In New Iranian Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andrej Sakharov 19 Elena Bonner, Compagna Di Vita 21

a cura di Stefania Fenati Francesca Mezzadri Daniela Asquini Presentazione di Stefania Fenati 5 Noi come gli altri, gli altri come noi di Simonetta Saliera 9 L’Europa è per i Diritti Umani di Bruno Marasà 13 Il Premio Sakharov 15 Andrej Sakharov 19 Elena Bonner, compagna di vita 21 Premio Sakharov 2016 25 Nadia Murad Basee Taha e Lamiya Aji Bashar, le ragazze yazide Premio Sakharov 2015 35 Raif Badawi, il blogger che ha criticato l’Arabia Saudita Premio Sakharov 2014 43 Denis Mukwege, il medico congolese che aiuta le donne Premio Sakharov 2013 53 Malala Yousafzai, la ragazza pakistana Premio Sakharov 2012 59 Jafar Panahi, il regista indiano Nasrin Sotoudeh, l’avvocatessa iraniana Premio Sakharov 2011 69 Mohamed Bouazizi - Asmaa Mahfouz - Ali Ferzat - Razan Zaitouneh - Ahmed Al-Sanusi - Le donne e la Primavera araba Glossario 89 Carta dei Diritti Fondamentali dell’Unione Europea 125 Presentazione Stefania Fenati Responsabile Europe Direct Emilia-Romagna Il Premio Sakharov rappresenta un importante momento nel quale ogni anno, dal 1988 ad oggi, la voce dell’Unione europea si fa senti- re contro qualsiasi violazione dei diritti umani nel mondo, e riafferma la necessità di lavorare costantemente per il progresso dell’umanità. Ogni anno il Parlamento europeo consegna al vincitore del Premio Sakharov una somma di 50.000 euro nel corso di una seduta plena- ria solenne che ha luogo a Strasburgo verso la fine dell’anno. Tutti i gruppi politici del Parlamento possono nominare candidati, dopodi- ché i membri della commissione per gli affari esteri, della commis- sione per lo sviluppo e della sottocommissione per i diritti dell’uomo votano un elenco ristretto formato da tre candidati. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Bollywood's Periphery: Child Stars and Representations of Childhood in Hindi Films

Shakuntala Banaji Bollywood's periphery: child stars and representations of childhood in Hindi films Book section Original citation: Originally published in Bollywood's periphery: child stars and representations of childhood in Hindi films. In: O'Connor, Jane and Mercer, John, (eds.) Childhood and Celebrity. Routledge, London, UK. ISBN 9781138855274 © 2016 The Author This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/65482/ Available in LSE Research Online: February 2017 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Title: Bollywood's periphery: child stars and representations of childhood in Hindi films Author: Shakuntala Banaji, Introduction The three research questions which I explore in this chapter ask: How do international accounts of children’s role on screen and child performance -

Download File (Pdf; 3Mb)

Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS ISSUEISSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CINEMACINEMA ● IIndianndian camera,camera, IranianIranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd dramaticdramatic rootsroots ofof thethe IranianIranian NewNew WaveWave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran inin ‘Film‘Film Farsi’Farsi’ popularpopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: socio-politicalsocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed asas villagevillage foolfool ● TThehe nnoiroir worldworld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ofof IranianIranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred Defence’Defence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar Farhadi’sFarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew diasporicdiasporic visionsvisions ofof IranIran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews andand eventsevents inin LondonLondon Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS IISSUESSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CCINEMAINEMA ● IIndianndian ccamera,amera, IIranianranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd ddramaticramatic rootsroots ooff thethe IIranianranian NNewew WWaveave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran iinn ‘Film-Farsi’‘Film-Farsi’ ppopularopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: ssocio-politicalocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed aass vvillageillage ffoolool ● TThehe nnoiroir wworldorld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ooff IIranianranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred DDefence’efence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar FFarhadi’sarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew ddiasporiciasporic visionsvisions ooff IIranran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews aandnd eeventsvents -

Samuel Khachikian and the Rise and Fall of Iranian Genre Films

Samuel Khachikian and the Rise and Fall of Iranian Genre Films he films of Samuel Khachikian have, as the director’s name suggests, a strange ambiguity. One of the father figures of Iranian cinema, Khachikian was for 40 years synony- mous with popular genre films inspired by Hollywood and enjoyed by big audiences. His formal innovations and fluid handling of genres not only expanded the pos- sibilities of cinema in Iran, but reflected the specific social and political tensions of a country building to revolution. Ehsan Khoshbakht Hollywood style in modern Tehran In the 1950s and ’60s, the premieres of Khachikian’s films would cause traffic jams. Newly built cinemas opened with the latest Khachikian, who was dubbed the “Iranian Hitch- cock,” a title he disliked. Khachikian’s films provide us with images of a bygone era in Iran: Cadillacs roaring through the streets, women in skirts parading to the next house party, bars open until the small hours of the morning, dancers grooving to the swing of a modernized, post-coup Tehran—all soon to collapse into revolution. The films are part documentary, part product of Khachikian’s fantasy of an Iran that has successfully absorbed Hollywood style. The films were unique in the way in which they could almost be passed off as foreign productions. His classic Mid- night Terror (1961) was reportedly bought and dubbed by the Italians; with names changed, it’s as if the story had been set in Milan. Fully aware of the deep contradictions of this encounter between cultures, however, the films manifest a sense of unease. -

Taxi Teheran

PRESENTE / PRESENTEERT TAXI TEHERAN un film de et avec / een film van en met JAFAR PANAHI BERLINALE 2015 – GOLDEN BEAR & FIPRESCI PRIZE LUXEMBOURG CITY FILM FESTIVAL 2015 – AUDIENCE AWARD MOOOV 2015 Iran – 2015 – DCP – couleur / kleur – 1:1.85 – 5.1 – VO ST BIL / OV FR/NL OT – 82’ distribution / distributie: IMAGINE SORTIE NATIONALE RELEASE 22/04/2015 T : 02 331 64 31 / F : 02 331 64 34 / M : 0499 25 25 43 photos / foto's : www.imaginefilm.be/PRO SYNOPSIS FR Installé au volant de son taxi, Jafar Panahi sillonne les rues animées de Téhéran. Au gré des passagers qui se succèdent et se confient à lui, le réalisateur dresse le portrait de la sociét iranienne entre rires et émotion. NL In TAXI TEHERAN zit Panahi zelf achter het stuur van een wagen, waarmee hij Teheran doorkruist en via gesprekken met z'n passagiers een kleurrijke mozaïek toont van het alledaagse leven in de Iraanse hoofdstad. EN A yellow cab is driving through the vibrant and colourful streets of Teheran. Very diverse passengers enter the taxi, each candidly expressing their views while being interviewed by the driver who is no one else but the director Jafar Panahi himself. His camera placed on the dashboard of his mobile film studio captures the spirit of Iranian society through this comedic and dramatic drive… “Limitations often inspire storytellers to make better work, but sometimes those limitations can be so suffocating they destroy a project and often damage the soul of the artist. Instead of allowing his spirit to be crushed and giving up, instead of allowing himself to be filled with anger and frustration, Jafar Panahi wrote a love letter to cinema. -

Festival Centerpiece Films

50 Years! Since 1965, the Chicago International Film Festival has brought you thousands of groundbreaking, highly acclaimed and thought-provoking films from around the globe. In 2014, our mission remains the same: to bring Chicago the unique opportunity to see world- class cinema, from new discoveries to international prizewinners, and hear directly from the talented people who’ve brought them to us. This year is no different, with filmmakers from Scandinavia to Mexico and Hollywood to our backyard, joining us for what is Chicago’s most thrilling movie event of the year. And watch out for this year’s festival guests, including Oliver Stone, Isabelle Huppert, Michael Moore, Taylor Hackford, Denys Arcand, Liv Ullmann, Kathleen Turner, Margarethe von Trotta, Krzysztof Zanussi and many others you will be excited to discover. To all of our guests, past, present and future—we thank you for your continued support, excitement, and most importantly, your love for movies! Happy Anniversary to us! Michael Kutza, Founder & Artistic Director When OCTOBEr 9 – 23, 2014 Now in our 50th year, the Chicago International Film Festival is North America’s oldest What competitive international film festival. Where AMC RIVER EaST 21* (322 E. Illinois St.) *unless otherwise noted Easy access via public transportation! CTA Red Line: Grand Ave. station, walk five blocks east to the theater. CTA Buses: #29 (State St. to Navy Pier), #66 (Chicago Red Line to Navy Pier), #65 (Grand Red Line to Navy Pier). For CTA information, visit transitchicago.com or call 1-888-YOUR-CTA. Festival Parking: Discounted parking available at River East Center Self Park (lower level of AMC River East 21, 300 E. -

Religious Studies 181B Political Islam and the Response of Iranian

Religious Studies 181B Political Islam and the Response of Iranian Cinema Fall 2012 Wednesdays 5‐7:50 PM HSSB 3001E PROFESSOR JANET AFARY Office: HSSB 3047 Office Hours; Wednesday 2:00‐3:00 PM E‐Mail: [email protected] Assistant: Shayan Samsami E‐Mail: [email protected] Course Description Artistic Iranian Cinema has been influenced by the French New Wave and Italian neorealist styles but has its own distinctly Iranian style of visual poetry and symbolic lanGuaGe, brinGinG to mind the delicate patterns and intricacies of much older Iranian art forms, the Persian carpet and Sufi mystical poems. The many subtleties of Iranian Cinema has also stemmed from the filmmakers’ need to circumvent the harsh censorship rules of the state and the financial limitations imposed on independent filmmakers. Despite these limitations, post‐revolutionary Iranian Cinema has been a reGular feature at major film festivals around the Globe. The minimalist Art Cinema of Iran often blurs the borders between documentary and fiction films. Directors employ non‐professional actors. Male and female directors and actors darinGly explore the themes of Gender inequality and sexual exploitation of women in their work, even thouGh censorship laws forbid female and male actors from touchinG one another. In the process, filmmakers have created aesthetically sublime metaphors that bypass the censors and directly communicate with a universal audience. This course is an introduction to contemporary Iranian cinema and its interaction with Political Islam. Special attention will be paid to how Iranian Realism has 1 developed a more tolerant discourse on Islam, culture, Gender, and ethnicity for Iran and the Iranian plateau, with films about Iran, AfGhanistan, and Central Asia. -

FISH Newsletter November 16

Tehran Taxi (Iran 2015) DIRECTOR : Jafar Panahi RUNNING TIME : 82mins RATING : Documentary Synopsis: Banned Iranain director Jafar Panahi takes to the streets of Tehran in a taxi with his camera secreted on the cab’s dashboard. Winner of the Golden Bear Berlin Film Festival 2015 Review:Jonathan Romney Much loose talk is bandied around in the film world about directors’ bravery and the heroism of “guerrilla” film-making – but those terms genuinely mean something when applied to Iran’s Jafar Panahi. After making several robust realist dramas about the challenges of everyday life in his country – among them The Circle, Crimson Gold and the exuberantly angry football movie Offside – Panahi fell foul of the Iranian government, which threatened him with imprisonment, prevented him from travelling and banned him from making films for 20 years. He has protested by working under the wire to make three extraordinary works, contraband statements that are at once a cri de coeur from internal exile, and a bring-it-on raised fist of defiance. This Is Not a Film (2011, directed with Mojtaba Mirtahmasb) showed Panahi cooling his heels under house arrest in his Tehran flat, and evoking the film that he would have made had he been allowed to pick up a camera. He wasn’t technically making an actual film, Panahi argued – yet he was manifestly making one anyway, as the world saw when the result was smuggled to Cannes on a USB stick hidden in a cake. However, the less successful Closed Curtain (2013, directed with Kambuzia Partovi) was a claustrophobically self-referential chamber piece, and suggested that Panahi’s plight was getting the better of him. -

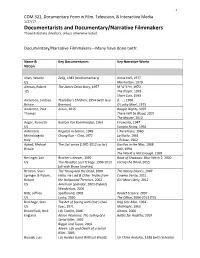

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

The Sand Canyon Review 2013

The Sand Canyon Review 2013 1 Dear Reader, The Sand Canyon Review is back for its 6th issue. Since the conception of the magazine, we have wanted to create an outlet for artists of all genres and mediums to express their passion, craft, and talent to the masses in an accessible way. We have worked especially hard to foster a creative atmosphere in which people can express their identity through the work that they do. I have done a lot of thinking about the topic of identity. Whether someone is creating a poem, story, art piece, or multimedia endeavor, we all put a piece of ourselves, a piece of who we are into everything we create. The identity of oneself is embedded into not only our creations but our lives. This year the goal ofThe Sand Canyon Review is to tap into this notion, to go beyond the words on a page, beyond the color on the canvas, and discover the artist behind the piece. This magazine is not only a collection of different artists’ identities, but it is also a part of The Sand Canyon Review team’s identity. On behalf of the entire SCR staff, I wish you a wonderful journey into the lives of everyone represented in these pages. Sincerely, Roberto Manjarrez, Managing Editor MANAGING EDITOR Roberto Manjarrez POETRY SELectION TEAM Faith Pasillas, Director Brittany Whitt Art SELectION TEAM Mariah Ertl, Co-Director Aurora Escott, Co-Director Nicole Hawkins Christopher Negron FIT C ION SELectION TEAM Annmarie Stickels, Editorial Director BILL SUMMERS VICTORIA CEBALLOS Nicole Hakim Brandon Gnuschke GRAphIC DesIGN TEAM Jillian Nicholson, Director Walter Achramowicz Brian Campell Robert Morgan Paul Appel PUBLIC RELATIONS The SCR STAFF COPY EDITORS Bill Summers Nicole Hakim COVER IMAGE The Giving Tree, Owen Klaas EDITOR IN CHIEF Ryan Bartlett 2013 EDITION3 Table of Contents Poetry Come My Good Country You Know 8 Mouse Slipping Through the Knot I Saw Sunrise From My Knees 10 From This Apartment 12 L. -

May 2014 at BFI Southbank

May 2014 at BFI Southbank Hollywood Babylon, Walerian Borowczyk, Studio Ghibli, Anime Weekend, Edwardian TV Drama, Sci-Fi-London 2014 Hollywood Babylon: Early Talkies Before the Censors is the new Sight & Sound Deep Focus, looking at the daring, provocative and risqué films from the 1930s that launched the careers of cinema luminaries such as Bette Davis, Clark Gable, Barbara Stanwyck and Spencer Tracy. The Passport to Cinema strand continues this scintillating exploration until the end of July Cinema of Desire: The Films of Walerian Borowczyk is the first major UK retrospective of works from the infamous director of The Beast (La Bête, 1975). BFI Southbank joins forces with the 12th Kinoteka Polish Film Festival to present this programme, which will also feature a dedicated event featuring friends and colleagues of the artist on 18 May The concluding part of the Studio Ghibli retrospective, and 30th anniversary celebration, will screen well-loved family favourites including Princess Mononoke (1997), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) and Ponyo (2008), to complement the release of Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises (2013), on 9 May The biennial BFI Southbank .Anime Weekend returns with some of the best anime to come out of Japan; this year’s selection boasts three UK premieres, including Ghost in the Shell Arise: Part 2: Ghost Whispers (2013), plus the European premiere of Tiger and Bunny: The Rising (2014) As a prelude to our WWI season in June, Classics on TV: Edwardian Drama on the Small Screen look at the plays which reveal the social