Evolving As Skipper Or Crew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) Version 20 APR 2016

The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) Version 20 APR 2016 Welcome to the Junk Rig Glossary! The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) is a Member Project of the Junk Rig Association, initiated by Bruce Weller who, as a then new member, found that he needed a junk 'dictionary’. The aim is to create a comprehensive and fully inclusive glossary of all terms pertaining to junk rig, its implementation and characteristics. It is intended to benefit all who are interested in junk rig, its history and on-going development. A goal of the JRG Project is to encourage a standard vocabulary to assist clarity of expression and understanding. Thus, where competing terms are in common use, one has generally been selected as standard (please see Glossary Conventions: Standard Versus Non-Standard Terms, below) This is in no way intended to impugn non-standard terms or those who favour them. Standard usage is voluntary, and such designations are wide open to review and change. Where possible, terminology established by Hasler and McLeod in Practical Junk Rig has been preferred. Where innovators have developed a planform and associated rigging, their terminology for innovative features is preferred. Otherwise, standards are educed, insofar as possible, from common usage in other publications and online discussion. Your participation in JRG content is warmly welcomed. Comments, suggestions and/or corrections may be submitted to [email protected], or via related fora. Thank you for using this resource! The Editors: Dave Zeiger Bruce Weller Lesley Verbrugge Shemaya Laurel Contents Some sections are not yet completed. ∙ Common Terms ∙ Common Junk Rigs ∙ Handy references Common Acronyms Formulae and Ratios Fabric materials Rope materials ∙ ∙ Glossary Conventions Participation and Feedback Standard vs. -

March 30, 2017 Mr. Herb Pollard, Chair Pacific Fishery Management

Agenda Item B.1.b Supplemental Public Comment 3 Full Version Electronic Only April 2017 March 30, 2017 Mr. Herb Pollard, Chair Pacific Fishery Management Council 7700 NE Ambassador Place, Suite 101 Portland, OR 97220-1384 Mr. Barry Thom West Coast Regional Administrator National Marine Fisheries Service West Coast Region 7600 Sand Point Way NE, Bldg. 1 Seattle, WA 98115-0070 RE: Agenda Item B.1: Open Comment Period – Opposition to Pelagic Longlines off the U.S. West Coast Dear Mr. Pollard, Mr. Thom, and Council Members: You have the shared privilege and responsibility to protect the ocean’s most majestic wildlife. That responsibility includes ensuring ocean wildlife can safely swim Pacific Ocean waters without being killed in commercial fishing gear. We, the undersigned 24,494 residents of the United States (including 6,106 residents of California, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington), urge you to prevent the authorization of pelagic longline fishing gear off the U.S. Pacific Coast. Use of this gear would lead to the entanglement and death of sea turtles, dolphins, whales, sea birds, sharks and many other important ocean species. Pelagic longlines used to catch swordfish, which can reach 60 miles in length and trail thousands of baited hooks, will inevitably ensnare and drown many other unsuspecting marine animals. Such a U.S. West Coast-based pelagic longline fishery, whether deep-set or shallow-set, has no place among the diversity of ocean life of the Northeast Pacific, particularly species already endangered with extinction. Pacific leatherback sea turtles, for example, migrate 6,000 miles from their nesting beaches to feed in the productive waters off the U.S. -

Member Orientation Package Revised 2015

SUS Member Orientation Package Revised 2015 We welcome you to Singles Under Sail, Inc. SUS members are required to meet certain education requirements. It is mandatory for all NEW members to have met the following requirements by their second membership renewal date: 1) To have completed the SUS Dockside Orientation Class (DOC), AND 2) To have passed either the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary's or the U.S. Power Squadron's Basic Boating Course (8 hours minimum), OR provide proof of having held a U.S. Coast Guard Captain’s license, AND 3) To attend an SUS Member Orientation Class (MOC). See the SUS Bylaws (attached) for additional information. In the Member Orientation Class (which lasts approximately 1-1/2 hours) we will review SUS policies, procedures and guidelines and give you an opportunity to ask questions about the Club. The Dockside Orientation Class is approximately 4 hours and given on a docked boat (usually one of the SUS Skipper’s boats). We encourage everyone to enhance SUS sailing activities with sailing and boating classes. We believe it is important for all members to become active, contributing, participants in SUS. In return you can enjoy great sailing, programs and social events with some of the best people you may ever meet. This booklet contains all the information you will need to become an active participant in SUS. BRING THIS BOOK WITH YOU TO THE MOC. http://www.singlesundersail.org VISIT THE SUS WEBSITE singlesundersail.org for additional information and updates. The site requires a user name and password to access members only material. -

Cruising History

Portland Yacht Club A History of Cruising Activity The Portland Yacht Club traces its routes to a weekend cruise to Boothbay Harbor by several Portlanders in the mid 1860's. This venture was the impetus that began a discussion about forming a yacht club. This was followed by a meeting in June 1868, at which time they decided if they could sign 100 members they would move forward. On April 26, 1869 their initiative was rewarded with the creation of the Portland Yacht Club. During the first year, the club held another cruise to Boothbay Harbor. Departing Boothbay, they went up the Sasanoa (hopefully with the tide) to Bath. The next day they sailed down the Kennebec River (again hopefully with a fair tide) to Jewel Island where “a Grand Clam Bake” was held. The entire three day cruise was enshrouded in fog and supposedly continued for the next 34 years (some things never change). But, think of the seamanship and navigation skills required to ply those waters in a vessel with no power other than the wind while using less than reliable charts, compass, watch and taffrail log. Present day cruisers are now quite spoiled with the electronics available. In 1873 the club held both a spring and fall cruise along with 30 boats participating in Portland's July 4th Celebration. The spring cruise of 1879 included 4 schooners and 2 sloops. They departed the club at 1000 and arrived in Wiscasset at 1620. The sloop Vif went aground on Merrill's Ledge in the Sheepscot. As the saying goes, “There are two types of sailors in Maine, those that have been aground and those that will go aground”. -

Jackline Update

A P R I L 2 0 2 1 JACKLINE INSURANCE PROGRAM 2021 NEWS & UPDATES FEAR NO HORIZON - INSURANCE FOR GLOBAL CRUISERS & LIVING ABOARD The Jackline Insurance Program by Gowrie Group is a comprehensive insurance program designed to protect yachts and their owners cruising throughout the world. Our marine insurance experts understand the cruising lifestyle, and work with our clients to create customized insurance solutions to align with cruising plans and coverage needs. The Jackline Program includes key protection important to cruisers, such as world-wide navigation, approval for living aboard with a crew of two, personal property coverage, mechanical breakdown, ice damage, pollution liability, reef damage liability, loss of use, and more. The program is endorsed by Seven Seas Cruising Association (SSCA), underwritten by Markel Insurance, and managed by Gowrie Group, a Division of Risk Strategies. CONTENTS INSURANCE MARKET - UPDATE FOR CRUISERS The insurance marketplace has experienced unprecedented forces and undergone significant changes in the past few years. 2020 presented not only a global pandemic, but also delivered a Fear No Horizon continuation of the multi-year trend of extremely active, destructive, and costly Atlantic Hurricane Seasons. Many insurance companies have reacted to the multi-year catastrophic losses, by reevaluating their rates and in some cases, exiting the marine insurance market. These changes Insurance Market Update have left thousands of boat owners with a policy scheduled for non-renewal, and limited options for how to secure new coverage. Did You Know? The Jackline Insurance Program, underwritten by Markel and managed by Gowrie Group, is proud to confirm that we are committed to our cruising clients, and we have no plans to exit from the marine insurance market. -

Hornblower's Ships

Names of Ships from the Hornblower Books. Introduction Hornblower’s biographer, C S Forester, wrote eleven books covering the most active and dramatic episodes of the life of his subject. In addition, he also wrote a Hornblower “Companion” and the so called three “lost” short stories. There were some years and activities in Hornblower’s life that were not written about before the biographer’s death and therefore not recorded. However, the books and stories that were published describe not only what Hornblower did and thought about his life and career but also mentioned in varying levels of detail the people and the ships that he encountered. Hornblower of course served on many ships but also fought with and against them, captured them, sank them or protected them besides just being aware of them. Of all the ships mentioned, a handful of them would have been highly significant for him. The Indefatigable was the ship on which Midshipman and then Acting Lieutenant Hornblower mostly learnt and developed his skills as a seaman and as a fighting man. This learning continued with his experiences on the Renown as a lieutenant. His first commands, apart from prizes taken, were on the Hotspur and the Atropos. Later as a full captain, he took the Lydia round the Horn to the Pacific coast of South America and his first and only captaincy of a ship of the line was on the Sutherland. He first flew his own flag on the Nonsuch and sailed to the Baltic on her. In later years his ships were smaller as befitted the nature of the tasks that fell to him. -

Meet the Competitors: Annapolis YC Double-Handed Distance Race

Meet the Competitors: Annapolis YC Double-handed Distance Race R.J. Cooper & Courtney Cooper Cumberland are a brother and sister team from Oxford, Maryland and Panama City, Florida. They have sailed together throughout their youth as well as while on the Sailing Team for the University of Florida. The pair has teamed up for a bid to represent the United States and win gold at the 2024 Olympics in Paris. They will be sailing Tenacious owned by AYC member Carl Gitchell. Sail #501 Erik Haaland and Andrew Waters will be sailing the new Italia Yachts 9.98 sport boat named Vichingio (Viking). Erik Haaland is the Sales Director for Italia Yachts USA at David Walters Yachts. He has sailed his entire life and currently races on performance sport boats including the Farr 30, Melges 32 and J70. Andrew Waters is a Sail and Service Consultant at Quantum Sails in Annapolis. His professional sailing career began in South Africa and later the Caribbean and includes numerous wins in large regattas. Sail #17261 Ethan Johnson and Cat Chimney have sailing experience in dinghies, foiling skiffs, offshore racers and mini-Maxis. Ethan, a Southern Maryland native now living in NY is excited to be racing in home waters. Cat was born on Long Island, NY but spent time in Auckland, New Zealand. She has sailed with Olympians, America’s Cup sailors and Volvo Ocean Race sailors. Cat is Technical Specialist and Rigger at the prestigious Oakcliff Sailing where Ethan also works as the Training Program Director. Earlier this year Cat and Ethan teamed up to win the Oakcliff Double-handed Melges 24 Distance Race. -

How the Beaufort Scale Affects Your Sail Plan

How the Beaufort scale affects your sail plan The Beaufort scale is a measurement that relates wind speed to observed conditions at sea. Used in the sea area forecast it allows sailors to anticipate the condition that they are likely to face. Modern cruising yachts have become wider over the years to allow more room inside the boat when berthed. This offers the occupants a large living space but does have an effect on the handling of the boat. A wide beam, relatively short keel and rudder mean that if they have too much sail up they have a greater tendency to broach into the wind. Broaching, although dramatic for those onboard, is nothing more than the boat turning into the wind and is easy to rectify by carrying less sail. If the helm is struggling to keep the boat in a straight line then the boat has too much ‘weather helm’ i.e. the boat keeps turning into the wind- in this instance it is necessary to reduce sail. Racer/cruisers are often narrower than their cruising counter parts, with longer keels and rudders which mean they are less likely to broach, but often more difficult to sail with a small crew. Cruising yachts often have large overlapping jibs or genoas and relevantly small main sails. This allows the sail area to be reduced quickly and easily simply by furling away some head sail. The main sail is used to balance boat as the main drive comes from the head sail. Racer cruisers will often have smaller jibs and larger main sails, so reducing the sail area means reefing the main sail first and using the jib to balance the boat. -

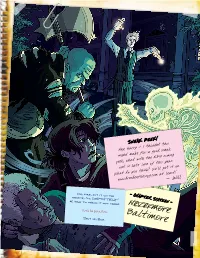

N O P Q R S T U V W X

n o p q r s t u SNEAK PEEK! hey, harry — i thought this v might make for a good sneak peek, what with the RPG coming out in late June of this year. What do you think? We’ll put it on w www.dresdenfilesrpg.com at least! — Will Oh, sure, put it on the website, I’ll DEFINITELY x be able to check it out there. - Chapter Sixteen - - Don’t be pissy, Boss. n-evermore y Shut up, Bob. Baltimore z a nevermore/Baltimore sector. Financial services, education, tourism, Who Am I? and health services are dominating. Johns Hi. I’m Davian Campbell, a grad student b Hopkins is currently the biggest employer (not at the University of Chicago and one of the to mention a huge landowner), where it used translation: Alphas. Billy asked me to write up some- i helped to be Bethlehem Steel. Unemployment is high. thing about Baltimore for this game he’s Lots of folks are unhappy. Davian move writing. I guess he figured since I grew up Climate: They don’t get much snow in last august. there, I’d know it. I tried to tell him that c I haven’t lived there for years, and that Baltimore—two, maybe three times a year we 50 boxes of get a couple of inches. When that happens, books = a between patrolling, trying to finish my thesis, and our weekly game session, I don’t the entire town goes freaking loco. Stay off the favor or two. have time for this stuff. -

Britannia Yacht Club New Member's Guide Your Cottage in the City!

Britannia Yacht Club New Member’s Guide Your Cottage in the City! Britannia Yacht Club 2777 Cassels St. Ottawa, Ontario K2B 6N6 613 828-5167 [email protected] www.byc.ca www.facebook.com/BYCOttawa @BYCTweet Britannia_Yacht_Club Welcome New BYC Member! Your new membership at the Britannia Yacht Club is highly valued and your fellow members, staff and Board of Directors want you to feel very welcome and comfortable as quickly as possible. As with all new things, it does take time to find your way around. Hopefully, this New Member’s Guide answers the most frequently asked questions about the Club, its services, regulations, procedures, etiquette, etc. If there is something that is not covered in this guide, please do not hesitate to direct any questions to the General Manager, Paul Moore, or our office staff, myself or other members of the Board of Directors (see contacts in the guide), or, perhaps more expediently on matters of general information, just ask a fellow member. It is important that you thoroughly enjoy being a member of Britannia Yacht Club, so that no matter the main reason for you joining – whether it be sailing, boating, tennis or social activity – the club will be “your cottage in the city” where you can spend many long days of enjoyment, recreation and relaxation. See you at the club. Sincerely, Rob Braden Commodore Britannia Yacht Club [email protected] Krista Kiiffner Director of Membership Britannia Yacht Club [email protected] Britannia Yacht Club New Member’s Guide Table of Contents 1. ABOUT BRITANNIA YACHT CLUB ..................................................... -

Journal of the of Association Yachting Historians

Journal of the Association of Yachting Historians www.yachtinghistorians.org 2019-2020 The Jeremy Lines Access to research sources At our last AGM, one of our members asked Half-Model Collection how can our Association help members find sources of yachting history publications, archives and records? Such assistance should be a key service to our members and therefore we are instigating access through a special link on the AYH website. Many of us will have started research in yacht club records and club libraries, which are often haphazard and incomplete. We have now started the process of listing significant yachting research resources with their locations, distinctive features, and comments on how accessible they are, and we invite our members to tell us about their Half-model of Peggy Bawn, G.L. Watson’s 1894 “fast cruiser”. experiences of using these resources. Some of the Model built by David Spy of Tayinloan, Argyllshire sources described, of course, are historic and often not actively acquiring new material, but the Bartlett Over many years our friend and AYH Committee Library (Falmouth) and the Classic Boat Museum Member the late Jeremy Lines assiduously recorded (Cowes) are frequently adding to their specific yachting history collections. half-models of yachts and collected these in a database. Such models, often seen screwed to yacht clubhouse This list makes no claim to be comprehensive, and we have taken a decision not to include major walls, may be only quaint decoration to present-day national libraries, such as British, Scottish, Welsh, members of our Association, but these carefully crafted Trinity College (Dublin), Bodleian (Oxford), models are primary historical artefacts. -

Daily Eastern News: March 25, 2003 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep March 2003 3-25-2003 Daily Eastern News: March 25, 2003 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: March 25, 2003" (2003). March. 11. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2003 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in March by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Thll the troth March 25, 2003 + T UE S D A V and don't be afraid. • VO LUME 87 . NUMBER 120 THE DA ILYEASTERN NEWS . COM Winning one for THE DAILY the Gipper Panthers try to give head coach Jim Schmitz his 400th win at Saint Louis. EASTERN NEWS Page 12 Current conflict not technically a 'war ' for U.S. By Avian Carrasquilo STUDENT GOVERNMENT ED ITOR Stornns,resistCUlce For almost a week now news broadcasts have been dominated slow movement into by coverage with the banners and slick graphics proclaiming Iraqi capital city "War in Iraq. • But debate exists whether the By The Associated Press United States is currently in a war because President George W. U.S.-led warplanes and heli Bush has never gotten Congress' copters attacked Republican approval for such action. Guard units defending Scott Stanzel, of the White Baghdad on Monday while House Press Secretary's office, ground troops advanced to said Congress has supported the within 50 miles of the Iraqi use of force in Iraq and that capital.