Joule 2.0 Supercomputer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3.Joule's Experiments

The Force of Gravity Creates Energy: The “Work” of James Prescott Joule http://www.bookrags.com/biography/james-prescott-joule-wsd/ James Prescott Joule (1818-1889) was the son of a successful British brewer. He tinkered with the tools of his father’s trade (particularly thermometers), and despite never earning an undergraduate degree, he was able to answer two rather simple questions: 1. Why is the temperature of the water at the bottom of a waterfall higher than the temperature at the top? 2. Why does an electrical current flowing through a conductor raise the temperature of water? In order to adequately investigate these questions on our own, we need to first define “temperature” and “energy.” Second, we should determine how the measurement of temperature can relate to “heat” (as energy). Third, we need to find relationships that might exist between temperature and “mechanical” energy and also between temperature and “electrical” energy. Definitions: Before continuing, please write down what you know about temperature and energy below. If you require more space, use the back. Temperature: Energy: We have used the concept of gravity to show how acceleration of freely falling objects is related mathematically to distance, time, and speed. We have also used the relationship between net force applied through a distance to define “work” in the Harvard Step Test. Now, through the work of Joule, we can equate the concepts of “work” and “energy”: Energy is the capacity of a physical system to do work. Potential energy is “stored” energy, kinetic energy is “moving” energy. One type of potential energy is that induced by the gravitational force between two objects held at a distance (there are other types of potential energy, including electrical, magnetic, chemical, nuclear, etc). -

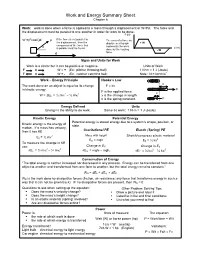

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Active Short Circuit - Chassis Short Characterization and Potential Mitigation Technique for the MMRTG

Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Multi-Mission RTG Active Short Circuit - Chassis Short Characterization and Potential Mitigation Technique for the MMRTG February 25, 2015 Gary Bolotin1 Nicholas Keyawa1 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology 1 Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Agenda Multi-Mission RTG • Introduction – MMRTG – Internal MMRTG Chassis Shorts • Active Short Circuit Purpose • Active Short Circuit Theory • Active Short Design and Component Layout • Conclusion and Future Work 2 Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Introduction – MMRTG Multi-Mission RTG • The Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG) utilizes a combination of PbTe, PbSnTe, and TAGS thermoelectric couples to produce electric current from the heat generated by the radioactive decay of plutonium – 238. 3 Jet Propulsion Laboratory Introduction – Internal MMRTG Chassis California Institute of Technology Shorts Multi-Mission RTG • Shorts inside the MMRTG between the electrical power circuit and the MMRTG chassis have been detected via isolation checks and/or changes in the bus balance voltage. • Example location of short shown below MMRTG Chassis Internal MMRTG Short 4 Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Active Short Circuit Purpose Multi-Mission RTG • The leading hypothesis suggests that the FOD which is causing the internal shorts are extremely small pieces of material that could potentially melt and/or sublimate away given a sufficient amount of current. • By inducing a controlled second short (in the presence of an internal MMRTG chassis short), a significant amount of current flow can be generated to achieve three main design goals: 1) Measure and characterize the MMRTG internal short to chassis, 2) Safely determine if the MMRTG internal short can be cleared in the presence of another controlled short 3) Quantify the amount of energy required to clear the MMRTG internal short. -

Re-Examining the Role of Nuclear Fusion in a Renewables-Based Energy Mix

Re-examining the Role of Nuclear Fusion in a Renewables-Based Energy Mix T. E. G. Nicholasa,∗, T. P. Davisb, F. Federicia, J. E. Lelandc, B. S. Patela, C. Vincentd, S. H. Warda a York Plasma Institute, Department of Physics, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, UK b Department of Materials, University of Oxford, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PH c Department of Electrical Engineering and Electronics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 3GJ, UK d Centre for Advanced Instrumentation, Department of Physics, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LS, UK Abstract Fusion energy is often regarded as a long-term solution to the world's energy needs. However, even after solving the critical research challenges, engineer- ing and materials science will still impose significant constraints on the char- acteristics of a fusion power plant. Meanwhile, the global energy grid must transition to low-carbon sources by 2050 to prevent the worst effects of climate change. We review three factors affecting fusion's future trajectory: (1) the sig- nificant drop in the price of renewable energy, (2) the intermittency of renewable sources and implications for future energy grids, and (3) the recent proposition of intermediate-level nuclear waste as a product of fusion. Within the scenario assumed by our premises, we find that while there remains a clear motivation to develop fusion power plants, this motivation is likely weakened by the time they become available. We also conclude that most current fusion reactor designs do not take these factors into account and, to increase market penetration, fu- sion research should consider relaxed nuclear waste design criteria, raw material availability constraints and load-following designs with pulsed operation. -

Joules Deposition

SURGE RECORDINGS THAT MAKE SENSE Joule Deposition: Yes! – “Joule Content”: Never! Geoffrey Lindes Arshad Mansoor François Martzloff David Vannoy Delmarva Power & Power Electronics National Institute of Delmarva Power & Light Company Applications Center Standards & Technology Light Company Reprinted from Proceedings, PQA’97 USA, 1997 Significance Part 5 – Monitoring instruments, laboratory measurements, and test methods Part 6 – Textbooks and tutorial reviews This paper combines in a single presentation to a forum of electric utilities two earlier papers, one presenting the thesis that the concept of “energy level” of a surge is inappropriate, the other presenting the position that monitoring surge voltages is no longer relevant. 1. The paper offers a rationale for avoiding attempts to characterize the surge environment in low-voltage end-user power systems by a single number – the "energy in the surge" – derived from a simple voltage measurement. Numerical examples illustrate the fallacy of this concept. 2. Furthermore, based on the proliferation of surge-protective devices in low-voltage end-user installations, the paper draws attention to the need for changing focus from surge voltage measurements to surge current measurements. This subject was addressed in several other papers presented on both sides of the Atlantic (See in Part 5 “Keeping up”-1995; “No joules”-1996; Make sense”-1996; “Novel transducer”-2000; and “Galore”-1999 in Part 2), in persistent but unsuccessful attempts to persuade manufacturers and users of power quality monitors, and standards-developing groups concerned with power quality measurements to address the fallacy of continuing to monitor surge voltages in post-1980 power distribution systems As it turned out, the response has been polite interest but no decisive action. -

Fission and Fusion Can Yield Energy

Nuclear Energy Nuclear energy can also be separated into 2 separate forms: nuclear fission and nuclear fusion. Nuclear fusion is the splitting of large atomic nuclei into smaller elements releasing energy, and nuclear fusion is the joining of two small atomic nuclei into a larger element and in the process releasing energy. The mass of a nucleus is always less than the sum of the individual masses of the protons and neutrons which constitute it. The difference is a measure of the nuclear binding energy which holds the nucleus together (Figure 1). As figures 1 and 2 below show, the energy yield from nuclear fusion is much greater than nuclear fission. Figure 1 2 Nuclear binding energy = ∆mc For the alpha particle ∆m= 0.0304 u which gives a binding energy of 28.3 MeV. (Figure from: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/nucene/nucbin.html ) Fission and fusion can yield energy Figure 2 (Figure from: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/nucene/nucbin.html) Nuclear fission When a neutron is fired at a uranium-235 nucleus, the nucleus captures the neutron. It then splits into two lighter elements and throws off two or three new neutrons (the number of ejected neutrons depends on how the U-235 atom happens to split). The two new atoms then emit gamma radiation as they settle into their new states. (John R. Huizenga, "Nuclear fission", in AccessScience@McGraw-Hill, http://proxy.library.upenn.edu:3725) There are three things about this induced fission process that make it especially interesting: 1) The probability of a U-235 atom capturing a neutron as it passes by is fairly high. -

Feeling Joules and Watts

FEELING JOULES AND WATTS OVERVIEW & PURPOSE Power was originally measured in horsepower – literally the number of horses it took to do a particular amount of work. James Watt developed this term in the 18th century to compare the output of steam engines to the power of draft horses. This allowed people who used horses for work on a regular basis to have an intuitive understanding of power. 1 horsepower is about 746 watts. In this lab, you’ll learn about energy, work and power – including your own capacity to do work. Energy is the ability to do work. Without energy, nothing would grow, move, or change. Work is using a force to move something over some distance. work = force x distance Energy and work are measured in joules. One joule equals the work done (or energy used) when a force of one newton moves an object one meter. One newton equals the force required to accelerate one kilogram one meter per second squared. How much energy would it take to lift a can of soda (weighing 4 newtons) up two meters? work = force x distance = 4N x 2m = 8 joules Whether you lift the can of soda quickly or slowly, you are doing 8 joules of work (using 8 joules of energy). It’s often helpful, though, to measure how quickly we are doing work (or using energy). Power is the amount of work (or energy used) in a given amount of time. http://www.rdcep.org/demo-collection page 1 work power = time Power is measured in watts. One watt equals one joule per second. -

Energy and Power Units and Conversions

Energy and Power Units and Conversions Basic Energy Units 1 Joule (J) = Newton meter × 1 calorie (cal)= 4.18 J = energy required to raise the temperature of 1 gram of water by 1◦C 1 Btu = 1055 Joules = 778 ft-lb = 252 calories = energy required to raise the temperature 1 lb of water by 1◦F 1 ft-lb = 1.356 Joules = 0.33 calories 1 physiological calorie = 1000 cal = 1 kilocal = 1 Cal 1 quad = 1015Btu 1 megaJoule (MJ) = 106 Joules = 948 Btu, 1 gigaJoule (GJ) = 109 Joules = 948; 000 Btu 1 electron-Volt (eV) = 1:6 10 19 J × − 1 therm = 100,000 Btu Basic Power Units 1 Watt (W) = 1 Joule/s = 3:41 Btu/hr 1 kiloWatt (kW) = 103 Watt = 3:41 103 Btu/hr × 1 megaWatt (MW) = 106 Watt = 3:41 106 Btu/hr × 1 gigaWatt (GW) = 109 Watt = 3:41 109 Btu/hr × 1 horse-power (hp) = 2545 Btu/hr = 746 Watts Other Energy Units 1 horsepower-hour (hp-hr) = 2:68 106 Joules = 0.746 kwh × 1 watt-hour (Wh) = 3:6 103 sec 1 Joule/sec = 3:6 103 J = 3.413 Btu × × × 1 kilowatt-hour (kWh) = 3:6 106 Joules = 3413 Btu × 1 megaton of TNT = 4:2 1015 J × Energy and Power Values solar constant = 1400W=m2 1 barrel (bbl) crude oil (42 gals) = 5:8 106 Btu = 9:12 109 J × × 1 standard cubic foot natural gas = 1000 Btu 1 gal gasoline = 1:24 105 Btu × 1 Physics 313 OSU 3 April 2001 1 ton coal 3 106Btu ≈ × 1 ton 235U (fissioned) = 70 1012 Btu × 1 million bbl oil/day = 5:8 1012 Btu/day =2:1 1015Btu/yr = 2.1 quad/yr × × 1 million bbl oil/day = 80 million tons of coal/year = 1/5 ton of uranium oxide/year One million Btu approximately equals 90 pounds of coal 125 pounds of dry wood 8 gallons of -

A Review on Thermoelectric Generators: Progress and Applications

energies Review A Review on Thermoelectric Generators: Progress and Applications Mohamed Amine Zoui 1,2 , Saïd Bentouba 2 , John G. Stocholm 3 and Mahmoud Bourouis 4,* 1 Laboratory of Energy, Environment and Information Systems (LEESI), University of Adrar, Adrar 01000, Algeria; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Sustainable Development and Computing (LDDI), University of Adrar, Adrar 01000, Algeria; [email protected] 3 Marvel Thermoelectrics, 11 rue Joachim du Bellay, 78540 Vernouillet, Île de France, France; [email protected] 4 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Av. Països Catalans No. 26, 43007 Tarragona, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 13 July 2020 Abstract: A thermoelectric effect is a physical phenomenon consisting of the direct conversion of heat into electrical energy (Seebeck effect) or inversely from electrical current into heat (Peltier effect) without moving mechanical parts. The low efficiency of thermoelectric devices has limited their applications to certain areas, such as refrigeration, heat recovery, power generation and renewable energy. However, for specific applications like space probes, laboratory equipment and medical applications, where cost and efficiency are not as important as availability, reliability and predictability, thermoelectricity offers noteworthy potential. The challenge of making thermoelectricity a future leader in waste heat recovery and renewable energy is intensified by the integration of nanotechnology. In this review, state-of-the-art thermoelectric generators, applications and recent progress are reported. Fundamental knowledge of the thermoelectric effect, basic laws, and parameters affecting the efficiency of conventional and new thermoelectric materials are discussed. The applications of thermoelectricity are grouped into three main domains. -

The Basic Unit of Energy Is a Joule (J). Other Units Are Kilojoule, Calorie, British Thermal Unit (BTU), and Therm

194 Name ___________________________________ Date ________________ APES Topic 11 – Energy Resources Mr. Romano APES Energy Problems (for this practice, you may use your calculator) The Basics: Energy: The basic unit of energy is a Joule (J). Other units are kilojoule, calorie, British Thermal Unit (BTU), and therm. 1000J = 1 kJ (you should know this already …) Power: Power is the rate at which energy is used. Power (watts) = Energy (joules) time (sec) 1W = 1J/s (1Watt = 1 Joule per second) 1kW = 1000 J/sec 1. A 100 Watt incandescent light bulb uses 100 J/sec of electrical energy. If it is 5% efficient, then the bulb converts 5% of the electrical energy into light and 95% is wasted by being transformed into heat (ever felt a hot light bulb?) a. How is the First Law of Thermodynamics referenced above? b. How is the Second Law of Thermodynamics referenced above? Practice Problems: 2. How much energy, in kJ, does a 75 Watt light bulb use then it is turned on for 25 minutes? 195 3. The Kilowatt Hour, or kWh, is not a unit of power but of energy. Notice that kilowatt is a unit of power and hour is a unit of time. E = P x t (rearranged from above). A kilowatt hour is equal to 1 kW delivered continuously for 1 hour (3600 seconds). a. How many joules are equal to 1 kWh? b. How many kJ are equal to 1 kWh? c. Assume your electric bill showed you used 1355 kWh over a 30-day period. Find the energy used, in kJ, for the 30 day period. -

Work, Power, & Energy

WORK, POWER, & ENERGY In physics, work is done when a force acting on an object causes it to move a distance. There are several good examples of work which can be observed everyday - a person pushing a grocery cart down the aisle of a grocery store, a student lifting a backpack full of books, a baseball player throwing a ball. In each case a force is exerted on an object that caused it to move a distance. Work (Joules) = force (N) x distance (m) or W = f d The metric unit of work is one Newton-meter ( 1 N-m ). This combination of units is given the name JOULE in honor of James Prescott Joule (1818-1889), who performed the first direct measurement of the mechanical equivalent of heat energy. The unit of heat energy, CALORIE, is equivalent to 4.18 joules, or 1 calorie = 4.18 joules Work has nothing to do with the amount of time that this force acts to cause movement. Sometimes, the work is done very quickly and other times the work is done rather slowly. The quantity which has to do with the rate at which a certain amount of work is done is known as the power. The metric unit of power is the WATT. As is implied by the equation for power, a unit of power is equivalent to a unit of work divided by a unit of time. Thus, a watt is equivalent to a joule/second. For historical reasons, the horsepower is occasionally used to describe the power delivered by a machine. -

A) B) C) D) 1. Which Is an SI Unit for Work Done on an Object? A) Kg•M/S

1. Which is an SI unit for work done on an object? 10. Which is an acceptable unit for impulse? A) B) A) N•m B) J/s C) J•s D) kg•m/s C) D) 11. Using dimensional analysis, show that the expression has the same units as acceleration. [Show all the 2. Which combination of fundamental units can be used to express energy? steps used to arrive at your answer.] A) kg•m/s B) kg•m2/s 12. Which quantity and unit are correctly paired? 2 2 2 C) kg•m/s D) kg•m /s A) 3. A joule is equivalent to a B) A) N•m B) N•s C) N/m D) N/s C) 4. A force of 1 newton is equivalent to 1 A) B) D) C) D) 13. Which two quantities are measured in the same units? 5. Which two quantities can be expressed using the same A) mechanical energy and heat units? B) energy and power A) energy and force C) momentum and work B) impulse and force D) work and power C) momentum and energy 14. Which is a derived unit? D) impulse and momentum A) meter B) second 6. Which pair of quantities can be expressed using the same C) kilogram D) Newton units? 15. Which combination of fundamental unit can be used to A) work and kinetic energy express the weight of an object? B) power and momentum A) kilogram/second C) impulse and potential energy B) kilogram•meter D) acceleration and weight C) kilogram•meter/second 7.