Changing Perspectives in Australian Archaeology, Part III. Hidden in Plain View—The Sydney Aboriginal Historical Places Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cooks River Valley Association Inc. PO Box H150, Hurlstone Park NSW 2193 E: [email protected] W: ABN 14 390 158 512

Cooks River Valley Association Inc. PO Box H150, Hurlstone Park NSW 2193 E: [email protected] W: www.crva.org.au ABN 14 390 158 512 8 August 2018 To: Ian Naylor Manager, Civic and Executive Support Leichhardt Service Centre Inner West Council 7-15 Wetherill Street Leichhardt NSW 2040 Dear Ian Re: Petition on proposal to establish a Pemulwuy Cooks River Trail The Cooks River Valley Association (CRVA) would like to submit the attached petition to establish a Pemulwuy Cooks River Trail to the Inner West Council. The signatures on the petition were mainly collected at two events that were held in Marrickville during April and May 2018. These events were the Anzac Day Reflection held on 25 April 2018 in Richardson’s Lookout – Marrickville Peace Park and the National Sorry Day Walk along the Cooks River via a number of Indigenous Interpretive Sites on 26 May 2018. The purpose of the petition is to creatively showcase the history and culture of the local Aboriginal community along the Cooks River and to publicly acknowledge the role of Pemulwuy as “father of local Aboriginal resistance”. The action petitioned for was expressed in the following terms: “We, the undersigned, are concerned citizens who urge Inner West Council in conjunction with Council’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Reference Group (A&TSIRG) to designate the walk between the Aboriginal Interpretive Sites along the Cooks River parks in Marrickville as the Pemulwuy Trail and produce an information leaflet to explain the sites and the Aboriginal connection to the Cooks River (River of Goolay’yari).” A total of 60 signatures have been collected on the petition attached. -

The Founding of Aboriginal History and the Forming of Aboriginal History

The founding of Aboriginal History and the forming of Aboriginal history Bain Attwood Nearly 40 years ago an important historical project was launched at The Australian National University (ANU). It came to be called Aboriginal history. It was the name of both a periodical and a historiographical movement. In this article I seek to provide a comprehensive account of the founding of the former and to trace something of the formation of the latter.1 Aboriginal history first began to be formed in the closing months of 1975 when a small group of historically-minded white scholars at ANU agreed to found what they described as a journal of Aboriginal History. At that time, the term, let alone the concept of Aboriginal history, was a novel one. The planners of this academic journal seem to have been among the first to use the phrase in its discursive sense when they suggested that it ‘should serve as a publications outlet in the field of Aboriginal history’.2 Significantly, the term was adopted in the public realm at much the same time. The reports of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (the Pigott Report) and the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, which were the outcome of an inquiry commissioned by the Whitlam Labor Government in order to articulate and give expression to a new Australian nationalism by championing a past that was indigenous to the Australian continent, both used the term.3 As 1 I wish to thank Niel Gunson, Bob Reece and James Urry for allowing me to view some of their personal -

Australian Aboriginal Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australian Aboriginal Art Patrick Hutchings To attack one’s neighbours, to pass or to crush and subdue more remote peoples without provocation and solely for the thirst for dominion—what is one to call it but brigandage on a grand scale?1 The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo, IV Ch 6 ‘The natives are extremely fond of painting and often sit hours by me when at work’ 2 Thomas Watling The Australians and the British began their relationship by ‘dancing together’, so writes Inge Clendinnen in her multi-voiced Dancing With Strangers 3 which weaves contemporary narratives of Sydney Cove in 1788. The event of dancing is witnessed to by a watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley, ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales March 1788’, which is reproduced by Clendinnen as both a plate and a dustcover.4 By ‘The Australians’ Clendinnen means the Aboriginal pop- ulation. But, of course, Aboriginality is not an Aboriginal concept but an Imperial one. As Sonja Kurtzer writes: ‘The concept of Aboriginality did not even exist before the coming of the European’.5 And as for the terra nullius to which the British came, it was always a legal fiction. All this taken in, one sees why Clendinnen calls the First People ‘The Australians’, leaving most of those with the current passport very much Second People. But: winner has taken, almost, all. The Eddie Mabo case6 exploded terra nullius, but most of the ‘nobody’s land’ now still belongs to the Second People. -

Contents What’S New

September / October, No. 5/2011 CONTENTS WHAT’S NEW Two Suggestions About How To Make Cultural Heritage Win a free registration to the Materials Available .................................................................... 2 2012 Native Title Conference! Workshop Series: Thresholds for Traditional Owner Settlements in Victoria .............................................................. 4 Just take 5 minutes to complete our publications survey and you will go into the Foundations of the Kimberley Aboriginal Caring for Country Plan — Bungarun and the Kimberley Aboriginal Reference draw to win a free registration to the 2012 Group .......................................................................................... 5 Native Title Conference. The winner will be announced in January, 2012. ‘Anthropologies of Change: Theoretical and Methodological Challenges’ Workshop .............................................................. 8 CLICK HERE TO COMPLETE THE From Mississippi to Broome – Creating Transformative SURVEY Indigenous Economic Opportunity ........................................ 10 What’s New ............................................................................... 11 If you have any questions or concerns, please Native Title Publications ......................................................... 19 contact Matt O’Rourke at the Native Title Research Unit on (02) 6246 1158 or Native Title in the News ........................................................... 19 [email protected] Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) -

Conference Program: Tuesday, 27Th August 2019

Conference Program: Tuesday, 27th August 2019 12:00 pm – Trade Exhibition Bump In 5:00 pm Welcome BBQ 5:30 pm – Venue: Betting Tee Lawns, Pacific Bay Resort 7:00 pm Dress Code: Wear your tackiest Hawaiian shirt! Conference Program: Wednesday, 28th August 2019 7:30 am – Stormwater NSW Annual General Meeting 8:30 am All current members of Stormwater NSW are welcome to join 8:00 am Conference Registration – Tea and Coffee on Arrival Reef Room 8:45 am – Welcome and Housekeeping 8:55 am Beth Salt, Convenor, 2019 Stormwater NSW Conference 8:55 am – Welcome to Country 9:00 am Uncle Mark, Gumbaynggirr Elder 9:00 am – Official Conference Opening 9:05 am Cr Denise Knight, Mayor, Coffs Harbour City Council 9:05 am – Keynote Address: Wither NSW Sustainable Stormwater Practices – Rural NSW Experiences 9:50 am Greg Mashiah, Clarence Valley Council Keynote Address: How Successful Are Local Government Waste Abatement Strategies at 9:50 am – Reducing Plastic Waste into The Coastal Environment? 10:35 am Kathy Willis, University of Tasmania and CSIRO 10:35 am – Morning Tea and Trade Exhibition 11:10 am Marina Room Harbour Room Jetty Room Technical Marvel Failure to Thrive Urban Waterway Syndrome 11:10 am – What Comes Before The Impact of Procurement The Advantage of Detention 11:20 am MUSIC? Considering Processes on Sustainable Basins with Outflow Rate Landscape Restrictions as a Water Cycle Management Above Existing Condition: Prelude to Outcomes for Greenfield Case Study Western Sydney Implementing/Conceptually Development Aerotropolis Modelling WSUD -

Estuary Surveillance for QX Disease

Estuary surveillance Student task sheet for QX disease The following tables show data collected Estuary Surveillance 2002: during estuary surveillance from 2001– During the 2002 sampling period a total of 2004 for New South Wales and 5250 oysters were received and processed Queensland. N is the number of oysters from 18 NSW estuaries and three tested in a random sample of the oyster Queensland zones using tissue imprints. population. Dr Adlard used two methods of disease detection in surveillance — tissue imprint and PCR. Table 2A: Tissue imprints used to detect the QX disease parasite Estuary Surveillance 2001: 2002 Survey results Table 1: Tissue imprint results for 2001 N 2001 Survey Results Estuary N infected % N Northern Moreton Bay 250 0 0 Estuary N infected % Central Moreton Bay 250 0 0 Tweed River 316 0 0 Southern Moreton Bay 250 2 0.8 Brunswick River 320 0 0 Tweed River 250 0 0 Richmond River 248 0 0 Brunswick River 250 0 0 Clarence River 330 5 1.52 Richmond River 250 102 40.8 Wooli River 294 0 0 Clarence River 250 55 22 Kalang /Bellinger 295 0 0 Wooli River 250 0 0 Rivers Kalang /Bellingen Rivers 250 0 0 Macleay River 261 0 0 Macleay River 250 0 0 Hastings River 330 0 0 Hastings River 250 0 0 Manning River 286 0 0 Manning River 250 0 0 Wallis Lakes 271 0 0 Wallis Lakes 250 0 0 Port Stephens 263 0 0 Port Stephens 250 0 0 Hawkesbury River 323 0 0 Hawkesbury River 250 0 0 Georges River 260 123 47.31 Georges River 250 40 16 Shoalhaven/ 255 0 0 Crookhaven Shoalhaven/Crookhaven 250 0 0 Bateman's Bay 300 0 0 Bateman's Bay 250 0 0 Tuross Lake 304 0 0 Tuross Lake 250 0 0 Narooma 300 0 0 Narooma 250 0 0 Merimbula 250 0 0 Merimbula 250 0 0 © Queensland Museum 2006 Table 2B: PCR results from 2002 on Estuary Surveillance 2003: oysters which had tested negative to QX During 2003 a total of 4450 oysters were disease parasite using tissue imprints received and processed from 22 NSW estuaries and three Queensland zones. -

Appendix 3 – Maps Part 5

LEGEND LGAs Study area FAIRFIELD LGA ¹ 8.12a 8.12b 8.12c 8.12d BANKSTOWN LGA 8.12e 8.12f 8.12i ROCKDALE LGA HURSTVILLE LGA 8.12v 8.12g 8.12h 8.12j 8.12k LIVERPOOL LGA NORTH BOTANY BAY CITY OF KOGARAH 8.12n 8.12o 8.12l 8.12m 8.12r 8.12s 8.12p 8.12q SUTHERLAND SHIRE 8.12t 8.12u COORDINATE SCALE 0500 1,000 2,000 PAGE SIZE FIG NO. 8.12 FIGURE TITLE Overview of Site Specific Maps DATE 17/08/2010 SYSTEM 1:70,000 A3 © SMEC Australia Pty Ltd 2010. Meters MGA Z56 All Rights Reserved Data Source - Vegetation: The Native Vegetation of the Sydney Metropolitan Catchment LOCATION I:Projects\3001765 - Georges River Estuary Process Management Authority Area (Draft) (2009). NSW Department of Environment, Climate Change PROJECT NO. 3001765 PROJECT TITLE Georges River Estuary Process Study CREATED BY C. Thompson Study\009 DATA\GIS\ArcView Files\Working files and Water. Hurstville, NSW Australia. LEGEND Weed Hotspot Priority Areas Study Area LGAs Riparian Vegetation & EEC (Moderate Priority) Riparian Vegetation & EEC (High Priority) ¹ Seagrass (High Priority) Saltmarsh (High Priority) Estuarine Reedland (Moderate Priority) Mangrove (Moderate Priority) Swamp Oak (Moderate Priority) Mooring Areas River Area Reserves River Access Cherrybrook Park Area could be used for educational purposes due to high public usage of the wharf and boat launch facilities. Educate on responsible use of watercraft, value of estuarine and foreshore vegetation and causes and outcomes of foreshore FAIRFIELD LGA erosion. River Flat Eucalypt Forest Cabramatta Creek (Liverpool LGA) - WEED HOT SPOT Dominated by Balloon Vine (Cardiospermum grandiflorum) and River Flat Eucalypt Forest Wild Tobacco Bush (Solanum mauritianum). -

NAIDOC Week 2021

TEACHER GUIDE YEARS F TO 10 NAIDOC Week 2021 Warning – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers and students are advised that this curriculumresource may contain images, voices or names of deceased people. Glossary Terms that may need to be introduced to students prior to teaching the resource: ceded: to hand over or give up something, such as land, to someone else. First Nations people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. NAIDOC: (acronym) National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee. NAIDOC Week: a nationally recognised week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. All Australians are invited to participate. sovereignty: supreme authority and independent power claimed or possessed by a community or state to govern itself or another state. Resource overview Introduction to NAIDOC Week – A history of protest and celebration NAIDOC Week is usually celebrated in the first full week of July. It’s a week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of First Nations people. Although NAIDOC Week falls in the mid-year school holidays, the aim of each theme isn’t limited to those set dates. Schools are encouraged to recognise and celebrate NAIDOC Week at any time throughout the year to ensure this important event isn’t overlooked. Themes can be incorporated as part of school life and the school curriculum. NAIDOC stands for ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’, the committee responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week. Its acronym has now become the name of the week. NAIDOC Week has a long history beginning with the human rights movement for First Nations Peoples in the 1920s. -

The March 1978 Flood on the Hawkesbury and Nepean

... I'., The March, 1978 flood on the Hawkesbury and Nepean River between Penrith and Pitt Town S. J. Riley School of Earth Sciences, Macquarie University, - North Ryde. N. S.W. 2113 .. ,.. ... .. ... ..... .. - ~ . .. '~,i';~;: '~ It'i _:"to "\f',. .,.,. ~ '.! . I .... I ,', ; I I ' }, I , I , I The March, 1978 flood on the I Hawkesbury and Nepean River I .. between PenDth and Pitt Town I I I I S.J. Riley 1 f I :''',i I I School of Earth Sciences, I Macquarie University, ·1 North Ryde. N.S.W. 2113 I I',.. , ··1 " " ., ~: ". , r-~.I··_'~ __'_'. ~ . '.," '. '..a.w-.,'",' --~,~"; l .' . - l~' _I,:.{·_ .. -1- Introduction As a result of three days of heavy rainfall over the Hawkesbury c:ltchment in March, 1978 floods occurred on all the streams in the Hawkesbury system. These floods caused considerable property damage and resulted in morphological changes to the channels and floodplains 1 of, the Hawkesbury system. This paper describes the flodd in the Hawkesbury-Nepean system in the reach'extending from Penrith to Pitt Town •. Storm Pattern An intense low pressure cell developed over the Coral Sea on the 16th March, 1978. This low pressure system travelled southeast towards the Queensland coast and gained in intensity (Fig.l). On the 18th March it,appeared that the cell would move eastwards away from Australia. However, the system reversed its direction of travel and moved inland. Resultant wind systems brought warm moist air from ,the east onto the .. " coast of New South Wal,es. Consequently, heavy rainfall$ occurred from f I .. the 18th to 24th March over the whole of eastern New South Wales. -

Extraction of Sand from the Colo River and Processing of Sand on Portion 37, Lower Colo Road, Colo

.. ";0Cl4 ~ /,blf/(' Report to the Honourable Bob Carr Minister for Planning and Environment An Inquiry pursuant to Section 119 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act, 1979, into a development application EXTRACTION OF SAND FROM THE COLO RIVER AND PROCESSING OF SAND ON PORTION 37, LOWER COLO ROAD, COLO John Woodward, Chairman COMMISSIONER OF INQUIRY September 1985 f \, F i i S Y D N E Y ,:j it September 1985 ( !'. 1, . TO MINISTER FOR PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENT j \ On 18th January 1985, you directed that an inquiry be ,I. '/ held in accordance with Section 119 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979, by a Commission of Inquiry ( with respect to a development application to dredge sand from the Colo River adjacent to portion 37, Lower Colo, in the Shire of Hawkesbury. You commissioned me to conduct ) the inquiry into the proposed development and to report \., my findings and recommendations to you . The public inquiry was held at Sydney commencing on 30th July, 1985. During the course of the inquiry adjournments were granted to allow certain parties further time to prepare their submissions to the inquiry. Field visits were conducted in the presence of the parties to the proposed dredging site on the Colo River, to adjoin ing lands and to nearby properties held by obj ectors to the development and to other vantage points in the area. The public sessions of the inquiry concluded on 14th August 1985. This report is made to you pursuant to the provisions of the Act and sets ")tit my findings and recommendations on the issues raised ,during the course of the inquiry. -

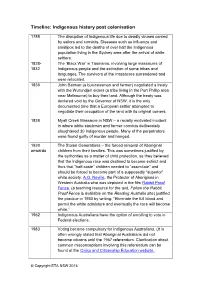

Indigenous History Post Colonisation

Timeline: Indigenous history post colonisation 1788 The disruption of Indigenous life due to deadly viruses carried by sailors and convicts. Diseases such as influenza and smallpox led to the deaths of over half the Indigenous population living in the Sydney area after the arrival of white settlers. 1828- The ‘Black War’ in Tasmania, involving large massacres of 1832 Indigenous people and the extinction of some tribes and languages. The survivors of the massacres surrendered and were relocated. 1835 John Batman (a businessman and farmer) negotiated a treaty with the Wurundjeri elders (a tribe living in the Port Phillip area near Melbourne) to buy their land. Although the treaty was declared void by the Governor of NSW, it is the only documented time that a European settler attempted to negotiate their occupation of the land with its original owners. 1838 Myall Creek Massacre in NSW – a racially motivated incident in where white stockmen and former convicts deliberately slaughtered 30 Indigenous people. Many of the perpetrators were found guilty of murder and hanged. 1930 The Stolen Generations – the forced removal of Aboriginal onwards children from their families. This was sometimes justified by the authorities as a matter of child protection, as they believed that the Indigenous race was destined to become extinct and thus that “half-caste” children needed to “assimilate” and should be forced to become part of a supposedly “superior” white society. A.O. Neville, the Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia who was depicted in the film Rabbit Proof Fence, (a teaching resource for the text, Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence is available on the Reading Australia site) justified the practice in 1930 by writing: “Eliminate the full blood and permit the white admixture and eventually the race will become white.” 1962 Indigenous Australians have the option of enrolling to vote in Federal elections. -

Hobby's Outreach

HOBBY'S OUTREACH Newsletter ef: BLUE MOUNTAINS HISTORICAL SOCIETY Inc. ISSN 1835-3010 P 0Box17, WENT\VORTH FAILS NSW 2782 Telephone: (02) 4757 3824 Hobby's Reach, 99 Blaxland Road, Wentworth Falls, NSW Email: [email protected] !Volume 20 Number3 August - September 20081 5 APRIL 2008 MEETING Contributed lry Colin Slade Continued from June-July issue The Garden Palace and The International Exhibition Sydney 1879 ,,,,":(a, -i-e-c-e-14~ 'f 111-i:J,'l"fll, !""""""'"" ,.,,1,7(e-~ During the first three days of the Exhibition some eighteen thousand visitors (excluding exhibitors and officials) passed -.... through the gates and an uneasy doubt was felt among the Commissioners as to the popular appeal of the Show. But Saturday 27 September, the first 'Shilling Day', banished all apprehension as 30,000 visitors crowded the Garden Palace and applauded a repeat performance of the Exhibition Cantata and the Hallelujah Chorus. The Sydney tram system owes its origins to the Exhibition. The first tram lines were laid from the nearest railway station at Redfern to Hunter Street to bring visitors in a double-decked carriage driven by a newly built steam tram. After the Exhibition this tram line was doubled all the way and extended to the eastern, southern and western suburbs. Among the many exhibits, only to name but a few from all over the world, included a Turkish Bazaar, Japanese Tea House, 116 samples of tea from different countries, Emerson's Oyster Saloon, a Maori House, Austro-Hungarian Wme and Beer Tasting Hall. A Fijian house, for a time inhabited by dancing natives claiming to have been cannibals, The Australian Dairy (a glass of fresh, cold milk for a penny), 20 kingdoms, republics and colonies were represented.