Joule Equivalent of Electrical Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printer Tech Tips—Cause & Effects of Static Electricity in Paper

Printer Tech Tips Cause & Effects of Static Electricity in Paper Problem The paper has developed a static electrical charge causing an abnormal sheet-to- sheet or sheet-to-material attraction which is difficult to separate. This condition may result in feeder trip-offs, print voids from surface contamination, ink offset, Sappi Printer Technical Service or poor sheet jog in the delivery. 877 SappiHelp (727 7443) Description Static electricity is defined as a non-moving, non-flowing electrical charge or in simple terms, electricity at rest. Static electricity becomes visible and dynamic during the brief moment it sparks a discharge and for that instant it’s no longer at rest. Lightning is the result of static discharge as is the shock you receive just before contacting a grounded object during unusually dry weather. Matter is composed of atoms, which in turn are composed of protons, neutrons, and electrons. The number of protons and neutrons, which make up the atoms nucleus, determine the type of material. Electrons orbit the nucleus and balance the electrical charge of the protons. When both negative and positive are equal, the charge of the balanced atom is neutral. If electrons are removed or added to this configuration, the overall charge becomes either negative or positive resulting in an unbalanced atom. Materials with high conductivity, such as steel, are called conductors and maintain neutrality because their electrons can move freely from atom to atom to balance any applied charges. Therefore, conductors can dissipate static when properly grounded. Non-conductive materials, or insulators such as plastic and wood, have the opposite property as their electrons can not move freely to maintain balance. -

A Review of Energy Storage Technologies' Application

sustainability Review A Review of Energy Storage Technologies’ Application Potentials in Renewable Energy Sources Grid Integration Henok Ayele Behabtu 1,2,* , Maarten Messagie 1, Thierry Coosemans 1, Maitane Berecibar 1, Kinde Anlay Fante 2 , Abraham Alem Kebede 1,2 and Joeri Van Mierlo 1 1 Mobility, Logistics, and Automotive Technology Research Centre, Vrije Universiteit Brussels, Pleinlaan 2, 1050 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (T.C.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (A.A.K.); [email protected] (J.V.M.) 2 Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Jimma Institute of Technology, Jimma University, Jimma P.O. Box 378, Ethiopia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-485659951 or +251-926434658 Received: 12 November 2020; Accepted: 11 December 2020; Published: 15 December 2020 Abstract: Renewable energy sources (RESs) such as wind and solar are frequently hit by fluctuations due to, for example, insufficient wind or sunshine. Energy storage technologies (ESTs) mitigate the problem by storing excess energy generated and then making it accessible on demand. While there are various EST studies, the literature remains isolated and dated. The comparison of the characteristics of ESTs and their potential applications is also short. This paper fills this gap. Using selected criteria, it identifies key ESTs and provides an updated review of the literature on ESTs and their application potential to the renewable energy sector. The critical review shows a high potential application for Li-ion batteries and most fit to mitigate the fluctuation of RESs in utility grid integration sector. -

AST242 LECTURE NOTES PART 3 Contents 1. Viscous Flows 2 1.1. the Velocity Gradient Tensor 2 1.2. Viscous Stress Tensor 3 1.3. Na

AST242 LECTURE NOTES PART 3 Contents 1. Viscous flows 2 1.1. The velocity gradient tensor 2 1.2. Viscous stress tensor 3 1.3. Navier Stokes equation { diffusion 5 1.4. Viscosity to order of magnitude 6 1.5. Example using the viscous stress tensor: The force on a moving plate 6 1.6. Example using the Navier Stokes equation { Poiseuille flow or Flow in a capillary 7 1.7. Viscous Energy Dissipation 8 2. The Accretion disk 10 2.1. Accretion to order of magnitude 14 2.2. Hydrostatic equilibrium for an accretion disk 15 2.3. Shakura and Sunyaev's α-disk 17 2.4. Reynolds Number 17 2.5. Circumstellar disk heated by stellar radiation 18 2.6. Viscous Energy Dissipation 20 2.7. Accretion Luminosity 21 3. Vorticity and Rotation 24 3.1. Helmholtz Equation 25 3.2. Rate of Change of a vector element that is moving with the fluid 26 3.3. Kelvin Circulation Theorem 28 3.4. Vortex lines and vortex tubes 30 3.5. Vortex stretching and angular momentum 32 3.6. Bernoulli's constant in a wake 33 3.7. Diffusion of vorticity 34 3.8. Potential Flow and d'Alembert's paradox 34 3.9. Burger's vortex 36 4. Rotating Flows 38 4.1. Coriolis Force 38 4.2. Rossby and Ekman numbers 39 4.3. Geostrophic flows and the Taylor Proudman theorem 39 4.4. Two dimensional flows on the surface of a planet 41 1 2 AST242 LECTURE NOTES PART 3 4.5. Thermal winds? 42 5. -

Energy Literacy Essential Principles and Fundamental Concepts for Energy Education

Energy Literacy Essential Principles and Fundamental Concepts for Energy Education A Framework for Energy Education for Learners of All Ages About This Guide Energy Literacy: Essential Principles and Intended use of this document as a guide includes, Fundamental Concepts for Energy Education but is not limited to, formal and informal energy presents energy concepts that, if understood and education, standards development, curriculum applied, will help individuals and communities design, assessment development, make informed energy decisions. and educator trainings. Energy is an inherently interdisciplinary topic. Development of this guide began at a workshop Concepts fundamental to understanding energy sponsored by the Department of Energy (DOE) arise in nearly all, if not all, academic disciplines. and the American Association for the Advancement This guide is intended to be used across of Science (AAAS) in the fall of 2010. Multiple disciplines. Both an integrated and systems-based federal agencies, non-governmental organizations, approach to understanding energy are strongly and numerous individuals contributed to the encouraged. development through an extensive review and comment process. Discussion and information Energy Literacy: Essential Principles and gathered at AAAS, WestEd, and DOE-sponsored Fundamental Concepts for Energy Education Energy Literacy workshops in the spring of 2011 identifies seven Essential Principles and a set of contributed substantially to the refinement of Fundamental Concepts to support each principle. the guide. This guide does not seek to identify all areas of energy understanding, but rather to focus on those To download this guide and related documents, that are essential for all citizens. The Fundamental visit www.globalchange.gov. Concepts have been drawn, in part, from existing education standards and benchmarks. -

3.Joule's Experiments

The Force of Gravity Creates Energy: The “Work” of James Prescott Joule http://www.bookrags.com/biography/james-prescott-joule-wsd/ James Prescott Joule (1818-1889) was the son of a successful British brewer. He tinkered with the tools of his father’s trade (particularly thermometers), and despite never earning an undergraduate degree, he was able to answer two rather simple questions: 1. Why is the temperature of the water at the bottom of a waterfall higher than the temperature at the top? 2. Why does an electrical current flowing through a conductor raise the temperature of water? In order to adequately investigate these questions on our own, we need to first define “temperature” and “energy.” Second, we should determine how the measurement of temperature can relate to “heat” (as energy). Third, we need to find relationships that might exist between temperature and “mechanical” energy and also between temperature and “electrical” energy. Definitions: Before continuing, please write down what you know about temperature and energy below. If you require more space, use the back. Temperature: Energy: We have used the concept of gravity to show how acceleration of freely falling objects is related mathematically to distance, time, and speed. We have also used the relationship between net force applied through a distance to define “work” in the Harvard Step Test. Now, through the work of Joule, we can equate the concepts of “work” and “energy”: Energy is the capacity of a physical system to do work. Potential energy is “stored” energy, kinetic energy is “moving” energy. One type of potential energy is that induced by the gravitational force between two objects held at a distance (there are other types of potential energy, including electrical, magnetic, chemical, nuclear, etc). -

Toolkit 1: Energy Units and Fundamentals of Quantitative Analysis

Energy & Society Energy Units and Fundamentals Toolkit 1: Energy Units and Fundamentals of Quantitative Analysis 1 Energy & Society Energy Units and Fundamentals Table of Contents 1. Key Concepts: Force, Work, Energy & Power 3 2. Orders of Magnitude & Scientific Notation 6 2.1. Orders of Magnitude 6 2.2. Scientific Notation 7 2.3. Rules for Calculations 7 2.3.1. Multiplication 8 2.3.2. Division 8 2.3.3. Exponentiation 8 2.3.4. Square Root 8 2.3.5. Addition & Subtraction 9 3. Linear versus Exponential Growth 10 3.1. Linear Growth 10 3.2. Exponential Growth 11 4. Uncertainty & Significant Figures 14 4.1. Uncertainty 14 4.2. Significant Figures 15 4.3. Exact Numbers 15 4.4. Identifying Significant Figures 16 4.5. Rules for Calculations 17 4.5.1. Addition & Subtraction 17 4.5.2. Multiplication, Division & Exponentiation 18 5. Unit Analysis 19 5.1. Commonly Used Energy & Non-energy Units 20 5.2. Form & Function 21 6. Sample Problems 22 6.1. Scientific Notation 22 6.2. Linear & Exponential Growth 22 6.3. Significant Figures 23 6.4. Unit Conversions 23 7. Answers to Sample Problems 24 7.1. Scientific Notation 24 7.2. Linear & Exponential Growth 24 7.3. Significant Figures 24 7.4. Unit Conversions 26 8. References 27 2 Energy & Society Energy Units and Fundamentals 1. KEY CONCEPTS: FORCE, WORK, ENERGY & POWER Among the most important fundamentals to be mastered when studying energy pertain to the differences and inter-relationships among four concepts: force, work, energy, and power. Each of these terms has a technical meaning in addition to popular or colloquial meanings. -

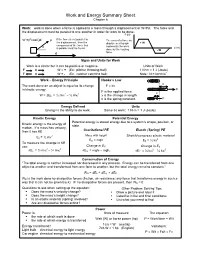

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Active Short Circuit - Chassis Short Characterization and Potential Mitigation Technique for the MMRTG

Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Multi-Mission RTG Active Short Circuit - Chassis Short Characterization and Potential Mitigation Technique for the MMRTG February 25, 2015 Gary Bolotin1 Nicholas Keyawa1 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology 1 Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Agenda Multi-Mission RTG • Introduction – MMRTG – Internal MMRTG Chassis Shorts • Active Short Circuit Purpose • Active Short Circuit Theory • Active Short Design and Component Layout • Conclusion and Future Work 2 Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Introduction – MMRTG Multi-Mission RTG • The Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG) utilizes a combination of PbTe, PbSnTe, and TAGS thermoelectric couples to produce electric current from the heat generated by the radioactive decay of plutonium – 238. 3 Jet Propulsion Laboratory Introduction – Internal MMRTG Chassis California Institute of Technology Shorts Multi-Mission RTG • Shorts inside the MMRTG between the electrical power circuit and the MMRTG chassis have been detected via isolation checks and/or changes in the bus balance voltage. • Example location of short shown below MMRTG Chassis Internal MMRTG Short 4 Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Active Short Circuit Purpose Multi-Mission RTG • The leading hypothesis suggests that the FOD which is causing the internal shorts are extremely small pieces of material that could potentially melt and/or sublimate away given a sufficient amount of current. • By inducing a controlled second short (in the presence of an internal MMRTG chassis short), a significant amount of current flow can be generated to achieve three main design goals: 1) Measure and characterize the MMRTG internal short to chassis, 2) Safely determine if the MMRTG internal short can be cleared in the presence of another controlled short 3) Quantify the amount of energy required to clear the MMRTG internal short. -

Re-Examining the Role of Nuclear Fusion in a Renewables-Based Energy Mix

Re-examining the Role of Nuclear Fusion in a Renewables-Based Energy Mix T. E. G. Nicholasa,∗, T. P. Davisb, F. Federicia, J. E. Lelandc, B. S. Patela, C. Vincentd, S. H. Warda a York Plasma Institute, Department of Physics, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, UK b Department of Materials, University of Oxford, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PH c Department of Electrical Engineering and Electronics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 3GJ, UK d Centre for Advanced Instrumentation, Department of Physics, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LS, UK Abstract Fusion energy is often regarded as a long-term solution to the world's energy needs. However, even after solving the critical research challenges, engineer- ing and materials science will still impose significant constraints on the char- acteristics of a fusion power plant. Meanwhile, the global energy grid must transition to low-carbon sources by 2050 to prevent the worst effects of climate change. We review three factors affecting fusion's future trajectory: (1) the sig- nificant drop in the price of renewable energy, (2) the intermittency of renewable sources and implications for future energy grids, and (3) the recent proposition of intermediate-level nuclear waste as a product of fusion. Within the scenario assumed by our premises, we find that while there remains a clear motivation to develop fusion power plants, this motivation is likely weakened by the time they become available. We also conclude that most current fusion reactor designs do not take these factors into account and, to increase market penetration, fu- sion research should consider relaxed nuclear waste design criteria, raw material availability constraints and load-following designs with pulsed operation. -

Energy and the Hydrogen Economy

Energy and the Hydrogen Economy Ulf Bossel Fuel Cell Consultant Morgenacherstrasse 2F CH-5452 Oberrohrdorf / Switzerland +41-56-496-7292 and Baldur Eliasson ABB Switzerland Ltd. Corporate Research CH-5405 Baden-Dättwil / Switzerland Abstract Between production and use any commercial product is subject to the following processes: packaging, transportation, storage and transfer. The same is true for hydrogen in a “Hydrogen Economy”. Hydrogen has to be packaged by compression or liquefaction, it has to be transported by surface vehicles or pipelines, it has to be stored and transferred. Generated by electrolysis or chemistry, the fuel gas has to go through theses market procedures before it can be used by the customer, even if it is produced locally at filling stations. As there are no environmental or energetic advantages in producing hydrogen from natural gas or other hydrocarbons, we do not consider this option, although hydrogen can be chemically synthesized at relative low cost. In the past, hydrogen production and hydrogen use have been addressed by many, assuming that hydrogen gas is just another gaseous energy carrier and that it can be handled much like natural gas in today’s energy economy. With this study we present an analysis of the energy required to operate a pure hydrogen economy. High-grade electricity from renewable or nuclear sources is needed not only to generate hydrogen, but also for all other essential steps of a hydrogen economy. But because of the molecular structure of hydrogen, a hydrogen infrastructure is much more energy-intensive than a natural gas economy. In this study, the energy consumed by each stage is related to the energy content (higher heating value HHV) of the delivered hydrogen itself. -

NASA Radioisotope Power Conversion Technology NRA Overview

NASA Radioisotope Power Conversion Technology NRA Overview David J. Anderson NASA Glenn Research Center, 21000 Brookpark Road, Cleveland, OH 44135 216-433-8709, [email protected] Abstract. The focus of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Radioisotope Power Systems (RPS) Development program is aimed at developing nuclear power and technologies that would improve the effectiveness of space science missions. The Radioisotope Power Conversion Technology (RPCT) NASA Research Announcement (NRA) is an important mechanism through which research and technology activities are supported in the Advanced Power Conversion Research and Technology project of the Advanced Radioisotope Power Systems Development program. The purpose of the RPCT NRA is to advance the development of radioisotope power conversion technologies to provide higher efficiencies and specific powers than existing systems. These advances would enable a factor of 2 to 4 decrease in the amount of fuel and a reduction of waste heat required to generate electrical power, and thus could result in more cost effective science missions for NASA. The RPCT NRA selected advanced RPS power conversion technology research and development proposals in the following three areas: innovative RPS power conversion research, RPS power conversion technology development in a nominal 100We scale; and, milliwatt/multi-watt RPS (mWRPS) power conversion research. Ten RPCT NRA contracts were awarded in 2003 in the areas of Brayton, Stirling, thermoelectric (TE), and thermophotovoltaic (TPV) power conversion technologies. This paper will provide an overview of the RPCT NRA, a summary of the power conversion technologies approaches being pursued, and a brief digest of first year accomplishments. RADIOISOTOPE POWER CONVERSION TECHNOLOGY (RPCT) OVERVIEW The objective of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Radioisotope Power Systems (RPS) Development program is to develop nuclear power conversion technologies that would improve the effectiveness of space science missions. -

Electricity Production by Fuel

EN27 Electricity production by fuel Key message Fossil fuels and nuclear energy continue to dominate the fuel mix for electricity production despite their risk of environmental impact. This impact was reduced during the 1990s with relatively clean natural gas becoming the main choice of fuel for new plants, at the expense of oil, in particular. Production from coal and lignite has increased slightly in recent years but its share of electricity produced has been constant since 2000 as overall production increases. The steep increase in overall electricity production has also counteracted some of the environmental benefits from fuel switching. Rationale The trend in electricity production by fuel provides a broad indication of the impacts associated with electricity production. The type and extent of the related environmental pressures depends upon the type and amount of fuels used for electricity generation as well as the use of abatement technologies. Fig. 1: Gross electricity production by fuel, EU-25 5,000 4,500 4,000 Other fuels 3,500 Renewables 1.4% 3,000 13.7% Nuclear 2,500 TWh Natural and derived 31.0% gas 2,000 Coal and lignite 1,500 19.9% Oil 1,000 29.5% 500 4.5% 0 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2010 2020 2030 Data Source: Eurostat (Historic data), Primes Energy Model (European Commission 2006) for projections. Note: Data shown are for gross electricity production and include electricity production from both public and auto-producers. Renewables includes electricity produced from hydro (excluding pumping), biomass, municipal waste, geothermal, wind and solar PV.