The Wolfram Mine at Wilks Creek, Victoria by PETER S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rivers Monitoring and Evaluation Plan V1.0 2020

i Rivers Monitoring and Evaluation Plan V1.0 2020 Contents Acknowledgement to Country ................................................................................................ 1 Contributors ........................................................................................................................... 1 Abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 Background and context ........................................................................................................ 3 About the Rivers MEP ............................................................................................................. 7 Part A: PERFORMANCE OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................... 18 Habitat ................................................................................................................................. 24 Vegetation ............................................................................................................................ 29 Engaged communities .......................................................................................................... 45 Community places ................................................................................................................ 54 Water for the environment .................................................................................................. -

Post-Fire Dynamics of Cool Temperate Rainforest in the O'shannassy Catchment

Post-fire dynamics of Cool Temperate Rainforest in the O’Shannassy Catchment A. Tolsma, R. Hale, G. Sutter and M. Kohout July 2019 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 298 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning PO Box 137 Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Phone (03) 9450 8600 Website: www.ari.vic.gov.au Citation: Tolsma, A., Hale, R., Sutter, G. and Kohout, M. (2019). Post-fire dynamics of Cool Temperate Rainforest in the O’Shannassy Catchment. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 298. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Heidelberg, Victoria. Front cover photo: Small stand of Cool Temperate Rainforest grading to Cool Temperate Mixed Forest with fire-killed Mountain Ash, O’Shannassy Catchment, East Central Highlands (Arn Tolsma). © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2019 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo, the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning logo and the Arthur Rylah Institute logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Printed by Melbourne Polytechnic Printroom ISSN 1835-3827 (Print) ISSN 1835-3835 (pdf/online/MS word) ISBN 978-1-76077-589-6 (Print) ISBN 978-1-76077-590-2 (pdf/online/MS word) Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

Central Region

Section 3 Central Region 49 3.1 Central Region overview .................................................................................................... 51 3.2 Yarra system ....................................................................................................................... 53 3.3 Tarago system .................................................................................................................... 58 3.4 Maribyrnong system .......................................................................................................... 62 3.5 Werribee system ................................................................................................................. 66 3.6 Moorabool system .............................................................................................................. 72 3.7 Barwon system ................................................................................................................... 77 3.7.1 Upper Barwon River ............................................................................................... 77 3.7.2 Lower Barwon wetlands ........................................................................................ 77 50 3.1 Central Region overview 3.1 Central Region overview There are six systems that can receive environmental water in the Central Region: the Yarra and Tarago systems in the east and the Werribee, Maribyrnong, Moorabool and Barwon systems in the west. The landscape Community considerations The Yarra River flows west from the Yarra Ranges -

Aboriginal Heritage Impact Assessment Lancefield Road Precinct Structure Plan 1075 Sunbury, Victoria

Aboriginal Heritage Impact Assessment Lancefield Road Precinct Structure Plan 1075 Sunbury, Victoria Report Prepared for Metropolitan Planning Authority August 2015 Matt Chamberlain Executive Summary This report presents the results of an Aboriginal heritage impact assessment of a Precinct Structure Plan areas – PSP 1075 – situated at Sunbury, just north of Melbourne. The area is known as the Lancefield Road PSP (1075), covering an area of 1100 hectares on the east and north eastern side of Sunbury. The location of the study area is shown in Map 1. The purpose of the study is to provide findings and advice with regard to the Aboriginal heritage values of the PSP area. As part of this a range of tasks were outlined by Metropolitan Planning Authority, including: • Identifying the location of known Aboriginal sites (within 10 km radius of the PSP) and any natural features in the landscape that remain places of cultural importance today; • Collecting, documenting and reviewing oral histories and Aboriginal cultural values relating to the precinct; • Identifying Areas or landforms which are likely to be of high, medium and low cultural heritage sensitivity; • Identifying locations that are considered to be significantly disturbed as defined by the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006; • Undertaking an archaeological field survey with the Registered Aboriginal Party (RAP) (the Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Incorporated) to locate known and anticipated Aboriginal places within the precinct, with particular focus directed -

Maribyrnong River

Environmental Flow Determination for the Maribyrnong River Final Recommendations Revision C July 2006 Environmental Flow Determination for the Maribyrnong River –Final Recommendations Environmental Flow Determination for the Maribyrnong River FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS L:\work\NRG\PROJECTS\2005\034 Maribyrnong E-flows\02\03 Recommendations Paper\Recommendations RevC.doc Document History: ISSUE REVISION AUTHOR CHECKED APPROVED DESCRIPTION DATE NUMBER Preliminary Draft 30.11.2005 A A Wealands C Arnott C Arnott for Comment Final Draft for 18.01.2006 B A Wealands C Arnott C Arnott Comment Inclusion of 31.01.2006 B1 A Wealands C Arnott C Arnott estuary recommendations 18.07.2006 C A Wealands C Arnott C Arnott Final Report Natural Resources Group Earth Tech Engineering Pty Ltd ABN 61 089 482 888 Head Office 71 Queens Road Melbourne VIC 3004 Tel +61 3 8517 9200 Environmental Flow Determination for the Maribyrnong River –Final Recommendations Contents Contents .................................................................................................................. i Tables....................................................................................................................... i 1 Introduction ................................................................................................... 4 Outline of this Report.............................................................................................5 The Maribyrnong River Catchment .......................................................................6 2 Environmental -

Download Full Article 960.5KB .Pdf File

. https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1977.38.03 4 April 1977 GASTROPODS FROM SOME EARLY DEVONIAN LIMESTONES OF THE WALHALLA SYNCLINORIUM, CENTRAL VICTORIA By C. B. Tassell Albany Residency Museum, Port Road, Albany, W.A. Abstract Seventeen gastropods from Devonian limestones at Marble Creek (also known as Toon- gabbie), Deep Creek and Loyola within the Walhalla synclinorium are described. These include four new forms: Platyceras (Platyceras) mansfieldense and P. (Praenatica) sp. A. from Loyola, and P. {Platyceras) sp. A. and P. (Orthonychia) sp. A. from Marble Creek. The other described forms are all platyceratids except Tremanotus cyclocostatus and Michelia sp. from Marble Creek, Oriostoma sp. n., and an indeterminate turbiniform gastropod from Deep Creek and Scalaetrochus lindstromi from Loyola. Tropidodiscus centrifugalis and ITemnodiscus pharetroides from the mudstones at Loyola are also redescribed. The gastropod faunas of the limestones are dominated by coprophagic platyceratid gastropods and constitute further examples of this widely known crinoid-gastropod association. Introduction Gastropods from the Toongabbie Limestone, The limestone deposits along the eastern Marble Creek, were first noted by McCoy who limb of the Walhalla synclinorium each consist observed 'some traces of Gasteropoda, appar- of a number of small lenses of limestone. The ently of the genus Acroculia, too imperfect to determination possible, and a fragment deposits extend about 120 km from Loyola in render of Chap- the north, about 130 km north-east of Mel- Bellerophort Murray (1878, p. 49). Nisa (Veto- bourne, to Marble Creek in the south, about man (1907) noted the presence of brazieri Etheridge and Trochus (Scalae- 140 km east of Melbourne. -

Streamline Research Pty. Ltd. BB1 North – Orange Alignment BB1 (North) Presents the Most Southerly Crossing of Deep Creek

BB1 North – orange alignment BB1 (north) presents the most southerly crossing of Deep Creek and links in at the existing roundabout. Bulla Diggers Rest Road is proposed to be linked via a roundabout or T- intersection subject to grade considerations. BB1 South – light blue alignment BB1 (south) links into the existing Sunbury Road. This route traverses for 250 m along Deep Creek. Bulla Diggers Rest Road is proposed to be linked via a roundabout or T- intersection subject to grade considerations. BB2 – red alignment BB2 deviates from Somerton Road just before Wildwood Road towards the north. It then loops back southwards and in the process crosses Deep Creek before curving back towards the northern direction connecting into the OMR/Bulla Bypass interchange. BB3 - green alignment BB3 deviates northwards along Somerton Road, between Oaklands Road and Wildwood Road to avoid vegetation. It then loops back southwards where it bridges across Deep Creek. Similar to BB2, it connects into the OMR/Bulla Bypass interchange. Interim Bulla Bypass - Oaklands Road Duplication (light green alignment) VicRoads is investigating potential staging of this project. This may include duplicating Oaklands Road to a 4 lane divided road. This would connect Sunbury and Somerton Roads. 1.4 Waterways Deep Creek is the main waterway that could be affected by the proposed road works. Other waterways in near vicinity to the study area include Emu Creek, a tributary of Deep Creek to the north of Bulla and Jacksons Creek, a tributary to the south of Bulla. One additional waterway, Moonee Ponds Creek, is located to the east of the study area. -

A Rivers of the West Act

A Rivers of the West Act Draft proposals to protect and restore Melbourne’s western rivers and waterways and to defend the liveability of the West www.envirojustice.org.au Rivers of the West – Community workshop: Draft proposals 1 Executive Summary This report calls for the Victorian Parliament to enact legislation for the protection and restoration of rivers and waterways of Melbourne’s west. This Rivers of the West Act would be intended not only to establish a long-term framework to achieve healthy waterways but also to establish a new model of urban design that integrates natural places into community life, deepen accountability in decision- making and contribute to reconciliation with Indigenous communities. Legislative reform directed to protection of key environmental assets in the West concerns the liveability, well-being and public benefits available to communities in the West. In short, protection and restoration of the rivers and waterways of the west is a matter of environmental and social justice. The Act would adapt and build on measures now implemented in legislation for the Yarra River, such as legislated river protection principles, preparation of long-term landscape-scale strategic plans, and establishment of independent institutions to manage rivers and affected land. Expansion on the approach taken under the Yarra River Act would include formulation of landscape connectivity and guardianship principles for river management. The Act would require preparation of strategic plans for each key waterway in the West but also an overarching ‘biolinks’ framework to facilitate restoration across the landscapes of the West. Aboriginal ‘country planning’ would be integrated into this approach. -

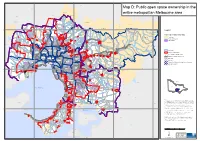

Map D: Public Open Space Ownership in Metropolitan Melbourne

2480000 2520000 2560000 2600000 ! JAMIESON ! FLOWERDALE ! ROMSEY ! WOODEND ! Map D: Public open space ownership in the Sunday Creek Reservoir Yarra State Forest entire metropolitan Melbourne area WALLAN ! Kinglake National Park MACEDON ! K E E R C LS L A F Y A R R A C R E E K Rosslynne Reservoir Toorourrong Reservoir Kinglake National Park K E E B R Yarra Ranges National Park C R K U EE G R C C R EW E A J I L ACKSO N V S K S G E C K E C N E R E O E R R R C L E Eildon State Forest E C Y I K BB E R U K R CR ME WHITTLESEA S ! MARYSVILLE ! K KINGLAKE Toolangi State Forest E ! Y D E A A 0 K D 0 R O W 0 E AR OA 0 R E C E N R 0 O K 0 E R L E N S Y D C E O R T C R T 0 R 0 F R N M U S B 4 E D 4 E A R Lerderderg State Park E A L A R B W M H - 4 P C Y N 4 U R S O 2 H 2 A V D WHITTLESEA I L B B L I K I L G IS E E - M W R Legend E Mount Ridley O T Yan Yean Reservoir I P C OD N-WO O V D S RTO Grasslands L U D RE Marysville State Forest PO B E E INT R S A E R K B O A R AD P R N E W O L E T IN B Y L I E T N R R C L FRENC K R I M O L H E E V EK A MA E Y N C R E C D E R R R E S E C K RY CREE R D K E SUNBURY E ! D K M AL A R Matlock State Forest COL O M O H C A C R N R Kinglake National Park D RA E K T B HUME E E S K E A S CRAIGIEBURN D E P R E ! PINNAC E K R Public open space ownership P I C L C E K N KORO E RE E G R S L E E R S A L K O ITKEN A N K E C C REE C E E I REE R T E K C W C T A Djerriwarrh Reservoir R K S G H E E S E N E D K O R O R W C T S N S E N N M S Cambarville State Forest O E K R T Crown land Craigieburn X L E A I B L Grasslands D E R -

Forest Management Plan for the Central Highlands 1998

FOREST MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE CENTRAL HIGHLANDS Department of Natural Resources and Environment May 1998 ii Copyright © Department of Natural Resources and Environment 1998 Published by the Department of Natural Resources and Environment PO Box 500, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia http://www.nre.vic.gov.au This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright owner. Victoria. Department of Natural Resources and Environment Forest management plan for the Central Highlands. Bibliography. 1. Forest management - Environmental aspects - Victoria - Central Highlands Region. 2. Forest conservation - Victoria - Central Highlands Region. 3. Forest ecology - Victoria - Central Highlands Region. 4. Biological diversity conservation - Victoria - Central Highlands Region. I. Title. 333.751609945 General Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaim all liability for any error, loss or other consequences which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Printed by Gill Miller Press Pty. Ltd. ISBN 0 7311 3159 2 (online version) iii FOREWORD Extending from Mt Disappointment in the west to Lake Eildon and the Thomson Reservoir, the forests of the Central Highlands of Victoria contain major environmental, cultural and economic resources. -

Excavations, Surveys and Heritage Management in Victoria

Excavations, Surveys and Heritage Management in Victoria Volume 3 2014 Excavations, Surveys and Heritage Management in Victoria Volume 3 2014 1 Excavations, Surveys and Heritage Management in Victoria Voume 3, 2014 Edited by Caroline Spry David Frankel Susan Lawrence Ilya Berelov Shaun Canning Front cover photograph Sisters Rocks. Courtesy Darren Griffin (photo taken on 17 October 2013) Excavations, Surveys and Heritage Management in Victoria Volume 3, 2014 Melbourne © 2014 The authors. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-9924332-3-9 2 Contents Editorial note 5 Papers Pleistocene to Holocene in the Upper Maribyrnong River Basin: excavations at Deep Creek, 7 Bulla William Anderson and Racheal Minos Investigation of a Pleistocene river terrace at Birrarrung Park, Lower Templestowe, Victoria 15 Martin Lawler, Ilya Berelov and Tim Cavanagh A Pleistocene date at Chelsea Heights, Victoria: evidence for Aboriginal occupation beneath 23 the Carrum Swamp Jim Wheeler, Alan N. Williams, Stacey Kennedy, Phillip S. Toms and Peter Mitchell Results of recent archaeological investigations along Wallpolla Creek, northwestern Victoria, 33 Australia Ben Watson and Paul Kucera The Browns Creek Community Archaeology Project: preliminary results from the survey and 43 excavation of a late Holocene shell midden on the Victorian coast Martin Lawler, Ron Arnold, Kasey F. Robb, Andy I.R. Herries, Tya Lovett, Christine Keogh, Matthew Phelan, Steven E. Falconer, Patricia L. Fall, Tiffany James-Lee and Ilya Berelov Hiding in plain sight: excavation of a lost pioneer homestead -

Maribyrnong STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS STATEMENT SEPTEMBER 2018

Maribyrnong STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS STATEMENT SEPTEMBER 2018 Integrated Water Management Forums Acknowledgement of Victoria’s Aboriginal communities The Victorian Government proudly acknowledges Victoria's Aboriginal communities and their rich culture and pays its respects to their Elders past and present. The government also recognises the intrinsic connection of Traditional Owners to Country and acknowledges their contribution to the management of land, water and resources. We acknowledge Aboriginal people as Australia’s fi rst peoples and as the Traditional Owners and custodians of the land and water on which we rely. We recognise and value the ongoing contribution of Aboriginal people and communities to Victorian life and how this enriches us. We embrace the spirit of reconciliation, working towards the equality of outcomes and ensuring an equal voice. © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Printed by Finsbury Green, Melbourne ISSN 2209-8216 – Print format ISSN 2209-8224 – Online (pdf/word) format Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without fl aw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication.