A Rivers of the West Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rivers Monitoring and Evaluation Plan V1.0 2020

i Rivers Monitoring and Evaluation Plan V1.0 2020 Contents Acknowledgement to Country ................................................................................................ 1 Contributors ........................................................................................................................... 1 Abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 Background and context ........................................................................................................ 3 About the Rivers MEP ............................................................................................................. 7 Part A: PERFORMANCE OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................... 18 Habitat ................................................................................................................................. 24 Vegetation ............................................................................................................................ 29 Engaged communities .......................................................................................................... 45 Community places ................................................................................................................ 54 Water for the environment .................................................................................................. -

Post-Fire Dynamics of Cool Temperate Rainforest in the O'shannassy Catchment

Post-fire dynamics of Cool Temperate Rainforest in the O’Shannassy Catchment A. Tolsma, R. Hale, G. Sutter and M. Kohout July 2019 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 298 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning PO Box 137 Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Phone (03) 9450 8600 Website: www.ari.vic.gov.au Citation: Tolsma, A., Hale, R., Sutter, G. and Kohout, M. (2019). Post-fire dynamics of Cool Temperate Rainforest in the O’Shannassy Catchment. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 298. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Heidelberg, Victoria. Front cover photo: Small stand of Cool Temperate Rainforest grading to Cool Temperate Mixed Forest with fire-killed Mountain Ash, O’Shannassy Catchment, East Central Highlands (Arn Tolsma). © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2019 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo, the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning logo and the Arthur Rylah Institute logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Printed by Melbourne Polytechnic Printroom ISSN 1835-3827 (Print) ISSN 1835-3835 (pdf/online/MS word) ISBN 978-1-76077-589-6 (Print) ISBN 978-1-76077-590-2 (pdf/online/MS word) Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

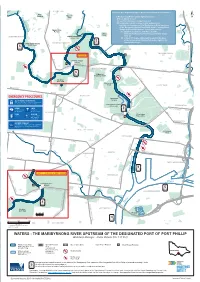

THE MARIBYRNONG RIVER UPSTREAM of the DESIGNATED PORT of PORT PHILLIP Waterway Manager - Parks Victoria (Ph: 131 963)

KEILOR EAST Exclusive Use & Special Purpose Areas for the Purpose of Clause 13. Allan Reserve Rosehill Maribyrnong ROAD Park a) Maribyrnong River- special light provisions N Creek A Recreational Vessel- (i) used for training or competition;ESSENDON and (ii) is not powered but is propelled by using oars or paddles; on the waters of the Maribyrnong River upstream of the Designated Port of Port Phillip to the Canning Street Moonee Monte Carlo Bridge shall exhibit between sunset and sunrise - Reserve (i) a light in accordance with Rule 25 of the MILLEARA Steele Clifton International Rules for Preventing Collisions at Sea, Park SUNSHINE NORTH LOWER MARIBYRNONG 1972; or RIVER LAND (ii) a fixed 180 degree white light located on the bow MILITARY of the vessel and a flashing 180 degree light on the Ponds AVONDALE HEIGHTS stern of the vessel. LOWER MARIBYRNONG RIVER LAND ABERFELDIE MOONEE PONDS CITYLINK See Inset A ROAD CANNING STREET BRIDGE CORDITE ROAD Creek RALEIGH AVENUE MARIBYRNONG STREET MARIBYRNONG ROAD ORMOND ROAD CANNING River Highpoint River Shopping Centre EPSOM Medway Golf Club ROAD Pipemakers Park ASCOT VALE BALLARAT ROAD HAMPSTEAD MAIDSTONE LANGS ROAD Thompson Reserve STREET BALLARAT LOWER MARIBYRNONG RIVER LAND FLEMINGTON AVENUE RACECOURSE ROAD ROAD BRAYBROOK ROAD Flemington FARNSWORTH Racecourse Creek SMITHFIELD KENSINGTON ROAD MACAULAY ROAD ASHLEY WEST FOOTSCRAY J J Holland Park SUNSHINE ROAD Stony FOOTSCRAY DYNON ROAD ROAD STREET DEMPSTER GEELONG TOTTENHAM ROAD Creek STREET SEDDON FOOTSCRAY Ponds KINGSVILLE CITYLINK ROAD ROAD -

Rivers and Streams Special Investigation Final Recommendations

LAND CONSERVATION COUNCIL RIVERS AND STREAMS SPECIAL INVESTIGATION FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS June 1991 This text is a facsimile of the former Land Conservation Council’s Rivers and Streams Special Investigation Final Recommendations. It has been edited to incorporate Government decisions on the recommendations made by Order in Council dated 7 July 1992, and subsequent formal amendments. Added text is shown underlined; deleted text is shown struck through. Annotations [in brackets] explain the origins of the changes. MEMBERS OF THE LAND CONSERVATION COUNCIL D.H.F. Scott, B.A. (Chairman) R.W. Campbell, B.Vet.Sc., M.B.A.; Director - Natural Resource Systems, Department of Conservation and Environment (Deputy Chairman) D.M. Calder, M.Sc., Ph.D., M.I.Biol. W.A. Chamley, B.Sc., D.Phil.; Director - Fisheries Management, Department of Conservation and Environment S.M. Ferguson, M.B.E. M.D.A. Gregson, E.D., M.A.F., Aus.I.M.M.; General Manager - Minerals, Department of Manufacturing and Industry Development A.E.K. Hingston, B.Behav.Sc., M.Env.Stud., Cert.Hort. P. Jerome, B.A., Dip.T.R.P., M.A.; Director - Regional Planning, Department of Planning and Housing M.N. Kinsella, B.Ag.Sc., M.Sci., F.A.I.A.S.; Manager - Quarantine and Inspection Services, Department of Agriculture K.J. Langford, B.Eng.(Ag)., Ph.D , General Manager - Rural Water Commission R.D. Malcolmson, M.B.E., B.Sc., F.A.I.M., M.I.P.M.A., M.Inst.P., M.A.I.P. D.S. Saunders, B.Agr.Sc., M.A.I.A.S.; Director - National Parks and Public Land, Department of Conservation and Environment K.J. -

The Wolfram Mine at Wilks Creek, Victoria by PETER S

Journal of Australasian Mining History, Vol. 13, October 2015 The Wolfram Mine at Wilks Creek, Victoria By PETER S. EVANS ungsten, a hard, steel-grey metal is an important strategic commodity. Historic uses included textile printing and the production of hard alloys for engineering T purposes. In the twentieth century it was an essential element in the heavy manufacturing and armaments industry, and was also used in incandescent lamps, radio valves, electric furnaces, and spark plugs. Steels alloyed with tungsten are especially hard and fine-grained and retain their working properties at high temperatures. The principle ores of tungsten are scheelite and wolframite. Scheelite (calcium tungstate, CaWO4) is a tetragonal crystalline ore named after its discoverer Carl Wilhelm Scheele, a Swedish chemist. Wolframite (a mixture of ferrous tungstate, FeWO4; and manganese tungstate, MnWO4) has a monoclinic crystal structure and takes its name from the early word for tungsten, wolfram.1 Both of these minerals occur worldwide but more than 75 per cent of current world production comes from China.2 The existence of tungsten ores in Victoria was well known by 1869. Wolframite was noted in association with gold reefs at Sandhurst (Bendigo), Smythesdale, Tarrengower and in the basin of the River Yarra.3 Contemporary values for the mineral in England were from £5 to £6 per ton ‘at grass’. A method of refining the ore was known but, with the mining industry in Victoria largely focussed on gold production, little was done to exploit this resource.4 Towards the end of the nineteenth century, industrialised European nations showed an interest in buying Australian ores of tungsten, with well-dressed scheelite fetching £30 or more per ton on the European market. -

Maribyrnong STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS STATEMENT SEPTEMBER 2018

Maribyrnong STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS STATEMENT SEPTEMBER 2018 Integrated Water Management Forums Acknowledgement of Victoria’s Aboriginal communities The Victorian Government proudly acknowledges Victoria's Aboriginal communities and their rich culture and pays its respects to their Elders past and present. The government also recognises the intrinsic connection of Traditional Owners to Country and acknowledges their contribution to the management of land, water and resources. We acknowledge Aboriginal people as Australia’s fi rst peoples and as the Traditional Owners and custodians of the land and water on which we rely. We recognise and value the ongoing contribution of Aboriginal people and communities to Victorian life and how this enriches us. We embrace the spirit of reconciliation, working towards the equality of outcomes and ensuring an equal voice. © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Printed by Finsbury Green, Melbourne ISSN 2209-8216 – Print format ISSN 2209-8224 – Online (pdf/word) format Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without fl aw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

Central Region

Section 3 Central Region 49 3.1 Central Region overview .................................................................................................... 51 3.2 Yarra system ....................................................................................................................... 53 3.3 Tarago system .................................................................................................................... 58 3.4 Maribyrnong system .......................................................................................................... 62 3.5 Werribee system ................................................................................................................. 66 3.6 Moorabool system .............................................................................................................. 72 3.7 Barwon system ................................................................................................................... 77 3.7.1 Upper Barwon River ............................................................................................... 77 3.7.2 Lower Barwon wetlands ........................................................................................ 77 50 3.1 Central Region overview 3.1 Central Region overview There are six systems that can receive environmental water in the Central Region: the Yarra and Tarago systems in the east and the Werribee, Maribyrnong, Moorabool and Barwon systems in the west. The landscape Community considerations The Yarra River flows west from the Yarra Ranges -

Aboriginal Heritage Impact Assessment Lancefield Road Precinct Structure Plan 1075 Sunbury, Victoria

Aboriginal Heritage Impact Assessment Lancefield Road Precinct Structure Plan 1075 Sunbury, Victoria Report Prepared for Metropolitan Planning Authority August 2015 Matt Chamberlain Executive Summary This report presents the results of an Aboriginal heritage impact assessment of a Precinct Structure Plan areas – PSP 1075 – situated at Sunbury, just north of Melbourne. The area is known as the Lancefield Road PSP (1075), covering an area of 1100 hectares on the east and north eastern side of Sunbury. The location of the study area is shown in Map 1. The purpose of the study is to provide findings and advice with regard to the Aboriginal heritage values of the PSP area. As part of this a range of tasks were outlined by Metropolitan Planning Authority, including: • Identifying the location of known Aboriginal sites (within 10 km radius of the PSP) and any natural features in the landscape that remain places of cultural importance today; • Collecting, documenting and reviewing oral histories and Aboriginal cultural values relating to the precinct; • Identifying Areas or landforms which are likely to be of high, medium and low cultural heritage sensitivity; • Identifying locations that are considered to be significantly disturbed as defined by the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006; • Undertaking an archaeological field survey with the Registered Aboriginal Party (RAP) (the Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Incorporated) to locate known and anticipated Aboriginal places within the precinct, with particular focus directed -

Flood Management and Drainage Strategy

Port Phillip and Westernport Region Flood Management and Drainage Strategy i “Ideallysocietywouldliketobefreeoftheriskofflooding, butthisisneitherpracticallynoreconomicallyfeasible. Whatconstitutesanacceptableleveloffloodriskhowever isavexedquestion.Theimmediateriskisbornebythe community,whichmusthaveasignificantinputintodefining theacceptablelevel.Tothisend,publicconsultationandrisk communicationisveryimportant.” Floodplain Management In Australia Best Practice Principles and Guidelines, (SCARM 2000) Development of this strategy has been guided by a steering committee headed by an independent chair, Rob Joy, with representatives from the following organisations: • Department of Sustainability and Environment • Office of the Emergency Services Commissioner • Shire of Macedon Ranges • Insurance industry • Department of Human Services • Municipal Association of Victoria • Stormwater Industry Association of Victoria • Institute of Public Works Engineers Victoria • Port Phillip and Westernport Catchment Management Authority • Melbourne Water. The strategy has been prepared following extensive consultation with flood management agencies and local government authorities in the Port Phillip and Westernport region. Stakeholder workshops were undertaken to identify issues of concern and submissions received in relation to a circulated discussion paper assisted in the formulation of future strategic actions. iii LollipopCreek,Werribee,February2005 iv FloodManagementandDrainageStrategy Contents 2 Introduction 6 Background 6 What is flooding? 8 Types -

5. South East Coast (Victoria)

5. South East Coast (Victoria) 5.1 Introduction ................................................... 2 5.5 Rivers, wetlands and groundwater ............... 19 5.2 Key data and information ............................... 3 5.6 Water for cities and towns............................ 28 5.3 Description of region ...................................... 5 5.7 Water for agriculture .................................... 37 5.4 Recent patterns in landscape water flows ...... 9 5. South East Coast (Vic) 5.1 Introduction This chapter examines water resources in the Surface water quality, which is important in any water South East Coast (Victoria) region in 2009–10 and resources assessment, is not addressed. At the time over recent decades. Seasonal variability and trends in of writing, suitable quality controlled and assured modelled water flows, stores and levels are considered surface water quality data from the Australian Water at the regional level and also in more detail at sites for Resources Information System (Bureau of Meteorology selected rivers, wetlands and aquifers. Information on 2011a) were not available. Groundwater and water water use is also provided for selected urban centres use are only partially addressed for the same reason. and irrigation areas. The chapter begins with an In future reports, these aspects will be dealt with overview of key data and information on water flows, more thoroughly as suitable data become stores and use in the region in recent times followed operationally available. by a brief description of the region. -

Maribyrnong River

Environmental Flow Determination for the Maribyrnong River Final Recommendations Revision C July 2006 Environmental Flow Determination for the Maribyrnong River –Final Recommendations Environmental Flow Determination for the Maribyrnong River FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS L:\work\NRG\PROJECTS\2005\034 Maribyrnong E-flows\02\03 Recommendations Paper\Recommendations RevC.doc Document History: ISSUE REVISION AUTHOR CHECKED APPROVED DESCRIPTION DATE NUMBER Preliminary Draft 30.11.2005 A A Wealands C Arnott C Arnott for Comment Final Draft for 18.01.2006 B A Wealands C Arnott C Arnott Comment Inclusion of 31.01.2006 B1 A Wealands C Arnott C Arnott estuary recommendations 18.07.2006 C A Wealands C Arnott C Arnott Final Report Natural Resources Group Earth Tech Engineering Pty Ltd ABN 61 089 482 888 Head Office 71 Queens Road Melbourne VIC 3004 Tel +61 3 8517 9200 Environmental Flow Determination for the Maribyrnong River –Final Recommendations Contents Contents .................................................................................................................. i Tables....................................................................................................................... i 1 Introduction ................................................................................................... 4 Outline of this Report.............................................................................................5 The Maribyrnong River Catchment .......................................................................6 2 Environmental -

Victoria Government Gazette No

Victoria Government Gazette No. S 89 Tuesday 22 June 1999 By Authority. Victorian Government Printer SPECIAL Environment Protection Act 1970 VARIATION OF THE STATE ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION POLICY (WATERS OF VICTORIA) - INSERTION OF SCHEDULE F7. WATERS OF THE YARRA CATCHMENT The Governor in Council under section 16(2) of the Environment Protection Act 1970 and on the recommendation of the Environment Protection Authority declares as follows: Dated 22 June 1999. Responsible Minister: MARIE TEHAN Minister for Conservation and Land Management SHANNON DELLAMARTA Acting Clerk of the Executive Council 1. Contents This Order is divided into parts as follows - PART 1 - PRELIMINARY 2. Purposes 3. Commencement 4. The Principal Policy PART 2 - VARIATION OF THE PRINCIPAL POLICY 5. Insertion of new Schedule F7. Waters of the Yarra Catchment PART 3 - REVOCATION OF REDUNDANT STATE ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION POLICY 6. Revocation of State environment protection policy NO. W-29 (Waters of the Yarra River and Tributaries) PART 1 - PRELIMINARY 2. Purposes The purposes of this Order are to - (a) vary the State environment protection policy (Waters of Victoria) to add to Schedule F a new schedule - Schedule F7. Waters of the Yarra Catchment; and (b) revoke the State environment protection policy NO. W-29 (Waters of the Yarra River and Tributaries) 3. Commencement This Order comes into effect upon publication in the Government Gazette. 4. The Principal Policy In this Order, the State environment protection policy (Waters of Victoria) is called the ÒPrincipal PolicyÓ. PART 2 - VARIATION OF THE PRINCIPAL POLICY 5. Insertion of new Schedule F7. Waters of the Yarra Catchment After Schedule F6.