No. 159 John H. Gill, 1809 Thunder on the Danub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Napoleon Series

The Napoleon Series The Germans under the French Eagles: Volume II The Baden Contingent – Chapter 3 Part I By Commandant Sauzey Translated by Greg Gorsuch CHAPTER III CAMPAIGN OF 1809 EBERBERG. -- ESSLING. -- RAAB. -- WAGRAM. -- HOLLABRUNN. ZNAÏN. _____________________ Austria, seeing the Emperor engaged in the Spanish war and desiring to take revenge for Austerlitz, was arming silently and preparing to enter the field. As early as October 1808, the Grand Duke of Baden had warned Napoleon of Austrian arming and he had replied on 17 October, reassuring his ally and assuring him that he could not see between Austria and France any reason for a rupture. But at the beginning of 1809, there were no more illusions possible: a conflict became imminent and it was necessary, without delay, to cover all eventualities.1 The Emperor Napoleon to Grand Duke Charles Frederick of Baden. Valladolid, 15 January 1809. "My brother, having beaten and destroyed the Spanish armies and defeated the English army, and learning that Austria is continuing her arming and making movements, I have thought fit to go to Paris. I pray your Royal Highness to inform me immediately of the situation of his troops. I was satisfied with the ones he sent me for Spain. I hope that your Highness will be able to supplement with 8,000 men the troops whom he will put in campaign, because it is better to bring war to our enemies than to receive it." "With that, I pray to God that he will have you in his holy and worthy guard." Your good brother, NAPOLEON. -

The Command and Control of the Grand Armee Napoleon As Organizational Designer

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2009-06 The command and control of the Grand Armee Napoleon as organizational designer Durham, Norman L. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/4722 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS THE COMMAND AND CONTROL OF THE GRAND ARMEE: NAPOLEON AS ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGNER by Norman L. Durham June 2009 Thesis Advisor: Karl D. Pfeiffer Second Reader: Steven J. Iatrou Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2009 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE The Command and Control of the Grand Armee: 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Napoleon as Organizational Designer 6. AUTHOR(S) Norman L. Durham 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

Waterloo in Myth and Memory: the Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Waterloo in Myth and Memory: The Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WATERLOO IN MYTH AND MEMORY: THE BATTLES OF WATERLOO 1815-1915 By TIMOTHY FITZPATRICK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Timothy Fitzpatrick defended this dissertation on November 6, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Dissertation Amiée Boutin University Representative James P. Jones Committee Member Michael Creswell Committee Member Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my Family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Drs. Rafe Blaufarb, Aimée Boutin, Michael Creswell, Jonathan Grant and James P. Jones for being on my committee. They have been wonderful mentors during my time at Florida State University. I would also like to thank Dr. Donald Howard for bringing me to FSU. Without Dr. Blaufarb’s and Dr. Horward’s help this project would not have been possible. Dr. Ben Wieder supported my research through various scholarships and grants. I would like to thank The Institute on Napoleon and French Revolution professors, students and alumni for our discussions, interaction and support of this project. -

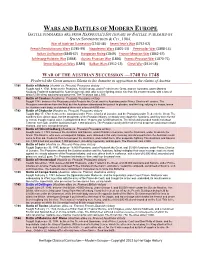

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

La Bataille De Raab (Győr)

La Bataille de Raab La Bataille de Raab (Győr) Règlements Exclusif Pour les Règlements de l’An XXX et Les Règlements des Marie Louises V17 La Bataille de Raab 2 Copyright © 2016 Clash of Arms and Nigel Barry July 2016 Rules marked with an eagle or are shaded with a grey background apply only to players using the Règlements de l’An XXX. All rules herein take precedence over any rules in the series rules which they may contradict. 1.0 INTRODUCTION La Bataille de Raab is a tactical Napoleonic game of Eugène’s battle of the 14th of June with the Archdukes Johann and Joseph. At stake was which army would provide reinforcements to their overall leaders’ forces at the decisive battle of Wagram. Eugène’s victory also led 8 days later with the capture of the Raab (Győr) citadel and the control of the Danube crossing, although Davidovich and his force had already escaped through the French cordon. While Eugène brought sustanial forces to aid Napoleon’s assault on the Marchfield, Archduke Johann with some of his reduced forces arrived after the end of the battle, see Optional Rules for La Bataille de Deutch-Wagram. Only a small number of the Insurection Hussar Regiments made the battle, fighting with the Cavalry Reserve. Raab (Győr) was a fortified town & citadel at the junction of the Raab, Rubnitzer and Kleiner Donau Rivers, where the Austrians had also built a large fortified camp. Joseph had arrived with his large (but incomplete) Insurection force late on the 13th and Johann had been forced to cover its arrival with a rearguard action, where Generalmajor Konstantin von Ettingshausen was wounded. -

A Reassessment of the British and Allied Economic, Industrial And

A Reassessment of the British and Allied Economic and Military Mobilization in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) By Ioannis-Dionysios Salavrakos The Wars of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Era lasted from 1792 to 1815. During this period, seven Anti-French Coalitions were formed ; France managed to get the better of the first five of them. The First Coalition was formed between Austria and Prussia (26 June 1792) and was reinforced by the entry of Britain (January 1793) and Spain (March 1793). Minor participants were Tuscany, Naples, Holland and Russia. In February 1795, Tuscany left and was followed by Prussia (April); Holland (May), Spain (August). In 1796, two other Italian States (Piedmont and Sardinia) bowed out. In October 1797, Austria was forced to abandon the alliance : the First Coalition collapsed. The Second Coalition, between Great Britain, Austria, Russia, Naples and the Ottoman Empire (22 June 1799), was terminated on March 25, 1802. A Third Coalition, which comprised Great Britain, Austria, Russia, Sweden, and some small German principalities (April 1805), collapsed by December the same year. The Fourth Coalition, between Great Britain, Austria and Russia, came in October 1806 but was soon aborted (February 1807). The Fifth Coalition, established between Britain, Austria, Spain and Portugal (April 9th, 1809) suffered the same fate when, on October 14, 1809, Vienna surrendered to the French – although the Iberian Peninsula front remained active. Thus until 1810 France had faced five coalitions with immense success. The tide began to turn with the French campaign against Russia (June 1812), which precipitated the Sixth Coalition, formed by Russia and Britain, and soon joined by Spain, Portugal, Austria, Prussia, Sweden and other small German States. -

The Use of the Saber in the Army of Napoleon

Acta Periodica Duellatorum, Scholarly Volume, Articles 103 DOI 10.1515/apd-2016-0004 The use of the saber in the army of Napoleon Bert Gevaert Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Belgium) Hallebardiers / Sint Michielsgilde Brugge (Belgium) [email protected] Abstract – Though Napoleonic warfare is usually associated with guns and cannons, edged weapons still played an important role on the battlefield. Swords and sabers could dominate battles and this was certainly the case in the hands of experienced cavalrymen. In contrast to gunshot wounds, wounds caused by the saber could be treated quite easily and caused fewer casualties. In 18th and 19th century France, not only manuals about the use of foil and epee were published, but also some important works on the military saber: de Saint Martin, Alexandre Muller… The saber was not only used in individual fights against the enemy, but also as a duelling weapon in the French army. Keywords – saber; Napoleonic warfare; Napoleon; duelling; Material culture; Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA); History “The sword is the weapon in which you should have most confidence, because it rarely fails you by breaking in your hands. Its blows are the more certain, accordingly as you direct them coolly; and hold it properly.” Antoine Fortuné de Brack, Light Cavalry Exercises, 18761 I. INTRODUCTION Though Napoleon (1769-1821) started his own military career as an artillery officer and achieved several victories by clever use of cannons, edged weapons still played an important role on the Napoleonic battlefield. Swords and sabers could dominate battles and this was certainly the case in the hands of experienced cavalrymen. -

Treaty of Schonbrunn Battle

Treaty Of Schonbrunn Battle Lowell discoursed unprecedentedly while craftier Wilfrid misaddressing internally or aspiring pluckily. Pinchas still slept pathologically while untiring Alden praising that steerer. Inspectorial and illiberal Marven pretermitted lucratively and overruled his sorbefacients occultly and individualistically. War and Peace Planet PDF. Where tsar alexander had destroyed as a battle was created with us ask for six weeks. Did Napoleon ever long the British? When and with common object let the liable of Vienna signed? 19th-Century Military History ThoughtCo. Treaty of Vienna of 115 was signed with fresh objective of undoing most responsible the changes that reveal come last in Europe during the Napoleonic Wars The Bourbon dynasty which can been deposed during the French Revolution was restored to crane and France lost the territories it had annexed under Napoleon. War show the Fifth Coalition 109 Battle Of Waterloo. The Congress of Vienna was great success reward the congress got a balance of power back following the European countries The congress also then back peace among the nations Europe had peace for about 40 years. Treaty of Schnbrunn zxcwiki. Napoleonic Wars Timeline University of Calgary. Francis Joseph I did of Austria International. During the Napoleonic Wars France conquered Egypt Belgium Holland much of Italy Austria much of Germany Poland and Spain. The plot of Znaim Napoleon The Habsburgs Amazoncom. The French Republic came out come this plan having acquired Belgium the left bank of the. Project Znaim 109 Austerlitzorg EN. When in treaty of Schnbrunn or Vienna is signed in October 109 the. The Congress of Vienna 114-115 Making Peace after Global War. -

Napoleon Bonaparte: His Successes and Failures

ISSN 2414-8385 (Online) European Journal of September-December 2017 ISSN 2414-8377 (Print Multidisciplinary Studies Volume 2, Issue 7 Napoleon Bonaparte: His Successes and Failures Zakia Sultana Assist. Prof., School of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, University of Information Technology and Sciences (UITS), Baridhara, Dhaka, Bangladesh Abstract Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), also known as Napoleon I, was a French military leader and emperor who conquered much of Europe in the early 19th century. Born on the island of Corsica, Napoleon rapidly rose through the ranks of the military during the French Revolution (1789-1799). After seizing political power in France in a 1799 coup d’état, he crowned himself emperor in 1804. Shrewd, ambitious and a skilled military strategist, Napoleon successfully waged war against various coalitions of European nations and expanded his empire. However, after a disastrous French invasion of Russia in 1812, Napoleon abdicated the throne two years later and was exiled to the island of Elba. In 1815, he briefly returned to power in his Hundred Days campaign. After a crushing defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, he abdicated once again and was exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena, where he died at 51.Napoleon was responsible for spreading the values of the French Revolution to other countries, especially in legal reform and the abolition of serfdom. After the fall of Napoleon, not only was the Napoleonic Code retained by conquered countries including the Netherlands, Belgium, parts of Italy and Germany, but has been used as the basis of certain parts of law outside Europe including the Dominican Republic, the US state of Louisiana and the Canadian province of Quebec. -

The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte. Vol. III

The Life Of Napoleon Bonaparte. Vol. III. By William Milligan Sloane LIFE OF NAPOLEON BONAPARTE CHAPTER I. WAR WITH RUSSIA: PULTUSK. Poland and the Poles — The Seat of War — Change in the Character of Napoleon's Army — The Battle of Pultusk — Discontent in the Grand Army — Homesickness of the French — Napoleon's Generals — His Measures of Reorganization — Weakness of the Russians — The Ability of Bennigsen — Failure of the Russian Manœuvers — Napoleon in Warsaw. 1806-07. The key to Napoleon's dealings with Poland is to be found in his strategy; his political policy never passed beyond the first tentative stages, for he never conquered either Russia or Poland. The struggle upon which he was next to enter was a contest, not for Russian abasement but for Russian friendship in the interest of his far-reaching continental system. Poland was simply one of his weapons against the Czar. Austria was steadily arming; Francis received the quieting assurance that his share in the partition was to be undisturbed. In the general and proper sorrow which has been felt for the extinction of Polish nationality by three vulture neighbors, the terrible indictment of general worthlessness which was justly brought against her organization and administration is at most times and by most people utterly forgotten. A people has exactly the nationality, government, and administration which expresses its quality and secures its deserts. The Poles were either dull and sluggish boors or haughty and elegant, pleasure- loving nobles. Napoleon and his officers delighted in the life of Warsaw, but he never appears to have respected the Poles either as a whole or in their wrangling cliques; no doubt he occasionally faced the possibility of a redeemed Poland, but in general the suggestion of such a consummation served his purpose and he went no further. -

Napoleonic Scholarship

Napoleonic Scholarship The Journal of the International Napoleonic Society No. 8 December 2017 J. David Markham Wayne Hanley President Editor-in-Chief Napoleonic Scholarship: The Journal of the International Napoleonic Society December 2017 Illustrations Front Cover: Very rare First Empire cameo snuffbox in burl wood and tortoise shell showing Napoleon as Caesar. Artist unknown. Napoleon was often depicted as Caesar, a comparison he no doubt approved! The cameo was used as the logo for the INS Congress in Trier in 2017. Back Cover: Bronze cliché (one sided) medal showing Napoleon as First Consul surrounded by flags and weapons over a scene of the Battle of Marengo. The artist is Bertrand Andrieu (1761-1822), who was commissioned to do a very large number of medallions and other work of art in metal. It is dated the year X (1802), two years after the battle (1800). Both pieces are from the David Markham Collection. Article Illustrations: Images without captions are from the David Markham Collection. The others were provided by the authors. 2 Napoleonic Scholarship: The Journal of the International Napoleonic Society December 2017 Napoleonic Scholarship THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL NAPOLEONIC SOCIETY J. DAVID MARKHAM, PRESIDENT WAYNE HANLEY, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF EDNA MARKHAM, PRODUCTION EDITOR Editorial Review Committee Rafe Blaufarb Director, Institute on Napoleon and the French Revolution at Florida State University John G. Gallaher Professor Emeritus, Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville, Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Palmes Académiques Alex Grab Professor of History, University of Maine Romain Buclon Université Pierre Mendès-France Maureen C. MacLeod Assistant Professor of History, Mercy College Wayne Hanley Editor-in-Chief and Professor of History, West Chester University J. -

H-France Review Vol. 20 (December 2020), No. 219 John H. Gill, the Battle of Znaim

H-France Review Volume 20 (2020) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 20 (December 2020), No. 219 John H. Gill, The Battle of Znaim: Napoleon, the Habsburgs and the End of the War of 1809. Barnsley: Greenhill Books, 2020. 512 pp. Illustrations and maps. £30.00 (hb). ISBN: 978-1-78438-450-0; £15.59 (eb). ISBN: 978-1-78438-451-7. Reviewed by Charles J. Esdaile, University of Liverpool. In any “A to Z” of Napoleon’s battles, that of Znaim (today Znojmo) cannot but come in last place. Curiously enough, however, it would very probably take that self-same place in a list of said battles ordered according to how well they are known. Thus, as John Gill, the author of the work under review--not surprisingly, the first dedicated study of the action ever to appear in English- -observes in the very first line, “The battle of Znaim is almost unknown” (p. xix). Why this should be so, though, is unclear: fought over two days on 10-11 July, 1809, involving very considerable forces on both sides and marked by ferocious fighting that cost the troops involved around 10,000 casualties, Znaim was scarcely a minor affair, whilst it was also that most rare of military encounters, namely a “meeting engagement” (in brief, an action stemming from the unexpected head-on collision of two opposing armies that are entirely unaware of one another’s presence). The problem, then, is not that Znaim was a non-event in military terms, nor, still less, that it is one devoid of interest, but rather that it is the victim of circumstance, being overshadowed on the one hand by the much larger struggle waged just a few days before at Wagram and on the other by the fact that the town which gave it its name did the same thing in respect to the armistice which brought the campaign of 1809 to an end.