Polyamorous Relationships and Family Law in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INFORMATION BULLETIN June 2012 New Family Law

INFORMATION BULLETIN June 2012 New Family Law Act Table of Contents I. Background 3 II. Importance of Family Law to Women Who Are Victims of Violence in Relationships 5 III. Significant Changes in the Family Law Act for Women Who are Victims of Violence in Relationships 5 IV. Overview of Key Provisions Related to Family Violence 6 FLA Part 1 – Definitions 6 FLA Part 2 – Resolution of Family Law Disputes 7 FLA Part 4 – Care and Time with Children 7 FLA Part 7 – Child and Spousal Support 11 FLA Part 9 – Protection from Family Violence 11 FLA Part 10 – Court Processes 16 FLA Part 12 – Regulations 18 FLA Part 13 – Transitional Provisions 19 FLA Part 14 — Repeals, Related Amendment and 19 Consequential Amendments V. Implementation Issues 20 VI. Conclusion 21 VII. References 23 New Family Law Act Implications for Anti-Violence Workers, June 2012 2 INFORMATION BULLETIN June 2012 New Family Law Act Implications for Anti-Violence Workers1 The new provincial Family Law Act (FLA) received Royal Assent on November 24, 2011, fundamentally altering the way family law matters will be handled in BC. The new Act contains important and far reaching provisions intended to provide better protection for women and children experiencing violence in the family context. While the FLA has now passed through the legislature, most of its sections will not come into force until a regulation to this effect is enacted by Cabinet. The BC Ministry of Justice has announced that this will take place on March 18, 2013. This Information Bulletin will provide an overview of the changes to family law contained in the FLA. -

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

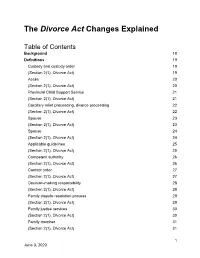

The Divorce Act Changes Explained

The Divorce Act Changes Explained Table of Contents Background 18 Definitions 19 Custody and custody order 19 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 19 Accès 20 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 20 Provincial Child Support Service 21 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 21 Corollary relief proceeding, divorce proceeding 22 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 22 Spouse 23 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 23 Spouse 24 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 24 Applicable guidelines 25 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 25 Competent authority 26 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 26 Contact order 27 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 27 Decision-making responsibility 28 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 28 Family dispute resolution process 29 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 29 Family justice services 30 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 30 Family member 31 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 31 1 June 3, 2020 Family violence 32 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 32 Legal adviser 35 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 35 Order assignee 36 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 36 Parenting order 37 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 37 Parenting time 38 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 38 Relocation 39 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 39 Jurisdiction 40 Two proceedings commenced on different days 40 (Sections 3(2), 4(2), 5(2) Divorce Act) 40 Two proceedings commenced on same day 43 (Sections 3(3), 4(3), 5(3) Divorce Act) 43 Transfer of proceeding if parenting order applied for 47 (Section 6(1) and (2) Divorce Act) 47 Jurisdiction – application for contact order 49 (Section 6.1(1), Divorce Act) 49 Jurisdiction — no pending variation proceeding 50 (Section 6.1(2), Divorce Act) -

How Understanding the Aboriginal Kinship System Can Inform Better

How understanding the Aboriginal Kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory Submitted by KAREN CHRISTINE KING BSW A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Social Work Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University December 2011 2 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee. Karen Christine King BSW 9th March 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT This qualitative inquiry explored the kinship system of both the Larrakia and Warumungu peoples of the Northern Territory with the aim of informing social work theory and practice in Australia. It also aimed to return information to the knowledge holders for the purposes of strengthening Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing. This study is presented as a journey, with the oral story-telling traditions of the Larrakia and Warumungu embedded and laced throughout. The kinship system is unpacked in detail, and knowledge holders explain its benefits in their lives along with their support for sharing this knowledge with social workers. -

Family Law (Guardianship of Minors, Domicile and Maintenance) Act

LAWS OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO MINISTRY OF LEGAL AFFAIRS www.legalaffairs.gov.tt FAMILY LAW (GUARDIANSHIP OF MINORS, DOMICILE AND MAINTENANCE) ACT CHAPTER 46:08 Act 15 of 1981 Amended by 20 of 1985 *14 of 1988 104 of 1994 28 of 1995 66 of 2000 *See Note on page 2 Current Authorised Pages Pages Authorised (inclusive) by L.R.O. 1–70 .. 1/2006 L.R.O. 1/2006 UPDATED TO DECEMBER 31ST 2009 LAWS OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO MINISTRY OF LEGAL AFFAIRS www.legalaffairs.gov.tt Family Law (Guardianship of Minors, 2 Chap. 46:08 Domicile and Maintenance) Index of Subsidiary Legislation Page Maintenance Rules (LN 89/1983) … … … … … 40 Note on Act No. 14 of 1988 For an order under section 13(2), 13(5), 13(6)(a), 13(6)(b), 14(1)(b), and 15(b), see paragraph 3 of Schedule 1 to the Attachment of Earnings (Amendment) Act, 1988 (Act No. 14 of 1988). Note on section 13 Orders for Custody and Maintenance For an order for custody and maintenance on the application of a parent under section 13 of the Act see Order 86 of the Rules of the Supreme Court (1975) which is inserted as an Appendix to this Act. UPDATED TO DECEMBER 31ST 2009 LAWS OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO MINISTRY OF LEGAL AFFAIRS www.legalaffairs.gov.tt Family Law (Guardianship of Minors, Domicile and Maintenance) Chap. 46:08 3 CHAPTER 46:08 FAMILY LAW (GUARDIANSHIP OF MINORS, DOMICILE AND MAINTENANCE) ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS SECTION 1. Short title. 2. Interpretation. GENERAL PRINCIPLES 3. -

Support and Property Rights of the Putative Spouse Florence J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 24 | Issue 2 Article 6 1-1973 Support and Property Rights of the Putative Spouse Florence J. Luther Charles W. Luther Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Florence J. Luther and Charles W. Luther, Support and Property Rights of the Putative Spouse, 24 Hastings L.J. 311 (1973). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol24/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Support And Property Rights Of The Putative Spouse By FLORENCE J. LUTHER* and CHARLES W. LUTHER** Orequire a "non-husband" to divide his assets with and to pay support to a "non-wife" may, at first glance, appear doctrinaire. How- ever, to those familiar with the putative spouse doctrine as it had de- veloped in California the concept should not be too disquieting. In 1969 the California legislature enacted Civil Code sections 4452 and 4455 which respectively authorize a division of property1 and perma- nent supportF to be paid to a putative spouse upon a judgment of an- nulment.' Prior to the enactment of these sections, a putative spouse in California was given an equitable right to a division of jointly ac- quired property,4 but could not recover permanent support upon the termination of the putative relationship.5 This article considers the ef- fect of these newly enacted sections on the traditional rights of a puta- tive spouse to share in a division of property and to recover in quasi- contract for the reasonable value of services rendered during the puta- * Professor of Law, University of the Pacific, McGeorge School of Law. -

All in the Family: Attitudes Towards Cousin Marriages Among Young Dutch People from Various Ethnic Groups

Original Evolution, Mind and Behaviour 15(2017), 1–15 article DOI: 10.1556/2050.2017.0001 ALL IN THE FAMILY: ATTITUDES TOWARDS COUSIN MARRIAGES AMONG YOUNG DUTCH PEOPLE FROM VARIOUS ETHNIC GROUPS ABRAHAM P. BUUNK* Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, The Hague and University of Groningen, The Netherlands (Received: 11 August 2016; accepted: 01 February 2017) Abstract. The present research examined attitudes towards cousin marriages among young people from various ethnic groups living in The Netherlands. The sample consisted of 245 participants, with a mean age of 21, and included 107 Dutch, 69 Moroccans, and 69 Turks. The parents of the latter two groups came from countries where cousin marriages are accepted. Participants reported more negative than positive attitudes towards cousin marriage, and women reported more negative attitudes than did men. The main objection against marrying a cousin was that it is wrong for religious reasons, whereas the risk of genetic defects was considered less important. Moroccans had less negative attitudes than both the Dutch and the Turks, who did not differ from each other. Among Turks as well as among Moroccans, a more positive attitude towards cousin marriage was predicted independently by a preference for parental control of mate choice and religiosity. This was not the case among the Dutch. Discussion focuses upon the differences between Turks and Moroccans, on the role of parental control of mate choice and religiosity, and on the role of incest avoidance underlying attitudes towards cousin marriage. Keywords: cousin marriage, consanguineity, Turks, Moroccans ATTITUDES TOWARDS COUSIN MARRIAGE The large cultural and historical variation in the attitudes towards cousin marriages suggests that there is not a universal, evolved mechanism against mating with cousins (cf. -

Committee of Experts on Family Law (Cj-Fa)

Strasbourg, 21 September 2009 CJ-FA (2008) 5 [cj-fa/cj-fa plenary meetings/38 th plenary meeting/working documents/cj-fa(2008) 5e] COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON FAMILY LAW (CJ-FA) A STUDY INTO THE RIGHTS AND LEGAL STATUS OF CHILDREN BEING BROUGHT UP IN VARIOUS FORMS OF MARITAL OR NON-MARITAL PARTNERSHIPS AND COHABITATION A Report for the attention of the Committee of Experts on Family Law by Nigel Lowe Professor of Law and Director of the Centre for International Family Law Studies Cardiff Law School, Cardiff University, United Kingdom Document prepared by the Secretariat of the Directorate General of Human Rights and Legal Affairs The views expressed in this publication are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the Council of Europe. I. TERMS OF REFERENCE AND FORM OF REPORT The basic terms of reference of this report are: • to undertake an investigative study into the rights and legal status of children being brought up in various forms of marital or non-marital partnership and cohabitation; • to make proposals concerning a possible follow-up. An important backdrop to this study is the existence of: 1. certain Council of Europe instruments, namely, the 1975 European Convention on the Legal Status of Children Born Out of Wedlock , which has long been recognised as in need of modernising, 1 and the not unrelated Recommendation No R (84) 4 on Parental Responsibilities and the “White Paper” On Principles Concerning the Establishment and Legal Consequences of Parentage ,2 which has not yet been followed up; and 2. human rights instruments, in particular the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 (“CRC”), to which all Council of Europe Member States are Parties, and by which State Parties are enjoined 3 to respect and ensure the Convention rights for each child within their jurisdiction are applied without discrimination of any kind . -

An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies

11 Close–Distant: An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies Abstract This chapter looks at the evidence for the close–distant dichotomy in the kinship systems of Australian Aboriginal societies. The close– distant dichotomy operates on two levels. It is the distinction familiar to Westerners from their own culture between close and distant relatives: those we have frequent contact with as opposed to those we know about but rarely, or never, see. In Aboriginal societies, there is a further distinction: those with whom we share our quotidian existence, and those who live at some physical distance, with whom we feel a social and cultural commonality, but also a decided sense of difference. This chapter gathers a substantial body of evidence to indicate that distance, both physical and genealogical, is a conception intrinsic to the Indigenous understanding of the function and purpose of kinship systems. Having done so, it explores the implications of the close–distant dichotomy for the understanding of pre-European Aboriginal societies in general—in other words: if the dichotomy is a key factor in how Indigenes structure their society, what does it say about the limits and integrity of the societies that employ that kinship system? 363 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN Introduction Kinship is synonymous with anthropology. Morgan’s (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family is one of the founding documents of the discipline. It also has an immediate connection to Australia: one of the first fieldworkers to assist Morgan in gathering his data was Lorimer Fison, who, later joined by A. -

The Idea of Virtue in Architecture

17-9-2012 the Theme 2 Craftsmanship: Intelligence and Making, the idea of love in architecture jctv argument Wanda Landowska’s hand in experiential terms words are rather poor In what ways do we capture experience? Pictures and words and all that.. Chengde, Hebei Province, Pule Si Fan Kuan 1000-1031, Travellers Among Streams and Mountains 1 17-9-2012 Tung Chi’i Chang: “Painting is no Someone with a small vocabulary equal to mountains and water for has a small capacity for expressing the wonder of scenery, but his experience in words and a small mountains and water are no equal capacity for processing and to painting for the sheer marvels of nuancing that experience. brush and ink”[1] Someone with a university But this means very little. He is still education, according to research capable of having that experience… done in1995 article has an average vocabulary of 8000 words… He can describe every and any experience, perception, feeling but With this he is able to describe and only on the basis of a selective process his experience. This means process: he selects for his he can only describe his experience description what he finds selectively important and what he has words for 2 17-9-2012 What you cannot capture in words, The whole of his experience is still remains part of your always larger and yet his experience. What does this mean? description is also richer than the It does not mean that words are experience itself, it is received in useless, it means that words the context of the receiver’s cannot be expected to capture experience and appropriated everything of bodily experience. -

Private Law As Constitutional Context for Same-Sex Marriage

Private Law as Constitutional Context for Same-sex Marriage Private Law as Constitutional Context for Same-sex Marriage ROBERT LECKEY * While scholars of gay and lesbian activism have long eyed developments in Canada, the leading Canadian judgment on same-sex marriage has recently been catapulted into the field of vision of comparative constitutionalists indifferent to gay rights and matrimonial matters more generally. In his irate dissent in the case striking down a state sodomy law as unconstitutional, Scalia J of the United States Supreme Court mentions Halpern v Canada (Attorney General).1 Admittedly, he casts it in an unfavourable light, presenting it as a caution against the recklessness of taking constitutional protection of homosexuals too far.2 Still, one senses from at least the American literature that there can be no higher honour for a provincial judgment from Canada — if only in the jurisdictional sense — than such lofty acknowledgement that it exists. It seems fair, then, to scrutinise academic responses to the case for broader insights. And it will instantly be recognised that the Canadian judgment emerged against a backdrop of rapid change in the legislative and judicial treatment of same-sex couples in most Western jurisdictions. Following such scrutiny, this paper detects a lesson for comparative constitutional law in the scholarly treatment of the recognition of same-sex marriage in Canada. Its case study reveals a worrisome inclination to regard constitutional law, especially the judicial interpretation of entrenched rights, as an enterprise autonomous from a jurisdiction’s private law. Due respect accorded to calls for comparative constitutionalism to become interdisciplinary, comparatists would do well to attend,intra disciplinarily, to private law’s effects upon constitutional interpretation. -

CHILD SUPPORT: by JUDICIAL DECISION by LEGISLATION? (Pt

REFORM OF THE LAW CHILD SUPPORT: BY JUDICIAL DECISION BY LEGISLATION? (Pt. I) Alastair Dissett-Johnson* Dundee This isa two-partarticle. Partone analyses the recent Supreme Court ofCanada decision in Willick and the Provincial Appeal Court decisions in L6vesque and Edwards on the issue ofassessing child support. Part two examines the British Child Support Acts 1991-5, which introduced an administrative formula driven method ofassessing child support, and the Canadian Federal/Provincial Family Law Committees Report Recommendations on Child Support. The merits and problems associated with administrative andjudicial methods ofassessing child support are examined and contrasted. Il s'agit d'un article en deux parties. La première partie analyse la décision récente de la Cour suprême du Canada dans l'affaire Willick, ainsi que les décisions de la Cour d'appelprovinciale dans les affaires Lévesque etEdward qui évaluent laprotection sociale de l'enfant. La secondepartie examine, d'unepart, les Child Support Acts britanniques (Lois sur la protection sociale de l'enfant) votées de 1991 à 1995 et quiontintroduit des moyens administratifs, basés surune formule, permettant d'évaluer laprotection sociale de l'enfant et, d'autre part, le Rapport des comités sur la législationfamilialefédérale/provinciale canadienne et les recommandations concernant la protection sociale de l'enfant. Les aspects positifs et négatifsliésaux méthodesadministratives etjudiciairesd'évaluation de la protection sociale de l'enfant sont examinés. I. Introduction .... ........