The Deterioration of Gates and Arnold's Relationship at Saratoga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Valcour_Island Coordinates: 44°36′37.84″N 73°25′49.39″W From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The naval Battle of Valcour Island, also known as the Battle of Valcour Bay, took place on October 11, 1776, on Battle of Valcour Island Lake Champlain. The main action took place in Valcour Part of the American Revolutionary War Bay, a narrow strait between the New York mainland and Valcour Island. The battle is generally regarded as one of the first naval battles of the American Revolutionary War, and one of the first fought by the United States Navy. Most of the ships in the American fleet under the command of Benedict Arnold were captured or destroyed by a British force under the overall direction of General Guy Carleton. However, the American defense of Lake Champlain stalled British plans to reach the upper Hudson River valley. The Continental Army had retreated from Quebec to Fort Royal Savage is shown run aground and burning, Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point in June 1776 after while British ships fire on her (watercolor by British forces were massively reinforced. They spent the unknown artist, ca. 1925) summer of 1776 fortifying those forts, and building additional ships to augment the small American fleet Date October 11, 1776 already on the lake. General Carleton had a 9,000 man Location near Valcour Bay, Lake Champlain, army at Fort Saint-Jean, but needed to build a fleet to carry Town of Peru / Town of Plattsburgh, it on the lake. -

The Time Trial of Benedict Arnold 1 National Museum of American History

The Time Trial of Benedict Arnold 1 National Museum of American History The Time Trial of Benedict Arnold Purpose By debating the legacy of Benedict Arnold, students will build reasoning and critical thinking skills and an understanding of the complexity of historical events and historical memory. Program Summary In this presentation, offered as a public program at the National Museum of American History from December 2010-April 2011, an actor portrays a fictionalized Benedict Arnold, hero and villain of the American Revolution. Arnold, in dialogue with an audience that is facilitated by an arbiter, discusses his notable actions at the Battle of Saratoga and at Valcour Island, as well as his decision to sell the plans for West Point to the British. At the conclusion of the program, audience members consider how history should remember Arnold, as a traitor, or as a hero. This set of materials is designed to provide you an opportunity to have a similar debate with your students. Included in this resource set are a full video of the program, to be used as preparation for the classroom activity, and Arnold’s conversation with the audience divided by theme, to be used with the resources offered below for your own Time Trial of Benedict Arnold. A full version of the program is available here. [https://vimeo.com/129257467] Grade levels 5-8 Time Three 45 minute periods National Standards National Center for History in the Schools: United States History Standards; Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s); Standard 2: The impact of the American Revolution on politics, economy, and society Common Core Standards for Literacy in History and Social Studies: Speaking and Listening Standards Comprehension and Collaboration, standard 1: Grades 6-8: Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher- led) with diverse partners on grade level topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly. -

S39479 William Eastin

Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters Pension Application of William Eastin S39479 VA Transcribed and annotated by C. Leon Harris. District of Virginia At a Court continued and held for Albemarle County the third day of November, one thousand eight hundred and eighteen, William Eastin personally appeared in court aged sixty one years a resident of the said County of Albemarle and being first duly sworn according to law, on oath doth make the following declaration in order to obtain the provisions made by the late Act of Congress entitled “An Act to provide for certain persons engaged in the land and naval service of the United States in the revolutionary war.” that he the said William Eastin enlisted in the aforesaid County of Albemarle, in the district aforesaid in the year 1776 in the company commanded by Capt. Reuben Taylor of Orange County belonging to the Regiment called Congress Regiment [AKA 2nd Canadian Regiment], commanded by Colo. Moses Hazen on the continental establishment; that he continued to serve as a sergeant, in the said Corps and in the service of the United States for the term of three years & five months when he was discharged from service, towit on the 19th of March 1780 in Maurice town [sic: Morristown] in the State of New Jersey, that he was in the battle of Staten Island [probably raid by Gen. John Sullivan, 21 Aug 1777], the battle of Brandy Wine [Brandywine, 11 Sep 1777], and the battle of Germantown [4 Oct 1777], in the division commanded by Major Gen’l. -

030321 VLP Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga readies for new season LEE MANCHESTER, Lake Placid News TICONDEROGA — As countered a band of Mohawk Iro- name brought the eastern foothills American forces prepared this quois warriors, setting off the first of the Adirondack Mountains into week for a new war against Iraq, battle associated with the Euro- the territory worked by the voya- historians and educators in Ti- pean exploration and settlement geurs, the backwoods fur traders conderoga prepared for yet an- of the North Country. whose pelts enriched New other visitors’ season at the site of Champlain’s journey down France. Ticonderoga was the America’s first Revolutionary the lake which came to bear his southernmost outpost of the War victory: Fort Ticonderoga. A little over an hour’s drive from Lake Placid, Ticonderoga is situated — town, village and fort — in the far southeastern corner of Essex County, just a short stone’s throw across Lake Cham- plain from the Green Mountains of Vermont. Fort Ticonderoga is an abso- lute North Country “must see” — but to appreciate this historical gem, one must know its history. Two centuries of battle It was the two-mile “carry” up the La Chute River from Lake Champlain through Ticonderoga village to Lake George that gave the site its name, a Mohican word that means “land between the wa- ters.” Overlooking the water highway connecting the two lakes as well as the St. Lawrence and Hudson rivers, Ticonderoga’s strategic importance made it the frontier for centuries between competing cultures: first between the northern Abenaki and south- ern Mohawk natives, then be- tween French and English colo- nizers, and finally between royal- ists and patriots in the American Revolution. -

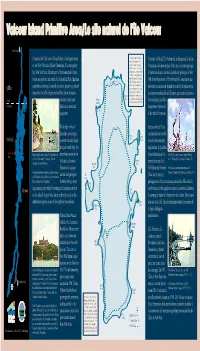

Valcour Primitive Area

Chambly Canal L’île Valcour comporte 12 km de Comprised of 1,100 acres, Valcour Island is the largest island sentiers de randonnée et 25 Couvrant 4,45 km2, l’île Valcour est la plus grande île du lac emplacements de camping on the New York side of Lake Champlain. It is managed by désignés. Des permis de camping Champlain, côté new-yorkais. Cette zone de nature protégée gratuits d’une durée maximale de the New York State Department of Environmental Conser- 14 jours sont émis par un gardien à l’intérieur du parc des Adirondacks est gérée par le New du parc. Par ailleurs, le site ayant vation as a primitive area within the Adirondack Park. Emphasis adopté le principe du premier York State Department of Environmental Conservation qui is placed on restoring its natural condition, preserving cultural arrivé, premier servi, aucune réser- préconise la restauration du milieu naturel et la préservation Quebec vation n’est acceptée. Pour de plus resources, and affording recreation that does not require amples renseignements sur l’île des ressources culturelles de l’île ainsi que les activités récréa- Beauty Valcour, veuillez communiquer Bay avec le Department of Environmen- Canada extensive man-made Valcour tives n’exigeant pas d’am- Landing tal Conservation au (518) 897-1200. United States facilities or motorized énagements importants equipment. ni de matériel motorisé. With eight miles of Avec sa côte de 13 km shoreline, consisting of constituée d’une variété Spoon Spoon New York a variety of rocky ledges Bay Island de corniches rocheuses and quiet sandy bays, the surplombant de paisibles You Are Here Boating along the rocky ledges of Valcour Island at the recreational potential on baies sablonneuses, le “Baby Blues,” similar to scenes found on Valcour Peru turn of the 19th century. -

22 AUG 2021 Index Acadia Rock 14967

19 SEP 2021 Index 543 Au Sable Point 14863 �� � � � � 324, 331 Belle Isle 14976 � � � � � � � � � 493 Au Sable Point 14962, 14963 �� � � � 468 Belle Isle, MI 14853, 14848 � � � � � 290 Index Au Sable River 14863 � � � � � � � 331 Belle River 14850� � � � � � � � � 301 Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Res- Belle River 14852, 14853� � � � � � 308 cue System (AMVER)� � � � � 13 Bellevue Island 14882 �� � � � � � � 346 Automatic Identification System (AIS) Aids Bellow Island 14913 � � � � � � � 363 A to Navigation � � � � � � � � 12 Belmont Harbor 14926, 14928 � � � 407 Au Train Bay 14963 � � � � � � � � 469 Benson Landing 14784 � � � � � � 500 Acadia Rock 14967, 14968 � � � � � 491 Au Train Island 14963 � � � � � � � 469 Benton Harbor, MI 14930 � � � � � 381 Adams Point 14864, 14880 �� � � � � 336 Au Train Point 14969 � � � � � � � 469 Bete Grise Bay 14964 � � � � � � � 475 Agate Bay 14966 �� � � � � � � � � 488 Avon Point 14826� � � � � � � � � 259 Betsie Lake 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agate Harbor 14964� � � � � � � � 476 Betsie River 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agriculture, Department of� � � � 24, 536 B Biddle Point 14881 �� � � � � � � � 344 Ahnapee River 14910 � � � � � � � 423 Biddle Point 14911 �� � � � � � � � 444 Aids to navigation � � � � � � � � � 10 Big Bay 14932 �� � � � � � � � � � 379 Baby Point 14852� � � � � � � � � 306 Air Almanac � � � � � � � � � � � 533 Big Bay 14963, 14964 �� � � � � � � 471 Bad River 14863, 14867 � � � � � � 327 Alabaster, MI 14863 � � � � � � � � 330 Big Bay 14967 �� � � � � � � � � � 490 Baileys -

The Battle of Saratoga to the Paris Peace Treaty

1 Matt Gillespie 12/17/03 A&HW 4036 Unit: Colonial America and the American Revolution. Lesson: The Battle of Saratoga to the Paris Peace Treaty. AIM: Why was the American victory at the Saratoga Campaign important for the American Revolution? Goals/Objectives: 1. Given factual data about the Battle of Saratoga and the Battle of Yorktown, students will be able to describe the particular events of the battles and how the Americans were able to win each battle. 2. Students will be able to recognize and explain why the battles were significant in the context of the entire war. (For example, the Battle of Saratoga indirectly leads to French assistance.) 3. Students will be able to read and interpret a key political document, The Paris peace Treaty of 1783. 4. Students will investigate key turning points in US history and explain why these events are significant. Students will be able to make arguments as to why these two battles were turning points in American history. (NYS 1.4) 5. Given the information, students will understand their historical roots and be able to reconstruct the past. Students will be able to realize how victory in these battles enabled the paris Peace Treaty to come about. (NCSS II) Main Ideas: • The campaign consists of three major conflicts. 1) The Battle of Freeman’s farm. 2) Battle of Bennington. 3) Battle of Bemis Heights. • Battle of Bennington took place on Aug. 16-17th, 1777. Burgoyne sent out Baum to take American stores at Bennington. General Stark won. • Freeman’s farm was on Sept. -

Inquiry – Benedict Arnold

Inquiry – Benedict Arnold Hook discussion question: What is betrayal? The discussion must touch on themes of loyalty and trust. Other themes may include ethics and morality. Hook visual: Presentation formula Previous Unit: The Revolutionary War will be in progress. Saratoga (1777) should have been covered. This Unit: Narrative story to present a skeletal overview of the events. Then introduce the documents, to add “muscle” to the events. Next Unit: The Revolutionary War topic will continue and be brought to conclusion. Post-Lesson Discussion prompts 1. How should we go about weighing the good someone does against the bad? At what point is one (good/bad) not balanced by the other? 2. After the war, for what reasons might the British trust or not trust Benedict Arnold? 3. In the years following the war, America tried to get England to hand over Benedict Arnold to American authorities. Should the British give him up? Why yes/no? 4. One thing missing from the discussion of betrayal and loyalty is the concept of regret. How might this relate to Arnold, Washington and others, and by what means might it be expressed? 5. How likely (or not) would it be today for one of America’s top Generals to engage in a similar traitorous act? 6. To what extent would it matter if it is a General betraying the country or a civilian acting in a traitorous manner…should these be viewed in a similar light? 7. To what extent can a person be trusted again once they have already broken your trust? 8. -

The Impact of Weather on Armies During the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Force of Nature: The Impact of Weather on Armies during the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T. Engel Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE FORCE OF NATURE: THE IMPACT OF WEATHER ON ARMIES DURING THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1775-1781 By JONATHAN T. ENGEL A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Jonathan T. Engel defended on March 18, 2011. __________________________________ Sally Hadden Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ Kristine Harper Committee Member __________________________________ James Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii This thesis is dedicated to the glory of God, who made the world and all things in it, and whose word calms storms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Colonies may fight for political independence, but no human being can be truly independent, and I have benefitted tremendously from the support and aid of many people. My advisor, Professor Sally Hadden, has helped me understand the mysteries of graduate school, guided me through the process of earning an M.A., and offered valuable feedback as I worked on this project. I likewise thank Professors Kristine Harper and James Jones for serving on my committee and sharing their comments and insights. -

Document Review and Archaeological Assessment of Selected Areas from the Revolutionary War and War of 1812

American Battlefield Protection Program Grant 2287-16-009: Document Review and Archaeological Assessment Document Review and Archaeological Assessment of Selected Areas from the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. Plattsburgh, New York PREPARED FOR: The City of Plattsburgh, NY, 12901 IN ACCORDANCE WITH REQUIREMENTS OF GRANT FUNDING PROVIDED THROUGH: American Battlefield Protection Program Heritage Preservation Services National Park Service 1849 C Street NW (NC330) Washington, DC 20240 (Grant 2287-16-009) PREPARED BY: 4472 Basin Harbor Road, Vergennes, VT 05491 802.475.2022 • [email protected] • www.lcmm.org BY: Cherilyn A. Gilligan Christopher R. Sabick Patricia N. Reid 2019 1 American Battlefield Protection Program Grant 2287-16-009: Document Review and Archaeological Assessment Abstract As part of a regional collaboration between the City of Plattsburgh, New York, and the towns of Plattsburgh and Peru, New York, the Maritime Research Institute (MRI) at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum (LCMM) has been chosen to investigate six historical Revolutionary War and War of 1812 sites: Valcour Island, Crab Island, Fort Brown, Fort Moreau, Fort Scott, and Plattsburgh Bay. These sites will require varying degrees of evaluation based upon the scope of the overall heritage tourism plan for the greater Plattsburgh area. The MRI’s role in this collaboration is to conduct a document review for each of the six historic sites as well as an archaeological assessment for Fort Brown and Valcour Island. The archaeological assessments will utilize KOCOA analysis outlined in the Battlefield Survey Manual of the American Battlefield Protection Program provided by the National Park Service. This deliverable fulfills Tasks 1 and 3 of the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) Grant 2887-16-009. -

The Revolution Part 7 Guide.Pdf

THE HISTORY CHANNEL® PRESENTS The Revolution: Treason and Betrayal Part 7 of a 13 part original series The American Revolution laid the foundation for the success of the United States, yet the viability of the nation was not always imminent and the quest for liberty was no simple endeavor. As the Colonists found themselves becoming increasingly independent, the fiercest and most powerful army in the world stood between them and a free, independent, sovereign America. Small skirmishes between colonists and representatives of the British throne escalated in 1775. In order to pacify what he viewed as a small rebellion, the King sent a contingent of Red Coats from the seemingly omnipotent British Army across the Atlantic Ocean. However, as the days and months progressed, the Red Coats, their military leaders and King George III himself eventually realized the ferocity, courage and collective will of the colonists they faced. The Revolution: Treason and Betrayal begins on July 4th, 1778, the second anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and a day of celebration for the Continental soldiers. Having proven their mettle at the Battle of Monmouth, the soldiers and their general, George Washington, have a renewed sense of confidence. The following year, however, will test the strength and patience of this army. Rumors of treason, the added threat of the Iroquois Nation, and the failure of the French Fleet to successfully reach the Colonies all serve to weaken the Continental Army. How will Washington maintain morale and recruit new soldiers against this adversity? Curriculum Links The Revolution: Treason and Betrayal would be useful for high school and middle school classes on United States History, Military History, European History, and Colonial History. -

W7716 James Heaton

Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements and Rosters Pension Application of James Heaton W7716 Elizabeth Heaton MD Transcribed and annotated by C. Leon Harris. Commonwealth of Penns’a. Berks County Ss. On the seventeenth day of April A.D. 1818 before the Judges of the Court of Common Pleas of the said County personally appeared in open Court James Heaton of the borough of Reading in the said County, who being duly sworn did depose and say that he enlisted in the service of the United States at Baltimore with Capt. McConnel [sic: Nathan McConnell] of Col. Hazens Regiment [Moses Hazen’s 2nd Canadian Regiment] in the beginning of January A.D. 1778 That he continued in the service of the United States until the 13th day of June 1783, when he was honourably discharged: That he was wounded at the seige of Yorktown in Virginia in storming a redoubt [Redoubt 10, 14 Oct 1781] – that he has not received any pension under the laws of the United States and that by reason of his reduced circumstances he stands in need of assistance from his Country. James hisXmark Heaton BY HIS EXCELLENCY GEORGE WASHINGTON, Esq, General and Commander in Chief of the Forces of the United States of America. THESE are to CERTIFY that the Bearer hereof Corp’l. James Heaton, Soldier, from the State of Maryland in the General Hazen’s Regiment, having faithfully served the United States five year six months and being inlisted for the War only, is hereby DISCHARGED from the American Army. GIVEN at HEAD-QUARTERS [at Newburgh NY] the 13th of June 1783.