S/2003/669 Security Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TERRORIST TRIALS: a Report Card

A P U B L I C A T I O N O F T H E C E N T E R O N L A W A N D S E C U R I T Y A T N Y U S C H O O L O F L A W | F E B R U A R Y 2 0 0 5 110 W E S T T H I R D S T R E E T , N E W Y O R K , N Y 10 0 12 | W W W . L A W . N Y U . E D U / C E N T E R S / L A W S E C U R I T Y TERRORIST TRIALS: A Report Card hen he announced his resignation in November 2004, Attorney General John Ashcroft declared, “The objective of securing the safety of Americans W from crime and terror has been achieved.” He was referring to that part of the war for which he was largely respo n s i b l e : the legal and judicial record. Ei g h t e e n months prior to that, in testimony before Congress, Ashcroft summed up the pretrial, interim results of his war on terror. Ashcroft cited 18,000 subpoenas, 211 criminal charges, 47 8 [As a preliminary note to the findings, it is important to point deportations and $124 million in frozen assets. Looking to out that accurate and comprehensive information was almost document the results of these efforts, represented in the prose- impossible to obtain. -

30 Terrorist Plots Foiled: How the System Worked Jena Baker Mcneill, James Jay Carafano, Ph.D., and Jessica Zuckerman

No. 2405 April 29, 2010 30 Terrorist Plots Foiled: How the System Worked Jena Baker McNeill, James Jay Carafano, Ph.D., and Jessica Zuckerman Abstract: In 2009 alone, U.S. authorities foiled at least six terrorist plots against the United States. Since Septem- ber 11, 2001, at least 30 planned terrorist attacks have Talking Points been foiled, all but two of them prevented by law enforce- • At least 30 terrorist plots against the United ment. The two notable exceptions are the passengers and States have been foiled since 9/11. It is clear flight attendants who subdued the “shoe bomber” in 2001 that terrorists continue to wage war against and the “underwear bomber” on Christmas Day in 2009. America. Bottom line: The system has generally worked well. But • President Obama spent his first year and a half many tools necessary for ferreting out conspiracies and in office dismantling many of the counterter- catching terrorists are under attack. Chief among them are rorism tools that have kept Americans safer, key provisions of the PATRIOT Act that are set to expire at including his decision to prosecute foreign ter- the end of this year. It is time for President Obama to dem- rorists in U.S. civilian courts, dismantlement of onstrate his commitment to keeping the country safe. Her- the CIA’s interrogation abilities, lackadaisical itage Foundation national security experts provide a road support for the PATRIOT Act, and an attempt map for a successful counterterrorism strategy. to shut down Guantanamo Bay. • The counterterrorism system that has worked successfully in the past must be pre- served in order for the nation to be successful In 2009, at least six planned terrorist plots against in fighting terrorists in the future. -

Homeland Security Implications of Radicalization

THE HOMELAND SECURITY IMPLICATIONS OF RADICALIZATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 20, 2006 Serial No. 109–104 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35–626 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman DON YOUNG, Alaska BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas LORETTA SANCHEZ, California CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut NORMAN D. DICKS, Washington JOHN LINDER, Georgia JANE HARMAN, California MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon TOM DAVIS, Virginia NITA M. LOWEY, New York DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM GIBBONS, Nevada Columbia ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut ZOE LOFGREN, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON-LEE, Texas STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey KATHERINE HARRIS, Florida DONNA M. CHRISTENSEN, U.S. Virgin Islands BOBBY JINDAL, Louisiana BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina DAVE G. REICHERT, Washington JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MICHAEL MCCAUL, Texas KENDRICK B. MEEK, Florida CHARLIE DENT, Pennsylvania GINNY BROWN-WAITE, Florida SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut, Chairman CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania ZOE LOFGREN, California MARK E. -

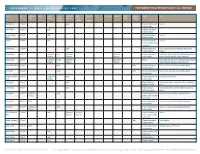

Terrorist Trial Report Card: U.S. Edition – Appendix B

SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 – SEPTEMBER 11, 2006 TERRORIST TRIAL REPORT CARD: U.S. EDITION Name Date Commercial Drugs General General Immigration National Obstruction Other Racketeering Terrorism Violent Weapons Sentence Notes Fraud Fraud Criminal Violations Security of Crimes Violations Conspiracy Violations Investigation Khalid Al Draibi 12-Sep-01 Guilty 4 months imprisonment, 36 Deported months probation Sherif Khamis 13-Sep-01 Guilty 2.5 months imprisonment, 36 months probation Jean-Tony Antoine 14-Sep-01 Guilty 12 months imprisonment, Deported Oulai 24 months probation Atif Raza 17-Sep-01 Guilty 4.7 months imprisonment, Deported 36 months probation, $4,183 fine/restitution Francis Guagni 17-Sep-01 Guilty 20 months imprisonment, French national arrested at Canadian border with box cutter; 36 months probation Deported Ahmed Hannan 18-Sep-01 Acquitted or Guilty Acquitted or Acquitted or 6 months imprisonment, 24 Detroit Sleeper Cell Case (Karim Koubriti, Ahmed Hannan, Youssef Dismissed Dismissed Dismissed months probation Hmimssa, Abdel Ilah Elmardoudi, Farouk Ali-Haimoud) Karim Koubriti 18-Sep-01 Acquitted or Pending Acquitted or Acquitted or Pending Detroit Sleeper Cell Case (Karim Koubriti, Ahmed Hannan, Youssef Dismissed Dismissed Dismissed Hmimssa, Abdel Ilah Elmardoudi, Farouk Ali-Haimoud) Vincente Rafael Pierre 18-Sep-01 Guilty Guilty 24 months imprisonment, Pierre et al. (Vincente Rafael Pierre, Traci Elaine Upshur) 36 months probation Traci Upshur 18-Sep-01 Guilty Guilty 15 months imprisonment, 24 Pierre et al. (Vincente Rafael Pierre, -

Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans Author: David Schanzer, Charles Kurzman, Ebrahim Moosa Document No.: 229868 Date Received: March 2010 Award Number: 2007-IJ-CX-0008 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Anti- Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans DAVID SCHANZER SANFORD SCHOOL OF PUBLIC POLICY DUKE UNIVERSITY CHARLES KURZMAN DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL EBRAHIM MOOSA DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION DUKE UNIVERSITY JANUARY 6, 2010 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Project Supported by the National Institute of Justice This project was supported by grant no. -

R M Irsu Iftftactkt

Page 2 Sept. 18 - 24, 2002 mi ii ■ r = In the news this week: Community Crime Log Train derailment UA student A D INDEX running for KEN SWEET a young,female in a gray up hk sleeve. He then tried to spills sulfuric acid Absolute Bikes 14 wallc out of the store but was T he L u m b e r ja c k sweater walked into the store onto countryside and asked the clerk if they had stopped by store personnel. Army National When the police arrived, Running under the slogan, Sept. 16 arky cameras. The clerk said A train in West Knoxville, Gearhart told police he had the “What’s the worst I could do," yes, and the girl picked up the Tcnn. derailed spilling approx money for the alcohol, but was University of Arizona senior Guard 14 12 pack of soda and told the innately 300*000 gallons of sul • Julian Gonzales a 19 year clerk, she was going to take unable to buy it because he history major, Carlton furic acid into Fort Loudon Rahmani, is an overlooked old Flagstaff resident was this." The girl walked out of was underage. Gearhart was AT&T 8 arrested and charged with arrested and booked into Lake. write-in for governor. the store with the soda. No Officials ordered a 1.3-mile assault. During the afternoon, suspects have been found. Coconino County jail. ’ N Running as a Republican the victim joe Valencia was- radius evacuation, and for any one of Rahmani’s propositions AZ School of one in a 3 mile radius not to driving along 6th Avenue •Leo Martinez, a 20-year old includes “A Beer-or a Brain’ tax use their air conditioners. -

Pistole Statement

Statement of John S. Pistole Executive Assistant Director for Counterterrorism/Counterintelligence Federal Bureau of Investigation before the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States April 14, 2004 Chairman Kean, Vice Chairman Hamilton, and members of the Commission, thank you for this opportunity to appear before you and the American people today to discuss the FBI’s Counterterrorism mission. I am honored today to speak to you on behalf of the dedicated men and women of the FBI who are working around the clock and all over the globe to combat terrorism. The FBI remains committed to fighting the threats posed by terrorism. But by no means do we fight this battle alone. I want to take a moment to thank our law enforcement and Intelligence Community partners, both domestic and international, for their invaluable assistance and support. I also thank this Commission. The FBI appreciates your tremendous efforts to make recommendations that will help the FBI evolve to meet and defeat terrorist threats. We will continue to work closely with you and your staff to provide access to FBI personnel and information, for the purpose of ultimately strengthening the security of our Nation. To the victims and family members that suffer as a result of the horrific attacks of September 11, 2001--and all acts of terrorism--the FBI has been heartened by your gratitude and mindful of your criticism. Under Director Mueller's leadership, the FBI has not merely begun a process of considered review--it has engaged in an unprecedented transformation. Today, the FBI is better positioned to fulfill its highest priority: “to Protect the United States from Terrorist attack.” The FBI employs a multifaceted approach in order to accomplish its mission. -

A Models Details B More Analyses

A Models Details parameters. When we train and evaluate the model on the dataset, the document is truncated to the S-Reader The model architecture of S-Reader is maximum length of min(2000; max(1000;L )) divided into the encoder module and the decoder th words, where L is the length which covers 90% module. The encoder module is identical to that th of documents in the whole examples. of our sentence selector. It first takes the docu- ment and the question as inputs, obtains document Selection details Here, we describe how to dy- L ×h embeddings D 2 R d d , question embeddings namically select sentences using Dyn method. Lq×hd Q 2 R and question-aware document em- Given the sentences Sall = fs1; s2; s3; :::; sng, or- q L ×h q beddings D 2 R d d , where D is defined as dered by scores from the sentence selector in de- Equation1, and finally obtains document encod- scending order, the selected sentences Sselected is ings Denc and question encodings Qenc as Equa- as follows. tion3. The decoder module obtains the scores for start and end position of the answer span by calcu- Scandidate = fsi 2 Salljscore(si) >= 1 −(14)thg lating bilinear similarities between document en- ( Scandidate ifScandidate = ; codings and question encodings as follows. Sselected = (15) fs1g o:w: T enc Lq β = softmax(w1 Q ) 2 R (10) Here, score(s ) is the score of sentence s from Lq i i enc~ X enc h the sentence selector, and th is a hyperparameter q = (βjQj ) 2 R (11) 0 1 j=1 between and . -

When Jihadis Come Marching Home: the Terrorist Threat Posed by Westerners Returning from Syria and Iraq

Perspective C O R P O R A T I O N Expert insights on a timely policy issue When Jihadis Come Marching Home The Terrorist Threat Posed by Westerners Returning from Syria and Iraq Brian Michael Jenkins lthough the numbers of Western fighters slipping off to total number. U.S. intelligence sources indicate that 100 or more join the jihadist fronts in Syria and Iraq are murky, U.S. Americans have been identified. In an interview on October 5, counterterrorism officials believe that those fighters pose 2014, Federal Bureau of Investigation Director James Comey said a clear and present danger to American security. Some that the FBI knew the identities of “a dozen or so” Americans who Awill be killed in the fighting, some will choose to remain in the were fighting in Syria on the side of the terrorists (Comey, 2014). Middle East, but some will return, more radicalized, determined to His comment surprised many who were familiar with the intel- continue their violent campaigns at home. Their presence in Syria ligence reports, but he was probably referring to a narrowly defined and Iraq also increases the available reservoir of Western passports category of persons who at the time of his statement were known and “clean skins” that terrorist planners could recruit to carry out to be currently fighting with particular terrorist groups in Syria. If terrorist missions against the West. we include all of those who went to or tried to go to Syria or Iraq How many Americans have gone to Syria? It is estimated to join various rebel formations, some of whom were arrested upon that as many as 15,000 foreigners have gone to Syria and Iraq to departure, some of whom were killed in the fighting, and some of fight against the Syrian or Iraqi governments, including more than whom have returned, the larger number would apply. -

Congressional Research Service

Order No. EBTER125 July 1, 2004 Congressional Research Service Terrorism : Federal Crimes Implicated Charles Doyle Issue Definition Current Law Convictions and Current_ Charges Terrorist Cells Providing Financial Support Enemy Combatants GuantanamoCharges Assistance to Countries Supporting Terrorism Issue Definition The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, implicated a number of federal criminal laws . Although the hijackers themselves died in the attacks, federal prosecutors have filed charges in several terrorist-related cases . Zacarias Moussaoui is being prosecuted as a co-conspirator of the hijackers . Three other men, alleged to have helped them secure false identification, have entered plea bargains. In terrorist cases not directly linked to the September 11 attacks, Richard Reid, has been sentenced to life imprisonment for trying to destroy an international flight using explosives concealed in his shoes . John Walker Lindh, the so-called American Taliban, pled guilty to lesser charges after being indicted for conspiring to murder an American overseas and for providing material support to Al Qaeda and the Taliban . Two others, American Jose Padilla and Qatari Ali Saleh Kahlah Al-Marri, initially accused of criminal offenses have been declared enemy combatants and turned over to military authorities . Two nationals of Yemen have been indicted, but remain at large, for the attacks on the USS Cole and the USS The Sullivans in Aden, Yeman . Civilian and military authorities have also brought charges involving the mishandling of classified information relating to the incarceration of enemy combatants in Guantanamo, Cuba . Elsewhere, an attorney for the Sheikh Abdel Rahman convicted of sedition for earlier acts of terrorism, has been accused of a series of crimes relating to Rahman's continued involvement with terrorist activities . -

U.S. Thwarts 19 Terrorist Attacks Against America Since 9/11 James Jay Carafano, Ph.D

No. 2085 November 13, 2007 U.S. Thwarts 19 Terrorist Attacks Against America Since 9/11 James Jay Carafano, Ph.D. Criticisms of post-9/11 efforts to protect the United States from attack range from claims that America is more vulnerable than ever to the contention that the Talking Points transnational terrorist danger is vastly over-hyped.1 A review of publicly available information on at least 19 • A number of plots conducted by individuals have been prevented as a result of the in- terrorist conspiracies thwarted by U.S. law enforce- crease in effective counterterrorism investi- ment suggests that the truth lies somewhere in gations by the United States in cooperation between these two arguments. with friendly and allied governments. U.S. agencies are actively combating individuals and • The list of publicly known arrests demon- groups that are intent on killing Americans and plot- strates conclusively that the lack of another ting mayhem to foster violent extremist political and major terrorist attack is not a sign that organi- religious agendas. A review of the data suggests several zations have relinquished their essential goals. important conclusions: • Future efforts to mitigate the threat of tran- • Combating terrorism is essential for keeping Amer- snational terrorism should follow the exam- ica safe, free, and prosperous. ple set by post-9/11 operations by respecting both the rule of law and liberties guaranteed • Counterterrorism operations have uncovered threats by the Constitution and the necessity of con- that in some cases, although less sophisticated than ducting concerted efforts to seek out and the 9/11 attacks and at most loosely affiliated with frustrate terrorist conspiracies before they “al-Qaeda” central, could have resulted in signifi- come to fruition. -

DAYID COHEN - Vefgus - 71Civ.2203 (CSH) SPBCIAL SERVICES DIVISION, Alvabureau of Speoial Services; WILLIAM H.T

I.INITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ----------------x BARBARA HANDSCHU, RALPH DiGIA, ALEX MCKEIVER, SHABA OM, CURTIS M. POWELL, ABBIE HOFFMAN, MARK A. SAGAL, MICHAEL ZUMOFF, KENNETH THOMAS, ROBERT RUSCH, A}INETTE T. RUBINSTEIN, MICKEY SHEzuD,{}], JOE SUCHER, STEVEN FISCHLER, HOWARD BLATT' ELLIE BBNZONI, on bshalf of themselves and all others similarly situated, Plaintiffs, DECLARATION OF DAYID COHEN - vefgus - 71Civ.2203 (CSH) SPBCIAL SERVICES DIVISION, alVaBureau of Speoial Services; WILLIAM H.T. SMITH; ARTHUR GRUBERT; MICHAEL'WILLIS; WLLIAM KNAPP; PATRICK MURPHY; POLICE DEPARTMENT OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK; JOHN V, LINDSAY; and various unknown employees of the Police Deparhnent acting as undercover operators and informers, Defsndants. x DAVID COHEN, declares under penalty of perjury and pursuantlo 28 U.S.C. $174ó that the following staternents are true and correct: L I am Deputy Commissioner for Intelligence for the New York Cíty Police Department (,,NyPD',), This declaration is based upon personal knowledgo, books and records of the NypD, and upon infbrmation received from employees of the NYPD which I believe to bo true, Z. In my capacity as Deputy Commissioner for Intelligence, I have general oversight of the Intolligence Division, the unit within the N\?D that gathers and analyzes information to assist in the dotection and prevention of unlawful aotivity, including aots of tenor. As such, I have fusthand knowledge of the faots set forth below, I submit this declaration in support of Defendants' Opposition to