sunstein Harvard Law School This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/35 53 Drake L. Rev. 205-229 (2005) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons GEORGETOWN LAW Faculty Publications January 2010 Constitutive Commitments and Roosevelt's Second Bill of Rights: A Dialogue 53 Drake L. Rev. 205-229 (2005) Randy E. Barnett Cass R. Sunstein Professor of Law Professor of Law Georgetown University Law Center Harvard Law [email protected] [email protected] This paper can be downloaded without charge from: Scholarly Commons: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/35/ Posted with permission of the author CONSTITUTIVE COMMITMENTS AND ROOSEVELT'S SECOND BILL OF RIGHTS: A DIALOGUE Cass R. Sunstein* & Randy E. Barnett** TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Sunstein: Roosevelt's Second Bill of Rights ................................. 205 II. Sunstein: Constitutive Commitments ............................................ 217 III. Barnett: Taking "Constitutive Commitments" Seriously ........... 218 IV. Sunstein: Taking FDR Seriously .................................................... 221 V. Barnett: Why Do "Constitutive Commitments" Matter? ........... 222 VI. Sunstein: FDR's Incomplete Success ............................................. 223 VII. Barnett: Constitutive Commitments Do Not Matter, But If They Do ......................................................................................... 224 1. ROOSEVELT'S SECOND BILL OF RIGHTS! Cass R. Sunstein On January 11, 1944, the United States was involved in its longest conflict since the Civil War.